Sage, Cenotes, and an Ek Balam Jungle Adventure

Share This

Picture a pancake-flat world where $250 cargo trikes and BMX bikes with child seats rule the land. A place where a watery maze of underground rivers course below an extensive network of bike paths. Cass and Sage head out on a jungle adventure across Mexico’s version of the Netherlands, complete with Mayan ruins and magical sinkholes…

At the beginning of this year, I wrote about a Mexican beach overnighter I enjoyed with my son, Sage, who I hadn’t been able to see for a number of months for COVID-19-related reasons.

At the ripe old age of eight, Sage clearly recognises my obsession with bikes in all their forms, to the point that he loves to joke about how I talk of little else. But still, I try my best not to be a pushing father when it comes to cycling together, so I was especially happy that he readily agreed to another microadventure before we went our separate ways again.

Just to recap: The overdeveloped Riviera Maya where we met up – on Mexico’s northeastern Yucatán Peninsula – can hardly claim to be a bike-friendly region. Fast traffic pounds up and down the Caribbean coast, much of which shuttles tourists to their all-inclusive resorts. Even a ride to the beach can be disappointing, as the best stretches have been usurped by a barricade of fancy hotels. Thankfully, cyclists need only to turn their handlebars inland to discover a different side to the Yucatán so popular in tourist brochures and Instagram feeds. This is especially the case in the town of Valladolid, just an hour’s bus ride away from the coast, where a network of separated bike paths connects one village to the next. Together with all manner of rocky dirt roads and overgrown jungle trails, it’s possible to create a number of almost traffic-free, family-friendly rides, far removed from the hustle and bustle of the coast.

Now, I wouldn’t normally rate the Yucatán as a cycling destination, largely because I’ve never considered myself a fan of pancake-flat terrain. But when it comes to family bikepacking, a lack of undulation has a real appeal. For one, it’s easier on little legs; aside from the occasional bridge over the highways, the biggest elevation gain in the Yucatán comes from the medley of topes – speedbumps – so beloved by Mexican town planners. Flat terrain invariably brings more cyclists – when it comes to finding a place on the road as a young rider, there’s safety in numbers, as well as a resulting increased awareness and courtesy from drivers.

Take Valladolid for example, known for its palette of colourful, colonial houses and its laid-back pace of life. Not only are the streets busy with fellow cyclists, but you can expect to see pedal-powered machines of all shapes and sizes; one, two, three, even a family of four on the same contraption. In fact, inland Yucatán teems with cargo trikes, old mountain bikes, and ancient single speeds. Like a bird spotter in paradise, I took delight in recording the rich variety of conveyances all around. I saw homemade wooden child seats on BMX bikes, a man with a gas tank balanced on a rear rack, and my personal favourite: a father cycling the family cargo trike to church on Sunday, in which sat his wife, mother, and son, dog skipping along beside them. Yes, bike culture in inland Yucatán is as vibrant as I’ve seen it anywhere. Think the Netherlands. In Mexico. With a Mayan twist.

But back to our trip. Generally, I trawl the internet for gpx files and put my own routes together, based upon the experiences of local riders teamed with findings from satellite imagery. However, nothing beats a good local guide and my web wanderings led me to a small business called Bikers Zací – a name that harks back to the Mayan settlement that preceded Valladolid, before it was founded in 1543. The company’s intentions appealed to me immediately: using bikes as a means of exploring the local land in a more intimate way than the region’s typical tour bus tourism, with emphasis on al senderismo rural, or rural singletrack. Before long, we had a family ride lined up at 8 a.m. on New Year’s Day. Temperatures were taken and masks donned, as Daniel and his partner Abril – both local to the peninsula – led the three of us on a 45km backcountry loop. Much to both Sage’s delight, it included two extended pit stops in icy cold water holes to cool off. To those unfamiliar with the pleasures of a Mexican cenote, the secret sauce that makes the Yucatán such a fantastic family destination.

Part of a subterranean, watery maze of caves and limestone wormholes that have provided life to this peninsula since time immemorial – and above which the Mayan civilisation thrived – cenotes help temper the stiflingly hot Yucatán air, turning otherwise uncomfortable bike rides into magical, wondrous, unique experiences – and far more special than any of the water parks along the coast.

This is because each cenote is different from the next. As we racked up visits, we kept a tally of all our favourites and ranked them daily. Some required steep and slippery descents into darkened caves, where bats circled above our heads. Others were grand, amphitheatre-like, open-air affairs, with thick jungle tendrils to swim around and gaze up at. There are cenotes where stalactite tips dripped from limestone ceilings and others where stalagmites prod out of the water from below. There are developed cenotes with boardwalks and rope swings – great for family fun – and others that are accessed by rickety ladders descending directly beneath someone’s backyard.

Abril told us how the Maya held these giant sinkholes in the highest esteem, both as holy sites and as portals to communicate with the gods. And, as there are no overland rivers on the peninsula, they were used to bathe in too. Apparently the invading Spanish – arriving in an era where Europeans were hardly known for their personal hygiene – couldn’t fathom how clean everyone seemed to be.

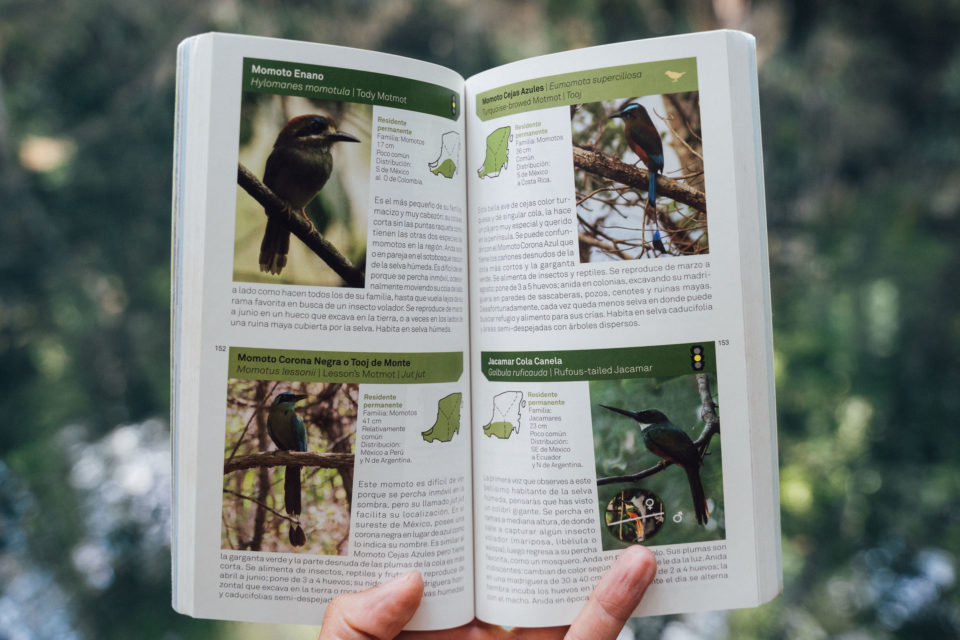

Amongst other stories, they also told us about the flora and fauna that we came across – like the cantankerous Yucatán jay that warned its band of our arrival. They taught us Mayan history and traditions – like the thatch dwellings that have rounded edges, so bad spirits can’t lurk in the corners. And they introduced us to all manner of local tracks and trails. These included caminos blancos, which Mayans coated with white gravel to reflect the moonlight, making them easier to travel at night. In fact, we had such a good time that we booked a second trip for a few days later, giving me the opportunity to whisk Sage away on a father and son overnighter in between.

Whilst it was a particular beach that we rode to on our last adventure together, here we set our sights on a Mayan ruin – the archaeological complex of Ek Balam. As any parent will know, non-cycling activities go hand-in-hand with bike rides, so the fact that there was both a cool cenote to plunge into at our destination and 30-metre pyramid to ascend sealed the deal.

And just like our last overnighter together, it was a fabulous trip that showed us a completely different side to this peninsula. We connected caminos blancos with low-traffic rural roads. We bushwacked through overgrown trails. And we set aside time to practise with the slingshot along the way. Between villages, we barely saw a soul. When Sage was closing the gate across agricultural singletrack, we crossed paths with a man in wellingtons, returning from his fields on a beaten-up single speed without brakes. A rifle was slung over his shoulder and machete dangled from a belt. After a short chat about the route ahead, he gifted Sage a freshly dug-up jicama from his satchel and went on his way. We read stories that night and peeked at the stars that glinted through the jungle canopy, listening to a hundred piece orchestra of insects. And come morning, to an alarm clock of particlarly articulate birds, we got up extra early to be the very first to visit Ek Balam and learn about the history there.

Well, learn as best we could. Deciphering the intricacies of this archaeological site is tricky, so I’d downloaded the history of the area on my phone, which we read when we were at the top of the main pyramid, under which King Ukit Kan Laek Tok is buried. The views over the jungle were glorious and its Jaguar Altar – complete with an enormous set of teeth – was a particular hit with Sage. Hashtag bikepackschooling? Later, a few tour groups arrived, so we lingered in the shadows to hear insightful snippets from their guides. And to round off the visit, we grabbed a plateful of tacos in the car park before heading back out into the heat.

Then we rode back to Valladolid again, with juice box breaks and coconuts stops en route. It was an 80km round trip with just a few hundred metres of ascent, the most noted being a mighty climb that reached a whole 40m above sea level! And I’m not ashamed to say that I enjoyed every moment of it. Well, almost. As we only had one air mattress between us, I drew for short straw and curled up on a small seat mat. It may not have been my most restful night’s camping in my life but it was an easy sacrifice to make – anything to encourage more experiences like this with my son.

And as for those fantastic yellow trikes that we saw both in towns and on all the bumpy jungle tracks in between, they deserve special mention. Not only are they omnipresent throughout the Yucatán, but they’re ridden by men, women, and children alike. They cost 5,500 Mexican pesos, which is a little over 250 US dollars. And no, I’m not going to tell you what our Big Rig would set you back…

The Big Rig

In the last post, I mentioned how Sage left his solo bike at home and brought the tag-along instead, as we weren’t really sure what kind of road conditions we could expect in Mexico. Although he’s now largely outgrown “the big rig,” it was nigh on perfect for the trip. It allowed us to tackle unfamiliar trails that were often rocky and rooty, and cross occasional highways safely if needed. Aside from our overnighter, we used it on a number of day rides around Valladolid, as well as our guided trail rides that were often rooty and rocky. You can read more about this particular model – the Tour Terrain Streamliner – and why I like trailer bikes in general for these kinds of family trips, in the Bikepacking with a Trailer: Complete List and Guide. Or, read the box out at the bottom of the New Year Biosphere campout post too.

The route

If you happen to find yourself in the Mexican Yucatan, with or without a family, I can highly recommend heading out for a guided ride with Bikers Zací or through their Instagram. Daniel and Abril know the trails inside out and can take you to all kinds of ‘locals only’ spots. There’s lots of great singletrack to enjoy.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.