El Silencio: Ponderings From The Pampa

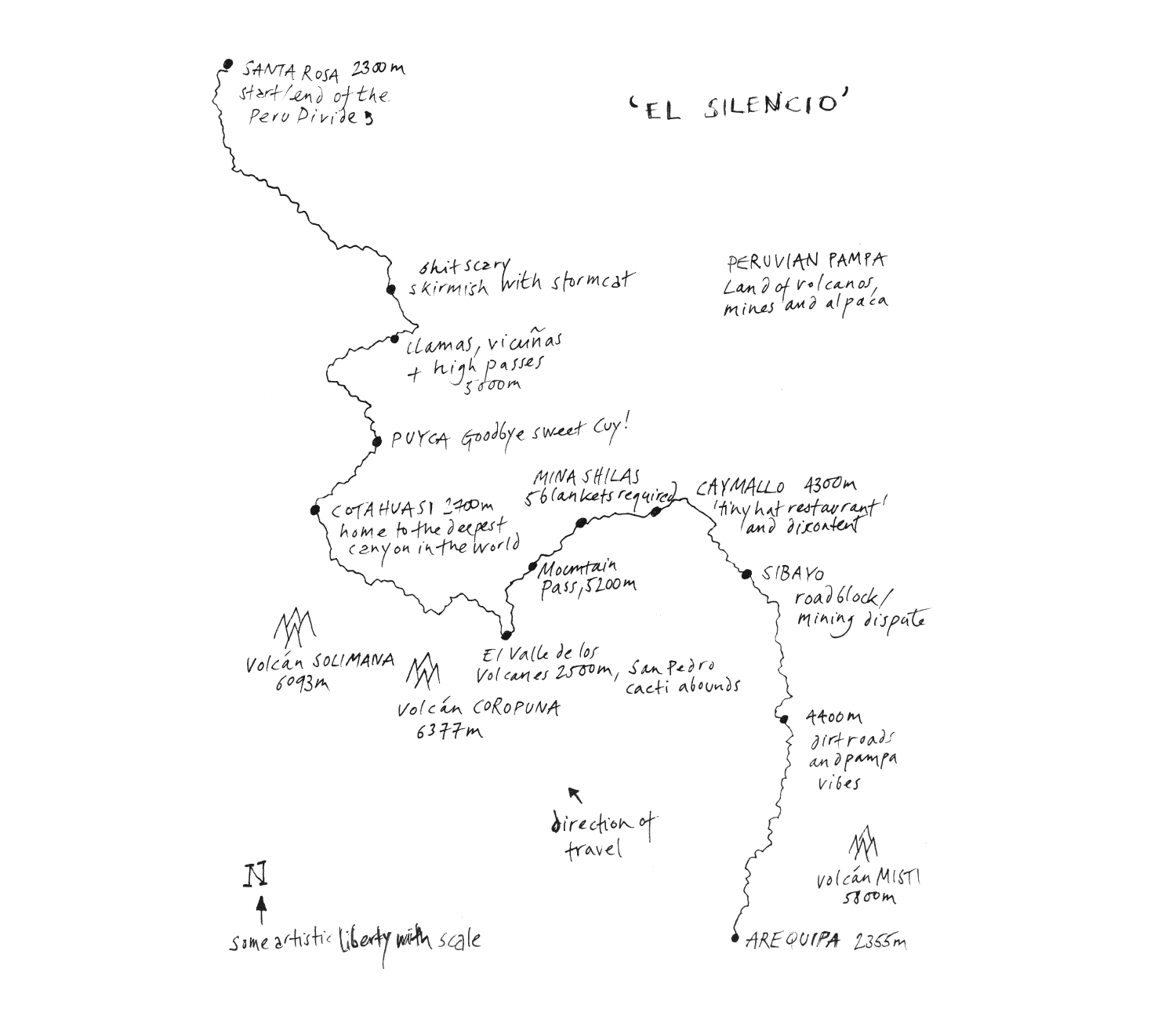

Peruvians call it El Silencio. The highest reaches of the country’s Andean mountains is a quiet, startlingly beautiful, and unrelenting harsh pocket of the world, interlinked by rugged mining roads and faint alpaca trails. But despite its challenges, there’s nowhere quite like it to ride your bicycle, promises Cass Gilbert, as he ponders the cathartic quality of the solo tour and learns to savour its solitude.

It can be lonely up on the Andean pampa. But it’s a good kind of lonely. The quiet, cathartic, meditative kind. Peruvians, a noisy people by nature, call it El Silencio – the Silence. And not without reason. All I can hear is my laboured breath, the wind whistling through my cycling cap, and the soothing scrunch of bicycle tires on dirt.

I think back to when I last talked to anyone. Here, only the smallest of communities scratch out a living. Hardy llama and alpaca shepherds tend their animals, flocks and herds speckled across the plateaux or clinging to the slopes of steep-sided valleys, their sense attuned to where valuable water flows. When I pass these men, I call out ‘Buenas dias!’ It’s as much to break the silence as it is to create a connection. A fleeting connection at that but an important one, for me at least. And perhaps it is for them too, isolated as they are, because they wave back and smile broadly, watching me ride by until an errant alpaca demands their attention. The houses they live in are simple, homemade, mud wall structures, marked by thin plumes of smoke where fires are stoked within. It’s a warmth I know I’ll covet, once the sun has slipped behind the folds of the Andes and a biting coldness envelops the land, seeking to pervade my very being. Come nightfall, I’ll be wrapping up in every single one of the layers I own and soon be sipping cups of coca leaf tea.

Indeed, El Silencio is a formidable, harsh environment that can challenge every last sinew of your being. Everyday events include hours of hairpin climbs, a relentlessly strong, lip-cracking sunshine, and needle-like hailstorms that can leave me red and raw. I can only imagine how hard it is to be brought up here and the endless struggle of subsisting in such an unrelenting, unforgiving landscape. Yet as much of an outsider as I am, it’s also a land I can’t help but feel drawn to, even if my indulgent explorations comes with the luxurious veneer of the passing tourist.

Since leaving town behind, early this morning, I haven’t dropped below 4500m in elevation. Up on the pampa, lingering at such extreme altitudes isn’t even unusual; at one point, I even hovered at a similar height for several days on end, yoyo-ing up and down mountain passes that regularly breached the hallowed 5000m marker – a mighty 16400ft. Vehicles are few and far between, though occasionally I cross paths with a motorbike; a balaclava, padded onesie, and Wellington boots the typical attire of its rider.

It’s early afternoon when I pause for a snack beside a stack of apachetas, the traditional stone cairns that mark offerings to the gods. To the Incas, springs, rocks, mountains, lakes and caves all had their own spiritual power. Although this mighty civilisation’s prominence proved short-lived – it’s zenith lasting but a hundred years – vestiges remain evident across the length of the Andes. Just the other day, descending a mountain pass, I stopped to talk to a group of young men headed for a nearby mine, who had paused on their own journey to toast these stacks of rocks with thimbles of liquor. Together we drank, discussing life and celebrating it, sprinkling a few drops from each shot onto the ground. For Pachamama, mother earth, I’m told. “We’re descendants of the Incas” they said, “so we keep this tradition alive.”

Musings on mining

In fact, mines and their impact have been a recurring thread throughout this three-week ride, which began in the city of Arequipa and will lead me to Ayacucho, a market town in the central cordillera. Rich in gold, silver, and copper, large-scale mines have become the lifeblood of a modern, developing Peru, whether it be in Pachamama’s interests or not. They’re also the reason why so many of the dirt roads I delight in exploring even exist, an unfortunate irony I can’t deny. Everywhere I look, the earth is streaked with minerals; rich veins of deposits that look otherworldly in the midday light. It’s both astonishingly beautiful and unbelievably sad. Sad, because these deposits are the reason an ever-growing number of unsightly gouges pock the landscape, the calling cards of multinationals that race to strip the land of her precious metals, before closing up shop and moving on.

Inevitably, the act of riding across such vast, open spaces steers me towards self-reflection. In my mind, I’m solving the Earth’s puzzles, even if I know that at times I’m as much a part of the problem as anyone else. Why is it that we have so little regard for nurturing this planet of ours? Why is the world of consumption so linear, when it needs to be circular? I consider the lure of profit and the relentless need for economic growth, hiding such environmental and social costs in plain sight. At least I know that in this regard, the humble bicycle has it right.

I dwell. I ponder. Solo riding is meditative and I’ve always felt it acts as a pathway to a clarity of sorts. Out there alone, I contemplate my actions and clear my mind, like a monk shuffling around an infinite and silent monastery. With a couple of weeks of cogitation to my name, I’ve come to the conclusion that all the underbellies in our society – landfills, mines, and the like, the ones that bicycle touring so ably reveals – need to be seen in person, a forced reminder of the impact that we create through the decisions we make. I wonder idly if there should even be school trips, just as there are to museums. After all, they seem just as important to our future as an understanding of the past. And because it’s harder to ignore such inconvenient truths when you’ve seen them for yourself.

I ride on through this rugged mining district, deep in thought. My protracted ruminations feel justified, because the impact has reached a point in Peru where even the miners themselves comment on the contaminacion del agua – the contamination of groundwater – caused by their workplace. Twice on this trip I’ve been delayed by strikes manned by angry, troubled communities, tired of the destruction that’s left behind, and the money that isn’t. In one town these demonstrations lasted over a week. I won’t deny it was both nervewracking and stirring to see people take matters into their own hands. All the shops were closed, public transport had ground to a standstill, and villagers had formed impromptu barricades to stop vehicles from passing through, jabbing fingers into chests and arguing forcefully with those who were made to stop, disgruntled by the damage caused so many mining trucks. I’d ridden the same roads that very day, bouncing around from one pothole to the next. They were indeed feo, as people say here. Ugly. Not that I could claim the same of the surrounding views. But sensibly, epic panoramas were held in less regard than the comfort of a bus ride to the weekend market.

By chance, I even checked into a small hospedaje – a small hotel – to rest on the day this discontent seemed at its most vocal. A throng of unhappy people had taken to the street to voice their feelings and shake their fists, as is the way in South America. I was pointed to the one restaurant that was allowed to remain open during the strike; an enclave of warmth, it was heaving with demonstrators hungry after a day manning the barriers outside. I must have looked a sight. Despite the frigid temperatures, I was still wearing my riding shorts, an act of complete lunacy to mountain dwelling Peruvians. “He’ll catch a cold,” I heard one old lady mutter disapprovingly. It was clear that I was foolish sight, not an endearing one. “His tiny hat looks like a baby’s,” another chuckled, more sympathetically this time, pointing at the woollen cycling cap I wore with such pride. The owner slapped down a caldo before me, a chicken soup that came complete with authentic, outstretched claw. This was followed shortly after by a piece of grizzled, unidentifiable meat, a small mountain of rice, and a delicious tea made from a local mountain herb. I struck up a conversation with a group of young guys at my table, learning about their woes and misgivings. And in turn, they quizzed me too. “Are you travelling alone? Aren’t you afraid to be up in El Silencio by yourself? There are dangerous animals and ghosts up there…” But before I could explain that this comforter of silence was exactly what I sought, we were hustled out into the coldness once more, as another round of diners waited to take their seats.

But it would be wrong of me not to share stories of the welcome I received in the mines themselves. Mina Shilas is perched at an oxygen-depleted 4800m in altitude. It’s owned by Buenaventura, one of the largest producers of gold and silver in Peru. Arriving in the late afternoon, it would have been a push to make over the pass that day. So instead I was given my own room, complete with 5 heavy blankets that crushed what remaining breath I had in me, a hearty dinner, and a massive breakfast. We ate together at a communal table while I fielded various questions. We took photos of each other. We swapped Facebook accounts. The following morning, the miners shook my hand and wished me well on my journey.

On that day, I left the miners to their earth-digging machines and crested the highest pass on the trip, before spiralling downwards once more, down and down and down… past a vast lake in which people fished for trout and flowers blossomed, past a village store that sold little more than Inca Cola and local moonshine. On that day, the landscape morphed once again in an interplanetary way; ancient, bulbous mosses coating the land gave way to cacti sprouting from cracks in volcanic boulders, leaving me to marvel once more at the delicate and diverse beauty of Peru.

Are you for real?

As is typical with almost any bike tour, so many memories are compressed into just a few weeks and a thousand kilometres of riding. Memories that never fail to steer my mind to more positive thoughts should I find them erring towards worldly sadness. The kindness of those I’ve met, one that always feels especially open to the solo tourer. The conversations I’ve shared. The simple gifts I’ve received. My favourite? A handful of piping hot, freshly boiled potatoes, their skins still encrusted with dirt, proffered from the shoulder bag of an elderly man who waved me down for a chat. For what is travel but tangible proof that everyone in the world can connect, no matter where they may come from and what their background may be… if we only make the effort to put ourselves out there. Such travels can serve as a valuable reminder that each connection, as small as it may seem, has the power to create a lasting impression and ripple ever outwards. Impressions that, in their own way, have the ability to change the way we perceive the world, and help cultivate a respect for all those who we share it with.

Of the many, a few stand out, one of which was more of a canine kind. On this occasion, I was stuck behind a traffic jam of torros bravos – fighting bulls – when a small black dog started to follow me, trotting alongside my bike as if it was something he’d done every day of his life. As the dirt road I was following wound its way higher to crest a high pass, he persisted, shortcutting the switchbacks, waiting patiently for me to catch up each time. I nicknamed him Cuy – the Peruvian for a guinea pig, a local culinary delicacy.

The hours went by and later I reached a village. When I checked into a guesthouse for the night and wouldn’t let him share my room, he slunk off to find his own abode out of the rain. Come nightfall Cuy tracked me down again, curling up around my feet on the second floor of a barebones restaurant, where I was joined by a government worker from Arequipa, visiting the local health centre, and a man sent in with a digger to clear a landslide.

Cuy’s presence didn’t go unnoticed. But rather than kicking him out, the owners of the restaurant insisted I take leftover chicken scraps for what they assumed to be ‘my dog’. When I explained that I didn’t want to encourage him to follow me further, their refute was simple. “Well, he must think you need company.” Come morning, a shopkeeper advised me to sneak away quietly down a dirt road before the dog saw me. But Cuy caught me in the act and came bounding eagerly over once more, ears pricked in merry delight at such an enjoyable game. It didn’t help that everyone had by now assumed he was undoubtedly my dog, to the point that they pressed yet more bags of leftovers into my hands “for our journey over the mountains.” Nor did it help he was incredibly good natured and cute. After I explained that where I was headed was no place for a little fellow like him, I asked a curious bypasser – for by now a small crowd had gathered to offer advice – to hold the dog back. As much as it broke my heart to say goodbye to my temporary travel companion, I left to ride on alone once more, with some sorrow.

Another day on the ourskirts of a village, a young woman and her son hailed me down to help load their donkeys with bagfuls of grit. When she found out I’d never loaded up a donkey with supplies before, she enjoyed a good laugh. “Don’t you have donkeys where you’re from?” she asked somewhat incredulously, her subtext evident: Are you for real? What kind of a world to do you come from where you don’t even know how to load up a donkey? One of the bags was particularly back-breaking to lift. “That one’s for the macho,” she said, pointing to a waist height donkey that was only marginally larger than the others. I was a quick lean and by the third animal, I had the knots and loops figured out. “Come find us if when you’re next passing through”, she said, “and we’ll make you some food.” Then she and her son headed home, loaded donkeys tottering behind, before the afternoon rains began.

The Storm Cat

I’d come to fear those afternoon rains. Or certainly, respect them. The monsoon season had hit the country especially hard that year, destroying bridges, causing landslides, and generally wreaking havoc all along Peru’s Pacific coast. But here in the high Andes, the weather had been on my side. In fact, I’d already dodged a storm that morning, an ink blot that seeped across the sky. Thankfully it was a mere skirmish, the mountains bore the brunt of the attack and cleared the way for blue skies before me.On another occasion, I wasn’t so lucky. It was only after I’d found a perfect ledge to pitch my tent, wild horses and vicuñas as my neighbours – the wilder, more wiry cousins of the domesticated llama – that I spied the storm on the other side of the valley. Lurking, brooding and foreboding. I considered packing up and finding a more sheltered nook but couldn’t summon the energy. So instead, as a dined on quinoa, I watched it from the corner of my eye, as it crept its way ever closer. I tried to feel confident and nonchalant, but concern was quickly getting the better of me.

Cue ever louder, deeper, primaeval rumbles of thunder and ever more alarming shards of lightning… In the darkness of a tent, everything is amplified and so very dramatic. Soon, rain was drumming hard and loud above me and an almighty wind was pressing the tent’s slender walls inwards, like some powerful, magical force trying to touch me. All of a sudden, my world was lit up bright as claps of thunder deafened my ears. In my mind’s eye, I imagined the storm looking straight down upon me, the blip of my tent in the enormity of the pampa, pondering my inconsequential existence. Would my epitaph read: Here lies the gravestone of Cass Gilbert, struck by lighting in the Peruvian mountains because he couldn’t be bothered to move? Although I’d taken extra care to pitch the tent securely, piling rocks high like apachetas, I quickly packed everything delicate that I owned in waterproof bags, in case my home was ripped from above me. My heart was beating fast.

Oh… for the sense of relief that came, finally, when the storm cat relinquished its hold on me and moved its attention elsewhere. Like a manic professor whose experiment had careered out of control but had ultimately been successful, I couldn’t help but laugh… and then, weirdly refreshed, I allowed myself to sleep especially soundly.

And so my mind returns to where I am and the cycle of my time on the pampa repeats itself again. Soon, I’ll need to scope out a place to camp, for once the sun drops behind the panorama of volcanos, coldness will quickly follow. It’s always a delicate balance. Spot a perfect campsite too early and the temptation to keep riding is strong. Leave it too late, and I’ll consider pushing on to the next town, lured by the challenge of covering more distance in a day and the promise of a meal and some company. This evening, I’ll do my best to hold myself back. After all, what’s the rush? Just look at where I am.

Slowing down. This is why I choose a bicycle as my form of exploration. Ironically, it’s sometimes harder to let go of goals then it is to set them. I have to remind myself: what am I achieving in crunching miles, when I can cocoon myself in my tent, appreciating the good fortune that’s brought me here, right now. I’m learning to savour this solitude and recognise the value it brings. Yes, the water in my bottles might freeze and I’ll struggle to light my stove. But despite its undeniable hardships, I wouldn’t have it any other way. I’ve never been more aware of my own existence than here; reminded by my laboured breath, my ageing, sun-wrinkled skin, the people I meet, the llamas that watch me, and the heartbreaking beauty of the mountains that surround me.