The Blind Bikepacker

Aly Winkler, now four years past her diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa, an eye degeneration disease, is still out there chasing her dreams of seeing the world before the lights go out. Evan Christenson caught up with her for two weeks of pedaling together through the rolling hills and glaciated peaks of Patagonia. Read on to discover Aly’s truly inspiring story…

PUBLISHED Apr 9, 2025

An impossible proposition, the blind bikepacker. Pedaling alone among the most rugged terrain in the world with two lonely and narrow black straws of vision. Two pieces of penne pasta to see through, to survey rocks and ruts, dogs and mountains, maps and men, the vast world careening around and squeezed to the sole blip directly in front. Head swiveling, five meters at a time, 40 miles an hour, days from civilization, months into the journey, months still to go. A solo woman, a broken inReach, the cultural barriers, the delaminating tires. This proposition, to ride across Latin America alone legally blind, it’s absolutely terrifying. But Aly Winkler, four years on from her diagnosis, two years since we first met, she’s still doing it. Pedaling, camping, painting, living. The blind bikepacker she is.

Aly was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa in 2021. She dropped everything, leaving her seasonal work as a tree planter to go and hike the Continental Divide Trail. A seasoned traveler, having already backpacked Europe, horse-packed in Iceland, and thru-hiked across New Zealand, she was keen on finding more independence. She was told her vision would eventually disappear completely. And with the tunnels closing in, she left to go see the world. She went hiking. Then she bought a bike and headed south.

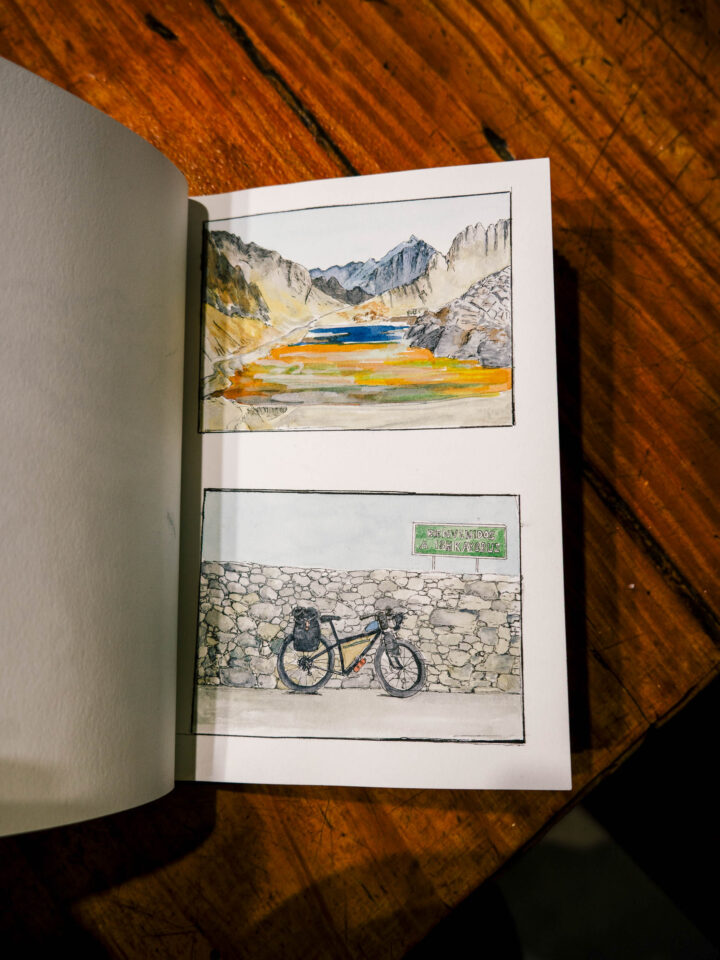

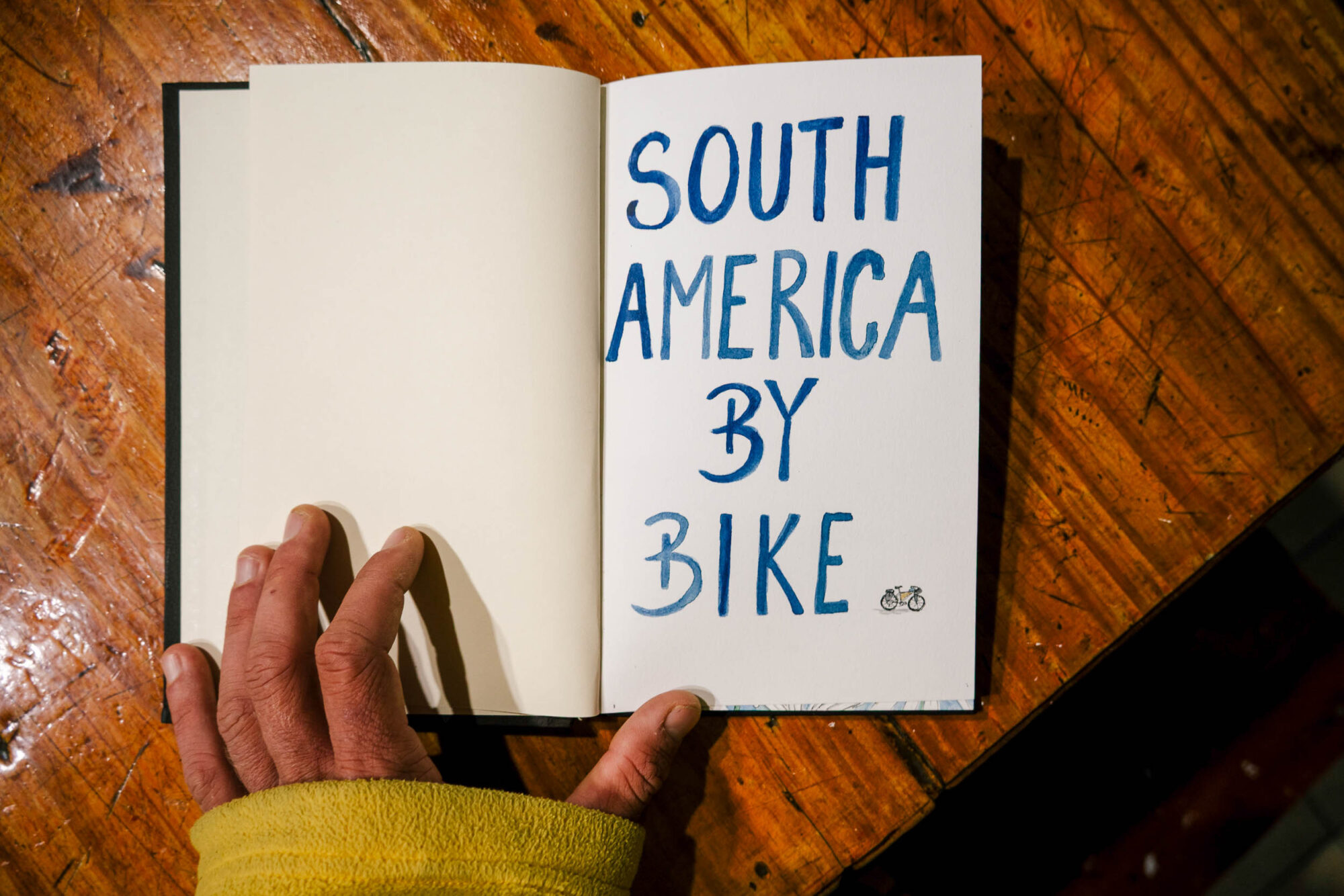

Aly and I first met in Mexico, when she was riding the Baja Divide as part of a longer push all the way to South America. But she returned home afterward, hunkered down to really learn Spanish, worked a bit, and reset for what would become this trip, nine months of riding from Peru to the tip of the end of the world. She admits she skipped ahead to what will undoubtedly be most of the highlights of any ride across the Americas. The High Andes, Bolivia, the Atacama, Patagonia. Aly didn’t know how much she would be able to do before the vision went dark. And with a worry like this, shamelessly, you eat your dessert first.

Unplanned, we met back up in Chile, where the famous Carretera Austral gets into its full swing. Here, this far south, the lands narrow, the peaks shoot into the sky, and this world of fire and ice tightens and gets more raw. Hundreds of thousands of tourists a year come down here to Patagonia to see these iconic peaks and set foot on a glacier before they all melt. Tourism infrastructure surrounds, with hotels and tour guides and buses everywhere.

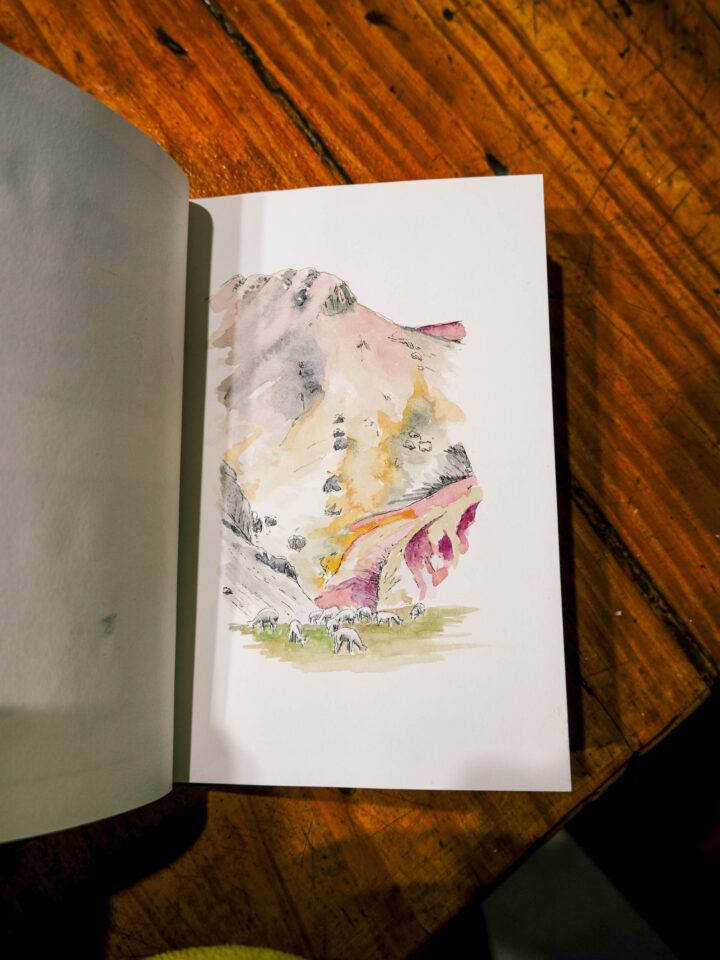

Growing tired of the cars pounding the washboard and billowing their dust clouds, the English hostels and the park fees, we set off into the mountains on small dirt roads and rickety wooden bridges to get out of the rut and away from the zoo. The spirit of bikepacking is best found in quiet corners of big mountains. And in the heart of all humanity, these empty horizons are where we are forced to feel the most alive. Aly prefers these places, the places with more condors than people, where camping is as simple as stopping, where no one prods at our tents in the night or heckles us to buy wristbands. These places still exist here in Patagonia. But only if you’re willing to load up and push a bit.

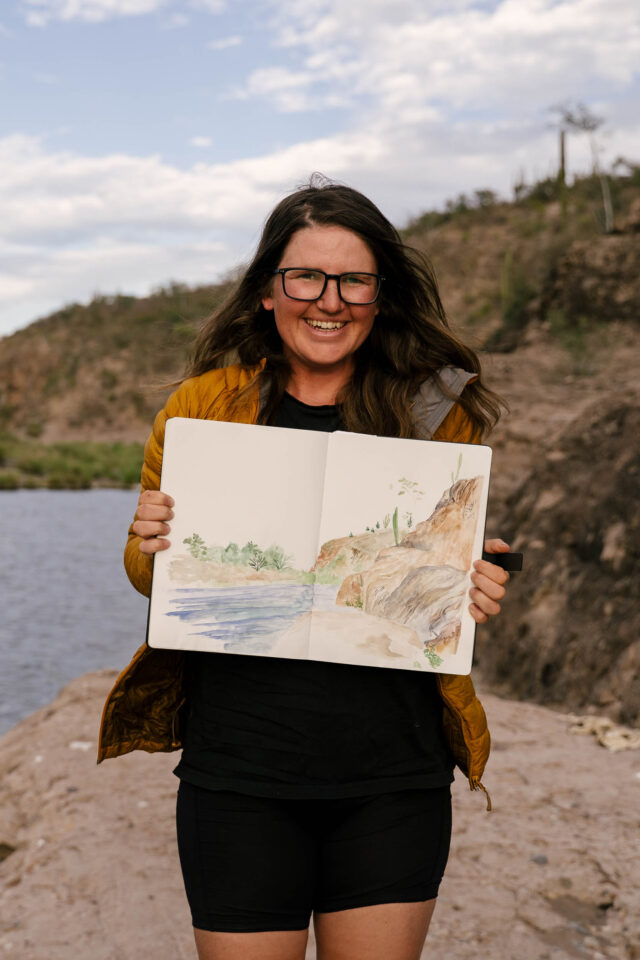

Aly led the charge. With all the blogs and maps in her head, she captained our ship, and we followed the blind bikepacker into the hills, through cow-trails and river crossings, and we saw a side of Patagonia typically reserved for cowboys and their herds. We camped in riverbeds, we camped with strangers, we hitch-hiked for resupply and got lost bushwacking in swamps. Aly, every hill, every turn, attacked it all, rocking her loaded bike underneath, flicking through GPX files, fixing flats, moving forward. She is unstoppable. Aly is always a small dot in a massive landscape, inching along the horizon, her camera in her hip pack, her watercolors tucked away and waiting. Legally blind, riding the biggest and most intense landscapes on a bicycle. She laughs a lot, a ferocious giggle, aware of the audacity of pedaling a humble bicycle into the headwinds that pummel the pampa. Singing, dancing, looking around at the small tunnels of information in front, deducing the things lost around the edges. She’s just having fun. Isn’t that why we all ride?

In riding together, it’s her tirelessness I admire. She is the first one up and the hardest on the pedals. She’s on the heaviest bike and sprinting until she collapses into her tent. She attacks the hills and dares her derailleur to keep up. She speaks the best Spanish of our group, and grabs the conversation when we ask for directions, the subtle French bien her small Canadian accent mark. She reads all the blogs, picks through all the files, keeps up with all the group chat messages, and makes the most informed decisions. There isn’t the valor of fearlessness here. It’s a realistic amount of skepticism and knowledge. Aly is experienced and educated, with hundreds of nights camping in the backcountry relying on just herself. She calculates her risk. But she knows this time is incredibly valuable, her vision now down to about 20 percent of what is normal and slowly decreasing.

Aly, like most cyclists and outdoor lovers, builds her love of the world on all things visual. To all of us bikepackers, vision has to be the most important sensation. We follow our eyes along the trail and they weep when visually it is so overwhelming in its beauty. Aly’s artwork focuses on reproducing these curious things she’s seen along the road. She swings her old Nikon DSLR and takes dozens of photos a day. And later, she stays awake in her tent to watercolor and sketch them, picking apart the details she likes the most, omitting those less pleasant, and one page at a time, layers together these stories, of her and her bike alone in this world so foreign and fantastic. With all of this, she is savoring this flavor while it still lasts.

Riding with her, it’s easy to forget the blindness. She’s confident in her movement and independent in everything. It only shows up in little moments. She struggles to track birds in the sky. She leaves high fives hanging constantly. Tire levers on the ground are impossible to locate. Nighttime is impossible, and her headlamp is her most prized possession. One day, loading our bikes into a rattling old lumber truck to hitch through the mountains, to punch through the headwind, and to make it to food before we ran out, the three of us tossed around in the back, wood chips flying all around, the thin cliffside road promising death if we rolled over the edge. It was cold, and I was nauseous from the smoking, rumbling truck and the tightening curves. As the truck gurgled higher and higher, and my head began to spin, I looked to my right, and there was Aly, sitting with her rain jacket tucked around the edges, casually doing Duolingo on her phone.

We sat down for a chat down in Puerto Natales, a few weeks before she would finish this massive trip and head home to start back up in school. She’s leaving tree planting now, after having planted several million trees in total. She’ll study map-making and programming and try and find a job she can do once she goes fully blind. Hopefully, there’s more big trips like this one before that day. She leaves a trail of joy in her wake, chatting and giggling with ranchers and riders on the roadside, shocking them when, days later, she reveals her secret. Ultimately, the world is a better place with people like Aly riding around it. I was so grateful to ride with her. Oh, how we had an adventure.

So much has happened after nine months on the road. How do you look back on this ride?

It’s been fucking awesome! Yeah, it’s been such a good trip. There really haven’t been a lot of low moments. I think it’s really exceeded my expectations, not that I started the trip with a ton of expectations, but just so much beautiful riding, incredible vistas, and the people have been so kind. Stuff has gone wrong, but not in a terrible way. You know, enough that it makes it interesting, and adds some stories. What a trip. There have been some really good people.

When we first met, you were riding a gravel bike on the Baja Divide. Tell us about your new bike. How’s it different or better?

Oh, yeah. Wayyy nicer. I walk a lot less. And it’s more reliable. I feel like I’ve grown up a lot in the bike world, and that’s been really cool. But before Baja, and even now, I still feel like you can do any route on any bike. I saw the other day that some guys rode to the Everest Base Camp on city bikes in the ‘60s. We get so caught up in this idea that you need the perfect bike for the trip. That really bothered me in Baja, because there would be all these men who would tell me I couldn’t ride my bike there, even though I was already doing it! And when men tell me what I can or can’t do, I just want to do it more!

If I rode my gravel bike here, it would have been fine. I would have slashed some more tires, maybe. I would have walked a bit more on the sandy bits. But whatever. I love this bike. My shoulders hurt less. It looks cool. It’s a good bike.

Is there something specific you hope to get out of these big rides and adventures? Do you have any particular goals in mind? Or is it more like, “Let’s just go have fun?”

Definitely more “let’s go have fun.” These trips are where I’m happy, where I feel most like myself, where I feel the most alive. This is where I want to be. I want to be on the move, seeing new places, experiencing new things. I don’t think it really serves my purpose to come down here with set expectations. Vague goals, maybe, but I want to come with an open mind and see what happens.

Have your goals or intentions changed with your diagnosis?

Definitely. I used to travel a lot more on my own, trying not to see anyone. But there’s something special about sharing these moments with people. It’s been lovely sharing this trip with so many people, because those memories don’t have to live fully alone in my head. And I’m well aware that down the road, I’m probably not going to be doing these trips. So, with the diagnosis, it’s really like, “How do I want to spend my time?”

That question was something I dwelled on when I was first diagnosed. I had this feeling that I had to see as much as I could every day. I got more intent on documenting everything, especially those first two years. I thought, “Well, fuck, if I go blind soon, I want to go back and look at these things.”

Blindness, as you know, is a spectrum. I’ll probably still have a pinhole of vision down the road for a while. But my vision has been pretty stable. When they first diagnosed me, they had no idea if in five or 10 or 20 years I would be completely blind. But that worrying is softening a bit. Still, before the diagnosis, I loved to travel. I had pages and pages of places I wanted to go to. And that’s still there.

Does the purpose feel different now?

I think in the first few years, yeah. But now that it’s been a couple of years and I’ve seen a lot and have done some incredible things, I feel so grateful and privileged. And now I feel like if this is it, then that’s okay. I’m making the choice to go home and go back to school. I could keep biking. But at some point, we all have to grow up.

To me, the point of all this silly bike stuff, of traveling, of this shitty hostel, is to squeeze out the juices of life. Are you worried that with blindness comes an inability to do that?

To me, yes, it feels that way. I don’t think that statement would apply to everyone. But my life has become centered around the outdoors and being outside and working with my hands. This is what I love to do, and being fully blind is going to close a lot of those doors.

And to top that off, my other passion is doing art. So, that’s going to close too. I love being alone, the tranquility and the solitude. Someday I’ll need someone to escort me, and that’s just not the same.

You know, when I was diagnosed, I had never heard of blind people going out and doing things. It’s a part of my own biases, figuring out how to navigate the world. I had never thought about disabilities before this. Why would you? But I’ve met some people since who see only pinholes, and they still go mountain biking! And they do it so casually. I’m so impressed by those people.

How do you feel being a solo woman traveler? And does the blindness add a level of intimidation to that?

I guess I’m proud in a way, going against stereotypes, and showing that it’s possible. I think representation matters. I really like when I meet young girls on these trips, especially if they’re from cultures where women don’t do sports or have the same opportunities. And I love talking to the young kids and saying, “Do you ride a bike? Do you want to? You can too!”

But being a solo female traveler, I hate the question of, “Where’s your boyfriend?” Or “Are you safe?” And I know women get these questions a lot more than men. It’s great that men and women and non-binary people do these trips, but I just wish there wasn’t that divide. It’s totally doable to travel like this. The blindness layers onto it, for sure. I take a few more precautions. But I think that applies to all women. We all have to take more precautions. We have to be more hidden at night. Stay more in hostels.

And there have been some weird encounters on this trip. Especially in Peru. But then I’d say I have a boyfriend, and they would treat me differently. And to me, that’s not okay. That makes me out to be property. That’s lame.

To wrap it up, what do you have to say to someone who wants to tackle a big ride like this but feels something holding them back?

Just go do it! People come up with a lot of reasons they can’t do something, but I think it’s mostly mental. Start with an overnighter. It’s not that complicated. Just pedal. If you can’t pedal, then walk your bike. It’s very meditative.

You can keep up with Aly on Instagram.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.