More Than Just a Race: Le Tour de Frankie 2025 (Video + Story)

This spring, Mexican rider Paola Berber participated in Le Tour de Frankie, an 800-kilometer bikepacking race from Mexico City to the Pacific coast in Oaxaca. “More Than Just a Race” is a short documentary sharing her story of overcoming fear, illness, and other hurdles to complete the event. Watch it and find a detailed written recap of her experience here…

PUBLISHED Sep 15, 2025

In April, I raced Le Tour de Frankie, the first unsupported ultra-distance cycling race in Mexico. It covers 800 kilometers (497 miles) with an elevation gain of 13,873 meters (45,519 feet), starting from Mexico City’s iconic Zócalo and ending in Puerto Escondido, on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca. The route traverses the Sierra Mixteca, a rugged and ancient region that stretches across the states of Puebla and Oaxaca. Known for its steep terrain, deep canyons, and rich Indigenous heritage, it is home to the Mixtec people, one of the oldest and most resilient cultures in Mesoamerica, who call themselves Ñuu Savi, meaning “People of the Rain” in the Mixtec language.

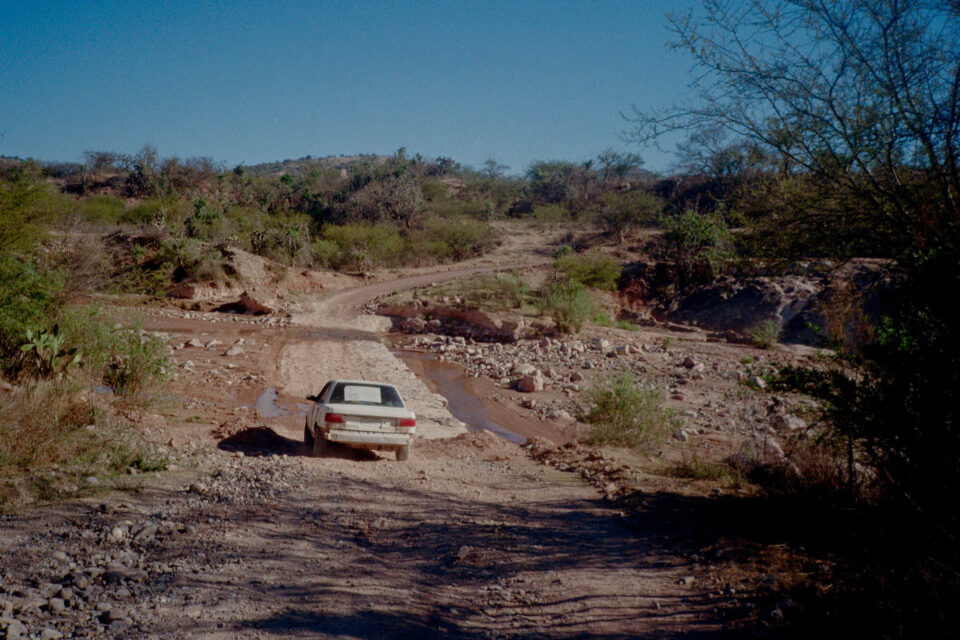

This was the fourth edition of the race, and each year, the route grows more complex. This version was by far the most technical yet, with rougher terrain and more remote sections. I’d say it was roughly 40 percent pavement, 50 percent dirt, and 10 percent Indigenous roads—new roads made by the communities they pass through, with a mix of hydraulic concrete and local rocks and materials.

For me, it’s so much more than just a race. As a Mexican woman, having the freedom to ride alone and feel safe is a rare privilege. Even though I know some places are safer than others, violence is a constant backdrop where I come from, which means safety is never fully guaranteed. You always need to stay alert. Organized crime shifts territories over time, and you have to stay aware of those changes.

But the risks go beyond that. Gender-based violence—harassment, assault, and even femicides—remains a persistent, often invisible crisis. Public spaces are not always safe or respectful toward women, creating in us a constant sense of vigilance. Even moments that should feel joyful, like going out on a bike ride, can carry an undercurrent of fear. Riding alone means facing a very real, everyday fear. It is always somewhat unsettling to be out there by yourself.

This year, out of 115 registered riders, only 12 were women, split between the solo and pairs categories. Just seven of us were in the solo female category. It makes sense, I rarely ride alone here, fear and danger are valid reasons not to. But for those same reasons, I saw this race as an opportunity.

To venture out alone still requires bravery. It’s not impossible, but there’s always an underlying unease. This race challenged me to unlearn much of what I’d internalized for my own safety: always ride with company, never ride at night. That all changed here, and I had to be okay with it. The race offers the chance to be looked out for by other riders, race officials, and dot watchers. Having that audience adds a small sense of safety, even though much of the riding is done alone.

I was nervous, but I tried my best to maintain trust in my own abilities and instill confidence in the organizers and their efforts. The way this race is organized feels like a collective effort to create a safe environment, and that, to me, is powerful. As a local woman, having the chance to ride with friends and acquaintances toward a shared destination feels like gold.

Into the Night

The race started at 1 a.m. on Saturday, April 26th. The city still felt busy, like any other Friday night. Around the Centro Histórico, people were out partying, music echoed through the streets, and the usual chaos of nightlife filled the air. Above us, the sky was clear, and the stars shone brightly, as if blessing our departure. In the Zócalo, it felt like a celebration of a different kind. Riders gathered with their families, sharing last-minute hugs, adjusting gear, and laughing nervously. You could feel the anticipation pulsing through the square.

We rolled out along Calzada de Tlalpan at a breakneck pace of 40 to 45 kilometers per hour (25 to 28 miles per hour). I was on a gravel bike with 700 x 45mm tires, and I’d never gone that fast before on my own with my bike loaded. It felt like a road race in the middle of the night. I tried to hang on to the peloton, but it was intense.

I clung on until we reached the first climb in Xochimilco, along the Mexico–Oaxtepec road. I settled into a more sustainable rhythm, still faster than usual. The first climb is a classic ride to La Loma, in the southern mountainous region of Mexico City. The temperature dropped significantly, cold enough to need a jacket, but the pace didn’t allow for slowing down. I didn’t want to be dropped, so I didn’t stop at all, not until the climb to Paso de Cortés.

Around 4 a.m., I reached the base of Paso de Cortés, a brutal climb with 1,600 meters (5,250 feet) of elevation gain over 23 kilometers (14 miles). On the climb, I started feeling a very unfamiliar cold, and then I saw snow; it was the first time I’d seen snow on the road. I slowed down. Riders started passing me, and I chatted with some of them. It was beautiful to see so many cyclists lit by headlamps under a starry sky. By 5 a.m., light began to appear, and around kilometer 92 (mile 57), I saw the peak of Popocatépetl volcano covered in snow. It was breathtaking.

I reached Checkpoint 1 at Paso de Cortés (kilometer 100/mile 62) around 6 a.m., much faster than my previous attempts. They told me I was in second place among solo women, and I couldn’t believe it. I felt great and didn’t want to stop for long. I took a moment to refuel and chatted briefly with familiar faces about the cold and the excitement of the route, took a photo of Popocatépetl, and continued onward. The descent is on dusty volcanic dirt, but the snow had packed down the surface. It was freezing. The temperature dropped below 0°C (32°F), and my gloves weren’t built for it. I endured, but my hands burned from the cold descent.

The descent from Paso de Cortés stretched over 40 kilometers (19 miles), dropping an impressive 2,000 meters (6,562 feet) in elevation before the weather began to ease near Atlixco, Puebla (kilometer 140/mile 87). Along the way, some cyclists asked if I was riding the famous ultrarace and kindly offered me electrolytes. I crossed paths with other racers, and sometimes we rode together for a while. Once the descent ended, I hit this horrible stretch of highway, an hour that felt like it would never end.

Entering the Inferno

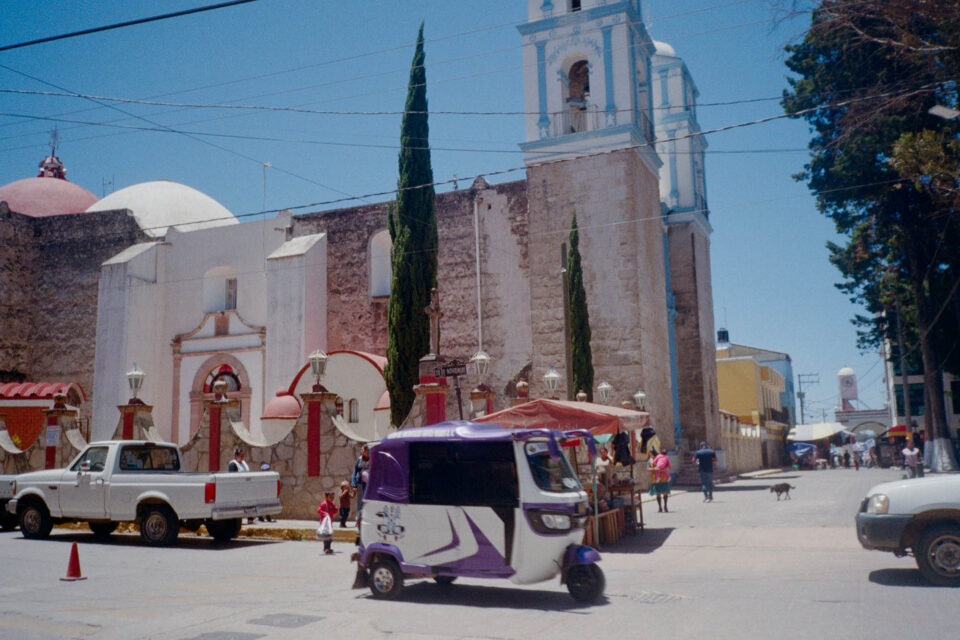

Around kilometer 170 (mile 106), we turned off toward the pueblo of Tepeojuma and entered a long dirt section. I reached Checkpoint 2 in San Juan Epatlán (kilometer 181/mile 112) before noon. I stopped for a quick meal, quesadillas shared with a small group of riders.

From here, things got serious. The 129 kilometers (80 miles) between Checkpoints 2 and 3 were brutal. My bike computer read 40°C (104°F), and it felt unbelievably hot. The terrain changed dramatically—semi-desert, full of towering cacti and thorny brush, with very little shade and brutally steep gradients, often around 15 percent.

At 2 p.m., under the harshest sun, I felt my body begin to shut down. I hadn’t slept since Thursday night, almost 38 hours awake. I started to move in slow motion. Near the Atoyac River (kilometer 234/mile 145), I found a small store where over ten riders had collapsed in the shade. Some were sleeping on the pavement, and my partner Cooper, who was also racing, was there too. I joined them and immediately fell asleep on the ground. Many people joked that this place was Checkpoint 2.5 because most of the riders stopped there for a while.

I awoke an hour later, still exhausted and now covered in ant bites. We waited until the sun dipped a little lower—around 4:30 p.m.—then I rolled out with a small group, determined to make it to Checkpoint 3. I had slipped into third place, with Zaira Contreras in second.

Night fell as we approached Santa Inés Acatempan. The climb into town was unrideable, and everyone was walking. Some riders lay on the roadside asleep, perhaps not knowing about the abundance of scorpions in this region. It felt surreal. I arrived at kilometer 283 (mile 176) with Simon from Germany and Ulises from Oaxaca. After searching around a bit, we found what barely qualified as a hotel and stayed the night. Around midnight, Tania Arana joined us.

At 5 a.m., Tania and I set off. We descended into the heart of the Sierra Mixteca Poblana as the sunrise painted the hills pink. We reached Checkpoint 3 in Acatlán de Osorio (kilometer 300/mile 186) by 7 a.m., greeted warmly by the checkpoint hosts with café de olla and pan dulce (sweet bread). Everyone agreed that the Santa Inés climb was brutal. After some chisme and rest, I continued alone toward CP4.

This next stretch was new. Last year, that section was all paved, but this time, the organizers added a rugged 70-kilometer (43-mile) dirt section, mixing gravel roads, trails, camino de campo, and even a section without a track, just rolling through native plants and rocks. Sometimes I ran into Tania, and we were swapping places for third. It didn’t feel like a race between us, and it was nice to have her companionship on that hectic section.

Navigation was tricky, but the people I met along the way were incredibly kind. Locals waved and wished me “Buen día”, and children helped guide me back to the route when I got confused. It was beautiful, and moments like those are part of why I love riding in Mexico. Mexican kindness is on another level.

That part of the Mixteca Poblana is so remote that you only really see old Nissan Tsurus pass by once in a while. I also rode with two locals from Puebla who brought great energy to that long, exceptionally hot, and dry segment. The climbs were steeper than expected. At noon, my bike computer read 45°C (113°F), but strangely, I didn’t feel it as intensely as I had the day before. Either I was getting used to the beating sun or my body was too sore in other ways to be distracted by the heat.

Eventually, I reached Huajuapan de León (kilometer 388/mile 241) at 4 p.m. I was officially in the state of Oaxaca. I shared a meal with other racers, took a two-hour nap, and then continued alone around 9 p.m., choosing to ride through the night to avoid the heat. After that meal and rest, I felt great on that road section; the air was fresh, the climbs were mellow, and I was feeling really strong.

Upon arriving in Tamazulápam, I stopped at the only open shop around midnight and bought juice, water, and bread. A local cyclist named Eduardo rolled up. He was a dotwatcher and invited me to rest at his bike workshop. At first, I hesitated because I don’t usually go with strangers I meet on the street, and I felt a little nervous. But we ended up chatting outside the shop while I chugged juice and munched on chips. Eventually, my friend Uziel showed up, looking totally wrecked, and we decided to go with Eduardo. He kindly let us charge our devices and even offered us coffee and rice. It was a small moment of warmth and kindness in the middle of the night that I didn’t expect but deeply appreciated. They were planning to host more riders that night and the next. It felt like a little oasis in the middle of the night, surrounded by bike parts.

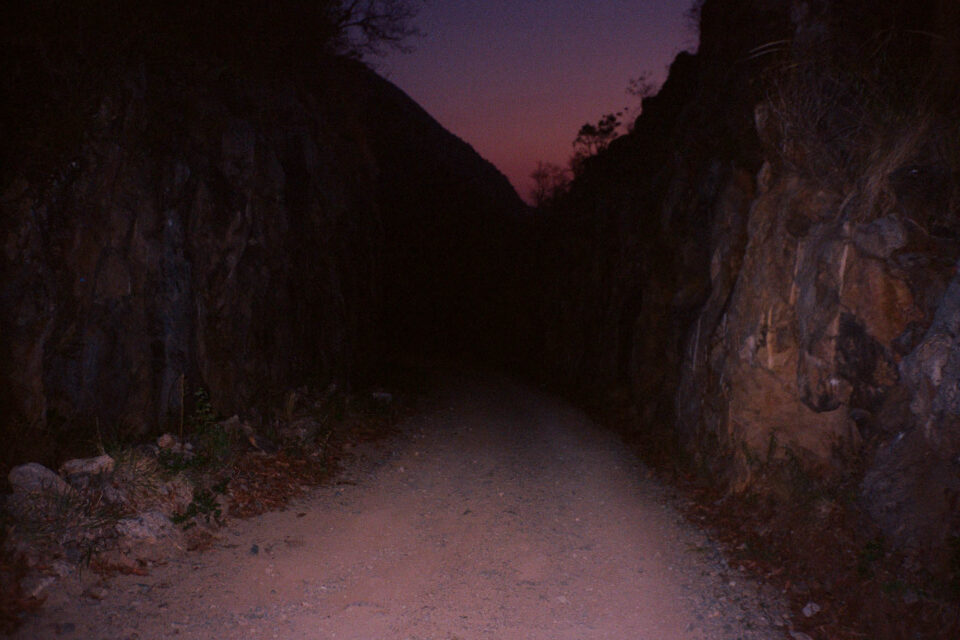

By 2 a.m., I decided it was time to move. I said my goodbyes and set out into the darkness. From Tamazulápam on, I was completely alone. Packs of dogs chased me barking ferociously and trying to bite my bike and heels—I stayed calm, splashed water at them when needed, and rode on, pushing harder to get away. Despite that, I felt emotionally strong. I played old cumbias on my speaker and kept pedaling.

At San José de Gracia (kilometer 460/mile 286), it got very cold. I saw the sunrise in the pine forest, one of the highest points of the route at 2,500 meters (8,200 feet) above sea level. The cool air was a relief. I ran into Simon again, who I hadn’t seen since Santa Inés Acatempan, before CP3. We rode together through the forest for a while.

Eventually, I lost sight of Simon and entered a stretch of carretera (paved road), where the heat steadily began to rise. There was no shade, just endless ups and downs. Despite the sweltering heat, I was feeling really strong; once again, I found myself in second place, ahead of last year’s female winner, Zaira Contreras. I felt motivated to keep pushing through, even with the heat. I didn’t care at that point. I just kept pedaling.

Breaking Point

I reached Checkpoint 4 in Chalcatongo de Hidalgo (kilometer 530/mile 329) in the heart of the Alta Mixteca (High Mixteca) around 2 p.m., still in second place. I needed to stop and sleep, but I pushed on to Santiago Yosondúa (kilometer 550/mile 342) to rest at a hotel I was familiar with from touring the zone. I devoured an empanada de mole amarillito and more pan dulce, and fell asleep.

By 6 p.m., I woke up feeling nauseous and vomiting. I brushed it off. I thought maybe it was the Sal de Uvas Picot, an antacid, I’d taken earlier, or maybe just nerves. I didn’t think it was a big deal. I got ready for what would be the hardest climb of the race, Vergel to Buenavista. I packed my things and rolled out of Yosondúa around 7:30 p.m., riding into the night.

Before reaching the race’s signature climb, I had to descend into El Vergel, a rocky, technical downhill that I tackled in complete darkness. I had to stop several times due to pain in my wrists. My stomach was still in knots, but I still managed to beat my time from last year. My technical skills have improved a lot since then. I feel much more comfortable riding a loaded bike on rough, rocky terrain.

The climb to Buenavista, the signature climb of the race, stretched for 21 kilometers (13 miles) with 1,600 meters (5,250 feet) of gain and brutal ramps reaching up to 15 percent. I started pedaling, but it wasn’t long before I had to walk. I was extremely thirsty and had gotten behind on my hydration. I tried to drink water to calm my thirst, but I immediately vomited. I tried again. Same result. That’s when I started to worry.

My stomach was in revolt. I had chills and a fever, and only a faint, intermittent cell signal. I messaged my loved ones to let them know I wasn’t feeling okay. It was past 11 p.m., and El Sereno (cold fog) began to roll in. Then, light rain started to fall. I felt like a shell of myself, barely present. I remembered I had my emergency bivy, so I pulled it from my deckpack, crawled under a tree, and went to sleep.

I woke up disoriented, unsure how long I’d been out. I tried to ride, but my body was very weak. I had run out of water, and after all the vomiting, the diarrhea hit, followed by sharp stomach cramps that left me doubled over. I felt miserable. I couldn’t possibly ride, so I walked. Then laid down. Then walked again, repeating this cycle for hours. Everything was blurry; at times, I forgot I was even in a race. Mentally, I was in one of the darkest places I’ve ever been.

Eventually, I reached a clearing and collapsed on the dirt road. Five shooting stars crossed the sky. I cried, overwhelmed by the situation. When I realized it was nearly dawn, panic set in. I had expected to complete the climb in six or seven hours, but it had been nearly twelve. I cried again because finishing suddenly felt completely out of reach; it had turned into a game of survival.

As the sun rose, another rider caught up to me. We didn’t talk much. He just said “buenos días” and kept moving. That tiny gesture helped me push through how I was feeling, so I kept walking the climb. I passed a wooden cabin with a hand-painted sign that read “Le Tour de Frankie” and “agua”, with a little bike drawn beside it. I called out, and a señora appeared. Her name was Doña Agustina, a middle-aged woman with long black hair and a gentle presence that immediately put me at ease.

She invited me into her kitchen. I told her about my stomach issues. She gave me peppermint tea and handmade tortillas, and to my luck, a loperamide. Then she offered me her bed. I hesitated, but I needed it. I needed such a kind gesture at this moment. I slept for about three hours.

When I woke up, I met her daughter, her grandson, and María Esperanza, their grandmother. They were all warm and kind. They told me they’d been watching racers for the last three editions of the race, admiring our efforts and putting out the water sign to help.

More riders came by, some stopped for water and to eat Doña Agustina’s handmade maiz azul (blue corn) tortillas. I chatted with the people who stopped, and some of them advised me to scratch. I said I’d think about it. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t want to risk my life; the next section of the race was one of the hottest, with no way out except descending 1,800 meters (5,900 feet). But I wanted to finish. Riding through that heat while already being severely dehydrated could mean a seriously dangerous situation. Making a choice was incredibly hard.

I couldn’t eat much; my stomach was still raw. Doña Agustina offered to have her daughter drive me to the next town, but I declined because it would mean disqualification. She mentioned there was an IMSS Clinic (a type of public healthcare center) in nearby Independencia, and luckily, it was just two towns past Buenavista, conveniently all downhill.

By 2 p.m., I started feeling a little stronger. I was able to eat and drink, so I decided to keep going, at least until the clinic to see a doctor. When I left, I cried, hugging the family goodbye. I felt so good spending time with them; their kindness and positive energy healed me. I promised I’d return. They were like angels on the route, and I was deeply grateful to them.

I reached Buenavista (kilometer 600/mile 373), the top of the climb, 14 hours behind schedule. I bought water at a tienda (small local shop), poured it into my bottles and hydration pack, then sat outside to drink. To my surprise, the water tasted like mezcal! I spit it out in disbelief. I went and told the shopkeepers about the strange taste. They apologized and explained that they often store the mezcal they make and sell in water bottles. After sharing a laugh, they gave me real water, and it helped clean my gear. Finally, after more time than I expected, I left Buenavista. The descent to Independencia was rough; my stomach cramped with every bump.

Finally, I got a phone signal. My phone lit up with messages from family, friends, and race organizers, all worried because my dot hadn’t moved for at least eight hours and I was out of touch, even from my tracker. I assured them I was okay and that I planned to continue at least to CP5, feeling a bit better, and headed to the IMSS clinic.

In hindsight, if I’m ever in a situation like this again, I need to stay in touch with the people who care about me. I have a satellite tracker with messaging features exactly for this reason, but I hadn’t sent any updates for too long. I didn’t make sure my messages were sending or that I was receiving theirs. I need to check in with my loved ones, especially when they know I’m struggling. I messed up.

I arrived at the Independencia IMSS Clinic just minutes before closing, around 4 p.m. The doctor confirmed I had a stomach infection and gave me antibiotics and medication to stop diarrhea and nausea. They told me I was okay enough to continue, which gave me a second wind. I wasn’t sure I’d finish, but I knew I had to try to make it to CP5 and see how I felt. Poco a poco.

I continued descending to CP5 with a stunning view of the Sierra Mixteca’s sunset. Around me, the sounds of chicharras (cicadas) signaled rain; it sounded like electricity buzzing through the air, and I could actually feel the vibration. It was a bizarre sensation.

Partway down, I ran into one of the race organizers, Jaime Napoles, sitting in the small pueblo called El Paraíso. He asked if I was okay, and I told him about my little survival adventure. He said everyone had been worried but was glad I was well enough to keep going. After saying goodbye, I continued toward CP5. It began to rain lightly, but the temperature was still warm, making the rain feel refreshingly cool.

The Last Push

I arrived at Checkpoint 5 (kilometer 612/mile 380) in La Humedad around 8 p.m. Some people there joked that I was still in the running for third place; Tania Arana wasn’t too far ahead, but at that point, all I cared about was finishing, getting enough rest, and staying hydrated. I ate a boiled egg with atole de arroz, kindly prepared by the people there. I rested for a few hours in a hammock. Around 1 a.m., I set off for the final major climb out of Santiago Ixtayutla. The road was paved with hydraulic concrete, but that didn’t make it any easier; the ramps were steep, often hitting 15 percent. At least my stomach had stabilized some, and though I had to stop occasionally to rest for a moment, I kept moving forward again, into the night.

The energy in that section felt spooky, though I couldn’t quite explain why. Last year, I sensed something strange in the forest as night fell, and out of curiosity, I asked some locals if they had ever felt it too. They confirmed that the forest carries a strong, unusual energy after dark, something not to be taken lightly. But this time, I couldn’t wait for daylight to make the climb; I was behind schedule, so I pressed on into the night. I kept my stops to a minimum, especially after spotting a few scorpions and snakes crossing the road that I did not want to go to sleep with. It turns out that snakes and scorpions are good motivators to keep moving.

At dawn, I reached San José de las Flores. I was close to the coast. I felt emotional. Locals greeted me with cheerful “Buenos días!” and kind remarks. One even joked that I could still catch up with the rest of the group that was far ahead, and it made me laugh. I wondered how many riders they had already seen pass.

At 10 a.m., I rolled into Jamiltepec, a bustling pueblo, the last bigger pueblo of the coast before reaching the state of Guerrero to the west. I thought about stopping for a bite, but I didn’t want to risk upsetting my stomach, so I kept going. There were only 100 kilometers (60 miles) left to Puerto Escondido, but they turned out to be some of the hardest I’ve ever ridden. By noon, the heat was relentless. I stopped at every tienda I passed, just to grab electrolytes, soak up a bit of shade, and do my best to stay ahead of dehydration.

The last 50 kilometers (30 miles) were brutal. My hands were in pain, my clothes felt unbearably heavy, and my skin itched like never before. I had never felt more uncomfortable in my life. At one point, I saw a pickup truck and, for a second, thought about hitching a ride. But no. I reminded myself why I came, how far I’d already made it despite everything. I was slow, but I was moving. I was determined to finish.

I reached the finish line in Puerto Escondido around 4 p.m. on April 30th. I was the fourth woman to arrive. My friends, my partner, and my family were there waiting. It felt like a dream. I didn’t reach the podium, but that was never the real goal. What I wanted was the opportunity to push myself harder. What I reached was something far more personal: a new edge of myself. I pushed beyond what I thought I could bear. I rode alone for hours and days. I faced pain, uncertainty, and even a visit to the hospital. And yet, I kept going. I finished within the time limit. I endured more to reach this year’s goal, but still, I rode stronger than the year before.

To Endure in an Endurance Race

This race made me reflect deeply on what “endurance” means. Endurance, for me, has become more than a physical measure. Basically, in an Endurance race, you have to endure challenging situations. But to endure is a deeply layered word for me, and it is hard to translate directly into Spanish, my native tongue, with all its emotional and philosophical weight. In English, to endure means more than just resistir, to resist, or aguantar, to hold on. It carries a sense of sustained presence through difficulty, to remain, to hold on, despite pain, fatigue, or struggle. It suggests another type of strength, not loud or forceful, but quiet and steady, coming from deep within yourself.

In the middle of an endurance race, you’re not just measuring fitness. You’re learning how to resolve, how to respond to the unexpected, how to stay calm when everything unravels. It’s not just about how many hours you’ve trained or how strong your legs are. It’s a mindset, one that only reveals itself when you’re far beyond comfort, when your body wants to stop but your mind chooses otherwise. It’s about lasting, surviving, and continuing, sometimes stubbornly, when circumstances seem overwhelming. This year, I didn’t win a medal. But I earned the unshakable knowledge that I can endure, that I can overcome fear and uncertainty.

I want to congratulate Zaira Contreras, Edna Gonzalez, Tania Arana, and all the women who participated in this year’s race. It takes courage to show up, to face the unknown, and to ride through fear, and we did just that. I feel deeply inspired by your strength and presence. Thanks to you, I’m more motivated than ever to keep preparing, keep pushing, and keep believing in what we’re capable of.

The Route

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.