The Fight for Summit Road

Summit Road is a stunning 20-mile stretch of gravel that snakes its way through California’s Santa Cruz Mountains, but almost half of it is illegally guarded by metal gates and misleading “no trespassing” signs. In this essay, Aaron Rickel writes about the fight to keep Summit Road public, and the lessons it offers to all public lands users…

PUBLISHED Feb 20, 2020

Words and photos by Aaron Rickel (@ajrickel)

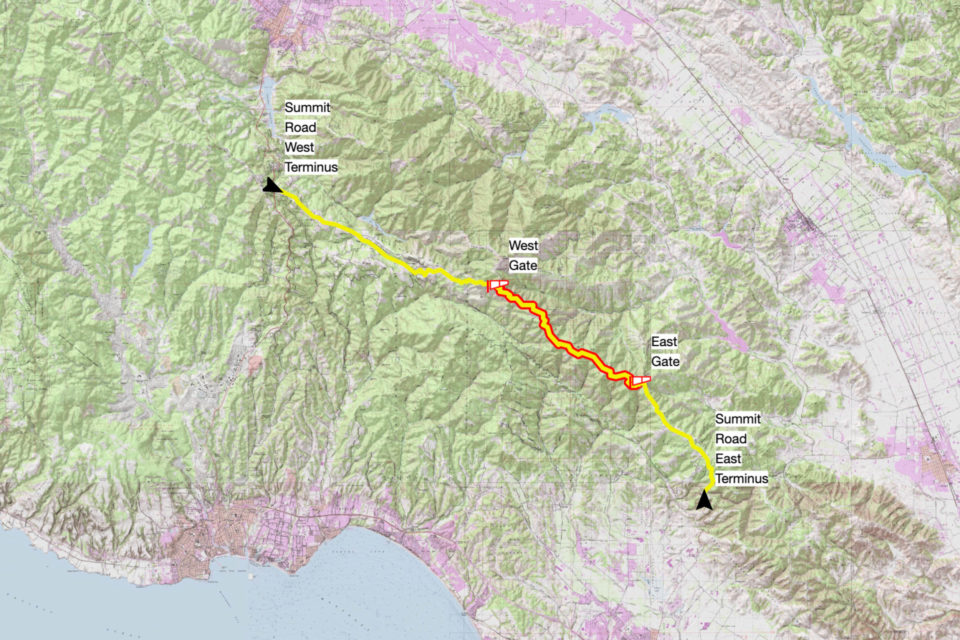

Summit Road is a stunning stretch of single lane gravel that winds 20 miles along the crest of the Santa Cruz Mountains in Northern California. Riding the border between Santa Clara and Santa Cruz Counties, it snakes through towering redwoods, oak groves, and sagebrush covered hills. Where the trees thin higher up, a clear day reveals sweeping views of Monterey Bay to the south, San Francisco Bay to the north, and thousands of miles of Pacific Ocean to the west.

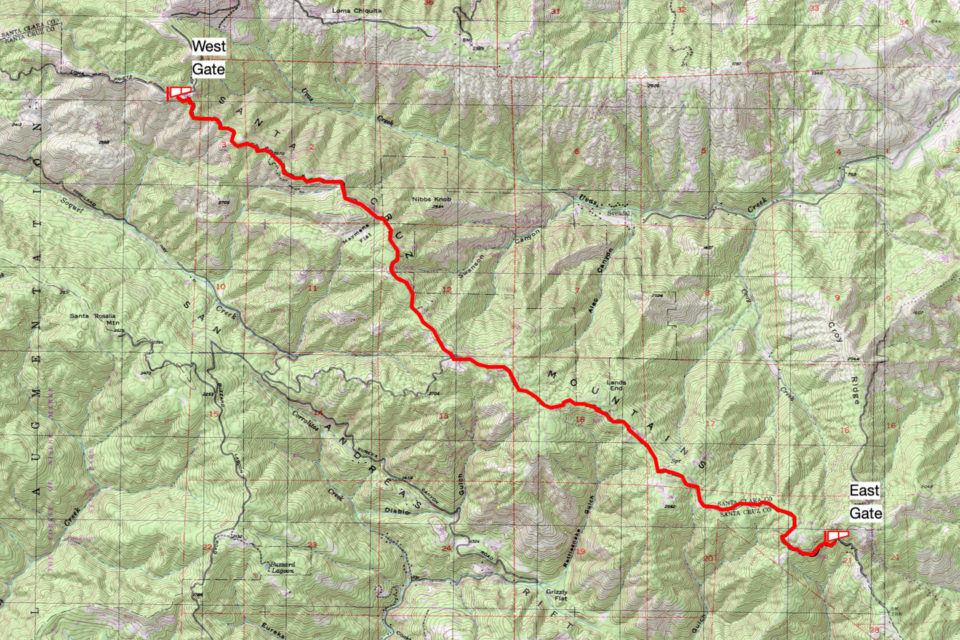

Summit is a cycling artery that connects small coastal cities to Silicon Valley and the greater Bay Area. It’s the kind of route gravel cyclists dream about, so it’s nothing less than a tragedy that eight crucial miles through the heart of the road are illegally guarded on either end by metal gates and “no trespassing” signs.

Background

This wasn’t always the case. In the 1930s, the California Department of Forestry (CDF) constructed Summit Road for fire service access. In the early 70s, however, the CDF stopped maintaining the road, leaving residents—as you can well imagine—pretty upset. One landowner in particular, Ray Strong, “exhausted all avenues in an effort to find a county, state, forest service, fire district or any other agency that would accept any responsibility whatsoever for improving the road.” But nobody was stepping up.

The condition of Summit Road continued to worsen, exacerbated by four wheelers and dirt bikes ripping through on unsanctioned weekend races. And so, on April 7th, 1979, Strong took matters into his own hands and installed a gate at the west end of Summit Road. Later that month, he and fellow resident Tom Lyons formed the Summit Road Association (SRA), an organization that collected money from residents to maintain the road.

The SRA was intent on keeping people out who were flagrantly tearing up the road, evidenced by a second gate erected at the east end of Summit Road two months later. Other than the residents who purchased keys from the SRA, Summit Road was officially cut off from the outside world.

Santa Cruz County, however, wasn’t thrilled with the show of independence. They demanded the gates be removed, insisting the SRA never had the right to install them in the first place. Residents fired back, saying they would remove the gates if the county would maintain the road. This dispute lasted over a decade until, in October of 1990, the SRA agreed to remove the west gate in exchange for much-needed maintenance paid for by Santa Cruz County.

The armistice was short lived. In the summer of 1994, the SRA reinstalled the west gate at a slightly different location, sparking frustration from hikers, cyclists, and motorcyclists who had enjoyed the road for decades. Still, no group of recreational road users had the political clout to change anything about the situation.

The real war began in 1998, when locked gates on Summit Road blocked truck drivers for Redwood Empire, a logging company in the area. A group of residents, led by Kathy Dean, sued Redwood Empire, saying Redwood Empire had no right to be using their private road at all—and especially for business purposes. Redwood Empire filed suit the same day, claiming the road was—and had always been—public, and the case went to court.

In Good Company

Fighting over rights of passage isn’t a new or rare story. A case in Topanga Canyon, just outside Los Angeles, had lawyers referencing dozens of maps and surveys from as early as 1895 to determine when, or whether, a public right of way had been established. The complex court case eventually decided that the road in question had in fact been originally designated a public street, much to other residents’ relief.

Unfortunately, not all fights go the public’s way. Bear Gulch Road, also in the Santa Cruz Mountains, was originally constructed as a public road in the mid 1800s to provide access for logging. Yet in 1976, after years of taxpayer backlash over maintaining a remote and impractical road, San Mateo County officials decided to abandon the road, but not without first paving it and installing gates to restrict public access. Today, only locals can access Bear Gulch Road, which is still as smooth as the day it was paved due to the sudden drop in usage.

One of the most important factors in determining a road’s public or private designation is whether the public can prove they were exercising their right of way. It’s a “use it or lose it” mentality. A 1970 court case decided one of the factors for designating a road public was if “the public had used the land for a period of more than five years with full knowledge of the owner, without asking or receiving permission to do so and without objection being made by anyone.” Furthermore, the public usage must have been by “various groups of persons” not a “limited and definable number of persons.”

Keep this in mind—it may be the key to keeping public roads public.

The Lawsuit

In September 1998, the case for Summit Road went to trial. Redwood Empire called multiple witnesses who claimed they had used the road dating back to the 1960s. Georgia Metzger said she traveled the road as a teenager in the 60s, and it was “common place for us as teenagers to enjoy.” John Nelson testified he had traveled the road numerous times in the 50s while pigeon hunting with his father, and nearly every weekend by motorcycle through the 60s and 70s.

Keith Cornick testified that he had participated in motorcycle races across Summit Road in the 50s, (I imagine every SRA member collectively rolling their eyes in the courtroom) but by the mid 70s there was too much traffic for the races to continue.

Redwood Empire sealed their argument by claiming that “once the roadway was dedicated to the public, then it could be used for any transportation purpose,” so long as that purpose wasn’t expressly illegal.

The court agreed, and on July 18th, 2000, Summit Road was officially and legally declared a public right of way.

The Aftermath

If you’re a cyclist hoping to traverse Summit Road like I was last November, however, you would be told a very different story.

While the gates on Summit Road are left open, they still exist and are covered with an intimidating array of no trespassing and no biking signs. So many signs, in fact, that it’s suspicious. One of them reads “NO TRHU TRAFFIC,” typo and all, followed by “right to pass by permission subject to control of owners.”

The road has been officially public for 20 years now and still the county allows these intimidation tactics to stand. To be fair, I received only friendly waves from residents when I rode my bike past the gate, but in the pit of my stomach I still felt like I was doing something wrong. What should have been a clear and simple ending to the story—Summit Road is a public road—turned out to be a lot more convoluted.

Responsibility

There is an important lesson to be learned for any public lands user in the story of Summit Road. Remember how Redwood Empire managed to convince the court that Summit Road was public? They relied on testimony from people who actually went out and used Summit Road. The most important thing you can do to help preserve public access to places you love is simply go out and enjoy them responsibly.

Some of these remote access roads need to be thought of less like roads and more like trails. If counties are increasingly likely to let go of their maintenance responsibility for stretches of remote roads in favor of private ownership, the onus is on everyone to help keep them safe and maintained.

Access to public roads shouldn’t be a “use it or lose it” dichotomy, but as infrastructure grows and maintenance budgets shrink, it seems inevitable that it’s the direction we’re heading in the United States. More and more roads are being swallowed up by frustrated landowners, big industry, and influential resident groups like the SRA.

Speaking of the SRA—I’m actually pretty sympathetic to their cause. No, putting up gates and locking the public off their road was not the solution. I’m not defending their actions, but I understand their frustration. The main group of road users the SRA was trying to keep off of Summit was motorcycle racers who were tearing up the gravel, causing unsafe conditions for residents, and leaving the road worse than they found it.

In other words, they were using the road irresponsibly. I can’t blame the residents for wanting to protect a resource they relied on. It wouldn’t be the first time a few bad eggs spoiled a good thing for everyone.

It is becoming less of a privilege and more of a responsibility for us as land users to exercise our right to these public rights of passage. If it weren’t for Metzger, Nelson, and Cormick using it as frequently as they did in the 50s, 60s and 70s, Summit Road might have remained locked behind gates forever.

In the age of technology, one of the simplest things we can do is document the places we go. If 50 years from now Summit Road is in dispute again, I’ll have photos and a Ride With GPS log showing that, in 2020, I rode my bike across with a friend—legally and responsibly.

Sources:

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/ca-court-of-appeal/1402765.html

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/ca-court-of-appeal/1713139.html

http://www.perfectsites.com/SRA/about.html

About Aaron Rickel

Aaron Rickel is a climber, cyclist, hiker, writer, and musician who grew up in the Santa Cruz Mountains and is now based in Los Angeles, CA. He has contributed to Outside, The Outbound, and The LAist, and writes about his outdoor adventures in the Los Angeles Field Guide and posts on Instagram @ajrickel.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.