Self-Supported Principles: The Dos, Don’ts, and Blurry Middle

What does “self-supported” really mean? In this essay, Jackie Baker works to define it in the ultra-endurance bikepacking context and outlines three self-supported principles to help ensure the integrity and longevity of the sport. Find her takeaways from interviews with all kinds of racers and organizers and a massive gallery of images from some of our favorite events here…

PUBLISHED May 3, 2022

Words by Jackie Baker (@ohjaybay), above image by Photo by Dan King (@breakawaydigital)

Riding a self-supported race is intense, from the hours spent poring over Google Maps and satellite imagery of the route to understand things like the elevation profile, distances between resupply points, and what your goal finishing time will be, to selecting the pieces of gear you’ll take on your journey, to rolling into a town just before dawn on day three of the race and hoping the shop you’d discovered during your research is actually open. That preparation and effort are rewarded when you put all of the wildly variable pieces together and also manage to make your legs spin those cranks to the finish.

I am madly in love with this multifaceted sport. The freedom I feel while pedaling my bike, stacked neatly with everything I could possibly need for the next hundred miles, is unparalleled. And I’m unapologetically proud of the confidence and strength I’ve gained from figuring out how to pull myself through the long, dark, and shockingly cold miles until the sun and fatigue turn the route into sizzling-hot sparkles and rainbows.

Unlike many other competitions, there’s no race tape to keep riders on course. There are no chalk lines to define what’s out of bounds. There is no watchful eye of a referee or an attentive crowd to draw attention to a player’s infraction.

Self-supported is a concept so seemingly simple that our sport is named after it. Sure, you can roll with your besties, stay with pals, and rotate through who drives the party wagon behind you on any route, anywhere. But when you choose to participate in a self-supported bikepacking race, you enter into an agreement with yourself, your fellow racers, and the organizer to adhere to both the “understood” principles of self-supported racing and the event’s stated rules.

I asked many riders and organizers for their personal definitions of self-supported racing, as there are nuances to the “understood” principles, depending on an event’s distance, location, culture, and character. Still, everyone’s response aligned under one sentence from noted bikepacker and adventurer Bas Rotgans: “Taking care of yourself, not leaning on other people.” Easy, right?

Over the course of the past year, I’ve heard of and seen many instances of racers in self-supported events acting contrary not only to a specific race’s rules but also defying the basic principle of self-supported bikepacking. Here are a few examples:

- In a grassroots ultra-distance race where the premise is self-support, but where the organizer provides intermittent aid stations open to all racers due to the remoteness and lack of water resources along the route, a former professional road racer’s dad provided sag support for that racer until the racer had to drop out of the event due to a flat tire.

- In a multi-day self-supported bikepacking race, two racers who were registered as solo camped in a park. The next morning, one racer purchased supplies. The other racer arrived several minutes later. The racers split the supplies and departed together.

- In a multi-day self-supported bikepacking race, a racer stayed at a friend’s house one night. It is slightly off route. The next day, the racer suffered a massive mechanical, and contacted the friend, who supplied a new wheel. The racer carried on and later stood on the event podium.

At some point, each of these racers chose to lean on other people and not use their own mushy skull noodles to sort out their problems. Those who frequently race or follow the sport online can likely cite their own lists of observed controversial behavior.

Jenny Tough, who creates her own self-supported challenges around the world when she’s not winning events like the Silk Road Mountain Race and Atlas Mountain Race, eloquently argues that self-support is “why this sport is one of the coolest competitions around, especially in the cycling world. You can’t just be good at riding a bike fast to succeed – you have to be good at all the other stuff too. That’s what makes it such a dynamic event and so exciting to participate in.”

With more races and FKT attempts popping up each year, self-supported events are becoming more accessible and are drawing more new participants who haven’t previously experienced the challenges and triumphs of completing a self-supported event. It’s been incredible to see more people introduced to this previously niche discipline. I became enthralled with the sport in 2018, largely due to the amazing humans that make up the bikepacking community and the ability to race in my backyard.

It would be irresponsible of me to write a piece about self-supported bikepacking without a thorough conversation with one of the sport’s most accomplished athletes, Jay Petervary. Though that discussion could become its own full article, Jay offered the Tour Divide Race as the model for any subsequent self-supported event, as it has no true governing body and therefore requires each racer’s honesty and integrity. He is also quick to point out that no event can or should simply mimic the Tour Divide. He cites that when he first became interested, the previous riders of the route took such extreme measures to shield others from their experiences that they were unwilling to share even the most minute detail of information: “Do your research. Figure it out. We had to.”

These days, bikepacking’s largely jovial and welcoming group of passionate personalities has opened the gate to anyone who’s willing to do the honest work. For the most part, racers are happy to answer pre-event questions ranging from “what’s your favorite tire sealant” to “would I be crossing the line if I…?” Even if they won’t spill the tea on tire goop, they’ll definitely fill you in on the ins, the outs, and the blurry lines of racing self-supported.

Though it’s up to each event (or each community behind an established route) to clearly communicate its rules and codes of conduct to all participants, there are several guiding principles that shape those specific rules and help to ensure the integrity and longevity of this uniquely social solo (or sometimes duo) sport.

The Self-Supported Principles:

- 1. No Outside Aid

- 2. Stay on Route

- 3. Don’t be a Dick

Though it’s a short and easy-to-read list, it’s still often difficult to keep our moral compasses on route. Even the most well-intentioned and experienced racers misstep. Bikepacking, after all, is just real life with the added bonus of almost always being hungry and tired.

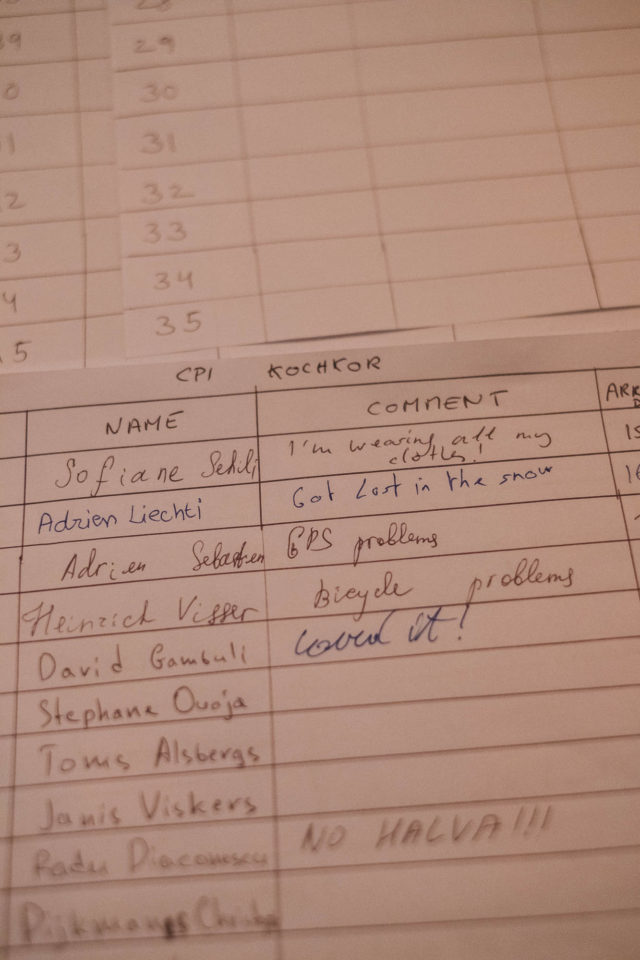

Atlas Mountain Race and Silk Road Mountain Race director Nelson Trees describes completing a self-supported event as, “You completed the race entirely under your own steam, using only your own equipment and without any outside assistance. When things got tough you got through them yourself. When things broke, you figured out how to fix them. And when you got lost you managed to get yourself un-lost.”

No Outside Aid

How do we keep the crisp lines that prevent us from falling off the edge of the road from becoming blurry? I mean this literally and figuratively. When you are out of food or water or your plan to resupply falls through because you’re ahead of or behind schedule, it can be tough to adhere to the principle of no outside aid.

Outside aid is normally defined as asking for or accepting any assistance that’s not commercially available to every racer. This principle extends to drafting and to directly helping another rider. If you can’t buy it on the route, you can’t use it. And, unless a fellow rider is in physical danger, you shouldn’t give aid to other racers.

It’s the “asking for or accepting” part that seems to be most frequently blurred. It can be so tempting to accept food, a room, or water from someone you meet in a small town that’s shuttered on a Sunday. But will the next rider who’s 15 minutes behind you be able to access that same amenity? If the answer is no, politely decline the offer and sort out a new plan.

Bikes break. Bodies get sick. Water runs out. It’s okay to take care of yourself and make sure you are safe. But if you accept outside aid, the honest thing to do is to scratch. In the least, communicate with the organizer and let them know what happened. Often, if you can fix your issue, you can still ride the rest of the route, proud that you finished the grueling ride to the best of your ability–even if you aren’t listed in the final race standings.

YES: If you need to buy something off route, like a visit to a mechanic, you can get yourself a taxi, travel to the shop, pay for the parts and services, and then pay for transportation back to where you left the course to carry on. Will some people argue that this scenario above is actually a “No?” I guarantee it. But it’s a far better solution than sitting on the side of the road, willing your bike to heal itself.

DEFINITE NO: Asking your Instagram followers for intel on where a local shop is.

YES: You can get a hotel room, as long as you pay for it and don’t book it in advance.

NO: Calling your mom and having her book it for you.

ALSO NO: Caching supplies along the route.

MAYBE: You’re riding along and a dude driving a RAZR with a cooler safely seatbelted into the passenger seat does a donut in front of you and waits for you to pass. Noting that you’re two humans crossing paths in the vast wilderness, he offers you an icy Busch Light. Can and should you take it?

Trail magic or serendipity (the random appearance of treats along a route) is viewed by some riders as fine to accept and by others as the first step toward the fiery pits below. In fact, it can be so disconcerting to be offered something by a passerby that James Mark Hayden created a lovely Serendipity Flow Chart for the L’Esperit de Girona. If only all of life’s choices could be so well illustrated!

CAUTION: When participating in a race with a Grand Depart, there’s a special vibe that comes from the routine of passing and then being passed by the same riders every few hours, day after day after day. The Mid-Pack Party Patrol, as I like to call it, is where many friendships are formed, where races within the race are born, and where I’ve been absolutely screwed when I hit the checkpoint and all of the beds were taken. Though I often try, I can’t pedal fast enough to stay in front of it. I just happen to naturally ride at Party Patrol pace.

This social scene can’t be underestimated and neither can the amount of information sharing that happens. I’ve been filling up water bottles and heard such detailed descriptions of upcoming miles that I’ve wondered if there is a secret layer of Google Maps accessible only by the dark web. Of course, most of those descriptions prove to be wholly inaccurate, but communicating about the thing you’re all doing at that moment is a natural part of the human condition.

The banter that flows while paperboying up a massive climb, the inevitable viewing of someone else’s line choice through a technical section, and the inability to pass up a store that already has three loaded bikes stacked in front of it–these are the unavoidable realities of racing with tens to hundreds of other people. These situations can easily cross the line into being too social to uphold the no outside aid principle. It’s here in the middle where it often becomes so easy to slip up and spend too much time together. Each member of the Mid-Pack Party Patrol has to take extra care to keep themselves within the self-supported boundaries amid the comfort anyone can easily find in the crowd.

Stay on Route

Thanks to modern technology, staying on route is quite easy. Most events and known routes have specific GPS tracks to follow, and you’re expected to do just that.

YES: You can veer off to hit a shop, hotel, or waterpark along the way, as long as you return to that given GPS track at the point you left it when you’re ready to continue on.

NO: Turning off your tracker while you’re racing, if you’re required to use one. Running out of power is a real scenario. Keeping your GPS on and recording can prove you stayed on route until you can get the tracker powered back up.

NO: Taking the shortcut the locals told you about in the bar.

ALSO NO: Hopping on the paved road next to the doubletrack when the dirt is clearly the intended route.

Don’t Be a Dick

Most of all, don’t be a dick. If the thing you’re about to do makes you feel a little weird, if you have to look over your shoulder to see if anyone is watching (unless of course you really have to pee, then please make sure no one is watching), or if you’d be bummed if someone in front of or behind you did something similar and bested you by three minutes because of it, well, you might be violating self-supported principle number three. Consider your options and then don’t be a dick.

YES: Being awesome and honest.

NO: Being a dick.

Who Cares?

Does it really matter if two solo racers team up? Is sleeping at a friend’s house that big of a deal? If you’re the racer trying their hardest to follow the rules, whether or not you’re in front of or behind the participant who is ignoring them, then yes, it really matters. If you’re the race organizer who has dedicated hours, days, and months to curating an ideal route and communicating expectations with racers, it certainly matters when participants choose to ignore it all.

If racers abandon the structure of self-supported principles and instead receive sag support from follow cars, are met by people along the route who are providing supplies, or are pre-arranging lodging, the race becomes a tour. The competition disappears and the challenge and satisfaction of navigating the route under your own power vanish in the dust cloud left by the Toyota Hilux that just rallied past you.

Ultimate Accountability

It’s you. It’s me. We’re ultimately accountable to ourselves for keeping the sport of self-supported bikepacking healthy and thriving by ensuring that the racing remains fair to all. Sonia Colomo, the 2021 women’s winner of the Across Andes Ultracycling Race noted, “If a race is called self-supported, anyone willing to participate should either adhere one hundred percent to the concept or not enroll.” It’s a choice you make long before you arrive at the starting line with your route plan taped to your loaded bike.

No one can force honesty or integrity. Unless entry fees include a remote drone for every racer, there’s no way to police everyone for hundreds of miles. Riders need to have enough respect for themselves, the sport, and the organizers to behave well and encourage others to do the same–and also to admit wrongdoing and remove themselves from the event when the best of intentions take a nosedive. Organizers need to take reports and admissions of violations seriously to prevent the spirit of the sport from becoming so diluted that it loses all of its sweet and spicy flavor.

Is the conversation over? Hardly. We still have several looming passes to climb. There are major topics like sponsorship, media crews, social media, dot watching, and on-route guest appearances to navigate. It’s a lot, so let’s start small. Let’s start with ourselves. Let’s make it a point to keep ourselves clearly within the boundaries of the self-supported principles and see how far we can each pedal on our own.

Related Content

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.