Over The Top: The Wayfarer Centenary Weekend

Do you consider California the spiritual home of off-road riding? Half a century earlier, cyclists were pitting themselves against rough and rutted drovers’ tracks on skinny tyred bikes. We head to North Wales to commemorate a particularly noteworthy off-road tour that took place on a snowy weekend in 1919, with the oldest off-road bike touring club in the world…

PUBLISHED Apr 11, 2019

Held just a couple of weeks ago, the Wayfarer Centenary Weekend was an event that commemorated the crossing of Wales’ Berwyn Mountains, at the tail end of March 1919, on a particularly rough and rutted drovers’ track… during an especially windswept and snowy weekend. But what makes this undertaking so worthy of celebrating? Aside from the fact that its high point, Pen Bwlch Llandrillo, is an especially beautiful spot from which to soak in the surrounding views, the crossing was bookended by unusually harsh weather conditions, encouraging Walter MacGregor Robinson, a cycling journalist of the time known as ‘Wayfarer’, to write up what was to become a classic trip report, entitled Over The Top.

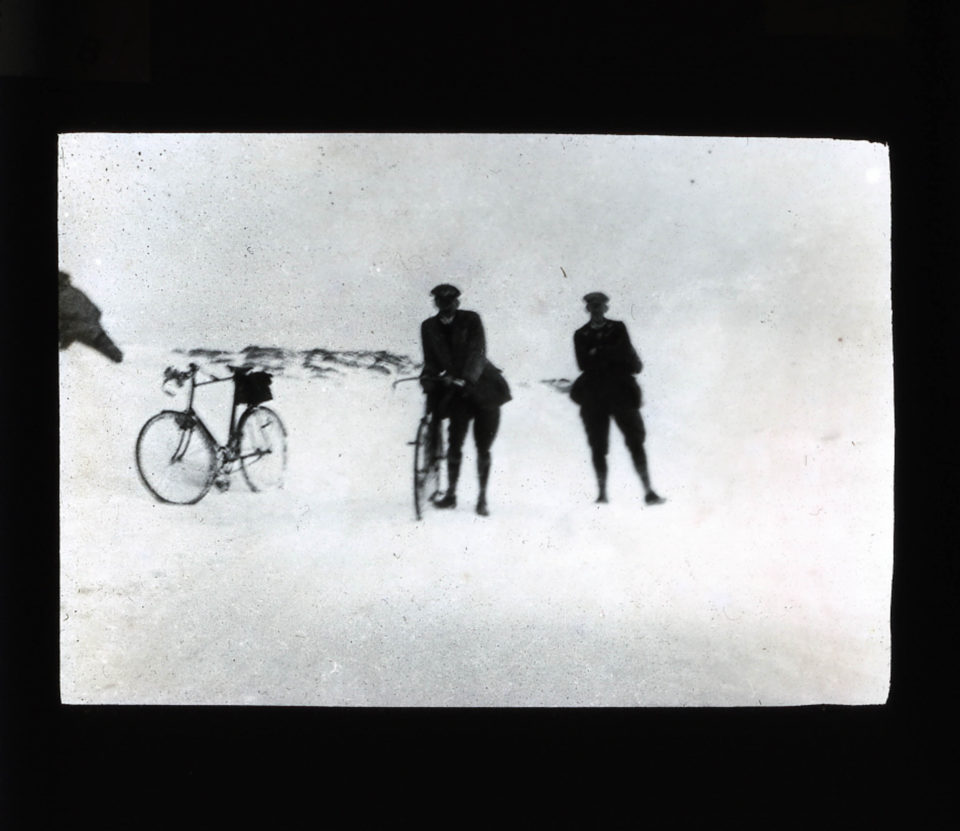

Recounting a long weekend riding with friends, bagging the highest passes in Wales along the way, Over The Top was read far and wide, inspiring other hardy souls to seek the road less travelled on their bicycles. It was a crossing that was also captured in a series of iconic photos, none more so than the image of two men in their pantaloon-like cycling gear silhouetted against the snow, the graininess of the exposure doing an especially good job at representing the sheer grittiness of the ride.

Wayfarer’s original account makes a wonderful read, complete with period vernacular and a sense of spirit that still resonates amongst bikepackers today. In particular, I admire Wayfarer’s notion of the importance of riding certain routes to celebrate the beginning and end of the ‘on season’ and ‘off season’.

“Just as I celebrated the departure of “the Season” last September by means of a cycling week-end trip, so I celebrated the end of the “off-season” in March by a cycling (and walking) week-end trip. I am, indeed, a bit of a stickler for observing these feast days and holidays, deeming it fitting that, when the “sensible cycling season” comes to a close, one should note that fact in a proper manner, just as, on the passing of the “off-season” (when “nobody rides for pleasure”), one should do something special to mark the event.”

The weekend was also a timely reminder of Wayfarer’s impact on off-road touring. His fabled writings and lantern slide lectures of the 1920s and 30s were one of the driving forces for founding the Rough-Stuff Fellowship in 1955, as was the rising tide of motor traffic on the main roads, at a time an increasing number of cyclists were being drawn to road racing and the glamour of all things ‘continental’. In many ways, it was a climate that is echoed by the one we find ourselves in today, a hundred years later.

To begin the weekend, Mark Hudson, archivist of the Rough-Stuff Fellowship, held a lantern slide evening in which we all were regaled by images of outings from the 1950s onwards, in the very same spot – the West Arms Hotel – where Wayfarer had spent the night before his snowy crossing. Not only that, but Mark had also gathered together various RSF memorabilia, including a set of Carradice-branded ‘micro panniers’ that were remarkably similar in concept to what’s available today. What goes around, comes around. Pints of beer and ciders in hand, we imbibed our way to a backdrop of gutsy adventures on ridiculously skinny-tyred bikes. I expect the RSF could be considered the gurus of ‘under biking’, simply beacause that’s what was available at the time! Their rides, including day trips, weekends away, and longer undertakings, were initially concentrated around Europe, before veering east to include epic jaunts across the Himalaya, trips that undoubtedly would have been especially forward thinking at the time.

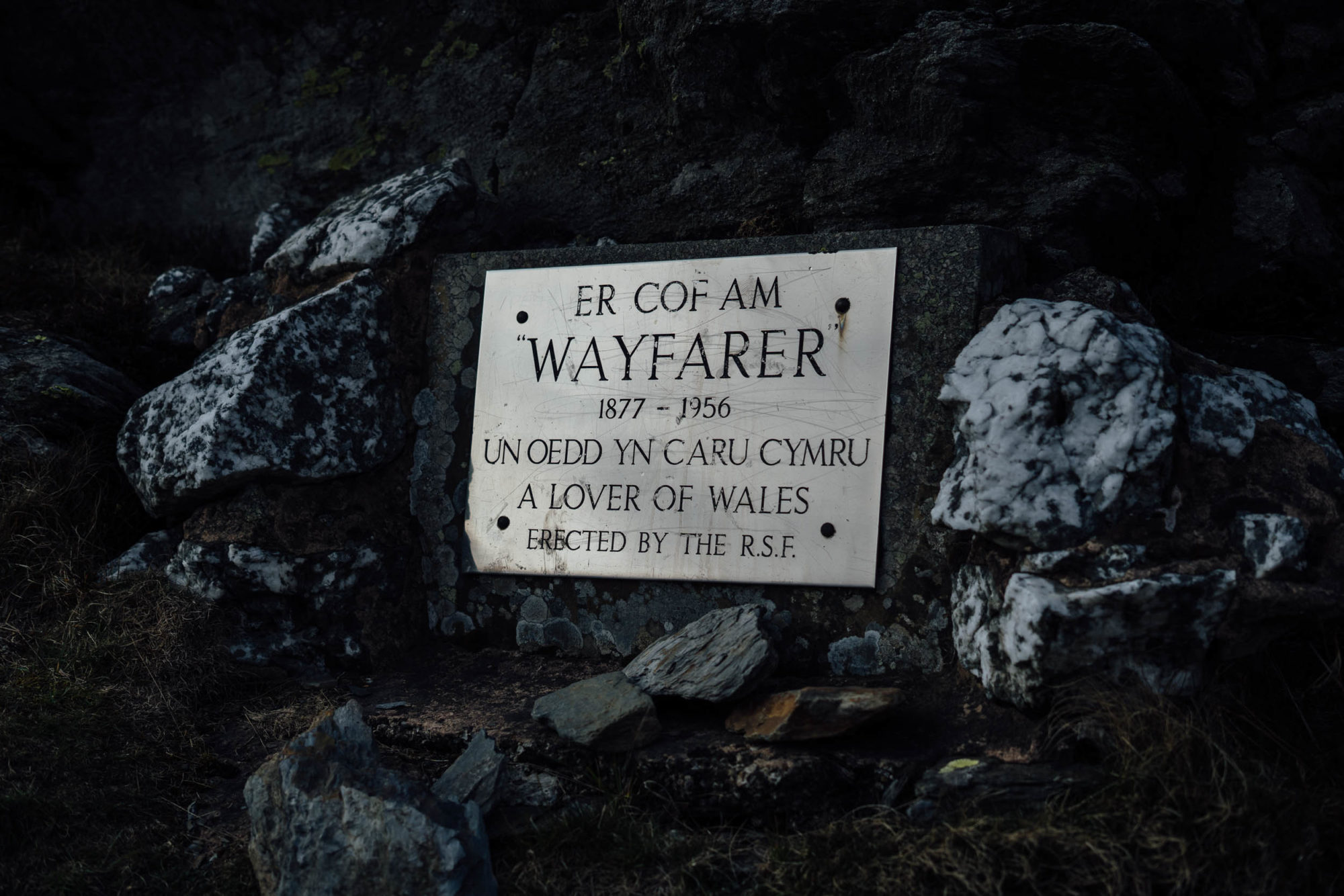

Then came the crux of the weekend: a reenactment of the crossing itself, a hundred years later to the day. At the time, three cyclists rode through blizzards from Chester to reach the West Arms in Llanarmon, some 50 miles, where they spent the night. The next day, they were up early to cross the Berwyn Mountains via a rough and rutted drovers’ track that crosses over to Nant Rhydwilym, cresting the col at Pen Bwlch Llandrillo. Despite snowdrifts, a whiteout, and a barely discernible road, the three touring cyclists completed their endeavour before continuing on with their ride. A memorial stone was first installed by the Rough-Stuff Fellowship in 1957, following Robinson’s death a year before, celebrating the ‘Wild Wales’ that he so loved, and it was its replacement plaque that we were headed for.

Not that conditions were quite as wild for us. Instead, blue skies and t-shirt weather encouraged general loitering outside the pub, and the inspection of a remarkable array of cycling machines that represented the century of cycling technology that had developed in the interim. Older steeds – a Sunbeam, Rotrax, and an FW Evans, to name a few – rubbed shoulders with contemporary bikes complete with thru-axles and carbon rims, making for quite the eclectic gathering. Organiser and author Jack Thurston made sure we were primed, letting us know that the unmade track was “very rough and rutted in places and boasts some exceptionally large puddles after heavy rain. Minimum requirements are a touring bike and a sense of adventure.”

Although our intentions for the day varied as did our ages (25-75) we all set off together, first on back lanes, then on the drovers’ track itself, navigating merrily through deep puddles, as promised, to the col five miles away. There, a plaque to Wayfarer, A Lover of Wales, marked the top of the pass, along with a solid steel box that contained a visitor’s book filled with various donations; whisky, beer, and snacks for those who were making the pilgrimage during less fortuitous weather.

The atmosphere was relaxed and unhurried, no doubt a far cry from the day we were remembering, given the difference in conditions. Had the same weather presented itself and been tackled by a few hardened bikepackers on fat bikes, much of it would no doubt be rideable. But that’s not really the point. This ride represented a defining experience of its day, and besides, for those who’ve always been dubious about the stoic merits of the hike-a-bike, Wayfarer had a certain way with words that may help convince you:

“And is this cycling? Per se, possibly not altogether. Some of the way over the mountains was ridden, but for the most part it was a walking expedition, as has been made clear. It should be emphasized, however, that only through the medium of cycling was the outing in any way possible. Prefaced by a 60-mile ride and followed by one of nearly 50 miles. I claimed that, broadly, this is cycling. At least, it is cycling as I understand it, for my conception of the pastime includes much besides main roads and secondary roads and much beyond the propelling of a bicycle. And, though I am almost a “one-pastime man”, I fling wide the boundaries of that pastime and include whatever is incidental thereto. Some of the best of cycling would be missed if one always had to be in the saddle or on a hard road.”

I didn’t get to see the period bikes in action, piloted by a group of elderly gentlemen in long, woolly socks, designs that would doubtlessly be greatly admired by Californian hipsters. But we had Isla Rowntree with us; not only is Isla a former national cyclocross champion, but she also founded Isla Bikes, the company responsible for the thoughtfully designed children’s bicycles we see today. Isla had taken this reenactment to the next level and was riding a singlespeed Raleigh from the 1930s, tearing up the Welsh countryside with a 48T chainring. The Raleigh was shod with Dunlop 26×1 ⅜” tyres and her garb included a ‘baker boy’ style cap, silk bow tie, breeches (WW2 women’s land army), 1940s tweed jacket, waistcoat, and brogues. Further meticulous attention to detail was provided by a cotton handkerchief, a tin of spare valve cores, and my favourite accessory, a most beautiful Philips pocket cycling map 1:200,000, printed on silk to be waterproof, with suggested cycling routes and junction distances. Nothing’s new, right?

From the pass, we let loose down a rough doubletrack. On my 2.8″ tyres, I could just let go of the brakes. Those on older contraptions had to hold back. Somehow, doing so actually felt more appropriate; a chance to soak in the scenery. In a way, each bike, no matter the era, represented the best in its day, in terms of resilience, design, and weight. It’s interesting to consider that whilst the quest for the ‘best’ or most appropriate setup is hardly a new one, the Wayfarer Centenary ride was also a useful reminder that it’s not all about the bike. It’s about getting out there and pushing if you have to. Some forty more hilly miles ensued, up and down tightly woven valleys, across the river Dee, and past such Welsh tongue twisters as Cynwyd, Pontcysyllte, and Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog, by way of a pub lunch. Eventually we made our way back from whence we came, first across the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, then on a gravel path alongside the Llangollen canal, and final on backlanes where old and new steeds formed a paceline home.

The next day, a few of us headed into the hills once more, including Mike and Mike, whose profiles have already graced this site. In some ways, our loop was an even more fitting ode to Wayfarer, mainly because it included a number of hearty yomps and bike pushes through tufty, tire grabbing moorland. Doing so felt perfectly in tune with those who came before us, and was certainly in keeping with the Rough-Stuff Fellowship mantra, “I never go for a walk without my bike,” which will be familiar to anyone who follows their fabulous Instagram feed. The loop we concocted, traced out on an old Ordnance Survey map, included bagging the high point of Cadair Bronwen, before a protracted hike-a-bike that connected us once more with Bwlch Nant Rhyd Wilym, descending the rocky drovers’ track we’d climbed the day before, finally finishing up at the pub in the West Arms Hotel, where it all began.

The weekend may not have been bikepacking as such. But it was a perfect way to remember an individual considered by many as a forefather of off road cycling, who passionately promoted what it is we enjoy most about it: striking out on the road less travelled, be it through adversity or on a fine, sunny day… and in doing so, perhaps bringing home a good story to tell.

Jack Thurston’s excellent Lost Lane series can be found here; see Lost Lanes Wales: 36 Glorious Bike Rides in Wales and the Borders for our Wayfarer Centenary Ride route. It’s route number 8. To find out more about the Rough-Stuff Fellowship, visit their website. There’s an impending book about the club, drawn from its rich and historic archives, details of which can be found here. And be sure to sign up for upcoming second issue of the Bikepacking Journal to enjoy a fantastic feature on the world’s first off-road touring club.

Note: The black and white images of Wayfarer are from the National Cycle Archive.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.