The Complete Route Planning Guide: Out of the Ether

Thanks to the wealth of online information, applications and digital maps that are now at our disposal, we’ve entered a golden age of backcountry bike route inception. Here’s our methodology, recommended tools, and a guide to resources…

One of the great joys of bikepacking is exploring new territory and finding adventure in the unknown. There’s always an appeal to ride for exploration’s sake; but setting out without a plan can result in bad situations, or at the very least, wasted effort. While paper maps and a compass open up new avenues for adventure—and help us get out of trouble when we need it—their digital counterparts take this to a whole new level.

Devising a good bikepacking route is one part art, one part elbow grease, and two parts R&D. In regards to the latter—given the ever-improving clarity of satellite imagery and the burgeoning range of mapping applications—the outdoor community is enjoying something of a beta boom. By virtue of the sheer volume of user generated GPX tracks that can be followed on any GPS device or smartphone, and the fact that mapping apps are more powerful than ever, there’s never been a better time to research and plan a bikepacking trip.

Nonetheless, with this blitz of data comes the eyes closed, finger on a map effect. Combing through such a mass of information can make distinguishing a well designed route all the more difficult. Anyone can follow a GPX plucked from one of the countless map-share websites these days — but who knows how that will turn out? We think it’s far more rewarding to travel a route that’s been crafted with thought, contemplation and experience. Or even better, to build one of your own. We’ve touched on route planning before; view the article here for an overview. In this post, we’ll be delving into the mechanics of it all.

1. Start somewhere.

The most important step is undoubtedly the first… figuring out where on the map to begin. Options are almost endless, governed only by one’s wanderlust, time, and pocketbook.

The marrow of a great bikepacking route is a healthy network of dirt roads, gravel and/or singletrack, depending on your interests. If you are new to bikepacking, consider trails you are already familiar with. Perhaps your favorite local rides could be developed into an overnighter, a multi-day ride, or more.

At this point, paper maps and state atlases – like Delorme’s Atlas and Gazetteer series – can also be a helpful in gaining an overview of the land, locating the main backroads in an area, and gleaning a sense of scale for your endeavour. National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps are another great resource for this, as is the Benchmark Atlas series, albeit more specific to the American West. In addition, regionally specific singletrack and mountain bike maps are often helpful.

Alternatively, there are countless online resources for finding such networks and getting inspired — public and federal resources, non-profit initiatives, mapping applications, references to historic tracks, and the burgeoning world of trail sharing sites. Here are few approaches:

1.1. Begin with an existing singletrack system.

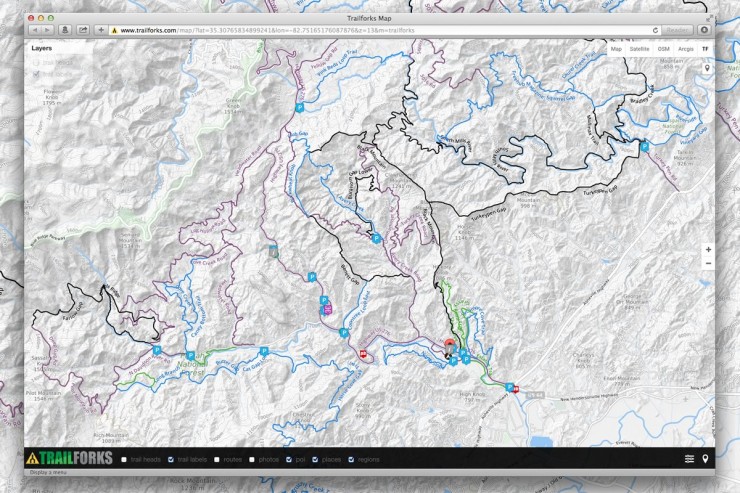

Two of our favorite resources for singletrack trails are MTBproject and TrailForks. Although the lesser known of the two, TrailForks is touted as having the largest database of mountain bike trails in the world. Not only does it feature an impressive map search, trails can be browsed by state and trail network. In addition, TrailForks has a smartphone app that allows offline GPS navigation. All the content, including photos, video and reviews, is user contributed. With an audience volume backed by Pinkbike, the popular mountain biking portal, it should only grow and mature.

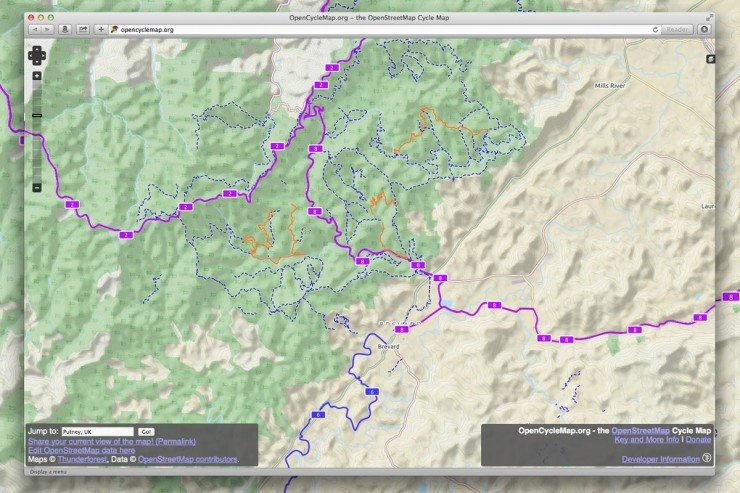

In addition, OpenCycleMaps (which is available as a viewable layer on most planning apps, such as RideWithGPS) is quickly gaining may singltrack trails and networks…

MTBProject is a similar project developed by the IMBA in the US. The system is a little more clunky to browse, but it does have quick access to the Best Of trails, as well as IMBA Epics and BLM Treasures. It also has loops and full rides submitted; some of which can be easily segmented into overnighters, such as our Pisgah Long Tour.

1.2. Discover Forest Service Roads.

Some of the most reliable off-tarmac networks, both here in the US and abroad, are forest service roads. FSRs were typically created for logging exploits and fire prevention. They can be range from rugged, rocky and rutted dirt roads, to well-maintained gravel surface, to long forgotten tracks that have devolved to singletrack. In the US, we’re blessed with a high concentration of FSRs throughout our National Forests. There are around 150 National Forests boasting almost 190 million acres of land throughout the United States — an area about the size of Texas, or around 8.5% of our total land mass. To help make sense of it all, the Forest Service has this nice locator map.

1.3. Base it on an IMBA Epic.

The IMBA’s (International Mountain Biking Association) Model Trail ‘Epic’ designation is their own class of bucket list worthy trails. Although this program is currently in flux, their list of Epics provide a good skeleton network for a range of bikepacking routes. Most Epics run anywhere from 20-80 miles and usually involve a fair amount of elevation gain. In fact, there are several classic routes that are based on IMBA Epics (or vice versa). The Huracan 300 uses the old Santos Epic. The Virginia Mountain Bike Trail incorporates Douthat State Park and a portion of the Southern Traverse. The Stagecoach 400 incorporates Cuyamaca Noble Canyon. And the Trans North Georgia incorporates the Pinhoti Trails. Similarly, IMBA created an Epic from the southern section of the Colorado Trail. And last year the Black Canyon Trail became an Epic.

1.4. Dig in to a trail share site.

WikiLoc is growing resource internationally, boasting almost five million trails for hiking, cycling and many other activities. We’ve tapped into it for routefinding all around the world. In Uganda, we used it to unearth a wealth of MTB routes from a local cycling club. We were able to download several GPX files and stitch them into our larger Trans-Uganda route. Although WikiLoc is big and a little cumbersome to navigate, they are improving it regularly, so we expect it to grow into an even greater resource.

Another of our favourite trail share sites is RideWithGPS, which is an excellent resource both here in the U.S. and abroad. RideWithGPS offers a social share approach to trail sharing and is becoming a good resource for finding rides and routes. And as we’ll discuss more in section 3, RWGPS has its own navigational app and highly functional planning tools.

BikeMap.net is another growing entity with a well designed search funtionality. We’ve used it to research rides around the world, though we’ve found much of the route data on the site is of the on-road variety.

1.5. Follow footpaths and bridleways

While this isn’t as relevant to U.S. based travel, there are countless networks of footpaths and bridleways throughout the world. In England and Wales, a rich vein of bridleways offer access through private land, while Scotland has some of the most bike-favourable land access laws in the world. Traditionally, information for these has been gleaned through incredibly detailed Ordnance Survey maps, all of which are now available online, via the likes of their own mobile app.

In continental Europe, especially Spain and France, there is an incredible network of GR Footpaths, walking routes which use an ancient network of trails, dirt tracks and roads. The ‘GR’ stands for Gran Recorrido in Spanish; in French it translates to Grande Ranndonée, which sounds a bit more inviting for bike travel. By way of example, when designing the Altravesur, we based it on the GR7 and tied in a half dozen more GRs. The European Rambler’s Association (ERA) has developed a long-distance trail system of footpaths with numbered routes from E1-E12 (each currently in various phases of completion). In addition, The European Cyclists’ Federation (ECF) is coordinating the development of a network of high-quality cycling routes that connect the whole continent, although these are mostly paved.

In most developing countries where walking and cycling are still a primary means of transportation, there are plenty of opportunities for bikepacking. Scour Google Earth’s satellite imagery (see below) to find potential paths. Throughout Uganda we followed footpaths that weaved in and out through villages. In South America, we’ve connected mule trails and senderos. Most were found through OpenCycleMaps or via satellite maps.

1.6. Take in a Rail Trail, Towpath, or historical trail.

All over the world, abandoned rail lines are being converted to trails. In the U.S. the Rail-to-Trails conservancy supports over 30,000 miles of rail trail nationwide. In Spain, the Via Verde system has many great trails. Even developing countries such as Uganda and Bolivia have abandoned rail lines that are used as trails. Another resource is RailTrail.com, a directory to world rail trails.

1.7. Use OpenCycleMaps.

Last but certainly not least… In development since 2007, OpenCycleMap is a base layer global cycling map project that’s based on data from the OpenStreetMap project. At low zoom levels it is intended for overviews of national cycling networks, which it does well. But it also harbors information and tracks for a lot of singletrack networks, greenways, existing bike routes, and all the gravel and dirt roads that are in OpenStreetMaps. So not only is this map good for research, it also makes a fine base layer for drawing your route (which we’ll get to in section 3). A variety of mobile apps use it in one form or another.

2. Pin down points.

Before you get to far down the trail, there are a couple basic requirements for planning a bikepacking route:

2.1. Plan a place to sleep.

While it’s debatable whether this should be number one or two in the process, an important step should be to identify a campsite or a general area to camp within. Without a reasonably permissible and safe place to pitch your tent, it’s pretty tough to build a route. Of course the parameters change based on the country where you’ll be bikepacking, but the same general rules apply.

Here in the US we have several types of public land. National Forests are the most common, but there is also BLM (Bureau of Land Management) land, state public land, game reserves, National Parks, and various other designations. They all have varying rules regarding backcountry camping. National Forests are probably the most lenient and typically have designated sites as well as generous provisions for backcountry camping. BLM land is also generally a safe bet and often has camping opportunities. The rules for state-owned lands differ widely. And of course there are Wilderness Areas which have far stricter rules and prohibit bicycles completely (although this may evolve). It’s best to identify where you intend to camp, and research that entity independently. Needless to say, as with all backcountry travel, follow the Leave No Trace principles.

Another option is to simply find an established campground. This doesn’t have to mean you pony your tent up next to a bunch of RV campers. There are plenty of lesser used National Park campgrounds, backcountry camps, State Park campgrounds, game reserve camps, etc. In addition, look for hiker huts, shelters, or gites. The GR247 has a series of ‘refugio’ hiker huts and can be ridden without a tent. These are often noted in various basemaps, including the OSM Outdoors layer included with RideWithGPS. And of course for folks who want to pamper themselves a little bit, there are also hotels, hostels, and WarmShowers hosts.

And then there is good ole stealth camping. This doesn’t always mean ‘illegal’ camping. Sometimes there simply aren’t laws or rules for camping. In this case it may be acceptable to find a hidden spot, camp, and leave it just as you found it. There are also cases where there is no public land. Ask a landowner if you can camp discreetly on their farmland. Nine times out of ten, they’ll appreciate you asking, and may even invite you for dinner. In many countries overseas, stealth camping can also take the form of abandoned buildings or empty animal shelters — bike-shacking, as it were — though these tend to be discovered ad hoc, rather than planned in advance…

2.2. Stage, start and Finish.

Considering the logistics of getting to and from your ride should also be part of your route planning recipe.

For routes ranging from 24 hours to a couple of weeks, a loop is always a good approach. It reduces logistical challenges — having the same point to start and end is always ideal for parking and staging the trip. This spot should not only be safe, but be well thought out to make your route flow well.

Conversely, many big routes or ‘trans’ routes are linear. Shuttling, public transport, or even hitching is required. Using a shuttle or the buddy system with two cars is pretty straightforward. Hitching depends on both luck and the area you’re in… Logan once found himself stranded after the VMBT. It seems no one wants to pick up a dirty bearded person in Virginia…

2.3 Public Transport

For bigger routes, public transportation usually comes into play. Here are some aspects to consider:

Trains are a primary means of getting to the route start — or getting back from the finish — for many European bikepacking routes. The Altravesur uses Spain’s Media Distancia lines to get from Madrid (which has an international airport) to the route start and then back to Madrid at the end. These and other such lines often allow bikes to be rolled on and off, and stowed in the luggage area in your compartment. Always check the bike policy — some require bikes to be bagged or boxed, while others have restricted access on certain lines or at particular times.

Amtrak has taken notice of the bike community and has recently expanded it’s offerings to include several ways of transporting your bicycle on many of their routes. All Amtrak lines allow boxed bikes to be checked, granted that particular train handles check baggage. With with regards to route planning, on select trains they offer two additional services for assembled bicycles. Walk-Up or Checked Bicycle Service allows standard full-size bicycles to be transported in bicycle racks located in the baggage car. Passengers are not allowed in baggage cars, so Amtrak personnel will store and secure your bike in the bike racks. This service is only available at select stations. Advance reservations are required. Walk-On Bicycle Service allows standard full-size bicycles to be carried on and stored on board in bicycle racks on these select certain trains.

Buses can be a fantastic option, depending on where you are. Unfortunately, they all differ for rules and regulations. Outside of the States and Europe, most tend to be pretty lax in terms of regulations, though we’ve been on busses in South Africa that required bikes to be boxed. Others have racks on the outside. Or they simply toss them in cavernous luggage compartments underneath. In Latin America and Asia, buses reach every nook and cranny in the backcountry. In such continents, there’s a great economical option if your route dictates a long ride back to the start.

Flying with a bike is often necessary for extended trips. There’s a wealth of info out there on flying with a bike. And while it’s not usually part of the route, unless it’s a long, linear journey, there’s a chance you’ll do it if your route is faraway from home. Stay tuned for a detailed guide that we have in the works.

Public ferries and boat systems are another way to create an interesting aspect to the route and sometimes allow for a return trip or a complete loop. For the Congo Nile Trail the ferry at Cyangugu brings you along lake Kivu back to the route start. Ferries also can play a major role in routes in the Pacific Northwest, as well as many other coastal regions.

2.4. Don’t forget water and resupply.

Planning water and resupply points is not always necessary, especially for shorter routes, or routes that often pass through urban areas. However, when considering a 3+ day bikepacking trip, water and food replenishment is absolutely necessary. Lakes and ponds are one thing, but it’s often difficult to identify legitimate water sources (springs, streams, etc) via map or satellite imagery. In dry climates look for patches of green to help locate streams and springs. Some form of water filtration system is generally recommended. Animal watering fountains are another last resort.

As for food, gas stations are generally a safe bet for basic sustenance, even if it tends to be on the highly processed side. If resupply points are few and far between, consider carrying dehydrated food, both sold commercially in camping stores or made in a domestic dehydrator.

3. Make it extraordinary.

While it’s more than possible to have an incredible experience on great trails and terrain alone, sometimes routes beg to encompass something more. Often the theme is what started the route in the first place, such as tour of a collection of peaks, the most interesting way to cross a specific region, or a route that takes in the best trails and breweries of an area. Other times it’s a matter of peppering in punctuation to give the route some flow. Here are some points reiterated.

3.1. Design it around places of interest.

Basing routes on particular sites or stops is a good approach. How about breweries, historical landmarks, hot springs, swimming holes, or scenic viewpoints? In addition, sometimes the crown jewel of a good route is a campsite with a view, fishing hole, or interesting natural feature.

3.2. Add historical intrigue.

Bikepacking is a chance to dig deeper into the lands across which we ride, so sharing their past can be as interesting as experiencing them in the present. A historical context to the ride you plan can imbue it with a rich, textual depth that goes beyond the simple thrill of a physical adventure. Take this historical New Mexico bikepacking route for example.

3.3. Watch the geography.

Sometimes what attracts one to a specific place is its land and natural wonder. Other times, it’s gazing at a topographical map and finding an anomaly that beckons for some reason or the other. Prior to our last segment of the Altravesur, the time spent studying an interesting geographic formation — the canyon of Rio Mocar — paid off in spades. The canyon stood out on the terrain map like a sore thumb. It was obviously a deep trench that snaked towards the sea. Upon riding it we found an amazing stretch of singletrack.

3.4. Timing is everything.

Obviously weather is a major factor for any bikepack. Other times it controls it. Snow routes require a good winter, and some places are impassible during monsoon season. In addition, consider events, such as the Solstice. Swift Industries based their Campout on it. The extra long days allow for more exploration, longer days in the saddle and more relaxing time. Also, time your trips based on natural occurrences, such as the spring show of flowers in the desert.

4. Draw the Map.

Now it all comes down to putting it together. At this point some may choose to go ride armed with maps and notes, and record the GPS route along the way. And that’s a fine process. Our’s is a little different though. With the right tools it’s feasible to never record a GPS track. Of course this isn’t always possible, so it’s a good practice to record either way. But, using one or more of the online applications below you can create a route, load it on your smartphone and set off.

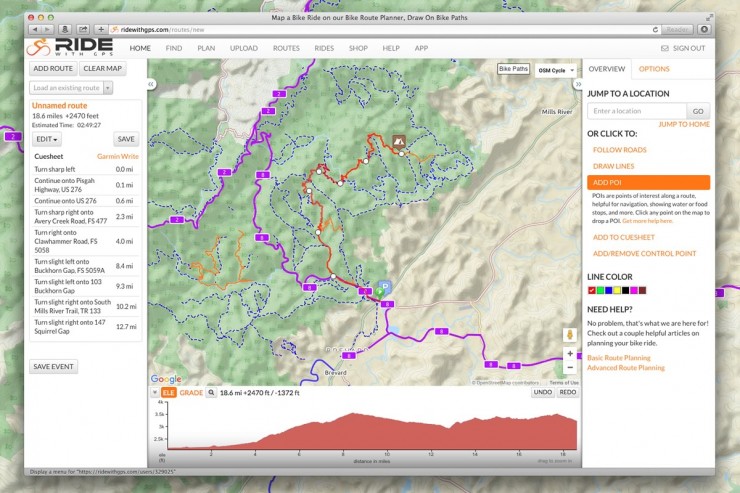

RideWithGPS

RideWithGPS is our favorite amongst this grouping. It not only has a great toolset for planning a route, it has a well chosen set of basemap layers, including our favorite, OpenCycleMap. As mentioned above in section 1.7, OSM Cycle displays a significant number of singletrack networks, hiking paths, cycle routes, rail trails and more. RWGPS’ Plan a Route mode enables you to click points on the map to draw a route, and with the Follow Roads tool, it actually traces these paths, including singletrack. It then compiles an elevation profile and provides a suite of tools to further refine your route. Another function that’s ideal for bikepacking routes is the ability to add POIs (Points of Interest). With this feature you can add waypoints by category, such as Convenience Store, Camping, and many other options. Each is represented by a relevant icon.

The program also allows multiple tracks to be stitched together. You can start with a downloaded GPX or KML file, upload it and build from there. You can also add additional GPS paths into a route. For example, the Trans-Uganda is a compilation of over 6 GPX tracks from a local cycling club as well as a lot of other custom drawn and planned tracks.

Once you finish your route, simply download the GPX and add it to your GPS or smartphone app. Furthermore, there is a RWGPS mobile app that also allows offline navigation by downloading map tiles. With this app, you can browse your routes and download them to use as navigation.

Granted the RWGPS Plan a Route application takes some practice, it’s truly a great tool. RWGPS offers a detailed help area which includes a few how-to videos on general topics such as Route Planning or more specific advanced techniques such as Combining and Splitting Routes. In addition, based on a lot of use and head scratching, here are a few tips we put together.

- The distinction between Rides and Routes can be a bit confusing. Sometimes when you upload a track, it saves it as a Ride. Make sure to ‘Copy To My Routes’ and work on it as a Route for further planning.

- When in Plan or Edit mode, use the OSM Cycle base map from the dropdown in the upper right; this provides access to many singletrack networks, rail trails, cycle routes, and more.

- Also while planning, switch between basemaps to get different perspectives. Sometimes forest roads are missing from OSM layers, and conversely the Map layer is missing a lot of trails and paths. Also, the satellite layer is indispensable for identifying unpaved tracks.

- Make sure the OPTIMIZE FOR setting is set to Cycling or Walking. This ensures the Follow Roads tool traces singletrack.

- Sometimes when going between trails and roads, or other tracks, the FOLLOW ROADS tool won’t complete the line and instead reroutes around. Simply click UNDO, and then use the DRAW LINES tool to manually bridge the gap. This often occurs at water crossings as well.

- When joining multiple tracks, there’s a delay when you can add recently uploaded GPX/KML tracks to an existing route. Give it :30 and it should show up under ‘Load an Existing Route’ in the upper left.

Google Earth

Big Brother to Googlemaps, Google Earth is an incredibly powerful tool for planning – and dreaming up – off grid adventures. With its incredibly sharp, interactive imagery, use it to research a proposed area, checking out the lay of the land and expected terrain. Depending on the area in which you’re digging around, it even includes a POV perspective – handy for finding out if you the ride you’re creating is dirt or paved.

We often use Google Earth to quickly create a rough KML file of an intended journey, before uploading it to our devices. If you’re worried about it taking the fun out of exploration… don’t be. Google Earth opens up parts of the world where reliable maps are few and far between, and can really help with those ‘I wonder if there’s a way through there’ moments.

BikeMap

BikeMap.net is another elegantly designed planning tool. The application’s basemaps are good and include OSM Cycle. They also have a very simple tool set that’s easy to use. It does not, however, allow multiple track stitching like RWGPS. And the POI icon selection, while nicely designed, is limited (with only hotel, water, shop or photo).

TopoFusion

TopoFusion is GPS Mapping software developed by Scott Morris, a longtime bikepacker and founder of Bikepacking.net. It’s a good planning tool and allows drawing, cutting and splicing. A big bonus is that you can easily switch between multiple sources of topo and aerial maps, allowing you to verify existence of a trail/road from different maps, increasing confidence and cross-referencing. As most of us know, just because a route shows up on one map or aerial doesn’t mean it’s actually there or is viable. It’s great for elevation/grade estimation, of course, too. Unfortunately, it’s only available for Windows, so being Mac users, we haven’t had the opportunity to try it.

MapMyRide

MapMyRide.com is another application purpose built for route planning. However, it doesn’t include OpenCycleMap base layer and the tools and functionality aren’t up to par with RWGPS.

Gaia GPS

As discussed in our Using a Smart Phone as a GPS feature, Gaia is one our favourite navigational apps. Those who use it can also access a web version that features all the same basemaps. As a planning tool, Gaia’s interface isn’t nearly as developed as RWGPS. But it’s still very useful, especially as any files you create are automatically synced to your mobile device – and visa versa. Note that if you need to do so on the fly, you can also plan routes in the mobile app itself. Although a little fiddly – depending on the size of your phone – this can be a great way of sketching out an intended route and estimating its distance, while you’re out in the field.

5. Ride, camp, tweak.

Incontestably, the ride is where the meaningful magic happens. This is the proof of concept and a chance to validate the research — not to mention enjoy the ride. It’s sometimes surprising how research can pay off. On our simple Croatan Gravel Vanish overnighter, the National Forest roads coupled with a stretch of singletrack bridged two networks and made for a most interesting overnighter trip. This was a prime example of finding a national forest, digging into the tracks in and around it, and using several of these tools to devise an interesting bikepaking route out of thin air.

Sometimes there are hiccups though. Coming upon a road that’s been thwarted by private land is a common occurrence. It’s also often that a better alternate track is found during the ride. Take notes along the way. With Gaia GPS app it’s easy to make waypoint notes regarding trail quality or where there’s an unexpected twist in the route. From there it’s often easy to retrace the line on the overall route plan with RWGPS or another tool. And of course all of the magical spots you find along the way can be noted too.

Note that this guide is in flux. In the spirit of a lot of the trail sharing and open source maps we mentioned here, we’re considering this an open source guide. If you have resource to share, please let us know. Obviously, we can’t include everything, but if we see anything compelling and relevant, we’ll add it above.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.