Wild Times on the Trans-Uganda

Share This

This past summer Evan Christenson took a blind leap and cycled the Trans-Uganda alone. Along the way he found much more than he expected and the experience was beyond life-changing. Read on for his passionate reflection on the trip and see a collection of photos from the route…

Words and photos by Evan Christenson

Uganda is a land of incredible extremes. Vast, empty desert extends from smoking, overpopulated, and underfunded cities. Lush jungle layers atop towering mountains and in between it all is less of a gradient and more a set of reaching, decisive hurdles, all seemingly impossible in magnitude. Uganda’s already other-worldliness traverses massive ecological variance on a small, high-velocity scale. It’s like pedaling across a new continent every week, and with each barrier comes an emphatically unique signature to the ones lying before it. I’m hiking a volcano’s muddy slopes in the east. I’m alone for days in the hot, empty northern desert. I’m riding through rivers and crossing the Nile. I’m slashing through jungle and thumbing rides through game parks. I’m climbing through tea orchards at 8,000 feet and taking ferries to islands in Lake Victoria. I’m battling chaos in the old capital. I’m back on a plane and leaving it all behind. So soon? Oh it burns. Even still.

The Trans-Uganda is demanding. The Trans-Uganda is incredible.

The Trans-Uganda brings a particular set of challenges unlike any I’d experienced prior. There are people everywhere in Uganda. I’d read it before I left, but I couldn’t really understand its implication. Even in Los Angeles, a city of 12 million, I can ride all day and only talk to five people. But in Uganda, being Mzungu, you are hounded. You are whistled at. Kids chase you. They grab on to your saddle pack. Motorcycles honk and those hanging off trucks wave. Every market brings beady eyes and excited questions. “Where are you from, Mzungu?” and these questions follow you everywhere. Five weeks I spent there alone, falling all the while deeper and deeper into isolation. I highly recommend doing this route. In fact, I almost insist. But bring a partner. The attention is far too much to shoulder alone. It broke me, and in devastating loneliness I would try and rebuild myself at night only to be broken again in the morning. I would shower in cold water and tears and return to my tent alone to listen to the call of the mountains, so close and so magnificent and let them help me forget the soft draggings of footsteps nearby.

*Don’t yell at the kids. Their laughter turns to stone throwing and cheers turn to hisses.

One of the implications of people being everywhere is the pace it dictates. People in Uganda are so joyous and loving they excite with their kindness. The Africa time moniker they love so much means you’re pulled into conversation and held tight until the light begins to dwindle and the roads fall asleep. Ugandans are proud of their country and its resilience to the surrounding commotion. They’re proud of its fruitfulness and relative opportunity for the past 30 years and in turn boast commanding smiles and fill the air with guttural laughter when welcoming foreigners. They approach with genuine curiosity, and those that live in the dirt are eager to invite you in and offer shelter during another much too frequent rainstorm. Their presence is both unsettling and reassuring. Food is everywhere, help is never far away, and buses are always close to take you back to Kampala if needed.

Early on, I took a bus back to Kampala to replace a busted shifter. The two days in transit became probably the most stressful time of my entire life. Long, hot stretches of loud music, crying babies, and newfangled claustrophobia were highlighted by the chickens and goats meandering around the people shoving cheap electronics in our faces. The old buses racket over potholes and I could almost feel my bike breaking underneath my spine.

People sell cassava, candy, and books aboard the buses too. Mostly self-help, but everyone was selling Animal Farm by George Orwell. Just $0.75 for a little irony- Museveni has now been in power for 33 years.

Back on the road after a very helpful stop at Ultimate Cycling (helpful and knowledgeable. The only bike shop with 11-speed in the entire country), I extended the route another couple hundred miles north to Kidepo National Park. I met two experienced cyclists who made it clear how different that part of the country is and why I had to make it there. In the north, Karamoja tribesmen herd cattle and sheep across empty, high desert plains. The roads finally quiet down and it was here I could finally begin to process the first two weeks of the trip. Karamoja is so different from the rest of Uganda. The lions, elephants, and elands prowling the park in Kidepo make for incredible vistas. However, you cannot ride a bike in the park, but for ~$30 you can hire a truck to drive you through. I suggest you camp in the park while you have the chance. Jackals and warthogs walk aimlessly around the tents and under mountain sunsets. Bonfires and cheap beer make for a blissful celebration of making it all the way north. It’s all equatorial from here.

The roads leading into Kidepo are impossible if it rains. And I mean impossible. Clay packs onto into and over itself and adds 10kgs. The wheels quit turning and mud clings to your shoes as you slip, carry, and push for hours in an earthly fit of hell. I was there late August and the rain was punishing. Keep an eye on the weather and have plenty of clearance. I brought my Rodeo Labs Flaanimal, a standard issue gravel bike with clearance for 650B x 50mm tires. I used every millimeter of clearance, but bring more if you can. Other than that, I loved the gravel bike. You don’t need a big mountain bike, and the northern extension includes some long, smooth dirt roads and highways that are perfect for the gravel rig. The Chinese have been building roads in exchange for permission to extract oil from the National Parks, and there’s a beautiful, empty highway in the North. No one uses it. Yayyyy China.

The next major portion of the trip leads into the mountains on the western border with Congo. The Rwenzori mountains are epic. Mt. Stanley (named after controversial explorer Sir Henry Stanley), is home to the only glacier in Uganda. Even at its base you can expect snow in the rainy season. My 40 degree sleeping bag was absolutely punishing for the couple nights I spent camping, but nevertheless I found myself pleasantly content to sit, shiver, and stare at the mountain peaks dancing with the clouds.

Climbing into the Rwenzori mountains involves a couple days of impossibly steep and loose dirt climbs where even at full power I could only push an average of 12kmph. This means the bored kids living in the remote mountains have all the time in the world to run with you and play. Some of them are fun and joyful, but a lot of this includes begging. Don’t give in if you find yourself there. The begging will follow you everywhere, and the children grow reliant and quit attending school in search of more handouts.

Queen Elizabeth National Park is a disappointment. Pedal through and spend more time in Kidepo, Murchison Falls, Lake Mburo, Elgon and Bwindi.

The route then follows the border with Congo to Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. It’s here the mzungu come to play. Safari trucks buzz about. Chapati (unleavened bread) prices inflate from $0.10 to $2.00. Boys and girls skip school and sell art to passing tourists, and you can pay $600 to go on a hike with rangers through the forest to where the wild silverback gorillas live. Did I do it? It wasn’t the plan, but “You’re really going to come all the way from America to Uganda and not see the gorillas?” made me reach for the camera and pull out the wallet.

Do I recommend it? Absolutely. The excitement of hacking through jungle and eagerly looking for a gorilla was worth it alone. The thrill after a paw came over the top of a nearby tree was icing on the Ugandan cake. Later watching a newborn climb all over its mother? Unbelievable.

Tourism in Uganda is still a small scale operation. They see roughly a million tourists each year, which in retrospect is a surprising amount. Outside of the National Parks I would see a handful of mzungu in small cities and villages working for NGOs, and little elsewhere. The resounding question I was asked after returning makes that one million figure even more surprising: “Was it safe? Were you in danger?”

Uganda has a bad reputation in the West solely due to it being lumped into the same black box with the other East African countries. It’s wrongly associated with the Rwandan Genocide, Ethiopian Famine, and the civil wars in Congo and Sudan. Uganda sits alone in the middle of all of this turmoil, and against all odds celebrates a peaceful and prosperous recent past. There has been one kidnapping and one small terrorist attack in the past 15 years in Uganda, making it far safer than travel to Western Europe, or even me sitting in class back home in Los Angeles. I never felt threatened by anyone there, other than the few cases of having rocks thrown at me. Would I go alone again? Probably not, due to the intensity of the isolation. But absolutely not because of the danger. As with all travel, just don’t be an idiot.

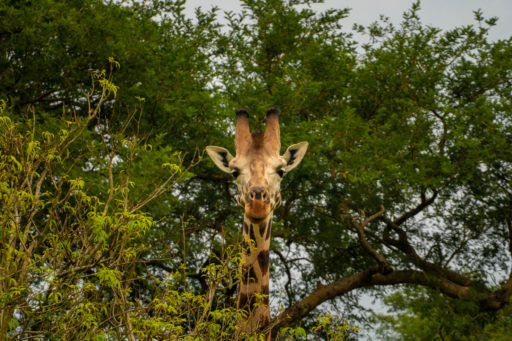

Back on the bike, you carry on east back towards Entebbe. Here, you get the chance to ride into Lake Mburo National Park. You can rent a mountain bike from some of the local lodges, (I personally loved The Eagles Nest, camping available) for a ranger to ride while they protect you through the park. Here, thousand strong packs of zebras and impala run across the plains, and baby warthogs scurry about the fields. If you’re lucky, you can even drop the bikes and walk with the giraffes as they snack on tall African acacia trees and gracefully stumble around. It’s an emphatically humbling experience. The last one of the trip.

Then you ferry to Kalangala Island, the biggest island in Lake Victoria, where most of the forests have been cut down and replaced by palm oil plantations. The ferry ride is itself a chaotic adventure, and the one I found myself hungover on my final morning was easily 100 over max occupancy. We packed together like mukene (sardines) pulled out from the murky waters below and amidst the noise I met the two most interesting men I’ve ever met.

And then you finish. And then I cried. I fell to my knees and shook as the tears flowed from my eyes overlooking the dozens of scars and calluses that had collected from gripping too tightly to life and falling off whenever I guessed wrong. In a tidal wave of no longer avoidable memories I sat at the shores of Lake Victoria and let the emotions somersault like a 70-pound bike down the slopes of Mt. Elgon. Before Uganda, I had never spent more than six days alone, and my experience in the developing world was so narrow and naive. Electing to spend my summer chasing enlightenment through small villages, desert plains and jungle was less of a step and more of a blind and chaotic leap.

The Trans-Uganda is not a vacation. Hell, it isn’t even an adventure. And when it’s not an excursion either it lapses between a pilgrimage and an exercise in life. You’ll find everything new and some things terrifying in Uganda. Your lens will be shattered and rebuilt with dirt, and everything will look different both during and forever after. You’ll question the world and your place in it. You’ll question humanity and the scope of it, and the route will question you and all of your ability. Along the Trans-Uganda you’ll find controversy, poverty, and suffering. You may find food poisoning, a hospital, and police interrogation like I did. Throughout it all you might even find yourself whatever that means. But along the Trans-Uganda you will find love, not-so-hidden in its most dense city centers and most desolate desert reaches. I guarantee that you will find that love. And finding love on a bicycle is the best way to go about that exercise on life. I guarantee that, too.

The Trans-Uganda is a 1,312-mile bikepacking route purposefully created to take in the incredible parks and landscapes within Uganda. The route promises to deliver an unforgettable experience via a mix of singletrack trails, jeep tracks, and the most rugged dirt roads on the continent… all the while connecting the sights, people, and places that makes Uganda ‘The Pearl of Africa’. Learn more here.

The Trans-Uganda is a 1,312-mile bikepacking route purposefully created to take in the incredible parks and landscapes within Uganda. The route promises to deliver an unforgettable experience via a mix of singletrack trails, jeep tracks, and the most rugged dirt roads on the continent… all the while connecting the sights, people, and places that makes Uganda ‘The Pearl of Africa’. Learn more here.

About Evan Christenson

Evan Christenson is a burnt out Cat 1 road racer from San Diego who is transitioning to a different side of the sport. He studies Mathematics at UCLA and writes in his free time. Read more about what he’s up to on his website, Evan.Bike, or on Instagram @evanchristenson.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.