At the Speed of a Camel: A Self-Supported Stone King Rally

Set in the French and Italian Alps, the Stone King Rally is a six-day enduro stage race in which riders receive shuttle assistance to the top of timed descents. Intrigued by the event but wanting to do it her own way, Lee Craigie rode the route self-supported, bikepacking between stages and resupplying in small towns along the way. Find her story with additional photos from Camille McMillan here…

PUBLISHED Sep 19, 2023

Words by Lee Craigie, photos by Lee Craigie, Camille McMillan, and Alice Lemkes

There’s an old Arabic saying that the soul can only travel as fast as a camel. If there’s even a grain of truth in that, then, in our modern world, we travel almost everywhere without our souls. Everything is so immediate. Time is money, and money is everything. Our attention spans are shrinking, and we are suffering. It’s a choice I’ve made not to fly to the start of a bike adventure. My reasons began as environmental, but, lately, they’ve become more personal. I’ve realised how much richness seeps out of an experience when I try to cram too much in. I’ve begun to question what the point is in traveling somewhere without my soul.

I have always wanted to ride the Stone King Rally, a six-day enduro stage race through the French and Italian Alps that ends on the Mediterranean coast. The route begins in Arvieux and follows some of the best singletrack in the Alps. Participants in the Stone King get shuttled to the top of several timed sections each day and race each other to the bottom. A typical day includes an accumulated height gain of between three and four thousand metres and ends with the finest hospitality from a carefully selected variety of alpine communities.

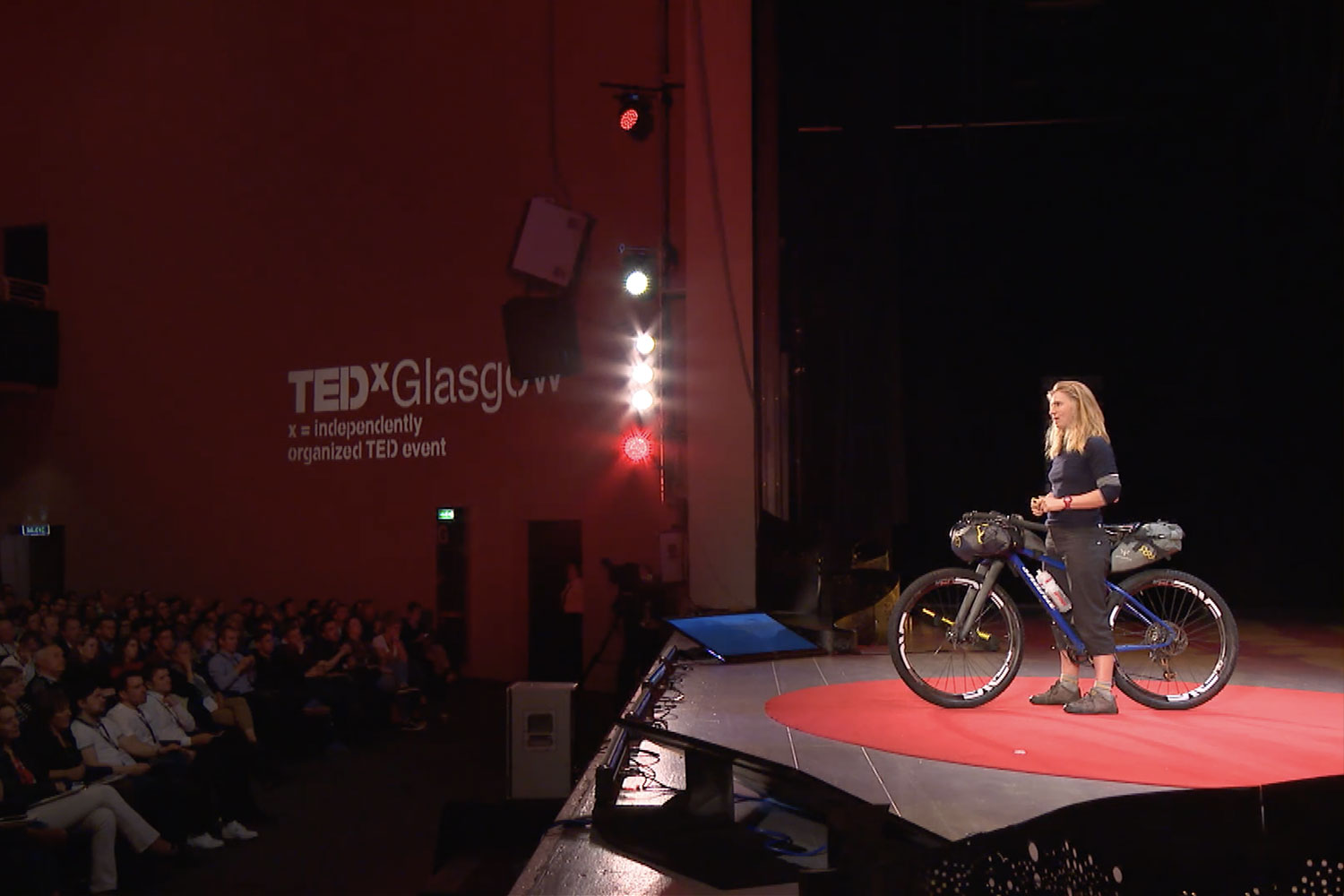

The Stone King Rally is a hard, technical route that eventually delivers riders to the sea exhausted and reeling but utterly euphoric. I could see the appeal of racing this route, but I know that flying to a start line and being shuttled to the top of descents would leave me feeling unfulfilled. Instead, I wanted to ride the route under my own steam and travel to and from it using trains and ferries. I would carry everything I needed to eat and sleep along the way, resupplying from local shops and camping on high cols. My ride would be different but—I hoped—simpler and more peaceful this way.

I spoke to Ash Smith, the Stone King Rally race organiser, unsure what he would make of my plan but was pleasantly surprised by his enthusiasm. Ash works tirelessly with local communities to uncover new trails through his beloved mountains each year, always with the intention of bolstering the local economy and giving something back through his trail stewardship. He loves the mountains and mountain biking and wants mountain bike tourism to be a sustainable source of income for remote communities.

Not being a self-supported riding enthusiast himself, Ash was unsure what it would be like to bikepack his route, but he was up for helping my attempt in any way he could and gave me invaluable information on what I could expect from each stage, including some “wormholes” I could use to miss out some of the race route should time not be on my side. I already knew that time would not be on my side and that it would be my mission to ensure I didn’t let any feelings of time running away impact my ability to remain fully present and enjoy each moment as if it were a gift I’d never have the chance to unwrap again.

I let the race get underway before I began my journey. When the gun went off on the first stage of the 2023 Stone King Rally, I was floating somewhere on the North Sea between Newcastle and Amsterdam. From Amsterdam, I’d break my bike down into a bag and carry it on a high-speed train to Paris. At the Gare du Nord, I’d reassemble my steed and ride through Paris to the Gare de Austerliz, where I’d board the night train and slumber away the miles between Paris and Briançon before riding over the Col d’Izord to reach the beginning of stage one.

On paper, the whole thing looked like a painful and expensive faff, but in reality, once I had accepted the inevitable pace of things, I knew I’d appreciate the privilege of arriving in the Alps with my body and soul intact. The mountain clothing equipment company Rab would pick up my travel costs, keen to support a low-carbon adventure and promote their new biking range. I’d travel to the Alps with my partner Alice so we could document the journey properly, but almost immediately, she would return home to complete a long overdue Ph.D., leaving me to journey south alone. I’d document the majority of the journey using a camera phone and a drone until meeting up with photographer Camille McMillan somewhere in the Maritime Alps.

It takes time for me to let go of the feeling of always having to be somewhere else. As an ex-mountain bike racer, my natural instinct is to move quickly and efficiently as soon as I begin turning the pedals. With one eye on the incredible media being pumped out of the Stone King Rally Instagram account, I found myself all fired up to ride the route fast, but I was to quickly discover that a fully loaded Julianna Joplin couldn’t be coaxed into drifting around corners or pulling endo turns on steep switchbacks (not intentionally, anyway!). I would have to try and tuck away my ego and let go of my ambitious daily mileage to embrace a slower, more contemplative journey.

It was unseasonably warm in the Alps when I set off. Having traveled from my home in the Highlands of Scotland (admittedly, slightly faster than even a very fit and fast camel), where average July temperatures are around 16°C (61°F), meant I slammed into the dry heat of the southern Alps like it was a brick wall. After 3,000 metres (9,850 feet) of climbing and a similar amount of technical singletrack descending on the first day, I was utterly cooked. I had traveled only half the vehicle-supported day-one race distance, but I crawled into my tent at 8 p.m. after a wash in glacial water and a noodle soup dinner.

I lay under the flimsy canvas and watched the sun sink behind the ragged horizon, preparing myself for the contrasting cold of the high camp, which, when it came, hit me almost as hard as the heat had. But when day two dawned, it brought with it that familiar euphoria of having survived the first night of a multi-day journey. It doesn’t seem to matter how often I do this stuff; the first night of a journey when traveling solo is always full of trepidation. Thankfully, the following morning is usually equally emotive and life-affirming.

I settled into a steady rhythm of sleeping high below barren alpine outcrops, then waking and bracing myself against the crisp morning air to wait for the sleepy sun to dry the fabric of my single-skinned tent. I’d brew a coffee, then pack up and begin my descent to the valley floor below, first through green meadows littered with more wildflowers than I could appreciate in a lifetime, then scrubby steep slopes of valiant willow and struggling knee-high birch and finally on loose, steep singletrack through fully established pine groves.

The air grew thicker and warmer with every metre in height I dropped while I focussed all my attention on the rocks and roots I had to navigate to reach the valley floor. Once there, I’d breathe again and set about finding a cafe or shop to resupply from before beginning the next long climb in the steadily building heat. Often, I’d have to sit out the heat of the early afternoon in the shade of a tree or the shelter of a bar and ride into the cool of the evening, all the while dropping further behind the race route itinerary. I had to remind myself that this didn’t matter and that I was free to adapt my route and leave out sections the race had covered if I wanted to. My journey differed from that of the fast-moving enduro racers edging towards the Mediterranean coastline a few days ahead of me.

After five days of this peaceful, simple way of life, I traversed around the high balcony above the town of Tende, and the route simply stopped. I paced back and forth below an impenetrable barricade of vegetation before finally realising I had to ride through the hillside by way of a dank, dark corridor built by the Italian military in the 1930s. I entered the pitch-black tunnel and fumbled towards a shaft of sunlight I thought I could just make out at the far side of the bunker, but it turned out to be a fist-sized hole in the crumbling wall. I turned around and shuffled tentatively through the maze of dark corridors until I eventually found a bike-sized opening on the other side of the hill. I emerged into the warm daylight and dropped down to Tende on a fast and fun mountain bike trail to begin the next, very different, installment of my journey.

Camille McMillan is a photographer and mountain enthusiast based in the French Pyrenees. By his own admission, he is not a hardcore mountain biker, preferring to interpret the world in shapes and colours using his camera and creative imagination. I met Camille in a bar, and together, we drank 10 beers while discussing our objectives for the remainder of the journey.

I had employed his services to help me capture the images I needed to tell this story, but as it turned out, Camille would do so much more than that. His languid riding style and sense of the aesthetic meant we would share a journey of rich, linked experiences rather than one driven by the single distant objective of reaching the sea. His presence helped me temper the ambitious pace that, despite my best intentions, I’d been struggling to let go of. We began stopping more to explore the faded grandeur of abandoned train station buildings now bursting with foliage through their deglazed windows and marvel at the speed of the clouds as they poured upwards over the tree-covered mountainside.

With the hot, dry weather now behind us, we were forced to adapt our high ridgeline traverse route and instead drop down to a remote mountain refugio to sit out a storm. In the two days we spent storm-bound in the Refugio de Allavena, we made friends with Hugo, a wandering poet from Bordeaux, and Laura, a herbalist and one of the hut guardians who detailed in passionate Italian the richness of the flora and fauna all around us. We stayed up late drinking grappa with these incidental friends and put the world to rights while the stove flickered and hissed and the rain bounced off the tin roof.

What might have been a frustrating time became an experience rich beyond my imagination, and I found, to my surprise, that I felt real disappointment when the rain finally eased, leaving behind it a fog thick enough to obscure any view but easy enough to navigate south through. We reluctantly left the refugio to make our way down to sea level through young oak growth and loamy singletrack, pausing to drink expensive wine and then sleep our final night in an abandoned apartment building in Perinaldo.

The beach at Bodighera was hot and teaming with holidaymakers running in and out of the swell that sucked audibly at the pebbles our bikes lay abandoned on. I joined them in the tepid water and let the rip tide tug at my tired body, and then we drank a final beer in a beachside cafe before boarding a train to Nice. I sat on the packed train, staring at where the immense blue of the sea met the vastness of the sky, and I struggled to remember any details of the cold, high, rocky cols that had been the backbone of my journey up until that point.

Two days previously, while we had been writing poetry huddled around a fire in the mountains, 90 mountain bikers had stood on this beach and showered each other with celebratory champagne before hopping onto flights home carrying bike bags and memories of their journeys. I wondered if, by now, they had had the chance to reflect upon their incredible journeys or if they’d returned home and had to keep up the frantic race pace of everyday life. Normal life lay just a train journey away for me, too, but I found myself feeling real gratitude for the delayed speed at which I would reach it.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.