How to Become a Sponsored Athlete in Bikepacking

How do folks make a living through sponsorship in ultra-endurance bikepacking? That’s a good (and complex) question. In this piece, Alexandera Houchin dives in head first with an honest and poignant look back at her ultra-cycling career and how she recommends athletes and brands evolve the conversation in the future…

PUBLISHED Mar 27, 2024

After eight years of (almost) continuously showing up for ultra-life and 11 years of long-distance bike touring, I finally, as a 33-year-old Indigenous woman, made “enough” money from sponsorships to dedicate my entire calendar to cycling.

| 2015-20 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bike Industry Sponsorships (Cash) | 0 | $2,000 | $5,000 | $10,500 | $21,500 |

| Indian Country (Cash) | 0 | 0 | 0 | $17,000 | 0 |

| Total | $0 | $2,000 | $5,000 | $27,500 | $21,500 |

A Long Story (Made As Short As I Could) of How My Sponsorship Journey Unfolded

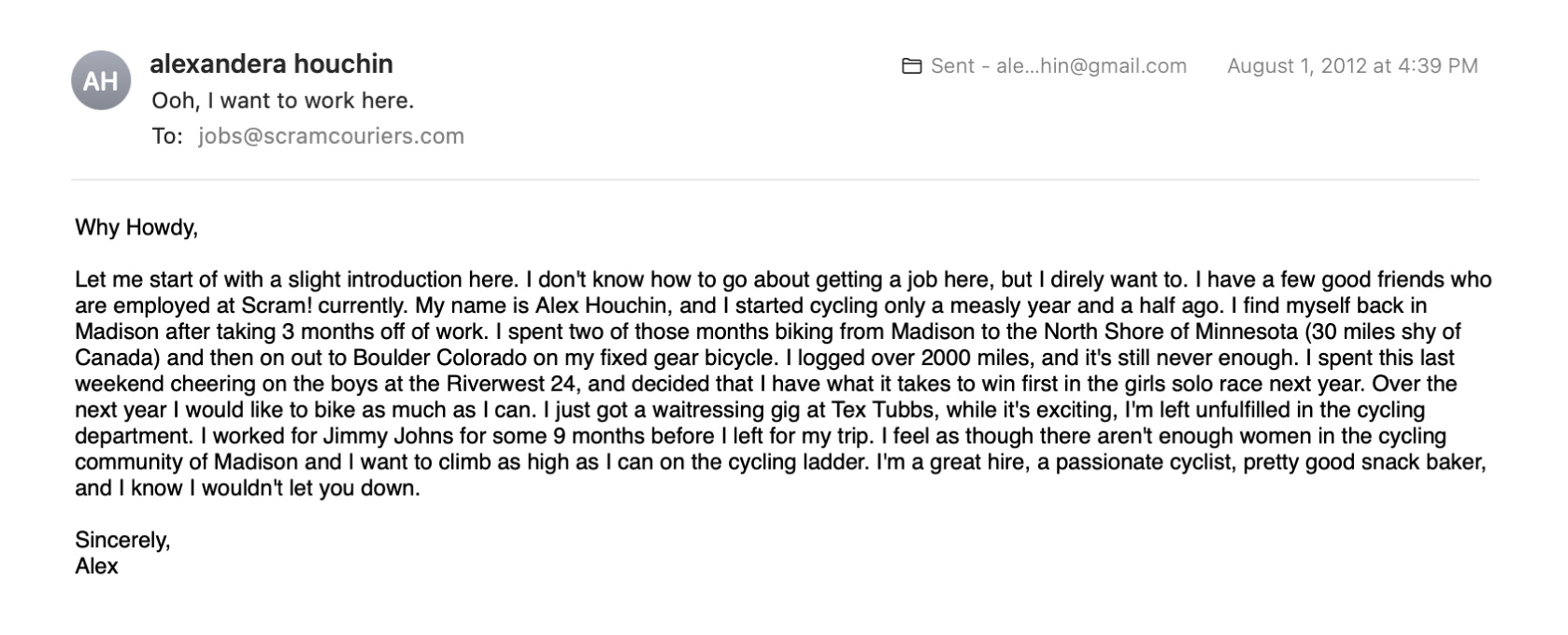

I learned everything I know about bike racing through trial and error. I had not seriously ridden a bike since I was a child when I started riding as a twenty-something adult. No one introduced me to bikes; bikes found me, and I fell in love with them. I didn’t know there were communities of cyclists. I had no clue that there was even bike racing outside of the Tour de France.

My first cross-country bike tour was in 2012. I set out for a 1,500-mile ride on my fixed gear State Bicycle with just a messenger bag, a tent, and a sleeping bag tied to a rack I’d attached. Why? This was the only type of bike I knew how to repair on my own, and shit, it was the only bike I could afford to ride in those days. I set out for that journey alone, with paper maps and a flip phone. I then continued developing my bike touring toolkit over two more years of solo bike travel around the Great Lakes region.

The first years of showing up for ultra-racing events included humbling trips full of non-competitive efforts. I entered the sport with insecurity and humility. I rode the Divide in 45 days in 2015, and by 2017, I’d set out for an Individual Time Trial of the Tour Divide, quitting just a few days in due to a weak mental game and an even weaker bank account.

This story is one I’ve been writing for a long time, going way back to the days when we would slam PBR in parking lots, practicing fixie tricks for hours into the night. My Madison, Wisconsin, fixie friends are to blame for how bikes took over my life; I was dying to feel truly connected to a community. We’d talk about our dreams of being sponsored or what it was like to Live and Ride in LA. I delivered for Jimmy Johns back then, getting fired when I refused to dye my hair back to a “natural” color from pink. I went on to work as a bike messenger with that pink hair and as a bike mechanic within the Roger Charly empire. For what it’s worth, Roger taught me many things that are still relevant in my life today. I was the first woman ever hired in that specific shop. That was 13 years ago.

I completed the 2017 Smoke-n-Fire race thanks to the Boise community; it was my first official ultra-race finish. By 2018, I was full-on in the ultra-racing game. I’d bought my Chumba Rastro and the rest of my gear with my own cash. In May of 2018, I ran a marathon and, five days later, found myself alone at Monument 103, the southern terminus of the Arizona Trail (AZT) at the Mexico border. I was pedaling north to Flagstaff. After over 600 miles on the AZT, forest fire closures put me in a position to make a decision; I changed my route. I’d hopped a bus to Boise and carried on north to Banff to start in the Grand Depart of the 2018 Tour Divide. I crossed the finish line as the first female finisher on a 27.5+ Chumba Rastro with three-inch tires that year. When I signed up, I had no clue I was even capable of “racing,” let alone “winning.” That win planted a seed in my heart that is now a fruit-bearing tree. I went on to earn second place woman in the Colorado Trail Race and fifth woman finisher in the Marji Gesick that year, all on the 27.5 steel hardtail I’d bought to aid in building confidence for mountain biking.

By 2019, I was back for the Tour Divide on a Chumba Stella, the first bike I received for “free.” I was officially sponsored by Chumba at that time, and they had big dreams, like me. I’d race the DKXL (now Unbound XL) on a singlespeed to practice for the Tour Divide. I’d line up for the Tour Divide again, praying I had what it took to win, even though I was on a singlespeed and wasn’t the favorite for the race win. Unbeknown to me, I would prevail as the women’s race winner for the second time in a row in the Tour Divide on a bike with one cog. I had started to receive sponsorships in the form of components, a bike, and bikepacking bags by then.

I was still working full-time while I studied for my undergraduate degree in American Indian studies and chemistry. By 2020, I’d finally graduated from college, and all of the big races were canceled. I had planned a Triple Crown Challenge effort that year. I squeezed in a Mid South ride on the fat bike and a Colorado Trail Race ITT effort in late June.

Come 2021, I was working two jobs: one with the University of Minnesota, Duluth, and another serving a fellowship within the planning division of my Tribal government. I wasn’t being paid by any outdoor or bike brands, and I didn’t receive my first cash sponsorship until the 2021 race season. I was dead-set on proving myself. I took the week off to race in the Colorado Trail Race in August, and by September, I knew I was going to try to do the thing. I quit both of my jobs in October to race in the Arizona Trail Race. After a fall on a rock wall in the Cochise Stronghold, I set out for the 800-mile Arizona Trail Race with two torn ligaments and a scrambled-egg ankle.

All I wanted for 2022 was to get a few sponsors on board so I could focus more on the work I feel we really need in ultra-racing and Tribal communities. I had no clue where to start, and I still kind of have no clue what I am doing today. I share the above narrative to illustrate the numerous tours, races and wins I accomplished to have credibility in the bike world before I was ever financially compensated. I share some insights in the following sections because my experience in becoming a sponsored athlete has been lonely, hard, mysterious, cutthroat, and vague. My hope is that I can validate my own feelings, share my truth and experience, extend some invitations, and set the incoming generation of ultra racers up for greater success in achieving their dreams (if they relate to being a sponsored athlete).

Where To Start?

Build Relationships, Not Transactions

In most cases, a business or a corporation holds the power pendulum in the athlete-sponsor relationship. Often, as an athlete, I have been in a position where my entire financial security lies in the hands of an athlete manager who comes from an entirely different socioeconomic, cultural, and racial background than I do. Meanwhile, the sponsor has thousands of prospective people waiting for the opportunity to work with them. Without taking time and effort to invest in our relationship foundation, we are destined to misunderstand the intentions or expectations that evolve through the duration of the relationship.

Relationships only last when they are built upon a foundation of respect. The differences between mainstream American society and traditional Anishinaabe society, in terms of relationality, differ greatly. I’m not here to say one is better than the other; I only want to illustrate how one set of cultural values has set me up to thrive while the other tore me apart. I am Anishinaabe, of the Algonquian peoples. A common practice within the community I belong to is to give gifts for just about any situation. From being invited into someone’s house, to asking a question, to building trust, gifts are shared. They aren’t obligatory calendar-specified gifts like the ones given on Christmas or Father’s Day; rather, they serve as tangible displays of being seen and valued at any time. A person’s presence, their time, their voice, their existence is a gift. This gift should be honored with an action; give ’em a fucking gift.

What I mean is that from both the brand and athlete perspective, I believe we should redefine the beginning (foundation) of a sponsorship. Instead of seeing it as either a marketing opportunity or a way to get free shit (and money), we should take a step back and take the opportunity to “be in relation” to each other. When I say be in relation, I mean to clearly communicate and understand the intention behind the relationship. Further, I use the phrase to be in relation as the verb translation of relationship, an act that is alive and needs nourishment.

As athletes, I think it’s important to remember why brands partner with people. Brands sponsor athletes because they believe aligning with a particular athlete will be advantageous to their capitalistic goals. Either their products will be exposed to a larger audience, or the athlete’s emotional connection to their following will influence purchasing power.

For brands, companies, businesses, and corporations, I’d like to suggest that athletes often seek sponsorship so that they can invest more of their time into training to compete in their sport. There are a lot of barriers to competing at high levels in any sport that vary due to the family a person is born into. Many athletes seek to become stronger, faster, and more skilled to push the envelope of their respective sport. They desire this for a multitude of reasons, not limited to winning, encouraging their communities to collectively break preconceived barriers by showing up as their strongest self, working toward self-actualization, being the face for the person they never saw when growing up, and notoriety. The reason athletes ask a particular brand to sponsor them is often because a brand’s marketing efforts imply that the racer’s value set is embodied by the brand they seek sponsorship from.

This is all to say that many of us lack the tools to communicate these deep, meaningful nuances and find ourselves trapped in transactional relationships that ultimately become disposable.

Find a Mentor (or Mentors)

Develop a relationship with a person who has experience in overcoming the barriers to entry you have experienced.

This doesn’t have to be limited to people who exist in the discipline you’re seeking to be sponsored in, but it should be someone who is doing similar work or has overcome similar barriers. Two of my biggest mentors have been my friend Sarah and my friend Reba. My friend Sarah does not have a career in ultra-endurance mountain bike racing, but she embodies the person I hope to continue to grow into. She’s an Anishinaabekwe from my Tribal community who operates a thriving business.

As a successful entrepreneur, community leader, and visionary, she has shared past mistakes with me and lessons she’s learned about navigating non-Native spaces as a Native woman; she has done nothing but lift me up, cheer me on, and aid in my successes. She’s guided me in navigating press requests and negotiating public speaking fees. She often serves as a reminder of my “why” when I get too exhausted from trying so hard. She is a call-it-like-it-is friend who isn’t afraid to speak her truth. I’ve learned just as much from her in observation as I have in conversation, coming to fully understand the value (and power) of invitation. She is my constant reminder that our Indigenous values serve us well.

I had a photo of Rebecca Rusch on the background of my computer when I was in my 20s. In 2021, Reba invited me on a bikepacking trip she organized as a small film project. I was a substitute for a last-minute cancellation and spent over a week asking her questions about her career as an athlete. After that trip, she shared tips with me on how I could begin asking sponsors for financial contributions on a professional level. She shared some industry connections with me, shared a little about her “why,” and offered insight on what it was like for her as a woman in sport.

She lowered some barriers for me as a woman coming into bike racing after she had set so many records and dispelled countless preconceived ideas about women in cycling. Plus, I saw parts of myself in her, and she was willing to share her story with me. She told of her journey to understanding her relationship with her father’s memory in the film, Blood Road; I saw my story of understanding my relationship with my mother in that film. I’ve met some heroes and had my heart broken by others, but in meeting Reba, I felt seen and respected. Plus, she’s still doing bikes. I hope to keep doing bikes for all the years to come.

Real Talk

Ask fellow athletes what they are being paid and share honestly.

This is a conversation I’ve been trying to have with my sponsored friends, competitors, and acquaintances ever since I started looking to make bike racing, writing, speaking, and competing my career. I have detected an underlying taboo radiating across the industry while attempting to have these conversations with other sponsored people. These awkward, complex conversations about such a personal thing (income) make these discussions feel extremely uncomfortable to me at times. Much of this comes because most athletes are juggling myriad things they do to make an income, and most of us have varying degrees of privilege to pair with our sponsorships.

There is an unrelenting air of competition for those of us seeking financial sponsorships from the bike and outdoor industries. The resource pot waxes and wanes with the booms and busts of the outdoor recreating economy. Therefore, at least in my experience, it’s easy to feel jealousy, envy, and inadequacy while having these conversations. I’ve had conversations with people who seemingly just entered the bikepacking or endurance racing communities and have received a great deal of financial support, while others have been showing up for years, displaying incredible feats of endurance, never having received any notable support at all.

I find it hard not to feel “less than” when I hear how much or see in which ways a particular person is being sponsored. Deep in the pits of my belly, I know (and believe) that one person’s successes do not dictate anything about my own worth. With this truth, I am genuinely happy for anyone who makes a living off sponsorships, despite the truth that I often feel resentment for their privilege. However, I believe there is enough “pie,” so to speak, for exceptional community leaders and skilled athletes to make a living from athletic sponsorships. I believe that collective conversations on contracts could lead to a more equitable funding future for all of us.

Advocate for Your Needs and Worth

Find your voice and use it.

Once you know what your competition is making, it becomes easier for you to ask for a “fair” salary. And yes, one must ask for it. The majority of my financial sponsorships are the result of me going directly to the partner I wish to work with and asking for a certain amount of money in exchange for (the following took me a long time to be able to communicate) the marketing benefits they receive from the visibility I add to their product line. There are some brands who met me where I asked them to, some brands who met me at a salary lower than I requested, and others who tried negotiating with me with what I perceived as offensive and exploitative offers. One must do a cost-benefit analysis when it comes to settling on a contract value.

Often, I have settled for less than I felt equitable because a) I believed in the brand’s mission and wanted to work toward collective growth, b) I felt backed into a corner and needed the money, or c) I believe that equitable financial benefit would present itself “down the road.” I’ve found that when I started having a firm, confident voice and expanding my vocabulary to include particular language in my dialogue, brands started to compensate me for what I asked, or at least what was within reason for their (usually small) business. Further, those who didn’t no longer occupy valuable time in my schedule and made room for the ones who do value my worth. I have found that if I hold strong to my bottom line, there are people willing to compensate me there or above. I then have to do less busy work and juggle fewer relationships with people who don’t see me in the place I see myself. Ultimately, you are your biggest advocate in these conversations.

Work With Partners You Believe In

Sometimes, it’s not all about the money.

This is a complicated one for me to digest. I have accepted less compensation in exchange for working with brands I believed in than I could have earned working with bigger, more resourced brands or corporations. As I learn more about how the sponsor-athlete relationship works in the marketing realm, I find this truth of mine to be bittersweet. I’m grateful for all that I have learned, but seeing a photo of myself in various places on the internet feels exploitative when I know brands are using it for marketing, especially when I hadn’t been equitably compensated for the use of my likeness in the first place. Why? As I navigate this world of marketing, I am learning to recognize the impact that the emotional connection between fans and the athletes they respect is invaluable. This connection sways consumers in influential ways.

As I find myself taking up space in the world of bikepacking marketing, I wish there was an infographic called “Marketing 101 for Prospective Sponsored Ultra-Endurance Bikepacking Racers” when I started. I do not think companies should profit from the platform, following, and life story of an athlete without compensating them with a negotiated salary, no matter the size of the business. There are creative ways a business can utilize tax law to build a sturdy budget for marketing. These are all the more reasons to work with a brand (or brands) you love and trust because love and trust are built upon a foundation of respect. Respect is a fundamental building block of equity. Equity recognizes power imbalances, and when those imbalances are addressed, all parties prosper.

I would like to note that I have a particular affinity for niche bicycle component artisans. Even though I could partner with a handlebar manufacturer or ride with other partners’ pedals, I desire to give more visibility to small brands and support their business dreams in a saturated bike world. In my relationships with those makers, I offer to purchase a product at full price as we develop a relationship and future marketing goals. I don’t think “free” is always better.

Nothing is free.

It’s Who You Know and How They Feel About You

Many people think quantity prevails, but quality is always what really matters.

I have been cultivating relationships across cycling for a long time. It started when I lived in Madison nearly 15 years ago. I did this through volunteering, working, sending written postcards to people, hosting people through Warmshowers, writing, and, most recently, building a social media presence. I resisted participating in social media until I finally received my first big ($17,000) check. I hoped that my absence from social media made a statement; I was not willing to market for brands who were not paying me. My relationship to Instagram is a business one, I use it as a tool for marketing. I wanted the world to know that after years of seeking financial compensation from the outdoor recreation industry, my first significant contract came from Indian Country—the very people I was seeking to invite into cycling.

After building a race resume that I am proud of, after writing about many important topics across the internet, after being a driver of Native narrative change, I could not convince anyone in the bike industry to invest significantly in my “marketing potential.” Even while setting out to finally complete the Triple Crown Challenge, a career-long goal I had trained extensively for, and the promise of a feature-length documentary of the race experience with Corey Rich, one of the world’s most recognized adventure sports visual storytellers, I could not acquire an investment of more than a collective $10,500 from my entire sponsor list.

Half of that financial input came from a single sponsor, Industry Nine. Clint had signed the very first sponsor check I’d ever received, and he’s invested in me in perhaps the most impactful way I’ve been lifted up through my career. Industry Nine financed Stronger Together, and the short film has provided me with more than an estimated $15,000 in speaking gig opportunities, and Brandon Watts (director) made concerted efforts to connect me with brands outside of cycling. Additionally, that film has brought new dialogue into cycling and outdoor spaces about the impact Federal Indian Policy still has on Native peoples today.

At the end of the day, ultra-racing has never been about the money. Most of my income comes from relationships I’ve built outside of the bike Industry. Corey and the Novus Select team paid me for my time while filming in 2023. I am compensated for my articles here on BIKEPACKING.com. A surprising amount of my salary comes in the form of small “grants” from individuals. People subscribe to my Substack, gift me through Venmo, or hand me an envelope of dollars; dollars that they earned and see no financial benefit from investing in me. I am an athlete supported by the people, for the people. It goes to show how important relationship building is between an athlete and their audience. Further, while seeking brands to partner with, my experiences have led me to believe that sending an email or note to anyone other than the owner of a business or the marketing department leads to being either forgotten or dismissed.

What Does This All Mean?

I am in no way complaining and truly value the journey I’ve had.

It took just one sponsor to change my life and perspective about the worth of my values. When the Eastern Band of Cherokee came to me and said, “What you are doing has made such a big impact in our community. How can we ensure that you can continue to show up?” I’d been trying to tell the brands I was having conversations with what I needed and who I was trying to represent and the pleas seemingly fell on deaf ears. I was attempting to go down the same pathways that other athletes traveled while pursuing sponsorships. However, the contract with EBCI was a poignant reminder that we should use our unique experiences and passions to find partners to work with.

Throughout my sponsorship journey, I promised myself that I would never “sell out.” To me, that means that there is no dollar amount that I would accept in exchange for disregarding my core values. I remind myself of this before I even entertain having a conversation with a prospective sponsor. My attempts at marketing are fueled by authenticity and are subtle responses to what I perceive as fallacies or comprehend as dissonance with current social media marketing trends. In general, I find much of what I see in marketing as boring, uncreative, performative, and disconnected. I want to live in a poetic world full of art in all her forms. I want to radiate in self-truth.

I am certain that there are sponsored athletes in bikepacking who make more than I do. I also know that I am truly blessed to be able to say that I signed contracts in bike land for more than $20,000 for the 2024 racing season. Further, that I can make ends meet when I couple that $21,500 with contracted writing and speaking gigs, even if it’s stressful, unstable, and unreliable.

Nonetheless, there is nothing in this world that lights me up more than racing my bike hundreds or thousands of miles; tears well up in my eyes as I type this. For all of those times where I pleaded with bosses, with lovers, “Why don’t you see my light?” I now know because my light dims when I ain’t out there racin’. It’s worth fighting for your light; it’s the only thing that guides us through the dark.

I end with a call to action for athletes who make more than I do. Invest in a mentee, or mentees. Invite your mentees. Connect them with your sponsors. This will ensure that there are more people out there who can humanize ultra-racing and bring their unique perspectives into marketing, especially people who are overcoming significant barriers to entry. I vow to continue doing this myself and to continue to cultivate relationships with the up-and-coming bikepacking ultra-racers, extending my knowledge and connections when I feel it is a good fit. Use your connections, privilege, and gifts to lift up another person (or people). There is no glory at the top if you live up there alone.

For brands, businesses, and the like, I urge you to take a chance and invite athletes into the marketing room to generate new ideas for how we sell this stuff. Further, we need to see diverse people in leadership roles across marketing. Hire them. This may require investing in someone who knows little to nothing about marketing when they start. But, with this investment, the return becomes exponential permitting diverse opportunities for a range of mentors going forward. I believe there is something special about the outdoor recreation realm; movement is medicine, and all of us are on a journey to be our best selves.

Let us use the gift of being our best selves to level up as a community.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.