Climate Cycle: Riding for Change

Peter Foot put out a call to see if anyone would join him on a 1,000 km ride between Melbourne and Canberra to raise awareness about climate change, and several people showed up. They pedaled along Australia’s backroads, talking openly with the people they met along the way and asking them to make pledges of action. Here’s their story…

PUBLISHED Apr 5, 2019

Words and photos by Peter Foot

On a sunny morning in October, a 27-year-old man walked down the sands of Middle Park Beach in Melbourne with a glass jar in his hand. He filmed himself as he did so, talking to the camera.

“I’m here to collect a symbolic amount of seawater to deliver to parliament.” The lapping of waves fills the spaces between his words. “It seems like they’ve forgotten that there is ocean surrounding us, that so many people are in danger of inundation from sea-level rise.” He squats down and then holds the jar to the camera, now with briney water and some sand in the bottom. “So this is a bit of a wake up call. A reminder that they’re not so isolated up on that hill, and that they can’t keep ignoring the science and the danger, and Australia’s responsibility.”

That was the official start of our ‘non-charity’ bike ride to Canberra.

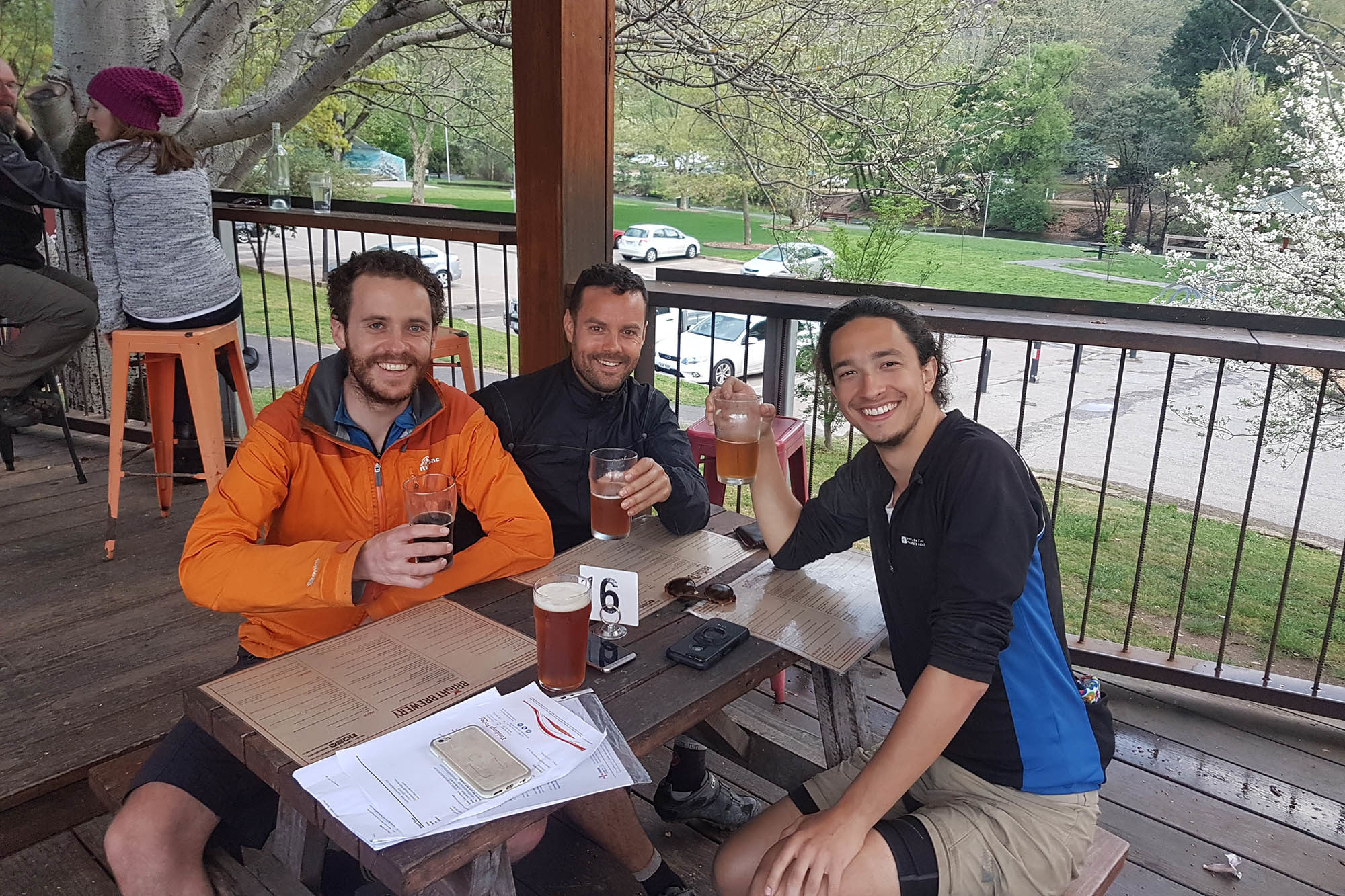

But it started, really, as many things do, over a frothy. A few frothies. A month earlier, I was having a beer with this man at a brewery on my street, a converted warehouse where fine ales and gentrification flowed from the taps. We sat at a wooden table, on wooden benches. Bar chatter surged between the high walls.

For the last hour we had been talking fast, thinking hard, throwing ideas back and forward and throwing beers down, and creating lists of things to do. It’s a strange feeling when an idea you had a decade ago—a weird idea that you never really pursued—starts to take form in front of your eyes. It took someone who shared the vision. Nathan was willing to put in some effort to organise this thing and that’s what convinced me, that after all those years fermenting, the time had come.

We talked and plotted until we were quite drunk and my head was a scramble of intersecting tasks possibilities, and alcohol, and I realised that my mental powers were drained. I emptied my glass and set it on the table.

“Let’s leave it there for now,” I said. Sometimes people use the word mane flippantly, but Nathan had a proper one. A head of long, dark, curly, voluminous hair that seemed to hark back to primeval humanity. I couldn’t help but notice it one more time as I rose from my bench. We walked outside and we shook hands and Nathan went to unlock his bike.

As I turned to walk down the street I pointed at him. “I’ll…” I tried to remember what the next thing was that I was supposed to do in our plan, but nothing came.

“Things will happen,” I said, still pointing, and staggered into the night.

Changing the system

I originally conceived of it as a sort of pilgrimage. Part protest, part adventure, part celebration of spirit. But most of all, a cry from a generation that’s being screwed over. A journey to the heart of political power in this country to deliver a message: you have betrayed us. You are unfit for power. We are coming for you.

The “non-charity” part was something that came to me more recently. You see, I’ve developed a problem with charity rides—even charity more generally. Let’s just say someone is riding to raise money for homelessness services. Good on them. It’s a cause they no doubt believe in. That money may have a tangible, positive effect on a number of people’s lives. But it begs the question: why are 100,000 people in Australia homeless in the first place? How many charity rides will you have to do to ultimately solve the problem? I can’t help but think that that well-intentioned money is doing little more than papering over the yawning cracks through which 100,000 people have fallen.

My aim here is not to disparage anyone who has raised money for, or donated to a charitable cause. Donations have their place; certain things simply need to be funded. My point is that sometimes we give money without really thinking about it, as a way to ease our guilt, and in doing so we avoid dealing with the structural problems that underlie the issue.

So on this ride we did not ask people to give us money. They probably needed it to keep up with their rising bills, their rent, their home loan repayments, their student debt, because unless, in our society, you already have a lot of capital, you too are being screwed. Asking people to donate to something that should be properly funded by government, using the taxes of those who can afford it, is only going to perpetuate that system.

What we asked for instead—if people wanted to support our cause—was pledges of action. We created a list of suggested actions that were aimed at creating structural change, from writing to or meeting your MP to divesting your superannuation to engaging in protest and civil disobedience to simply reading a book that talked about some aspect of the climate crisis and how to solve it. Our aim was to get people to engage with the issue rather than simply throw money at it.

Also, we deliberately avoided advice like: change your light globes, drive less, eat less meat. Yes, these things help, but they will not, on their own, solve the problem. We have been told too often to fight climate change within the individualist paradigm of neoliberal capitalism. For 40 years we have failed to see that neoliberal capitalism itself is the problem. We have lost sight of our collective power and the possibility of transformative change.

To the Hills

On a Saturday morning, about a month after our ‘planning meeting,’ I walked my bike into Federation Square in central Melbourne. While I stood in the sun and the heat built up on me, people trickled in. Family, friends, family of friends and friends of family, and a random guy called Jaron who found out about the ride on Facebook. We’d only chatted once online, briefly, a few days before. His decision to join seemed pretty spur of the moment. He introduced himself to the group.

“How far do you plan to go?” Nathan’s dad asked him.

“All the way to Canberra, hopefully,” Jaron said. “See how I go.”

“I borrowed all my camping gear from a mate of mine.” He seemed pretty breezy about the whole thing.

We’ll see how you go, I thought to myself. It wasn’t that I doubted his ability; his legs looked pretty strong. It was that getting people to commit to things—much smaller things, usually—is often a draining, tedious struggle. Yet here was a person who had sprung up out of the ground like a mushroom and was saying he wanted to ride 1000km with me. It was just a bit hard to believe.

More people converged on our little gathering on the sandstone blocks of the square, including Nathan, who had just returned from the beach with the jar of water. And as I rubbed sunscreen into my arms and got ready to ready to roll out, my mate Kimbo turned up, with full panniers and a sleeping roll occy-strapped to his bike. He looked vaguely confused, like someone who’s just risen from bed.

“You’re here! I thought you weren’t coming.”

He waved a hand dismissively. “I woke up this morning and thought, fuck it, why not.”

And so we were four.

Drawing on my experience of cycling Victoria’s back blocks, I had developed a route that would take in some of the most scenic areas and roads between the two cities. I chose minor roads where possible—many of them gravel—to minimise traffic, and I incorporated four separate rail trails. I made it challenging enough for experienced cyclists, but not so hard as to scare off a novice. Apart from the political stuff, I was excited to take on 1000km of what I knew would be top notch cycling.

By day’s end we had cycled 106km and we were getting the first inkling that this might kind of work. We were gelling as a team of four, and developing an easy and respectful rapport. We’d had a bunch of conversations already, with people who were curious about what we were doing, which allowed us to spread the word about our cause. And we had received our first free meal. Nathan’s cousin happened to be camping at the same place as us on the first night, and handed over plates and containers of delicious leftovers from his family’s dinner.

After three days we had made it to Mansfield in central Victoria. Kimbo had left us due to a sore knee. The riding had been challenging but incredibly scenic. The route was exceeding even my expectations.

“I just got off the phone to Gentle Annie,” Jaron said the next morning. “I’ve booked us into the man cave.”

There was rain forecast, and rather than pitch our tents in the wet, we had decided to book a caravan in Whitfield, 60km away. I didn’t know much about the road ahead. It was merely the simplest way to get over to the King Valley. We left at 2:00 in the afternoon and rode straight into a headwind. Showers blew over. The rolling farm country was bleak but theatrical in the weather, shape shifting in the swirling grey.

After a long, straight climb we turned onto a quiet ribbon of bitumen that threaded its way through forest. Soon we began to push into fog. Then the fog thickened up, like gravy in a frypan, and kept thickening to the point where I turned my lights on and almost had to slow down.

It was peaceful up here. The air was wet and unruffled. There was only our own breath, and the clicking of our chains and our tyres on the blacktop, and the chirping of wrens in the trees. Wattles grew at the roadside, in flower, splashes of yellow in the austere grey.

We rode on for a couple of hours, the road rising and falling, and curving around. Sometimes it was tight and narrow, and closed in by vegetation. Other times it was open and straight, vanishing into the mist. I settled into a slow cadence, a dreamy flowing rhythm.

We passed a transmission tower, and the fog suddenly lifted. Then the land dropped away on one side, and across a deep valley rose a mountain flank covered in forest lush as emotion. I squeezed on the brakes and came to a stop.

“Holy crap.”

Columns of sunlight hit the mountain side, and mist rose from the trees. I pulled out my camera and snapped a couple.

“This is like Jurassic Park,” Jaron said as he rolled past.

Not far on, we passed paddocks and letterboxes, and driveways with weatherboards behind them. Then the road started to slope down properly. I zipped up my jacket and hooked my hands into the drops. I could sense that this was the last downhill. The big one.

The wind flapped at my jacket sleeves and built up in my ears. It was just steep enough to go fast, but not so steep that I had to brake. I eased the bike around corner after corner, revelling in the speed, the sense of free miles, the perfect tarmac.

Then I swung around a right hander and I was on the side of a mountain. Just like that. Over the guardrail the ground disappeared, and I was hundreds of metres up, and lurid green paddocks roiled away, and more mountains rose up in the distance, covered in forest, dark and green and haunted by more mist, and more clouds around their shoulders. I was still going fast, still railing corners, and now with a sense of drama and grandeur that had come on so swiftly and powerfully that I shook my head and cackled like a mad cockatoo.

Then I plunged back into the bush. I went faster again. The beautiful corners kept coming. Measure, brake, lean, line the next one up. I laughed again and a smile cracked my lips. The air became fat and muggy with warmth. And finally I was spat out onto the valley floor, but even then it wasn’t over. The road kept sloping down between fields of grass, as if it were playing an encore, and I hardly took a pedal stroke until I pulled up outside the general store, where I stood over my bike, unmoving.

Jaron rolled in a couple of minutes later. He smiled wryly and shook his head. We knew we couldn’t really say anything to do justice to it.

“That was just…”

“Oh my god.”

More head shaking.

“That was one of the best roads… and I’ve done a lot of riding.”

“I nearly teared up coming down that.”

Then Nathan joined us, also smiling in that not-quite-there kind of way, and we walked over to the pub and ordered a beer.

The man cave was aptly named. An old caravan inside a shed, with a couch, sink, microwave, and fridge. It was ad hoc and comfortable. It was just the kind of place you could imagine middle aged blokes sitting around sinking Beam and complaining about their wives.

And he was garnering a following. People were tuning in. The pledges of action were rolling in too, a growing list of comments on a blog page of my website. It was rough and imperfect, a bit like the man cave, but it was working.

People we met on the road were responding as well. When we told Russel and Dea, the proprietors of Gentle Annie, about our cause, decided not to charge us for the man cave. Then they called up the local pub and put a hundred bucks on a tab for us for dinner, which w only discovered when we went to pay. We were actually shocked. It was much more generosity than we felt we deserved, or could even accept (we did, in the end). We were set for the next night as well. The manager of the brewery in Bright, our destination the next day, had heard about us and offered to put us up when we came through.

“This climate change thing isn’t so bad,” Jaron said as he sipped on a local red at the pub.

We slept well in the man cave and woke to another moody, misty day. As we left Whitfield behind and climbed the gravel slopes of Rose River Road, I could feel this thing coalescing. I had put an idea out there, without a lot of planning, and no sophisticated publicity campaign, and it was taking on a life of its own. I had merely pushed it down the hill. As we pedalled we were already talking about next year—how to make it bigger, how to make it better—and our voices were swallowed up by the quietness of the bush.

It’s apathy, not denial, that’s killing the planet

A few days before we started in Federation Square, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) unleashed its latest climate change report upon the world. It was easily the most strongly worded to date, and its message was clear: 2°C of warming may well be catastrophic, and to keep it to 1.5°C we need to act radically, and fast.

People react differently when they face news like this. Some will be spurred into action. Some will deny the problem altogether, and call it a green-left conspiracy. Others will soberly digest the facts, understand in their waters that this is a grave threat to our existence, then continue living much as they did before. Perhaps they’ll change their light globes or something. This is the most common reaction. And it is this reaction, not denial, that is the biggest threat to the planet.

Despite the noise that deniers make in the media and politics, polling indicates that they are relatively few in number. Most people accept that the planet is warming, that it is caused by human activity, and that we should do something about it, even if it comes at some cost. Yes, it’s true!

Some people had reservations. A guy in a pub in Corryong asked us if we wanted to shut down his industry. He was concerned about what these changes might mean for him and his family, an understandable reaction given our government’s utter failure to communicate what a proper response to climate change might mean, or spell out any sort of plan for the people these changes will affect. Yet despite this he was happy to talk to us, to engage constructively with some folk from the city.

This was about the most challenging conversation we had. The more common reaction was outright support, such as that offered by Russell and Dea, or the articles that appeared in local newspapers. I suspect that one of the reasons people were so enthusiastic about our ride is that we were tapping into a quiet undercurrent of alarm. That in many communities a veil of silence hangs over climate change. That it’s not brought up in polite company because people don’t know how, or they don’t want to be that ‘crazy lefty,’ or it’s all too much. So when we rolled through town, out and proud, as it were, people suddenly felt less alone.

We need to break this silence, if we are to have a chance of surviving. It is the first step. We need to be talking honestly, even bluntly, about the dire situation we are in, and we need to do this en masse. We would all feel less alone if we did this, and perhaps emboldened, inspired to demand change. If we can find our common purpose, as intelligent, moral people, the deniers will be easily overwhelmed. As long as we stay quiet, we will sleep walk into oblivion.

The Roof of Australia

I went out in the morning to collect the tent fly. It was hanging between two trees, drying in the sun. I was on the edge of a plain, a carpet of perfectly green grass, and all around were the humps of kangaroos bending down to graze. Joeys also flopped around, coming to terms with their gangliness, and above it all stood the main range of the Snowy Mountains, white domes shimmering in the sun.

I felt that I was seeing of one of nature’s great spectacles. In fact, I wasn’t just seeing it, but it was stealing into me, making me bigger than I was. Mostly we feel around in the darkness, but from time to time we brush against the great web of life, and it’s impossible not to feel it, somewhere in your bones.

A handful of galahs in their dirty pink flew into a tree near me, scuffling and squawking about something. I walked over slowly to have a closer look, and they leapt off into another tree. When did we decide that we needed a new phone every year? Or that we should settle on Mars? When did we decide that this wasn’t enough?

Almost immediately after setting off, the road angled up, a single lane of black top through the forest. It was steep but it was consistent. I fell into a rhythm and grinded. We had a lot of climbing in our legs from yesterday, and I could feel the chutzpah fading. Half way up, we stopped at a picnic area and we all sat around, heavy and dazed. I lay on my back on a wooden table, staring at the gum leaves moving in the breeze, and the blue sky beyond, and I ate half a packet of mint slices. We were only a few days from the end now. Nathan had managed to wrangle more time off work, so he was in it till the finish. Jaron was still going strong as well.

We kept on through the morning until we were snatching glimpses of other mountains through the trees, and the air started getting sharper, and the trees smaller, and then they were gone altogether, and the ground was covered in alpine grass, and patches of snow lined the road. And all of a sudden we were at Dead Horse Gap, the high point of the whole ride.

A valley opened up on the other side, wide and dramatic, with the road cut into the right slope, and on the left a line of peaks with the snow still thick on them. Mount Kosciuszko was up there somewhere; the roof of Australia. We stopped and collapsed onto the grass, and breathed in the moment, and the crystalline air. The others hopped back on and rolled down the hill. Within a few seconds they were tiny figures on wheels, racing down the valley and away. I lingered for a few moments, then I too rolled away.

To the End

The next day we rode through officially drought declared country. You could see why. It was the lushest time of the year, yet the paddocks only managed a weak patina of green, and the ground underfoot crackled with the dry.

Late in the afternoon the wide open paddocks turned into dry eucalypt forest, then bucolic countryside. The colours were like from an artist’s easel. Dusty greens, shades of brown, the ghost grey of tree trunks. We rode slowly, just kicking the pedals over. We were absorbed by the scenery and swimming in fatigue. We crossed into Namadgi National Park and the Australian Capital Territory, and a while later we came to a hut.

“This is it,” I said as soon as I saw it. “We’re staying here tonight.”

In an open field stood an old squatter’s hut hewn from grey logs and rusted iron. A soft breeze ruffled my shirt sleeve, and the pale sun cast our shadows long. A rough path through the grass invited me to go and have a look, as if I were in a fairytale.

I walked down and unlatched the door. It swung open with a groan. Inside, it was dark and spare. There was a table in the corner and a hearth at one end and gaps in the floorboards. I walked across and opened the door on the other side of the room. I stepped out onto a verandah, walked to the edge, then slouched against one of the posts and took a deep, relaxing breath. This is a bloody fairytale.

We ate dinner sitting on our bums on the verandah there, eating rolls and cheese and dip and local smoked trout. I chewed slowly as the light faded and the air turned bitter, and I stared out over the field and to the wooded slopes beyond. What is it worth, all this?

And that was it, basically. The next day we rode into Canberra and came to a stop outside parliament house. My dad had been harassing politicians over the phone and via email, and a few of them came out to meet us and help spread our message of an emergency response to climate change. We filmed Nathan while he said a few words and tipped the seawater onto the forecourt. And after that we went to the pub.

Did our little expedition avert a climate catastrophe? In and of itself, of course not. Did it make a difference? Of course it did. Was it enough? Nobody can answer that. We all must hold this uncertainty within us, during this coming age of crisis. We must live with this jarring dichotomy in our minds. We all need to do our bit. Yet we must also tend to our lives, our souls, and savour the livid tastes of being. Perhaps, with this bike ride, we did a little of both.

You can find a guide to Peter’s Melbourne to Canberra route over on his site, Adventure Cycling Victoria.

About Peter Foot

Peter Foot is a freelance writer and bike shop employee who lives in Melbourne, Australia. For over a decade he has been exploring his home state of Victoria on two wheels, as well as other parts of Australia. Since 2016 he has documented his travels on his website, AdventureCyclingVictoria.com.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.