Reflections on the Arizona Trail: Profound Joy and Big Questions

Nicolaus Hawbaker rode the length of the Arizona Trail for his first bikepacking trip, and found himself asking big questions about wilderness stewardship as he pedaled through its picturesque landscapes. In this short essay, he reflects on the lasting impression his time on the trail left on him, and offers some thoughts on the importance of preserving natural beauty…

PUBLISHED Jan 16, 2019

Words and photos by Nicolaus Hawbaker

Countless hours of research and a year of training still didn’t prepare me for the profound impact the Arizona Trail would have on me. Not only did the trail showcase the diversity of Arizona’s unique wilderness, but it also unexpectedly raised philosophical questions about Arizona’s wilderness stewardship and provoked personal lifestyle changes.

I was setting off on my first bikepacking trip, and my spirit was bursting with anticipation of the adventures to come – and a bit of apprehension. I chose the Arizona National Scenic Trail, an 800-mile non-motorized path through Arizona’s valleys, deserts, canyons, mountains, forests, and historic communities.

After leaving Tucson at 3:00 am, my wife dropped me off at the US – Mexico border, just west of the Huachuca Mountains. Soon, the desert sun would rapidly warm the San Rafael Valley. Timing my traverse of Arizona was tricky. I had to balance the heat of the southern Sonoran Desert with the late season snowstorms of northern Arizona. Was I adequately prepared for the elements, wildlife encounters, and navigational obstacles? There was no time to dwell. It was 6:30 am., the sun had been up for over an hour, and I had 60 miles to put in before the day’s end. Armed with an audio copy of the finest works of Edward Abbey for entertainment, I set off on my single speed mountain bike.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I’d never before heard of some of the canyons, rivers, and mountain ranges I crossed out there. Discovering the Mazatzal Mountains, Gila River Canyons, and Mogollon Rim was truly amazing. While riding along the Gila River Canyon, temperatures rose above 100 degrees by 9:00 am. I survived by sleeping in the foul smelling Gila River, attempting to avoid heat stroke under the shade of a cottonwood, cattle feces floating all around me. The pungent stench of the Gila River still lingers in my nostrils.

Shortly after leaving the river, with 40 miles left to reach Superior, I ran out of food. I became further discouraged by news of the 16,000-acre Tinder forest fire burning in northern Arizona that forced a mandatory detour. Rising global temperatures and the driest fall/winter season in recent memory were even threatening to shut down the Coconino and Kaibab National Forests. My hopes of completing the Arizona Trail were fading. Thankfully, a late-season snowstorm quenched the parched forest floor, allowing me to continue my journey.

My discussions with hikers from other countries led me to think more about what I’d seen along the trail, particularly the plethora of cattle. As a longtime Arizona resident, I’ve grown accustomed to seeing cattle grazing in national forests and on state land. A Canadian hiker asked me why Arizona allows cattle to graze on, erode, and tarnish this world class wilderness. I couldn’t answer her.

There was an article circulating among hikers, published by Backpacker magazine, about Rep. Martha McSally hiking the Arizona Trail. Surely, there would be more resistance to the Arizona Cattlemen’s Association lobby after one of our congressional representatives experienced the wonder of the AZT and witnessed the same wilderness degradation that I did. Unfortunately, it seems that cattle have more right to our public lands than humans. This past summer, as national forests all over the western U.S. shut down to visitors due to unprecedented forest fire risk, ranchers and their livestock were among those granted exception to the restrictions. And despite the characterization of wilderness in The Wilderness Act of 1964, “…where man himself is a visitor who does not remain,” the cattle are allowed to remain.

My experience on the AZT prompted me to ponder the role of ranching in our society. I had a lot of time for deep thought as I carried my bike, strapped to my back for 23 miles across – and one vertical mile up and down – the Grand Canyon section of the Arizona Trail. I still haven’t found a reasonable explanation for the contradiction that cattle are allowed to graze in our National Parks, but if my bike tires touch the Grand Canyon’s dirt, I’ll be steeply fined and my bike confiscated.

In the final section of the Arizona Trial, as I descended off the Kaibab Plateau toward the red sandstone monuments of Utah, I wondered what would happen if everyone were to experience the Arizona National Scenic Trail. My experience gave me an even greater appreciation for the incredibly diverse landscapes in our state, and forced me to reconsider the role of cattle on our public lands. I urge other Arizonans to enjoy this world-class trail, and to see how doing so might inform your perspective.

As society continues its inevitable progress and wilderness becomes increasingly sparse, we must fight to preserve the natural beauty we’ve been entrusted with. If more hikers and cyclists, politicians and constituents, omnivores and vegetarians, conservatives and liberals experience our national treasure, perhaps we can take the words of President Lyndon B. Johnson more seriously, “If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt, we must leave them something more than the miracles of technology. We must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning, not just after we got through with it.”

The Arizona Trail (AZT)

- Distance: 739 mi (1,189 km)

- Days to Complete: 14-21

- % Unpaved: ~90%

- % Singletrack: ~65%

- Total Ascent: 64,961′ (19,800 m)

- High Point: 9,007′ (2,745 m)

- Route Guide: View here

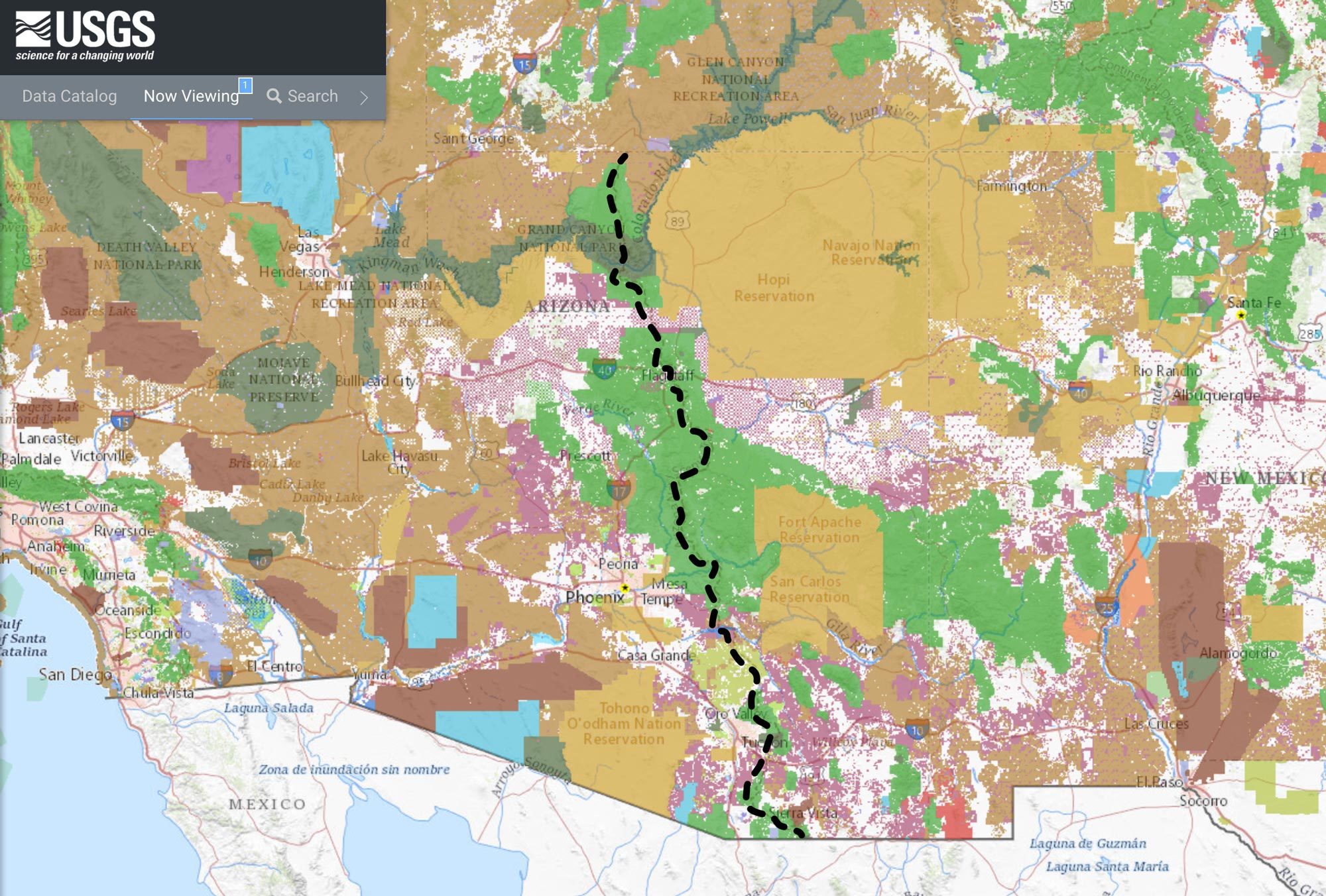

85% of the Arizona Trail is on federal lands. It crosses the Coronado, Tonto, Coconino, and Kaibab National Forests, three National Parks, two Bureau of Land Management areas, one State Park, and Arizona State Trust lands. Explore the USGS Protected Areas Database map to see where these lands start and stop.

Cattle grazing isn’t all that’s threatening the lands on which the AZT sits. Current legislation and public land transfer is also a major concern in Arizona, and the west as a whole. Learn more about our public lands and the importance of protecting them by visiting REI’s Guide to Understanding Public Land. You can also keep track of various legislative issues that affect public lands, track new legislation, sign this petition, and call or write your senators and representatives by texting your zip code to 520-200-2223 (or congress switchboard: 202-224-3121) to get connected.

About Nicolaus Hawbaker

Nicolaus Hawbaker is an avid cyclist and outdoor enthusiast. He grew up in Indiana and began cycling after resettling in Arizona during high school. He now resides in Flagstaff, Arizona, and enjoys mountain biking and skiing there. He works as an Emergency Medicine Physician. The Arizona Trail was his first bikepacking adventure and it left him eager to explore more of the country this way.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.