An Afternoon with Slow Southern Steel

After meeting Jesse Turner at MADE in 2024, Nic caught up with the young framebuilder on a recent trip through Arkansas. Though their time together was limited, Nic got an inside look at the life of an up-and-coming builder amid the choppy seas that make up today’s bike industry. Pushing well beyond geometry and tubing choices, dive into Nic’s Field Trip to Slow Southern Steel here…

PUBLISHED Jun 16, 2025

I first met Jesse Turner at last year’s MADE show in Portland. We were both first-timers at the event, and I could tell from his timid stance that he was a little nervous. Squeezed into a tiny booth space next to Ashley King of Significant Other, Jesse brought something to the show that appeared like a bat out of hell. Evoking imagery of Black Sabbath and ripping trail metal, Jesse’s custom hardtail was something to behold. With my knowledge of mountain bikes lacking to this day, I knew next to nothing back then. All I saw was a bike that stood out amid a crowd of perfectly manicured show bikes.

Part of it was down to the paint job. The sparkle beneath the void black base paint was a great contrast. Another standout element was the custom, ideally balanced Buckhorn frame bag with a flame pattern stitched on the side. But a lot of it was subtle and wouldn’t become clear to me until I spoke to him almost eight months later. Having kept up with Jesse and his framebuilding operation, Slow Southern Steel, via Instagram, I was excited to catch up and potentially ride with him as I ventured toward DOOM in early April. Hailing from near Fayetteville, Arkansas, Jesse was a local and someone intimately involved with the increasingly notorious event. Having roomed with event organizer Andrew Onerma, he was involved in the early days of the Ozark Gravel Cyclists (OGC), the organization that laid the groundwork for DOOM.

Eventually, Jesse would become consumed with happenings in his own life and allowed Andrew to take OGC in a direction all his own. The two remain close, however, and Jesse has continued to fabricate custom bikes for Andrew’s various ventures as he flirts with the pointy end of ultra-endurance events and bikepack racing. Jesse, having some experience welding as an art school student at a sculpture program at the University of Arkansas, became more engrossed in the reality of making bikes. After attaining his art degree, Jesse decided to buff up his welding experience and attended a program at a local technical college, Northwest Technical Institute near Springdale. Working for various architectural welding shops and a trail company, he’d entered the program with the distinct purpose of learning how to build frames. Growing up in the area, Jesse always enjoyed bikes, but he’d thrown himself into the arts and the act of making. While he knew he wasn’t ever going to make a career of welding bespoke pieces of art for one-off clients, the welding courses he’d taken at the technical college, combined with his time in art school, eventually coincided into the distinctive style I saw at MADE in 2024.

First for himself and then others, Jesse’s desire to build bikes is one pushed forward by his friends. As we took an afternoon away from the purgatory-like basecamp of DOOM 2025 to visit his shop near Fayetteville, it became clear how much of a community endeavor Slow Southern Steel is. For context, I’d gone to DOOM only to scratch about 25 miles in. As I’ve said more times than I care to admit, I fell into a river and lost my shoe in the first singletrack section of the race. Luckily, after soft pedaling my bare foot back up to the aid station nearby, I hopped in a car that was headed back to the start in Horsehoe Canyon. In the car was Jeremiah Harenza, a general contractor fresh off the 50-mile option Andrew introduced for those who couldn’t do their initial route choice because of the delayed start.

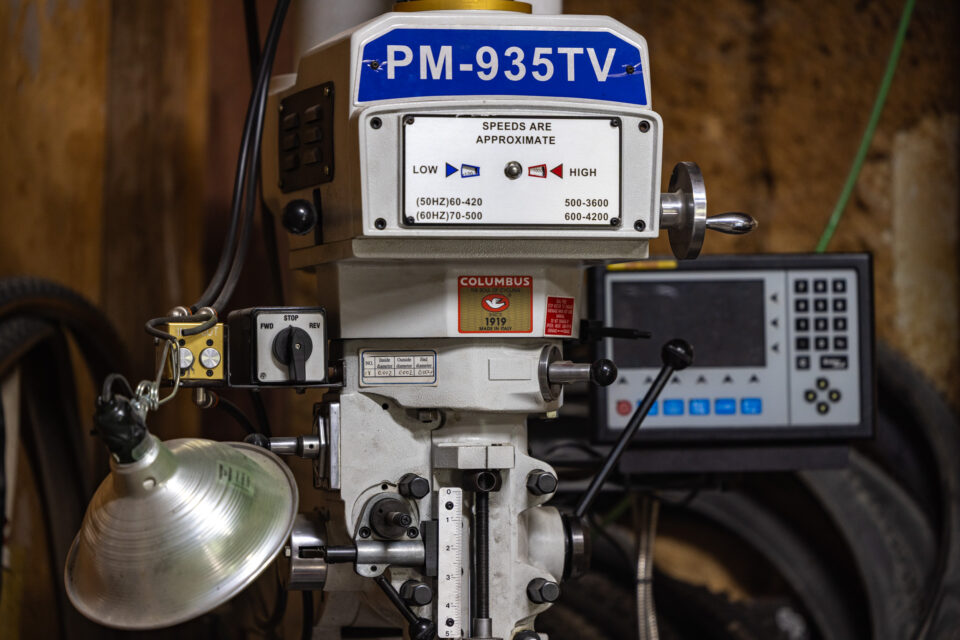

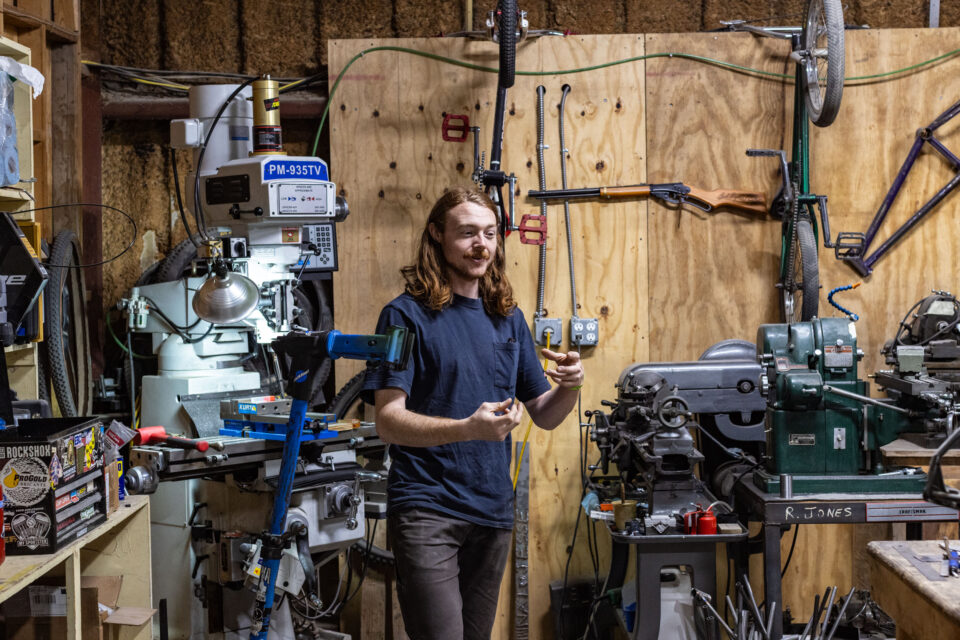

Jeremiah is a good friend of Jesse’s and the primary leaseholder of the building he “rents” out to Slow Southern Steel. I scare-quote the term because it is, in effect, a rental agreement of a bike per year in exchange for Jesse’s use of the space. In reality, it’s just the back of the building Jeremiah’s small company uses to fabricate, gather, and hang out in—but it’s a huge boon for a small frame builder with thin margins. Walking into the dingy, sawdust-covered back room, Jesse prodded me toward the left side of the space. “Don’t look over there!” he laughed. “It’s a mess!” In what was really only half the area he was allotted, Jesse’s ideas, tools, and workspace lay bare. A series of small tables, a dog bed, some old frames he’d taken inspiration from, and mementos from his past, Slow Southern Steel is little more than an ambitious young man and a dream of building frames for a living.

As we chatted through a busy work day for Jeremiah’s crew, Jesse showed me a Specialized Sequoia. “The paint was really cool and something that inspired the look of some of the other stuff I’ve made. But, man, this felt way ahead of its time. It was one of my favorite bikes, and one that showed me what else I needed to ride out here,” Jesse said. Among the other objects was a crumpled MASH track bike he sought to save for a friend, some extra trophies he’d made for the winners of certain categories at DOOM, and cast-offs from his BMX-oriented youth. Speaking to the lack of frames in the queue, Jesse spoke to the realities of being a young builder. With bills to pay, part of the benefit of working out of his friend’s contracting business is that he’s able to join in on the custom installation jobs that seem to be at no end in the exponentially developing northwest corner of Arkansas. Hopping in on the occasional job isn’t Jesse’s favorite task, but it’s something the keeps him sharp and can allow him to see things differently when not exclusively working on bike-oriented projects.

Jeremiah soon walked back in the room and joined in on the conversation. Having scratched from the 50-mile option, he looked happier than the sopping mess he was the day before, evidenced by him ribbing Jesse about his lack of orders. Open to allowing his friend something of an incubator toward success, Jeremiah isn’t the only person pushing Jesse forward. Notably, his partner, Natalie Peet—an accomplished bikepacking racer and a real up-and-comer in the women’s ultra endurance cycling world—has raced Jesse’s bikes to some big wins. Despite going down pretty hard in the final miles of the brutal course, she took the crown at this year’s DOOM and won Colorado North-South the year prior.

As we drove back toward Horseshoe Canyon Ranch to catch more of the finishers, Jesse opened up further. “That’s the thing about framebuilding. You don’t want to charge someone too much when you’re new to it because you don’t feel like you deserve it. So, you hook your friends up at cost or less because you just want to make something. Jeremiah’s a buddy, and when he was married, other builders told me—that’s what you have to look out for. A frame breaks, and your buddy might not sue you, but their partner could,” he laughed nervously. “But luckily, nothing has ever broken. Andrew, Nat, myself, and all my other friends have really put these things through the paces and never found much to be wrong. So, I guess that’s good, right?!”

While waiting for Natalie to finish her race, we spoke about everything from opinions on UDH designs to growing up in Arkansas. Jesse told tall tales of those who still willingly live out in the “sticks” and how the people of the state made things work. It’s a culture and context that seemed to influence not only his approach but also his style.

Always wanting to push the envelope, though, I asked Jesse a question I think is pertinent to any builder: why someone should buy their frames. In a golden age of production bikes, spending significantly more on a custom offering from a one- or two-person operation doesn’t seem feasible for many people. What Jesse said in return was fitting and consistent with where he’s at in his journey:

“Arkansas is a pretty crazy place. I think the aesthetic of my bikes is subtle but unique, and it kinda bleeds into what works around here. You rode some of that stuff out there. The kinds of routes and rides Andrew is putting together. It’s pretty brutal and taxing on a bike. I like to have a thicker, sturdier tubeset toward the bottom and thinner, daintier tubing toward the top. It gives it a classic, solid aesthetic that is sort of moto-esque in my mind, but also gives the people who ride around here stiffness, durability, and flex where it works.”

He’s the kind of builder who could go on forever if you didn’t stop him. Endlessly interested in the nature of framebuilding, Jesse’s formal education in the arts clearly carries over to his style. When asked about the intentional elements of his designs, he said, “The bubbly, drilled aesthetic on the drive-side chainstay plate is part of it. I do that by hand, which gives each bike something distinct and unique. And the seat stays too. They’re thin, and I think a lot of people tend toward “S” bends these days. I prefer mine straight and to the point. It also allows me to get creative with other elements at the back. Like on Nat’s bike, for example.”

I’d seen what he was referring to a few days before on Instagram—a chainmail-like seat stay bridge for his partner’s last-minute race rig. “It’s not a structurally important area, so adding that bit of flair for Nat was fun and something I really liked doing. I’m still in the process of creating my own aesthetic, but I feel it’s something at least some can recognize. I have people asking me for frames sometimes, and, respectfully, I don’t really understand certain requests. People ask for custom builds that are nowhere within the styling of what I’ve built before. Like, why are you asking me to build that? I want people who buy a bike from me to want something that is distinctly mine.”

Looking at Jesse’s first real go at a full build, you can see what he means. Though the details of what makes a great product have improved through practice and a skilled hand, his style has been discernible from the get-go. A true artist at work, Jesse is as interested in making a living off bikes as he is in creating something he’s proud of. I couldn’t help but feel a bit more invested in his journey after spending time together. Having entered the business end of the industry at a similar time, I see some parallels in our paths. Sometimes, when going to a trade show or storied shop, I feel like I’m delving into a world of context I can only partially grasp. Stories of past golden days fly above my head as I try to understand, but with Jesse, I feel like a cohort. Inspired by a shared generational context, Jesse and Slow Southern Steel is a framebuilder born of my age. With an impressive early showing, I know I’ll be keenly tuned in to whatever he churns out next.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.