Baja Divide Pt. 2: Lessons from the Cacti

In his second dispatch from the Baja Divide, Evan Christenson peels back the layers and shares more about an unexpected mix of locals and fellow bikepackers he met on his ride across Mexico’s Baja California peninsula. Read their stories and join Evan in unpacking some of the lessons he’s learned here, paired with stunning photographs…

PUBLISHED Apr 13, 2023

Tuly’s courtyard is a hard place to sleep. Trucks careen through the small backstreets in the outskirts of La Paz, a dizzying blur of mariachi music and Spanish on the loudspeaker and two barking dogs in tow. The wind blows off the sea and through the gate, whistling and howling and stirring up the thick coat of dust covering the walls. The cement ground is hard, the lighting is cold, and the new puppy shits on my stuff twice. The sliding glass door is a vending machine of humanity. People are in and out of the house all day. Tuly herself, an old friend, and the sailor who’s been in the guest room for four months. And then there’s us, the 750 cyclists who have rolled up and called her small courtyard home in the past couple of years. It seems what started as a nice gesture has started to run away.

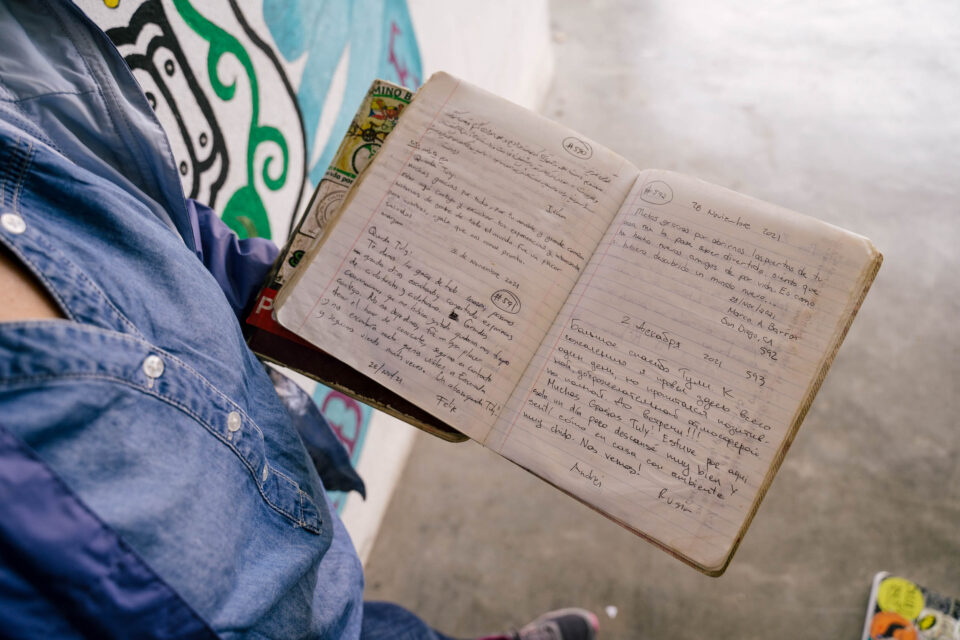

Tuly shows me her guestbooks, now three in total, that are full of stickers and stories and Instagram handles and endless thank yous. She remembers the first guests so clearly, but the middle years have become a bit of a blur. It all started eight years ago when her husband at the time met a bike touring family in Loreto. They exchanged contacts, and when the family arrived in La Paz, one of the kids was sick. They needed a place to rest, and Tuly invited them in. A few weeks later, another touring family heard about Tuly and stayed as well. The numbers slowly rose as the tourers began to whisper among themselves, and it was put on Warmshowers two years later. I sign her book as number 714 on my way in, and know this small house in the outskirts of La Paz is packed full of stories.

Tuly laughs as she flips through the guest book. “Oh man, this guy smelled so bad! And these people were so nice, they made the best food. Oh, and this guy made his own bamboo bike!” Tuly has seen it all by now: dogs and cats on bikes, handcycles, recumbents, unicycles, doctors, YouTubers, musicians, and artists. People from Korea and Japan and South Africa and the Middle East. Tons of Europeans. People with brain tumors and people riding around the world only eating protein powder.

The past few years, as the Baja Divide has grown more popular, she’s seen more bikepackers and says most of her guests now are on mountain bikes. Tuly’s an active person. She goes to regular kayak classes, hikes in the mountains, and rides her mountain bike and road bike. She’s out for some sport every day. I ask her if all these people inspire her to get out and tour the world, as she hasn’t traveled all that much. She laughs again. “Not at all.” Why go see the world, when it comes to her?

With her small courtyard and big heart, Tuly has learned so much from the riders who stay here. She’s learned English to better communicate with them and says she’s the only one of her friends who knows where Kyrgyzstan is. We sit around the table late one night sharing food: Tuly from Mexico, Tim from Japan, two Spaniards, a Canadian, and a Swiss rider. So much of the world has been seen among the seven of us. The conversation is a dizzying mix of Spanish and English and French and all sorts of accents and experiences. It feels like the world is tiny in these moments—like it can all be held and peeled apart like an orange. We all instantly connect over our love for bikes, and we sit there and cut into each other’s lives. Everyone carries their own knives of perspective, and the fruit is familiar and sweet. Tuly’s house is full of this nectar of the world, and it soothes my tired bones after another hard night on the concrete.

Before I leave town, I’m told I need to go meet Jackson, and I’m warned that he’s an interesting character. “I think he actually likes the solitude,” another bikepacker says. We go for fish tacos in town, and before we can order, I’m already racing to scratch down notes in my journal. Jackson does like the solitude of the desert. I quickly learn why.

Jackson is a dyed-in-the-wool Canadian, a real Kootenays guy, a plaid flannel, maple leaves and moose antlers, red and white Canuck there, eh? He comes from suburban Vancouver. His dad is a software salesman, and his mom is a receptionist. It was all straight and narrow, but Jackson had an itch to see more. He graduated from high school and went to South East Asia. He liked the independence, the newness, the vibrant colors often missing from Canada in the winter. So, he returned again soon after.

Jackson learned he liked traveling, so he went down to Nicaragua and backpacked to Peru, inlcuding a two-month stint living on a barge on the Amazon River. He went home to work on a farm for a bit, and when the itch returned, he went to Rwanda and hitchhiked around Africa. He went through Congo and Kenya and Uganda and Ethiopia, all the way up to Israel.

Now, a few years later, we sit in Baja after he’s just finished the Baja Divide. He sips his beer, and I wonder how it all connects. How do you get from the suburbs to Congo to the Baja Divide? He met no other travelers while in Africa, just a few bikepackers in Rwanda on the Congo Nile Trail. His journey was long. The hitchhiking offered a unique but often boring perspective, and it offered plenty of time to reflect. “My ass was shaped like an African bus seat, and I was like, ‘There’s gotta be a better way to do this.’ And so I bought this bike…”

He bought a Salsa Vaya, and with no knowledge of how to fix it or pack it (or really even ride it), he flew out to Turkey to try bike touring. He started with a set of clipless pedals and rode in Vans, because he didn’t know what the weird pedals even were for. He rode to Spain, where he ferried to Morocco, rode into the Atlas Mountains, then pushed south into Western Sahara and on into Mauritania. He rode for nine months before settling into Dakar just as the pandemic wrestled its grip on the globe.

He had a botfly removed with gasoline the day before his repatriation flight, and landed in Canada embedded with a nasty tick-borne illness. He shows me photos from riding across the Sahara with the Atlantic Ocean on one side and an ocean of sand on the other. It reminds me of a Baja Peninsula from a different planet. Jackson tells stories all day: of the barge almost sinking in the Amazon, of breaking his bike while hitchhiking the iron ore train from Nouadibhou, of months immersed in small villages in Uganda, and I can’t help but feel pedestrian as I have to explain Minecraft, the game the kid next to us is playing at dinner. Jackson is the type of guy I feel obliged to ask not if but when was his last fight. And he’s the type of person I’m not surprised by when he casually responds with, “Oh yeah there eh, had a big Donnybrook a few months ago at the bar.”

To Jackson, the Baja Divide is all new. He had never followed a GPX track before. Never ridden with other people. Although he set out alone, he and Brian Charette rode together for weeks out in the desert. He’s always been a traveler first, and even when riding across the Sahara, he saw the bike as secondary to his priorities. But here, the bike came first because the distance between resupply, the lack of water, and the desire to finish all push the riders along the route. To him, the Divide was a new exercise in traveling, of putting the bike first and the traveling second. He said it was hard but worth the pain for the beautiful and interesting things in the middle.

Jackson still rides in Vans and cut-off jeans and on the skinniest tires here because they’re what he already had and good enough for him. He’s not here to break records, he’s here to see another unique part of the world. One morning, he woke up with a rattlesnake in his vestibule. He also cheered on the episode of Brian shooting tequila from his alcohol burner. He decides to come to stay at Tuly’s on my final night, and we go get drunk and end up the only gringos at a carambole bar.

I’ve been wondering all along how the changes of the Baja Divide have changed the experience—if it still constitutes an “adventure.” I feel elitist for even wondering, but with Jackson, I feel free to ponder it. I pose the question to him, a guy with adventures so wild under his belt I feel like he’s qualified to answer anything. He leans back in his chair. “You wake up having no idea what’s gonna happen. To me, that’s a real adventure.”

Back from the bar that night, he pulls out the foam pad and lies straight down on the concrete of Tuly’s courtyard. “Are you really going to sleep on just that?” I ask, the ground still spinning, the courtyard a mess of snoring cyclists. Jackson pulls out another beer and cracks it open, and I fall asleep. In the morning, I pack up my things and roll out with a throbbing head and no idea what’s going to happen next.

I ride north, still unsure of what will happen next. Two days later, I find myself on a fishing boat all day, from 5 a.m. to 6 p.m., learning Spanish curse words and wrangling yellowtail. I come off the boat, and the ground is still swaying under my feet when I run into Niels and Stephanie, and we all stand there bewildered and shocked, them from the grueling descent out of the mountains and me from watching fish get murdered all day. The fish are brought over and fileted, and we eat fresh sashimi on the beach and fall into a two-day-long conversation, lulled into a trance by the gentle rocking of sailboats in the bay and the endearingly calm happenings of a small, remote fishing village.

We’re talking about the Divide when a group enters the restaurant and starts asking about our trip. We all hang out for a while. The old man in the center walks around with an entourage and turns out to be one of the founding members of Burning Man. He’s down here buying a house, and proudly shows off photos of his more recent art projects, the last one being a giant recycled mermaid for the Duke and Dutchess of Edinburgh. He goes by Flash, and we fact-check his stories later that night and are shocked to find it all true. Here he is now, looking back at a wild life defined by the desert. He’s not retiring in the same desert of Burning Man but in the desert of Baja, in a small town of just 100 fishermen. He says Burning Man has long changed from what he originally envisioned. Baja is peaceful, and a fresh start for him. In one of his magazine interviews, I find a quote that explains it all: “We were all raised to believe in freedom. Well, where is it? It’s not in your car payment. It’s not in the cubicle you sit in. The desert brought it. That vastness creates freedom when you see that absolute blankness. It’s a beautiful place.”

Niels and Stephanie are down here on their honeymoon. They got married during COVID back home in Belgium and set out on a world tour by bike to celebrate their love, shake things up, raise money to donate to charity, and inspire others to travel more sustainably. Niels has been a traveler for decades now, backpacking around South America in his 20s to figure himself out and pushing on into South East Asia to see more. He took his knowledge of traveling to work in an office in Ghent as a travel agent. He’d build itineraries for travelers, mostly young people, to go out and experience the world. It was a rewarding job. His office was full of postcards from his clients, and he felt like he really helped people get outside of their comfort zones and understand the world a bit more. But what started as a fun job with great coworkers changed as social media began to reshape the travel industry.

In a town barely on any map, Niels sits next to the sea with his beer and sashimi and recounts how people started to come into his office with a picture on Instagram and say how they just wanted to go there. And they wanted it done faster and easier. He grew disenchanted with the industry and wanted to just travel instead. He married Stephanie, and they quit their jobs and sold everything and bought touring bikes and left. They look back amazed at how long the journey feels already. “We bought the bikes in Bruges, and tried to ride back to Ghent, you know, only like 50 kilometers, and after only 30, we stopped and booked a bed and breakfast! It was soooo hard back then.”

The new couple pushed on, though, and they rode across Europe and through the Faroe Islands and around Iceland and down the Great Divide. They put on bigger tires and mailed stuff home and set out on the Baja Divide to carry on south. They’re not the only tourers I’ve met incorporating the Divide into a Pan-American trip. In fact, this year, about half the people doing the full Baja Divide are planning on riding all the way to Argentina. For Niels and Stephanie, it’s been a lot to handle, though.

The “Just Married” sign on the back of their bikes attracts a lot of attention; sometimes, they’d get eight people talking to them at grocery stores in California. And for Stephanie, who’s never been a cyclist before, the difficulty of the Divide has worn her down. Stephanie says the hike-a-bike sections of the route are her favorite, because she doesn’t really like riding the bike. Stephanie is the only person who hesitates when I ask if they’re glad they did the Divide. Still, to them, traveling by bike is the best way to do it. Niels says he’s learned more about Stephanie on this trip alone than in the six years they were together before it. And for all the hard days and low points, it all feels worth it. Niels looks back on his early days of traveling and admits how different this is. He says there’s more satisfaction in doing it all yourself. “I wish I had the guts to do this when I was younger. You learn a lot more doing this than sticking to the main routes—the stuff I used to sell as a travel agent.”

I push on and ride north, slogging and swearing up the climb that left Niels and Stephanie in shock. I finally leave the coast and enter the canyons, the lower half of the Missions section that’s becoming known as the most beautiful. It’s stunning riding, green and lush after a heavy season of rain, and I start to play telephone with the riders heading south. I hear who’s coming next, who’s ridden with who, and what they’re like. Everyone gets a tagline. There’s Matt and Claire, the chefs. Alan and Jo, the Kiwis. Me with the broken bike. Mike and Eric with too much stuff. And Sylvan the kid.

We all follow the same GPX file, and I wonder if this will ever become one of those main routes Niels grew so disenchanted by. It feels ironic to cheer the freedom of the bicycle and then line up on a predefined route. But everyone takes this same GPX file and fills it with endless unique stories. This file and guidebook have become not dogma but an open-ended gesture. Everyone picks and chooses certain sections, and only a few ride the whole thing. People venture off and explore other places and come back to the route as they feel. There’s no badge and no logbook to record who’s finished the Baja Divide. There’s no criteria to fulfill, no sign to take a picture in front of, no time to finish under. Each rider starts somewhere near Mexico and ends whenever they please. Whatever unexpected things happen in the middle is why we have all come down here.

I yell back to Megan as we ride through the dump. They’re smiling too much, laughing at me blindly shooting photos, and I’m worried about all the flies that’ll land in their mouth. I’ve decided to turn around with Megan and their partner Amy for a day, to listen to a few more of their stories, and we all brave the infamous smoking landfill together.

We met at the hotel in Ciudad Constitution, along with six other bikepackers, and Amy entertained us all as we went out to dinner that night. They tell hilarious stories one after the other, from their year living in Mexico, to their work back home in Brooklyn, and from this incredible ride they’ve had down the peninsula. The two of them work for Outward Bound, a program focused on getting inner-city kids into nature and out camping for the first time. For them, the outdoors is a place to build community, and they’ve taken that mindset down to Baja.

Amy is the most active member of the WhatsApp group chat, sending thorough updates on the sections and describing to the riders behind what’s coming up. Along the way, they’ve hung out in ranchos and watched Mexican soap operas in old car seat couches. They helped an old rancher with his solar panels and were gifted a piece of an asteroid in return, and they gave me a pair of socks to carry north to give to him as a gift. They help put the local bike shop on Google Maps, and they carry with them a beautiful handmade knife set from an artisan up north and handmade leather belts given to them as gifts. They’re down here hanging out with the people on the route and seem perfectly content slowly rolling through the rough bits.

Amy isn’t new to touring, but this is their first bikepacking trip. Amy started touring on a ride from Vancouver to Tijuana and met a group of musicians riding around the US performing concerts solely on human-powered electricity. They say that’s where their inspiration for this sort of slow touring comes from. They would all ride together and stop in the middle of the day by the river and have a picnic and swim for an hour. Amy fell in love with the change of pace and freedom.

Amy grew up closeted in the Midwest and finally felt freedom while riding the bike. Now, somewhere in their transition, Amy washes down their testosterone pills with canned cream and coffee around our morning fire. Amy and Megan have come down here to find that feeling of freedom again and to explore themselves and each other within the enveloping vastness of Baja. Amy talks of starting their own outdoor counseling company and says with a big smile how they would love to bring kids down to Baja.

I ride back through the dump a fourth time, this time with the extra pair of socks for the rancher up north. I drop them off two days later and push on deeper into the canyons. The rivers are flowing this year, there’s groundwater to filter and plenty to swim in. I ride slow and soak in the daytime and stumble into another ranch at dusk. A family sits silhouetted around their dinner table, and I ask for a place to camp. I enter for the night and stay for a week, fascinated by the intricate palapas, the hand-woven ropes, the layered mesas in the distance, and the swimming hole just around the corner. I stay with the family, and we go hunting, play cards, work the fields, eat, and siesta. The world slows down in this canyon without internet, and it’s there, while out pushing a wheelbarrow full of firewood, I run into Aly. She’s riding alone with her earbuds in and turns the corner and is shocked to see me standing there. I come to learn she’s shocked to be seeing at all.

Aly was diagnosed with Retinitis Pigmentosa two years ago. The disease is slowly eating away the rods in her eyes, and it will soon make her blind. It’s genetic, and if she’s like her great-grandmother, she’ll be fully blind by 40. She’s already down to about 30% of the average field of vision, and at night it’s almost nothing. Aly has always been outdoorsy and has traveled solo to the other side of the world, but she’s been hesitant to take on that big adventure of her life. The diagnosis has changed everything.

“One doctor told me to start making preparations for being blind. But I thought, Fuck that!” Aly has always wanted to set out around the world, but her more recent plans were interrupted by COVID. She stayed home and prepared for this trip and was diagnosed just a few weeks before leaving. But, this time, Aly won’t be stopped. She set out to hike the CDT, where she met her new partner, and now she’s here with her sights set on riding to Argentina as well.

Aly can no longer legally drive in Canada, but she rides with confidence as we roll out of the ranch and through the deep river crossings. I hold my hand out next to her as we ride, asking if she can see it, and she says no. I ask if she can see the cacti on the roadside as we pedal along, and she says sort of, but only if she turns her head. She says it’s made her slow down and take breaks, literally to just look around. Aly rides with a set of watercolors and a clunky DSLR camera, and she excitedly takes photos and paints the river where we swim. She’s feverishly documenting the beautiful things around her while she still can. Because of it, she’s more attuned to the wonders of the desert than most I’ve met. Her sketchbook is full of proof.

We sit in the sun, soaking up the warmth radiating from the rocks above the river as Aly paints. I look around while she tells me all this, and I can’t help but cry. This place is full of sharp things and rocks and cacti and broken glass. Baja is hell for a blind person. But to us, to everyone who has ridden the Divide, Baja is a land of wonder. We have seen the flowering ocotillo, the fascinating boojum, the magnificent cardón, and we have learned that sharp things can be beautiful too. I cry thinking how unfair that duality is and how what I’ve seen has defined me as a human.

I wipe away my tears and walk over to see Aly’s progress. She moves the cacti around a bit on her painting, deletes a few shrubs, omits the wasp nest. The water is a crystal blue, not the murky green mystery that clings to my legs. It’s a perfect rendering of the near-perfect world we’ve stumbled into together. We sit there, and I feel angry for Aly. She says she’s passed the anger and hedging toward acceptance and understands that this is just life.

When the clouds break, the sun crashes in with intensity, and I jump back in the water. I swim to the bottom, and I open my eyes. It’s murky, dark, and I can barely see anything. I feel around for the boulders and look up at the rays of light dancing in the ripples. I can see Aly sitting there, alone in the middle of Baja, and it all feels so wrong.

I ride north, slower now, admiring the cacti. I suppose I do it for those who can’t.

Related Content

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.