Pinion Gearbox Review: A True Bike Transmission!

Share This

When the Pinion gearbox launched in 2006, the German company took a massive risk by abandoning the typical derailleur/cassette-style drivetrain in favor of the same technology used in automobile transmissions. Find our full Pinion gearbox review here with insight into this system and our findings on the 12-speed and 9-speed C-line after bikepacking and trail riding with them for several months. Plus, learn how the Pinion’s gearing compares to other drivetrains and much more…

Words by Logan Watts, photos and video by Neil Beltchenko

It’s pretty clear what the most heated battle in the mountain bike industry is now. The drivetrain—or transmission, as SRAM is now calling it—is on a quickly evolving trajectory as the two leading titans attempt to outdo each other year after year, all in hopes of capturing more of the market share and perfecting the derailleur-based drivetrain. It’s a fight that’s been building up over the last few years as 1×12 has taken a firm foothold and SRAM and Shimano leap-frogged one another with 50, then 51, and now 52-tooth cassette cogs.

However, no matter how much they progress technically, even the most advanced derailleur drivetrains face the same three shortcomings: 1. Excessive cog and cassette wear due to variable chainline and jumps between gears; 2. Need for frequent maintenance and tuning; and 3. The fact that a rear derailleur (also known as the hang down in some circles) will always be one of the most damage-prone and vulnerable parts of a modern mountain bike. Aside from spokes and the chain, it’s the most susceptible to mud, dirt, and debris. Let’s face it, it’s a fragile mechanical device that’s essentially hanging off the side of your bike, ready to be ripped off at will by the next rock or tree branch on the trail. Even more, with cassette rings becoming larger and pushing over 52 teeth, this puts the derailleur lower and in an even more vulnerable position. As bikepackers, we’re particularly attuned to all of these potential points of wear and failure.

As the back-and-forth drivetrain battle ensues, several lesser-known internally geared systems have been lurking in the shadows. All of them virtually eliminate all three of the issues mentioned above. The most well-known is the Rohloff Speedhub. But, as mountain bikers are quick to point a gloved finger at, the heavy rear Rohloff internally geared hub throws off a bike’s center of gravity. This is where the idea of a gearbox comes in. It centralizes the drivetrain at the bottom bracket position, which is technically the heart of a bike’s weight center.

Theoretically, gearboxes have the potential to overtake the entire industry based on their ability to partially solve the weight distribution issue and upend the common woes of a traditional drivetrain. I stress theoretically, but gearboxes do make a lot of sense. They greatly reduce chain and cog wear by removing variable chainline, they stay in tune by design, and they eliminate the most fragile appendage on a mountain bike—the rear derailleur. Plus, with minimal annual maintenance, they can potentially last a lifetime. This especially resonates in the age of the latest and greatest $500+ replacement cassettes. They also move the weight to the bike’s center, in between the wheels. Because of this, gearbox bikes aren’t like most other bikes. The bike is built around the gearbox, so instead of the typical bottom bracket shell, bottom bracket, and cranks, transmissions like the Pinion gearbox reviewed here have a one-piece design where the frame is specifically designed for the gearbox to bolt onto.

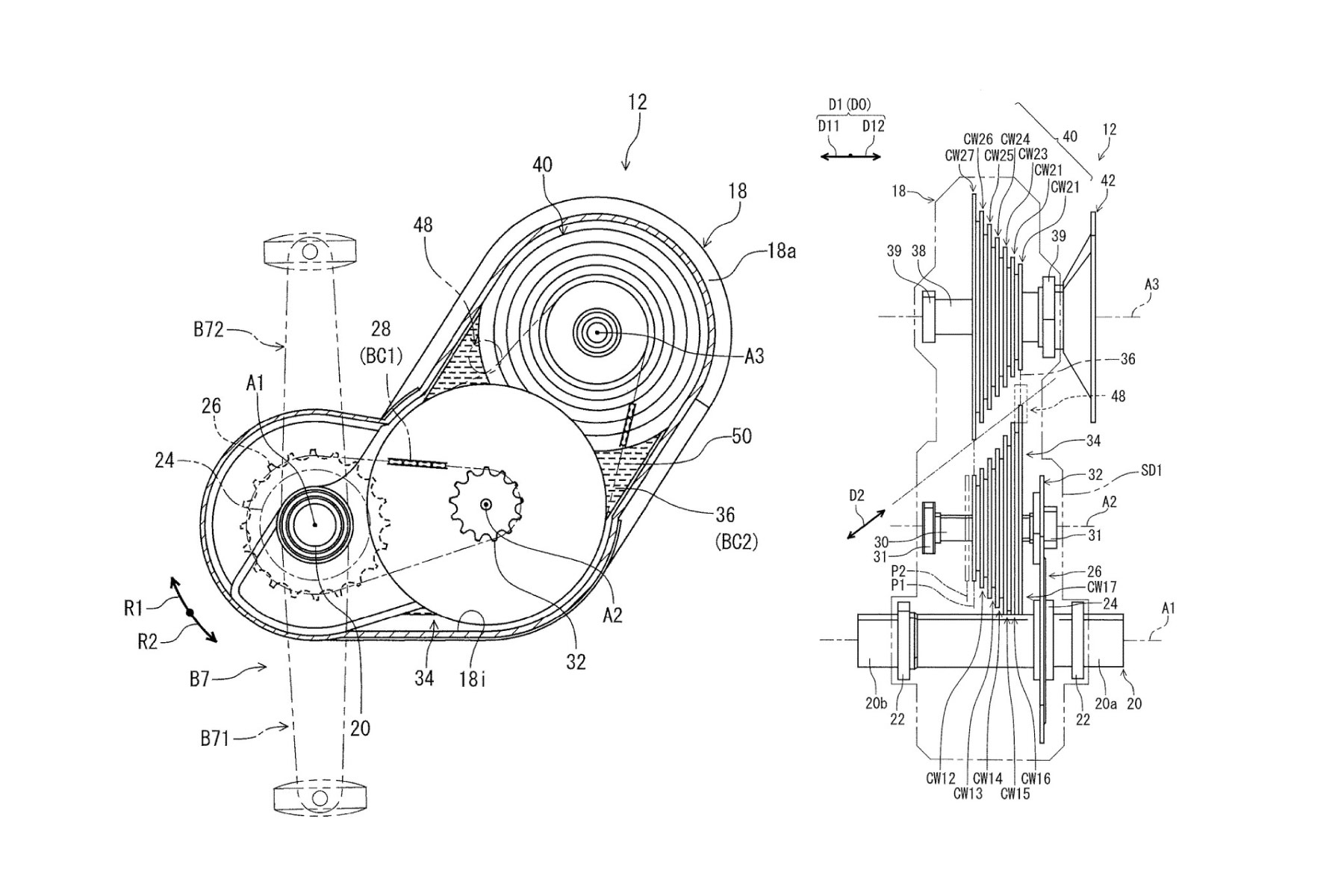

For this reason, among others, the gearbox has its own set of hurdles, and it would take quite an upheaval for it to gain mainstream success in the mountain biking world. Even so, the most promising contender is Pinion, a small German company founded by Christoph Lermen and Michael Schmitz, two former Porsche engineers. And, if their resumés aren’t enough to solidify Pinion’s made-in-Germany cachet, the mind-bending inner workings of their fully sealed 12-speed Pinion C1.12 and P1.12 gearboxes should do it. To summarize very loosely, the P and C1.12 are truly transmissions. Like Pinion’s other models, the oil-bath shell houses a sprocket array and a camshaft that shifts through 12 unique consecutive positions and aligns the two sprocket groups in a dizzying display of engineering magic. It works extremely well, which is probably why companies such as Colorado-based Viral Bikes are choosing to build their bikes solely around the Pinion system.

For this review, Neil tried the C1.12 and the C1.9xr gearboxes on the Viral Derive. Watch below, then scroll down for more information on how the gearing compares to other drivetrains, along with my writeup of the P1.12 from my time with it back in 2017.

Pinion Gearbox P Series vs. C Series

Pinion offers two types of gearboxes, the P-line and the C-line. The P-line comes in 18 and 12-speed versions and is housed in a machined aluminum case. The lighter C-line comes in 12, 9, or 6-speed varieties and has the same general inner workings, although Pinion claims they’re 33% lighter due to the more compact Magnesium case.

As mentioned, Neil tested the C-line in the 9-speed C1.9 that came on the Viral Derive. Pinon also sent the 12-speed for him to compare. Oddly, I tested the P1.12 on the Viral Skeptic several years ago, so we’ve covered most of them. We’ll dig into the weights, prices, and gearing in the next sections.

Pinion Gearbox Ranges Compared

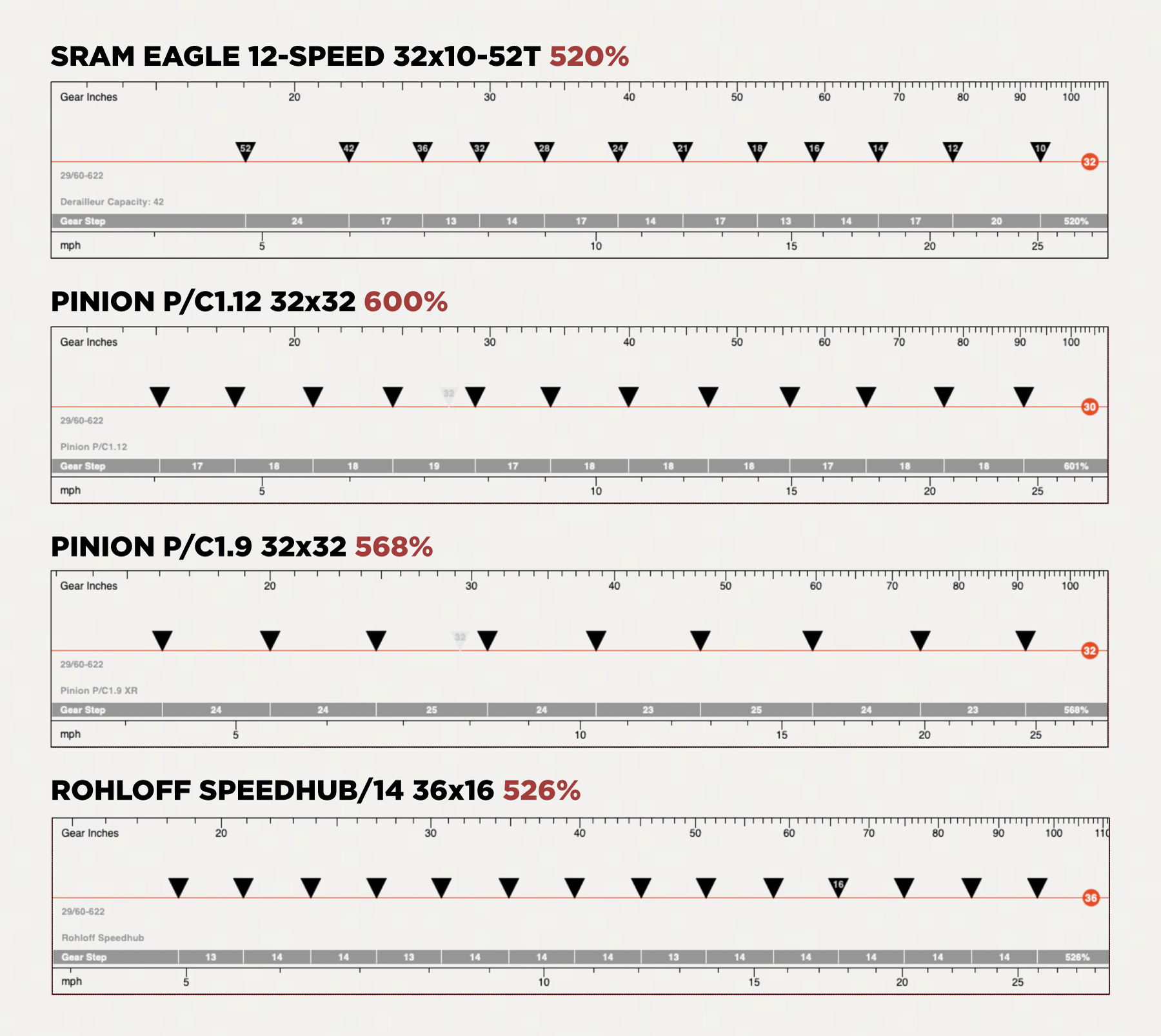

The biggest difference between the Pinion gearbox and a traditional derailleur drivetrain is the jump between shifts. With a cassette, the amount of gear change in a shift is based on the number of teeth specced on each cog by the manufacturer. Higher (smaller) gears are more governed by what’s available. For example. When you go from the smallest 10-tooth cog to the next cog on a typical SRAM Eagle cassette, you have to go to either an 11-tooth cog, which would only be a 10% bump, or a 12-tooth cog, which is a 20% bump. There is no such thing as an 11.5-tooth cog for a perfect 15% bump. So, you are limited to gear jumps on a cassette, and the jump can be pretty drastic. But, with the Pinion gearbox, you are getting the same jump between gears with every shift. The 12-speed Pinion has a 17.7% jump across all gears, and the 9-speed C1.9 has 24.3% between gears.

Neil and I both tested the 12-speed Pinion gearboxes, which are probably the most common. The 12 gears of the Pinion P and C1.12 deliver a massive 600% gear range. Compared to the 526% gear range in a Rohloff Speedhub, the 520% range of the SRAM Eagle 1×12, 491% from a 2×10 (36/24 chainset/11-36t cassette), and the average 435% range of a 1×11 setup, the C1.12 is unrivaled. It’s noticibly impressive while riding, too, and almost hard to use the whole range on many rides, although it’s nice to have the extra granny gear while bikepacking. Even the C1.9 has a 568% range, which is higher than the other drivetrains mentioned. For reference, here’s a chart showing how the 9- and 12-speed Pinions compare to a SRAM Eagle drivetrain and the 14-speed Rohloff Speedhub.

Pinion Gearbox Weights and Prices

As utopian as a gearbox drivetrain may sound, the Pinion still faces two big hurdles in the greater market: weight and price. At 2,350 grams for the gearbox alone, Pinion’s P1.12 is still considerably heavier than the Eagle X01 12-speed drivetrain—or even the Rohloff. And that doesn’t factor in the crank arms, cogs, chain/belt, or the added weight the mounting plate creates over a traditional BB shell. These bits add up to at least an additional 600 grams. To compare, the Eagle X01 group weighs about 1,500 grams with the chain and cranks included. So, comparatively, the Pinion P1.12 almost doubles the weight of the 12-speed Eagle drivetrain. However, the Pinion C1.12 shaves off about 200 grams using a magnesium alloy casing. Here’s a list of actual weights. Note that we didn’t include shifters or cables—only the gearbox plus crank arms for Pinion units—and derailleur/cassette/crankset (w/32T ring) for the Eagle drivetrain. The Rohloff weight is just the internally-geared hub, so you’d need to factor in a crankset weight for comparison.

- Pinion P1.12 2,887 grams

- Pinion C1.9 2,596 grams

- Pinion C1.12 2,693 grams

- Rohloff Speedhub/14 1,845 grams

- SRAM Eagle GX 1,388 grams

The big takeaway here is that the weight of the C1.12 is nearly double that of the Eagle GX components, and that doesn’t include the additional weight that comes from the plate assembly on the frame, which is likely heavier than a bottom bracket shell. That’s a hard pill for the industry to swallow, although we all know that weight doesn’t matter in the long run, particularly for loaded bikepacking.

The price of the Pinion gearbox is complicated, no matter the model. First, it’s tricky to simply buy one. And even if you could, buying a box without a frame would be useless. As such, Pinion gearboxes are mainly sold through bike manufacturers and frame builders. In 2017, Steve Domahidy pointed out, “…for me, the Pinion represents about $2,000 of the retail price of the $4,999 frame kit [for the previous Viral Skeptic]. This includes the gearbox, CNC cranks (which are more expensive), shifter, all of the mounting hardware, a spacer kit for the single speed rear cog to fit on a full-size cassette body, the lock ring tool, and one oil change.” He also explained that the titanium bridge that the Pinion mounts to is an expensive part of the frame. It is a single-cast piece of titanium with CNC finishing. Compared to other builders making steel or titanium Pinion frames, “[They] are using a plate and then welding the mounting holes onto that, which to me [for accuracy] is not the right way to do it.”

Maintenance (or lack thereof)

Like a Rohloff, one of the biggest draws to the Pinion system is the minimal maintenance required. Pinion recommends a simple oil change in the gearbox every 10,000 kilometers (6,200 miles), or each year, whichever comes first. Additionally, it uses a belt drive, and the cogs used for belts last much longer than a traditional chain drivetrain. They also don’t require any lube and work well in adverse conditions. Simply put, the sealed unit means a much more reliable drivetrain. Plus, there is no ongoing tuning that needs to happen that requires tinkering with high or low limits, B-tension, or a bent derailleur hanger.

Pinion Gearbox Review (P1.12)

To add to Neil’s findings, here’s the crux of my review from my time with the P1.12 Pinion gearbox in 2017 on the Viral Skeptic.

Similar to the C1.12 that Neil reviewed above, the P1.12 shifts between gears at an increase/decrease percentage of 17.7%. Those are dramatic gaps between gears compared to the 13.6% of a Rohloff or most derailleur drivetrains. This took a minute to get used to, especially skipping two or three at a time to jump down to lower gears for quick upcoming steep climbs. All of a sudden, my legs would start spinning like the Roadrunner. After getting used to the step percentage, it was no problem, and I quite liked the more consistent and dramatic gaps. Some derailleur gaps are inconsistent, especially when considering big 50 and 52-tooth cassette expansions and extra-large low gears.

As Neil mentioned, one of the biggest complaints folks have about the Pinion is that you can’t shift under load. Indeed, it takes getting used to when coming from a derailleur drivetrain. But, considering that I have a bit of experience with a Rohloff and that I don’t even shift under load with a derailleur system, it wasn’t too much of an adjustment period for me. In fact, I immediately loved the way the Pinion shifted and thought it was impressively snappy. I found it notably smoother and quicker than the Rohloff, although it worked similarly with the twist shifter. Adding to its pleasant usability was the Industry Nine Torch hub specced on the Viral, which gave it a quick audible bzzt to accent the shift time.

Mechanical Efficiency

All this leads to the elephant in the room. How much drag or friction is created with all these gears in an oil bath? Looking into the mechanical engineering of it, while the gears on the Pinion are spinning, only two are engaged at any given moment. Pinion claims this reduces friction when compared to other sealed gearboxes. It’s noticeable, but both Neil and I agreed that it’s negligible and something you get used to pretty quickly.

Although I didn’t have the opportunity to ride both back to back, the Pinion P1.12 seemed a little more efficient and less draggy than the Rohloff, where multiple gears are constantly in contact to produce the gear ratio. However, as a others pointed out, there have been studies about the mechanical efficiency of the Pinion Gearbox, particularly the P1.18. Looking closer at this study conducted by Andreas Oehler, the numbers in the mechanical efficiency chart tell a different story. The baseline singlespeed appears to average around 97%, with the second contender being the Rohloff at ~94% (which is surprising). The Pinion P1.18 looks to have about a 91%-ish efficiency rating. There is no graph data for a typical derailleur drivetrain, but considering that the singlespeed got a 97, with only two points of cog contact and a straight chainline in play, a two-pulley derailleur drivetrain with a varying chainline would have to be significantly less. Also note that this study was performed with the Pinion P1.18, which I’m guessing is less efficient than the 12 or 9-speed C1.12 or C1.9, by nature.

Durability

As for durability, although both of us put quite a few miles on our respective Pinion gearboxes, neither of us tested the Pinion enough to figure out how long it lasts. That would require a few years and a boatload of miles. Pinion suggests that gearboxes can have a lifetime of more than 100,000 kilometers if they’re maintained regularly. Also, Pinion offers a three-year manufacturer warranty on each gearbox.

If you’re considering the Pinion Gearbox, or weighing it out as an option, consider these general pros and cons that we found while testing the P/C1.12 and C1.9 units.

Pros

- Low maintenance (relatively maintenance-free) and very durable

- Eliminates the need to replace high-wear parts, like cassettes and chains

- Centers drivetrain weight at lower-center of bike’s bottom bracket area

- The Pinion gearbox shifts faster than traditional derailleur drivetrains

- The ability to shift multiple gears at once, even when stopped

- Equal jumps between gears is predictable

- C1.12 and P1.12 have a super wide gear range

Cons

- Can’t shift under load

- Heavy compared to other drivetrains

- Requires a Pinion-specific frame that can be expensive

- Some folks won’t like the grip shifter—although Pinion is purportedly working on an electronic shift system

- Slow engagement with play in gears

- Lower mechanical efficiency than cassette/derailleur-based drivetrains

Parting Thoughts

The Pinion Gearbox has a lot going for it. It’s incredibly reliable, eliminates the need to replace components regularly, and it minimizes the risk of anything breaking, such as a derailleur or hanger. It also has an unmatched gear range. So, why isn’t it on more bikes? The non-traditional Pinion-specific frame is probably the biggest stumbling block that Pinion is facing. Its unique bolt-on plate configuration where the bottom bracket would be on normal bikes, makes the frame beholden to Pinion for the remainder of its days, unlike other bikes that can be disassembled and rebuilt with other parts. However, I think that could be overlooked if the industry was on board with the gearbox. The added weight is probably the bigger setback. Despite centering the weight low, where it should be, the Pinion C1.12 is still more than 1.3 kilograms (2.8 pounds) heavier than a typical Eagle GX drivetrain, and the C1.9 isn’t far off.

Still, there are currently 100+ brands that build bikes around the Pinion, and while they may not be taking over the world, it does seem that more and more bike brands—particularly ones hinging their bets on adventure—are considering the gearbox. And with its excellent shifting functionality, long lifespan, and trouble-free platform, the gearbox seems like a logical step in the right direction. It’s a great option for anyone setting out on a long bikepacking trip, folks looking for more gear range, or people who want a maintenance-free system that doesn’t require the constant need to replace parts. Perhaps brands are waiting for the perfect model that comes in a lighter weight?

As Viral founder Steve Domahidy put it back in 2017, “Nowhere in current mountain bike technology did we demand perfection before acceptance, so it’s a little bit hypocritical to do that with the gearbox. Among others, disc brakes and both front and rear suspension all went through serious growing pains but are now considered necessary for mountain bikes. The first Manitou suspension fork was little more than aluminum legs sliding on aluminum stanchions with some elastomer bumpers in between, and the naysayers came out in droves claiming it was too heavy, too expensive, and too complicated. The Pinion is much further along in the development cycle than the original Manitou fork was to modern-day suspension.”

Related Content

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.