Bikes and Builders of 2024 Bespoked UK (Part 3)

In the third and final installment of our 2024 Bespoked UK coverage, we learn why ferrous steel is the most environmentally friendly bike frame material and take a look at nine more bikes and builders, including the titanium beauty awarded “Best Mountain Bike,” an interesting Pinion steel hardtail from Ted James, a 29+ ATB from Olsen, Drust’s drop-bar 29er, the mighty Titanosaur, 3D-printed bike bling, and more…

PUBLISHED Jul 9, 2024

Wrapping up our coverage of Bespoked UK 2024, held at the end of June in Manchester, England, I take you behind the curtain of seven more bikes and their builders, as well as look at a classic Curtis frame that found a new home. Plus, find some insight into why ferrous steel is more environmentally friendly than titanium or stainless steel. If you missed parts one and two, you can find them linked at the bottom of the post under Further Reading.

Craft Titanium Hardtail V1.1 link

Kent, England

On day one of the show, I ran across James and Chloe of Craft Bikes, a small frame builder from the southeast corner of the UK in Kent, England. The first thing that caught my eye in their booth was the Craft Titanium Hardtail V1.1, as James referred to it. Specifically, my eyes zeroed in on its beautiful 3D-printed headtube, straight tubing, and clean aesthetic. It looked unadorned and austere compared to many of the bikes on display at Bespoked, due in part to a lack of paint, subdued graphics, linear tubes, and inconspicuous welds.

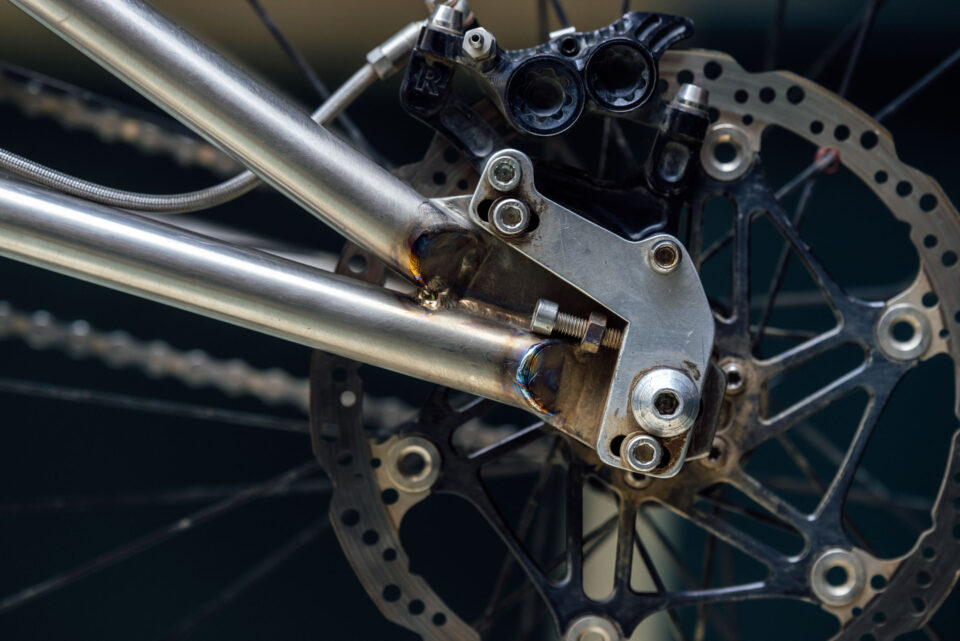

Part of what contributed to those elusive welds is Craft’s use of 3D-printed frame junctions. That included the sleek headtube, upper seat tube and seat stay junction, chainstay yoke, UDH-compatible driveside dropout, rear brake hose port, and the non-driveside rear dropout with an integrated brake caliper mount that allows a rotor up to 200mm and has replaceable bolt sleeves. Each of these parts pushes the welds outward from the junctions, which James explained moves them away from the higher-stress areas.

The Craft Titanium Hardtail V1.1 is the magnum opus of James’ frame building efforts thus far. With 25 years of metal fabrication experience, he started building bike frames in 2017. He mentioned that it was born mostly out of curiosity and desire to make something from materials he was familiar with for himself instead of clients. He started making frames from steel, and once he had a couple of years of steel frame building under his belt, he started researching methods and equipment that would allow him to work in titanium, which James admits is what drew him into making bikes in the first place.

“I knew I would need to adjust the process and increase precision and cleanliness, but titanium is next level, which probably suits my obsession with the details,” James explains, “The TIG welding process is quite different to steel, and things like back purging the frames with argon shielding gas are of vital importance… attention to detail is everything.” His description of working with titanium certainly matched the near perfection of the Hardtail V1.1 frame. He also mentioned that this level of detail made them decide to only work in Ti and not mix materials in their small shop. He also described the build process that uses some of their tooling for very tight tube mitering tolerances. I won’t go too far into it, but the level of detail in his description is reflected in the intricacy of the frame.

The Craft Titanium Hardtail V1.1 is made from straight-gauge 3-AL-2.5V (Grade 9) titanium tubing with each of the six additive parts printed from 6-AL- 4V (Grade 5) titanium. This size medium-ish bike has a nice and long backcountry trail geometry with a 1,205mm wheelbase, 60mm BB drop, 450mm reach, 75° seat tube angle, and a 65° headtube angle when measured at 20% sag with a 140mm fork. It clears tires up to 2.5″ in width, but Craft recommends 2.4″ for riding in the mud to allow plenty of room. Accent graphics are painted with Cerakote coating by JMJ Designs.

The Craft Titanium Hardtail V1.1 not only won Best Mountain Bike at the show, but it also was the co-winner of the Peers Choice award alongside Clandestine’s Pinion Carrier, which we featured in part 1 of our coverage. For more on Craft Bikes, check out their website here.

Ted James Pinion Hardtail link

Gloucester, England

The formidable Ted James, aka SuperTed, got into BMX and skateboarding when he was 14 years old and tried all forms of racing and riding in the years following. In the early 2000s, Ted found a niche within fixed-gear freestyle and was sponsored by Charge Bikes, working with brands like Vans and Fixed Magazine. The now 42-year-old Ted has been going full steam ahead ever since, and recent images capturing bearded Ted mid-air wearing bibs and Vans pretty much fit his vibe.

Like many characters in the bike business, Ted started working as a mechanic in a local bike shop. Through a few twists and turns, including an apprenticeship with Dave Yates for welding and fabrication, Ted began his life-long ramble as a frame maker. Ted started repairing steel frames by fillet-brazing on a homemade jig he cobbled together from a discarded printing press. Later, in 2008, he made his first completely self-built bike frame, a fillet-brazed fixed gear, in collaboration with Fixed Magazine for Vans shoes. Three years later, he began TIG welding, and 10 years ago, he added titanium to his repertoire, which you can see in the off-road touring bike we captured in 2018.

Ted also got into building his own tooling and machining parts along the way, which enabled him to bring some wild ideas to life, such as the 29 Gnar that he showed me a photo of, a hardtail featuring an Alfine internally geared hub built into the frame triangle. “I have tried to tame it down over the years so I can make bikes faster and maybe make some money too, but you can’t suppress the ideas for too long,” Ted told me.

The steel Pinion elevated stay hardtail I photographed has some clever and creative elements, but it’s also not too over the top, “As with most of my builds, it’s a bespoke one-off for a customer, although it’s a design I’d like to offer as a model,” Ted added. “I have one half-built for myself with a slightly different geometry, and I’m thinking about building a titanium version.” In summary, it’s a short-travel hardtail designed to work on a variety of trails and terrain but mainly to tame the trails around Gloucestershire and Wales, where the bike’s owner lives. “Tom mainly rides it on super steep technical track, hence the steep seat tube angle for going up and the slack head angle for descending,” Ted said. “But in the last six months, it’s been in the Italian Alps.” And it’s been dogpacking, as evidenced by this photo that Tom sent Ted mid-ride.

The Pinion hardtail was TIG welded from T45 tubing (similar to 4130 chromoly). “We went with a 44mm headtube for the option of running an angle-adjust headset,” Ted explained. “On mine, I went for an integrated headset design.” It has internal downtube cable routing for the rear brake and dropper seatpost that exit over the top of the gearbox to keep things tidy and provide a clean run into the seat tube for the dropper. The Pinion mounting plates allow the gearbox to slide fore and aft to tension the chain and lock into place. Another eccentricity is the elevated chainstay that offers extra mud clearance, room for up to 3.0″ tires, and the option for belt drive without a splitter in the seat stay.

When I asked Ted what other bikes he had in the works, he mentioned a stainless steel 20″ wheeled tourer with a Rohloff and Gates belt drive, and, “A design I’ve had in my head a while, which was re-ignited from the show, is merging the Pinion hardtail with the high-pivot dual-chain singlespeed downhill bike to create a low-maintenance trail/enduro bike.” As you can see in the photos above, that bike was also a sight to behold.

HEX Components link

North Yorkshire, England

Rounding the corner from Collins Bikeworks, who I wrote about in part two of this coverage, I was mesmerized by the intricate patterns and textures on display at Hex Components, a one-man brand based in North Yorkshire. Founder Ben Tew started the venture about a year ago and now makes 3D-printed top caps, seat post clamps, brake levers, and bar ends. I was pretty smitten with Ben’s creations and had to inquire further.

It seems like common story is that all the best bike gear comes from riders who apply skills and expertise they acquired elsewhere to make things they want for their bikes. That pretty well sums up the story behind Hex Components. Ben has two decades of experience in industrial design and mechanical engineering, including work in everything from experimental aircraft to high-end lighting to sustainable sneakers. Ben’s not new to bikes, either; he recalls his first mountain bike in the 1990s, a Bridgestone MB-1 that he desperately wishes he still had.

Hex started as a personal passion project. Ben had just left a design job where he was regularly using metal 3D printing, and he started making 3D-printed stainless accessories for his trail bike. The motivation was that he wanted parts that were more interesting and aesthetically pleasing than what was available, so he just made them. Ultimately, his friends took notice, and he made more to sell to them.

The process behind these components is pretty interesting. Ben usually starts by sketching ideas and patterns. “I take a lot of inspiration from patterns in nature but also mathematical patterns,” Ben describes, “I then quickly move into 3D modeling, where I like to create several early prototypes on our resin printer to see how the patterns might look.” Once he narrows down the designs, he has them made using SLM (Selective Laser Melting) metal 3D printing in both the USA and France. The stainless parts are finished elsewhere, but Ben hand-finishes the titanium parts in his North Yorkshire workshop.

Ben’s now about a year into Hex Components and has gotten serious about it over the last six months. He started with stainless and titanium top caps that were rather simple and very labor intensive to finish but has since evolved the designs into parts that can be made in small batches and finished at a much higher level. At the same time, he expanded his offerings to include bar ends and seat post collars. Find all the Hex offerings over on their website here.

Olsen Bikes Swan Pinion link

Newhaven, England

Steve Olsen is another mainstay in the UK frame building scene. Steve made his way through the industry working with several bike brands as a product designer, but he ultimately left to start his own gig and founded Olsen Bikes in 2013. He admitted part of the reason for this move was frustration that bike designs were being driven by marketing decisions and mass market drivetrains.

Influenced by UK mud and rain, Steve started developing bike designs around the Gates Carbondrive. This led onto a tensioning dropout system that works with Pinion, Rohloff, singlespeed, or a derailleur. “Most other countries have adopted the Gates and Pinion for its low maintenance and the fact that it simply keeps you going,” Steve explained. “Derailleur drivetrains are getting more fragile, especially for off-road use in the UK, where mud grit and water is always involved, plus a lot of roads are salted in the winter. We’re being pushed into an open drivetrain system, which is not really solving the biggest problem—it’s open to the elements.” Needless to say, Olsen now builds Pinion/Gates bikes almost exclusively.

This fine specimen is the Swan Pinion, which features a splatter anodizing job as a nod to Klein and a beautiful titanium fork. The Swan is named after Swan Inn in Lewes, a pub just off the South Downs Way (SDW). As a matter of fact, all Olsen bikes are named after pubs along the SDW, paying homage to the fact that they’re based in the foothills of this iconic 100-mile neolithic trade route. “The SDW will kill you on a gravel bike as the flint and chalk is the size of your fist and will give you a battering, so 50mm tyres are a minimum,” Steve described. The SDW has been the inspiration to all of Steve’s bikes.

The frame itself is TIG welded from plain-gauge titanium and has a 3D-printed chainstay and seat stay yokes, which Steve said speeds up production, is more accurate, and allows clearance for tires up to 29 x 3.0″. That beautiful titanium fork is merely a prototype, and it will be replaced on this model with a truss fork.

The other bike Olsen had on display was the CargoN. Olsen is looking to focus more and more on urban utility and mobility. He explains, “The UK Cargo Bike market is really small at the moment, however it is growing fast 30-40% each year. We have research from three universities who have worked with the public over the last few years to identify barriers to the market.” Part and parcel, Olsen started the CargoN project two years ago with weekly zoom calls to brainstorm and develop an alternative to the White Van for last-mile deliveries. Their research provided similar findings to the university research, and they combined the two to design and create a modular platform for both commercial couriers and families. “We are trying to resolve all of the barriers to market and think front loaders are the best option for all of us all transition to net-zero,” Steve added. Learn more about that here.

Drust Drop-bar 29er link

Berlin, Germany

Yes, more Drust! If you missed the beautiful Drust Cycles cargo bike in our Eurobike coverage yesterday, be sure to check that out. And for some background on Drust, you can dig into our Field Trip to their Berlin workshop to learn more about frame builder Konstantin Drust and how he got started. In a quick nutshell, he was floating around in life and ultimately washed up at Big Forest Frameworks, where took a class and got hooked. The rest is history, and a lot of exceptionally beautiful bikes have followed. When I approached Konstantin about photographing this particular bike, he modestly said he wasn’t too excited about it. However, I thought it was quite impressive and insisted.

“I guess I would call this bike a monster gravel gravel bike for rough terrain or a drop-bar touring mountain biking,” stated Drust when I asked if it had a name. “It’s a customer’s bike built for traveling on a mix of rough, loose, or sandy terrain.” It has a high stack geometry to give it a comfy perch and steering geometry designed to be ready for more easy trail riding. Bikes like the Salsa Fargo and Tumbleweed Stargazer have proven that there is a demand for bikes like this and people who prefer drop bars, but, “I don’t think this type of bike can truly replace a real mountain bike,” Konstantin added, “In the end, it’s the riders and their skills who decide what’s possible and what isn’t.”

Like almost all of Drust’s creations, it’s fillet brazed with silicone bronze using a oxyacetylene flux brazing set up using mostly mis-cut tubes from earlier mountain bike builds. It has a Reynolds 853 down tube, a Columbus Zona top tube and seat tube, and Dedacai seat and chainstays. The frame has clearance for 29 x 2.6″ tires and a 38-tooth chainring, internal dropper cable routing, and a Syntace 148 x 12 rear axle. The build sports a really nice-looking crankset from Cyber Cranks, the new Seido Boost carbon fork, and Gramm bags, complete with their new fork packs.

Unlike a lot of show bikes, this one’s powder coated instead of finished with wet paint. It has a matte rust color that keeps it pretty subdued but also looks nice in natural light. “I consider powder coating a very good alternative to wet paint,” Drust explains. “I don’t think it can replace it in terms of possibilities, but for bikes which will be well used, powder (if done right) is more durable, cheaper, and more environmental friendly.” But he also mentioned that wet paint offers way more design possibilities.

Currently, Drust has a few new bikes in the works, including working on his cargo bike. He also has a foldable/collapsible bikepacking machine and a cycle-truck in the hopper. “I enjoy building bikes that will be in regular use and not spending their life as a trophy in the garage,” Drust added. “Mainly, what I want to ride myself: bikepacking mountain bikes, utility bikes, cargo bikes, and all the weird stuff.” Find more on at DrustCycles.com, and check him out on Instagram @drustcycles.

Curve Titanosaur link

Melbourne, Australia

Our friends from Curve Cycling were also at Bespoked, which was a cool turn of events based on the final stop in their “UK Bikepacking Tour,” a ride series they put on through England throughout the month of June. It was great to catch up with Ryan, Jimmy, and Gus, and they had a few bikes on display, including a lovely Belgie road bike and the venerable and unmistakeable Titanosaur. Yeah, most of us have already seen the Curve Titanosaur online, but peeping it in person was something else. Plus, the project may have wind in its sails.

Long story short, when Curve ran the numbers on the Titanosaur project, the tooling and costs associated with it were going to require about AU$280,000 ($188,500 USD). The initial crowdfunding campaign, which we shared at the time, only got to about 30% of the target. Curve had planned on fronting 50% of the financing, but there was still uncertainty about interest from the general public. However, there’s renewed interest. As Ryan summed it up, “After five years of bringing this beautiful beast into existence, I think we just ran out of steam, but bringing it over to Europe renewed my enthusiasm, and I think a lot of the team’s enthusiasm for the project… it really captured the imagination of so many who rode it, not only tall riders but also 175-185cm extroverts!”

At this point, Curve needs about 20 confirmed sales with deposits to help complete the tooling needed for the carbon fork, as well as investment in the production run of components that turn the Titanosaur into a complete bike. Obviously, as a small brand, cash flow is king, so that’s part of the stumbling block.

This particular demo model or prototype is essentially a 56cm frame designed for its creator, Dr. Jesse Carlsson (Ph.D. theoretical physics and ultra-endurance phenom), “Don’t tell him I said that. He’s a humble guy but should be celebrated for his contribution to cycling and especially adventure cycling,” Ryan added. “Although, we do have a range of sizes modeled from medium, which would suit a rider from 175cm, all the way up to a XXXL, which would work for a 225cm rider.”

Another hurdle is tires. Most of the tires they’ve tested are good but very heavy at 1.2 kilograms a piece. “I think our dream tire would be anything that resembles a modern gravel or mountain bike tire. The ones that are currently in existence are for unicycles, and the technology there unfortunately isn’t in the same league as what we’ve come to enjoy with modern tubeless tyre technology,” Ryan explained.

Other than the Titanosaur, Curve has a lot going on, including a redesigned Uprock hardtail with sliding dropouts, an update to the Kevin gravel bike, and several expeditions. They’ll be in South Africa, Mongolia, and then Argentina in February 2025. Check out CurveCycling.com to stay in the loop.

Curtis Bikes Singlespeed link

Somerset, England

Curtis Bikes has been around for a while. Brian Curtis started hand brazing at age 17, and in 1972 at age 31, he was making motorbike frames under the brand Curtis Bikes. He’s been the head brazer for Curtis ever since. Gary Woodhouse came on board in ’79 and persuaded Brian to start making BMX frames as the sport was on the rise. That changed everything and the company pivoted entirely to bicycles. Gary took over the company in ’96, but Brian remained the head brazer. Today, all Curtis frames are made by Gary and Brian using hand cut and shaped tubing, tacked together in a jig, and fillet-brazed by Brian himself. In fact, to this day, every Curtis frame in existence has been brazed by Brian.

I wasn’t sure what the origin of this particular bike was, but I knew I wanted to photograph it when I saw it in the Reynolds booth. The upside down 13 and singlespeed champs shingle was another motivating factor. But truly, those beautifully slim 853 tubes and visible fillet brazing reeled me in. After shooting it, I reached out to the owner Jim Davage to learn more. Jim is a postman and bike mechanic in Somerset who’s been riding for Curtis since the late 90s. This particular frame wasn’t made for Jim, but as he explained, “This early model frame was on the wall in the Curtis workshop for years, and after looking at it for all that time, I asked Gary if I could have it. Luckily for me, he said yes.”

The frame is actually eight or nine years old, but it certainly doesn’t look like it. Jim’s only had is set up as a singlespeed, “I love the simplicity of it… no frills or gimmicks. It’s my go to bike if I want to just go straight out the door and go for a blast, just get on and ride.” Jim’s never raced it, but said he’s, “Very tempted to ride the singlespeed champs though, just for a laugh.”

Steel is Real (by Reynolds) link

Birmingham, England

Another highlight of Bespoked UK for me was the Talks series lecture by Reynolds General Manager, Martin Shepherd. Martin started this presentation with a history of Reynolds, highlighting how steel fell by the wayside when aluminum and carbon overtook the bike world, and how steel is seeing a resurgence. He then went on to provide a brief history of steel, what makes it special, and how it’s a unique material that can be melted down, endlessly recycled, and made into something else time and again, suggesting that your bike might contain steel once used in an ancient Roman dagger. He then went on to talk about Reynolds’ different tubing types, and the properties each one has. All this was fascinating, but it was their environmental study that I found particularly interesting.

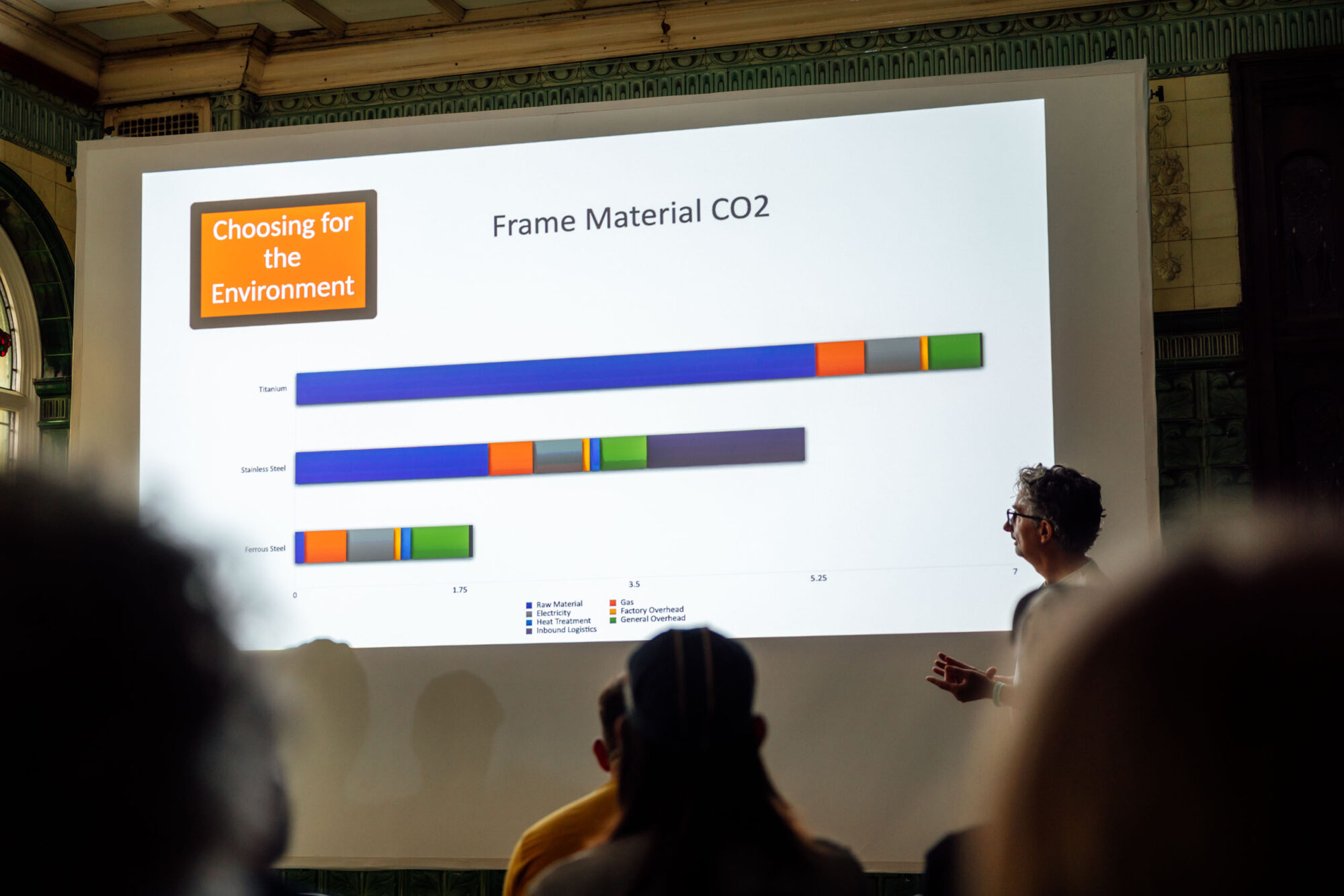

In summary, Reynolds carried out an internal study to assess their carbon footprint and how they could reduce it. In doing so, they also gathered metrics on the different frame tubing they produce to determine how much CO2 is created during the full manufacturing process, including raw material production, inbound logistics, gas and power used during production, and other forms of overhead.

As you can can see in the slide above, ferrous steel (such as Reynolds 525, 725, 853, and 631) is hands down the most environmentally friendly material based on this study, proving to have less of a carbon footprint than their stainless or titanium. The numbers at the bottom of the chart are kilograms of CO2 per frame tube: 1.9kg for ferrous steel, 5.1kg for stainless, and 6.75 for titanium. To put this in terms we could all understand, the final slide compared those emissions to driving a common British automobile: Making the tubes for a single steel frame creates the same amount of CO2 as driving a Range Rover just 32 miles.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.