“Superstition is the poetry of life.” —Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

With travel information available everywhere all the time, guidebooks have become rather useless. Perhaps the only reason to buy a Lonely Planet anymore is to reference the customs and traditions section and learn about a place’s unique eccentricities—information to be used as an abridged visitors’ code of conduct. The widespread don’t shake hands with your left isn’t instinctual. Neither is the uniquely Turkish don’t chew gum at night. So, it’s a good practice to get a sense of these things prior to visiting a place. Kyrgyzstan has a few curious customs of its own, some of which can’t be found in guidebooks and a few that are, apparently, hard to adopt.

We didn’t have to worry about fitting in with the locals and their traditions for most of our trip. Joe, Joel, Lucas, and I were outside in remote mountains the majority of the time. We were alone among ourselves, save the omnipresent horses and perhaps the spying eyes of imperceptible snow leopards. Only once, mid-trip, in the town of Naryn, did we sleep at a guesthouse, and a gaggle of rowdy Russians there made us more or less invisible. Every other night, we were cocooned in the solitude of our tents.

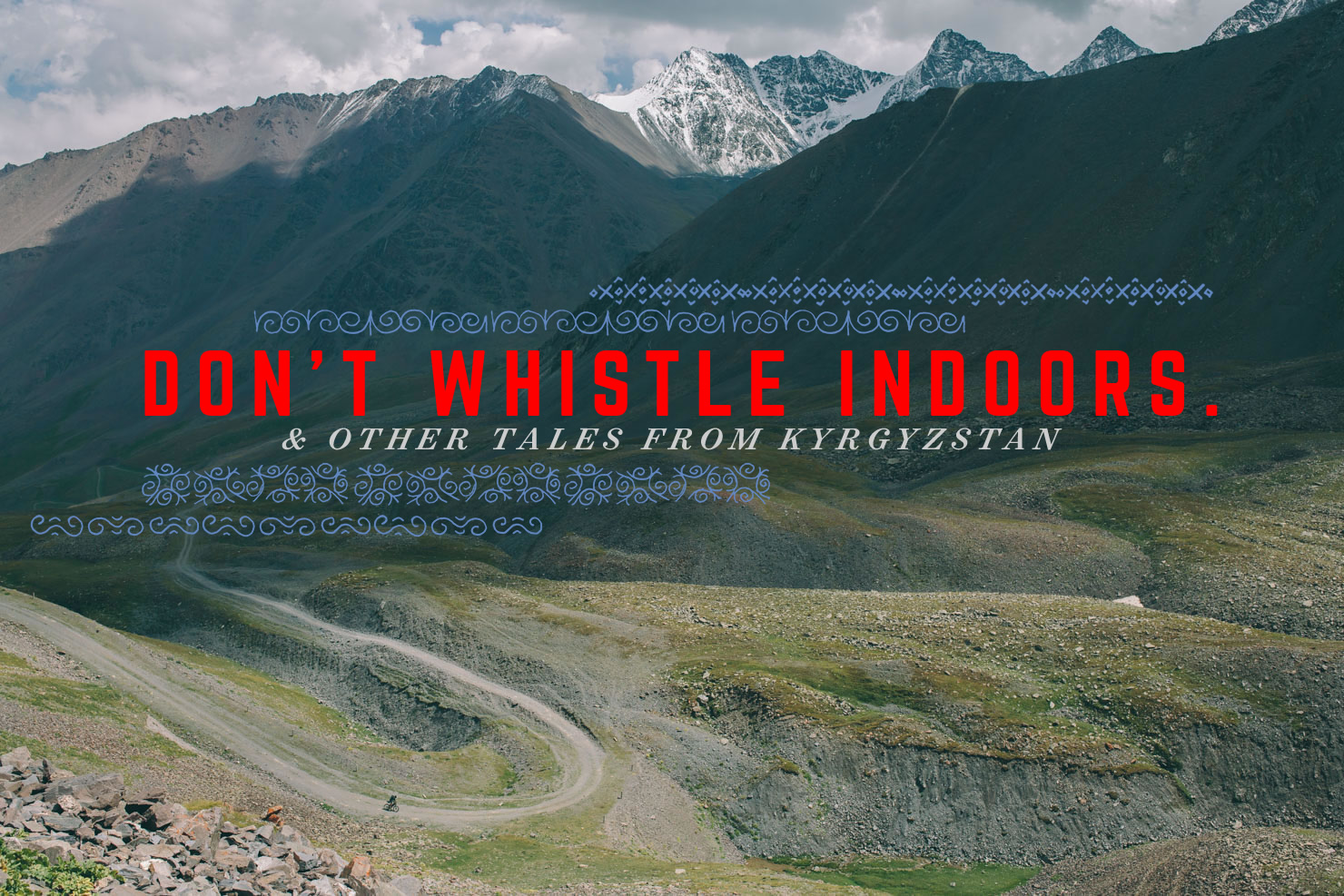

Kyrgyzstan is one giant, wide-open, fenceless, and mostly treeless campsite. The country is made up of a network of ragged, snow-capped spires that saw across the horizon and separate the sky from its expansive glacial river valleys, undulating grasslands, and a never-ending carpet of colorful wildflowers—the perfect place to whistle. I’ve never been much of a whistler, or at least I didn’t realize I was, but it seems The Andy Griffith Show had a bigger impact on my psyche than I’d care to admit. I found myself unconsciously whistling away every time I walked into a store, yurt, market, or restaurant, even though I’d learned that it was devastatingly rude to do so. Why is it rude, you might ask? I have my theories.

Expedition Day 1: Bread placement.

On August 1st, 2016, we pedaled away from the banks of Issyk-Köl, a beautiful deep-blue body of water, the second-largest saline lake in the world. Our initial grind took us from 5,500 to 12,500 feet in just over 50 miles. For the next few days, we meandered through a remote corner of the Tian Shan Mountains near the Chinese border. Thin air, rugged terrain, and tumultuous weather keep the inhabitants to a minimum in this part of the world, and there certainly aren’t any supermarkets.

Prior to leaving the capital, Bishkek, we’d stocked up on an odd selection of five days’ worth of packaged provisions. The labels were all in Kyrgyz or Russian, their Cyrillic characters impossible for us to decipher. Starkly designed packages in red, black, white, and gold reminded me of Kyrgyzstan’s Soviet past. We tried to guess the ingredients, mystery meat being the only sure bet. We had also heard that the graphics on the packaging often don’t accurately represent the contents. Because of this, we didn’t buy as much as we should have, and by day five, we were all running precariously low on food. I’d already eaten most of mine. Joe was down to a can of what turned out to be ground fish balls in an oily red sauce. Deep hunger was setting in.

A long and mesmerizing valley descent brought us back to a life-supporting altitude, and yurts began dotting the hillsides. We’d heard rumors of Kyrgyz generosity and warmth, and it was only a matter of time before we were offered a cup of chai, potent black tea. Liquid hospitality.

I stopped and rested my bike on a rock near a yurt to take a few photos. A small boy of two or three years was practicing his skills with a horsewhip. Within moments, we were invited inside by Chengiz, the keeper of the yurt. In typical Central Asian decor, there was a disfigured tangle of meat hanging on the wall, its species unrecognizable. A quintessential Silk Road scent hung in the cold interior, an amalgam of musty earth and dung smoke with a hint of unfamiliar spices. Chengiz offered us tandyr nan, a thick disc of bread reminiscent of focaccia. It was served with delicious homemade apricot preserves and small dishes packed with fresh butter.

Instead of stuffing the bread in my face as hastily as my stomach was telling me to, I tried to show some degree of decorum. I took a couple of bites and set it back on the table upside down. Chengiz gave me an odd look, so I quickly picked it back up off the table. Although I didn’t know at the time, I later read that bread is considered sacred by many Central Asian people, the result of a rocky Soviet past and widespread famine. You must never place it on the ground or leave it upside down.

Expedition Day 9: Never stand near a lactating horse.

After a long day of pedaling, we stopped to camp in an expansive field at the foot of a canyon. I pitched my tent and wandered off toward a farm to attempt to capture the portrait of an evasive Taigan—a skinny, long-haired sighthound known for its speed and ability to hunt wolves. The Taigan’s human, a little girl of about seven or eight years, smiled sheepishly for the camera. Her two brothers soon joined and motioned for me to visit their home just a stone’s throw away. I was invited in and offered bread, jam, butter, and the requisite kumis, fermented mare’s milk. Mikhail, the children’s father, called it “Schnappes” as he passed me a hearty serving in a dish. His conniving smile and gestural head tilt imparted that I had to drink it or I was a weakling.

Cocktail hour concluded with a milking demonstration. I asked if I could take a photo, and he smiled and gave me the go-ahead. With my eye to the viewfinder, I approached, lowered my stance, and shifted ever so slightly closer to the subject. Mikhail frenetically waved me back in a horrified, language-barrier-induced silence. Was it the camera or where I was pointing it? I wasn’t sure, but it was clear that I was doing something wrong. Evidently, horses don’t like strangers anywhere near them while being milked.

Mare’s milk is important to the people of the Central Asian steppe. It provides modest nutritional benefits and is believed, by some, to help in the treatment of several chronic illnesses, including tuberculosis and anemia. More importantly, milk holds significant value for the role it plays in the rituals and traditions of the people. Genghis Khan sprinkled mare’s milk on the ground as a way to honor a mountain for protecting him. Today, kumis is an essential element of any rite or celebration. The capital of Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, is even named after the paddle used to churn the stuff.

Expedition Day 13: Toss around the ol’ dead sheep.

After a serpentine climb through the mountains, we arrived at Song Köl. This glassy alpine lake lies at an altitude of approximately 3,000 meters (9,850 feet), and its surroundings are inhabited by nomadic shepherds during the summer months. There’s a modest tourist presence in the area in the form of yurt camps. Fortunately, where there are tourists, there’s bound to be food and alcohol. That night, we made camp with eight liters of Hawe beer in tow. It seemed like a good idea at the time, and the bottles pretty much jumped off the shelves. It turned out our eyes were bigger than our appetites for beer after a long day of climbing, and we hardly touched it.

The next morning, we pedaled away from the lakeshore and back into the mountains. Along the way, we stumbled across a game of Kok-Boru, also known as goat polo. As is the case with the version of polo many are accustomed to, Kok-Boru is a team sport played on horseback. However, instead of a wooden or plastic ball, opposing teams attempt to score by hauling the carcass of a goat down the field and tossing it into the opposing team’s goal. It’s an interesting display of horsemanship, to say the least, and the game is incredibly popular throughout Central Asia. It keeps crowds on the edge of their seats, kind of like a good game of our own American football, or “pigskin,” as we call it back in the United States.

Expedition Day 19: After-meal prayer.

Moving at a pretty good clip, I heard shouts from the grassy slope down and to my right. It appeared to be a family picnic, and they seemed insistent that we join them. We rode over, shook hands, and were immediately showered with bread, sweets, and, eventually, a turkey stew that cooked in a large black cauldron over a wood fire.

After 15 minutes of gestural small talk and laughter, it started to rain. We scrambled to get up and help them transport all of the dishes, baskets, and leftovers back up the hill to their vehicle. I realized there was a pause in the action as the grandmother, a glassy-eyed, wise woman of about 90, was leading a prayer. We stopped and paid respect. Later, I learned that at the end of a meal, Kyrgyz may say a quick prayer to honor family ancestors. They hold out their hands, palms up, and then everyone at the table covers their face in unison while saying a few words together.

Expedition Day 20: Damnit, don’t whistle.

Our last day of riding was indeed one of the best. The night before, we camped right off the doubletrack at the foot of the breathtaking Kegedi Pass. The magical evening glow gave way to another night of sleet and wet snow, but we awoke to sunshine. The riding was extraordinary as we spiraled down countless switchbacks nestled among some of the most dramatic alpine peaks I’d ever witnessed.

Once we descended below the treeline, we stopped to chat with Maksat, a shepherd standing at the roadside with a long cane and a dappled sheepskin draped at his waist. He invited us in for tea and proceeded to roll a cigarette from a scrap of newspaper that looked like the comics section. Maksat poured each of us a strong cup of black tea, and our charades-based conversation grew livelier as Maksat demonstrated his jiu-jitsu skills on Lucas. Joel decided to partake in the funny paper cigarette. He assured the rest of us that it was indeed tobacco. I drifted in thought at some point during the experience and realized that when I walked into Maksat’s house, I’d whistled a few notes. Damnit, “Why!?” I thought to myself.

The general superstition is that if a guest whistles indoors, poverty will befall that particular household or business or, more literally, as explained, money will fly out the window. I’m not a superstitious person, so I’m 99 percent sure I didn’t leave a wake of misfortune in this small Central Asian country, but why did I keep subconsciously breaking etiquette?

I considered that we weren’t actually indoors much during the trip. Kyrgyzstan is a country full of endless open spaces and short on permanent structures, so traveling by bike kept us out in the elements, no matter the weather. For three weeks, the four of us camped every night, ate outside, and only darkened doorways at the occasional store or yurt when invited in. All in all, we went indoors only once or twice per week and for very brief periods of time. The open landscapes, mountains, and fields became our comfort zone.

I realized that the transition from the outdoors to an interior space can be a stressful one. My theory is that I was nervous whistling, something akin to nervous laughter. Since being back in the United States, I’ve recognized that conditioned air can be more distressing than headwind, sleet, intense high-altitude sun, and frigid cold combined. All big trips involve some level of reverse culture shock. In this case, the adjustment involved getting reacquainted with interior spaces. For several days after returning home, I caught myself whistling indoors. After a couple of weeks passed, thankfully for my friends’ and family’s bank accounts, I noticed that the habit had faded away.