Eastern Divide Trail (S3): Lupine

Distance

639 Mi.

(1,028 KM)Days

11

% Unpaved

77%

% Singletrack

3%

% Rideable (time)

99%

Total Ascent

43,500'

(13,259 M)High Point

3,010'

(917 M)Difficulty (1-10)

6?

- 4Climbing Scale Fair68 FT/MI (13 M/KM)

- 5Technical Difficulty Moderate

- 7Physical Demand Difficult

- 6Resupply & Logistics Moderate

Contributed By

Logan Watts

Pedaling Nowhere

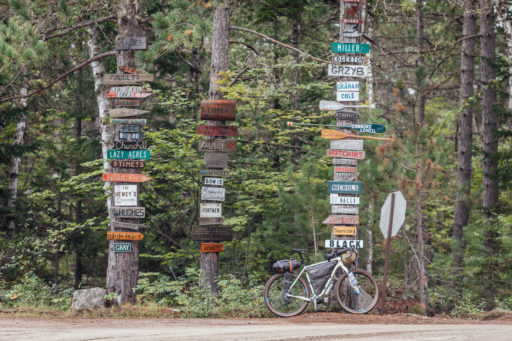

Segment 3 of the Eastern Divide Trail, aka Lupine, is named after a distinctive flowering plant that carpets the landscape throughout the eastern United States, spanning from New England to Florida. A native species to Maine named Sundial Lupine (Lupinus perennis) has been steadily declining in number and range since the Industrial Revolution and is now scarce in the state.

While that story alone seems appropriate to denote the beginning of the US portion of the Eastern Divide Trail—a southward traverse through the remaining wildlands within a region of the country heavily marked by industry and density—the etymology of the word Lupine is even more fitting. Latin lupīnus “wolflike” (from lupus “wolf”) better conjures the ambience of EDT3, a purpose-made bikepacking route that rolls through landscapes defined by enchanting evergreen forests, rugged mountains, clear and bristling streams, and secluded lakes where the haunting sound of the loon echoes that of Canis lupus.

Remote landscapes aside, the 630-mile EDT3 takes in a variety of unique places, geographical features, and regional highlights that make it a one-of-a-kind bikepacking route that’s worth riding as either a part of the entire EDT or on its own. Those include several amazing parks and ranges, such as Maine’s sprawling Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument and Baxter State Park, New Hampshire’s majestic White Mountains and Presidential Peaks, and the beautiful Green Mountains of Vermont.

The route also rolls through countless charming towns and unique places of interest, including Appalachian Trail communities like Monson, Maine, as well as many historic landmarks, beautiful covered bridges, and a sampling of Vermont’s finest breweries and establishments representative of their incredible craft beer scene. Though Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont comprise a continuous region of northern New England, they each have a quite different character from one another. All in all, there’s a lot packed into this 10-day ride that might just encourage even the most committed riders to stop and smell the flowers. For a complete rundown of the route, find a suggested itinerary under Trail Notes.

Lay of the Land

By Tsinnijinnie Russell (@tsinbean)

The term “Abenaki” has been widely used to describe Wôbanaki tribal communities in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and southeastern Quebec. This confederation of people were the original inhabitants of the Northeast. Abenaki is a mistranslation and mispronunciation of Wôban-aki, the word used to describe the land and people. It means “the People of the Dawnland,” “the First Light,” or simply “of the East.” Today, the Wôbanaki, or Wabanaki, nations are understood as Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, Penobscot, Mi’kmaq, and Abenaki.

Mali Obomsawin has eloquently written about the Wabanaki and their communities in the area, describing how the Wabanaki communities traditionally identify themselves by the rivers they traveled along, or the permanent villages located along the rivers. The Penobscot and Kennebec exemplify this naming convention. Wôbanaki place names typically describe landforms of significance and the activities in those areas. For instance, Pαnawάhpskek (Penobscot) means “where the rocks widen” and refers to Verona Island, where a permanent community lived at the mouth of the Penobscot River.

The political, social, and physical organization of the Wabanaki was confusing to the English and has resulted in a mixed historiographic record. Western scholarship struggles to conceptualize traditional Wabanaki lifeways because they do not fit into a modern idea of a “tribe” or “town.” In reality, the Wabanaki were in constant movement throughout the year, and Wabanaki communities were fluid; this speaks to “their deep knowledge” of the land and “the strength of their kinship networks” (Mali Obomsawin, The Wabanaki of the Kennebec River, 2020).

The Wôbanaki Confederacy was the primary coalition in the area with cultural and familial ties. Its original core consisted of closely related Abenaki tribal communities. This later extended to similarly clustered Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and eventually numerous Mi’kmaq bands. This group grew and gradually developed a close cultural relationship and is now referred to as the Wôbanaki Confederacy. The tribes making up the Wôbanaki Confederacy first made European contact in the early 1600s, with French explorers on the Maine coast reporting an early confederacy with a paramount chief named Bashabes. Bashabes headed Mawooshen, an alliance of more than 20 villages located between Cape Neddick and Schoodic Point.

Using oral histories and reports from colonial sources, it is suggested that the Wôbanaki Confederacy was formally formed in the early 1680s as a response to disease, war, and colonization. The Wôbanaki Confederacy remained a potent political force in the region through the end of the American Revolutionary War. Following the war, their territory and political power was split by the international boundaries, and they gradually lost power. In 1870, the cross-border alliance upheld by the Wôbanaki Confederacy had collapsed due to outside pressures from powerful state and federal agencies, particularly the state of Maine. The confederacy was revived in 1993 and now includes the Metis Nation. Today, the tribes continue to cultivate relationships with the land and keep their traditions and culture alive.

Find more details about specific places in the Whereabouts tab below.

Like all of the EDT segments, Lupine consists of a wide variety of surface types. However, EDT3 boasts the highest percentage of unpaved surfaces out of all the US segments. This largely owes to an exorbitant concentration of logging roads in Maine and an abnormally high percentage of gravel roads in Vermont—the highest in the lower 48. The smorgasbord of surfaces on EDT3 range from chunky ATV tracks to smooth gravel roller coaster roads and from twisty New England singletrack to quiet countryside backroads and from “grass up the middle” rail trails to Vermont’s notorious Class IV roads. This route has it all in a well-timed mix that’s enough to serve up a challenge but remains blissful and rewarding throughout.

Route Difficulty

Physical Demand: 7 • Technical Challenge: 5 • Resupply/Logistics: 6

From a technical point of view, there aren’t a lot of extended difficult sections. There are a few stints on rugged ATV/jeep and “Class IV” roads, which keeps it interesting and may lead to a couple of hike-a-bikes, depending on your abilities, but nothing that goes overboard for a long period of time. There are also a couple of short stretches on classic New England singletrack, which is generally more twisty and flowing than it is technical.

There are a few big climbs on this route, with other sections punctuated by challenging ups and downs. Examples include the climb up to Jefferson Notch in New Hampshire and Vermont’s fabled Lincoln Gap. Both are long and sharp, with the latter being one of the steepest grades in New England. All in, there is a good mix of mellow riding and sections that offer some challenging climbs, but the physical challenge shouldn’t be underestimated, which is why we gave it a 7 out of 10. There are plenty of resupply options on route, but we assigned it a 6 out of 10 because of the logistics required to get to the beginning of the route; see Must Know tab for details.

Route Development

EDT3 was designed and conceived by Logan Watts with assistance from Joe Cruz, particularly in Vermont. Admittedly, creating a workable route in Maine was one of the most challenging segments to stitch together out of the whole EDT, given the especially complex nature of Maine’s lands and roads—namely, the lack of public lands and the multi-owner/multi-use North Maine Woods, which you can read more about here. We couldn’t have done it without the help of Erik daSilva from Bicycle Coalition of Maine (bikemaine.org) who helped find a bike-legal route from Millinocket to Monson around the complex North Maine Woods lands and provided insight into the AMC (Appalachian Mountain Club) land. Additional thanks and credit to Zander Martin for providing a better option through the Gale River area in New Hampshire, as well as suggestions and improvements in the Carrabassett Valley and elsewhere. Thanks also to Caitrin Maloney for suggestions and improvements in Vermont leading up to Poultney.

GPX download (link below) includes a detailed set of waypoints. Please keep personal copies set to private on RWGPS and other platforms. The Eastern Divide Trail was made possible by our Bikepacking Collective members. Consider joining to support the creation and free distribution of thoughtfully planned and documented bikepacking routes like this one.

Submit Route Alert

As the leading creator and publisher of bikepacking routes, BIKEPACKING.com endeavors to maintain, improve, and advocate for our growing network of bikepacking routes all over the world. As such, our editorial team, route creators, and Route Stewards serve as mediators for route improvements and opportunities for connectivity, conservation, and community growth around these routes. To facilitate these efforts, we rely on our Bikepacking Collective and the greater bikepacking community to call attention to critical issues and opportunities that are discovered while riding these routes. If you have a vital issue or opportunity regarding this route that pertains to one of the subjects below, please let us know:

Highlights

Whereabouts

Must Know

Camping

Food/H2O

Trail Notes

- Views of Mount Katahdin and a beautiful ride through Baxter State Park on dirt and gravel roads

- Taking advantage of the amenities and community in Appalachian Trail towns such as Millinocket and Monson, Maine

- Spotting moose and other wildlife along Maine’s infinite network of forested roads

- The countless scenic lakes and streams in the north woods forests across Maine

- Hidden gems like the Katahdin Iron Works historical site and Borestone Mountain Audubon Sanctuary

- Vistas of the White Mountains and the Presidential Peaks as you make your way into New Hampshire

- Climbing up to Jefferson Notch and catching views of the scree-filled flanks of Mount Jefferson and Mount Washington

- Seeing historic covered bridges such as the Bath Village Covered Bridge along the scenic Ammonoosuc Rail Trail

- Taking in a few snippets of New England’s finest singletrack, including the Carrabassett Valley in Maine and several networks in New Hampshire and Vermont

- Getting a taste of Vermont’s infamous Class IV roads!

- Sampling Vermont’s craft beer scene; the segment shares 50 miles with the Vermont Gravel Growler and passes by the Three Penny in Montpelier and Breweries such as Good Measure in Northfield and Lawson’s in Waitsfield

- High fives or a self pat on the back for making it up and over Lincoln Gap, the highest paved pass in Vermont and one of the steepest in New England

- Vermont’s ultra-quaint towns and villages, including a finish in Poultney, home of Tanglefoot and Analog Cycles, an eclectic bike shop dedicated to ATBing and bikepacking

Whereabouts describes a list of places and things that are a part of this route as a means to understanding its history. With research and writing by Tsinnijinnie Russell (@tsinbean).

pin Mile 61

Baxter State Park and Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument (KW&W)

Conservationist Percival Baxter helped to create what is now Baxter State Park (BSP) after summiting Katahdin in 1920 during times of unprecedented land exploitation in the region. Much later, in 2011, Roxanne Quimby—founder of Burt’s Bees—and her son Lucas St. Clair were instrumental in the creation of Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument (KW&W). Both entities now operate to ensure access to the wilderness in perpetuity and should each be credited with working hard to protect these lands for public use in a state where 94% of the land is privately owned.

It’s said to be “the center of the universe for the Wôbanaki” and also a model for modern preservation. Baxter State Park is an anomaly among parks, and Katahdin Woods and Waters is Maine’s newest addition to the National Park System. Both work to limit impact while allowing access to this beautiful area.

pin Mile 96

Mount Katahdin

Mount Katahdin is the tallest mountain in Maine, reaching 5,269 feet in elevation. It is a steep, high massif formed from a granite intrusion weathered to the surface and is the centerpiece of Baxter State Park and the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail. Katahdin is a Penobscot name translating to “The Greatest Mountain.” The mountain represents the beginning of life, and the Penobscot often lived in the regions surrounding the mountain, fishing and hunting. The Penobscot believed that an evil spirit, called Pamola “he curses on the mountain,” is a spirit who resides on the mountain during the summertime.

pin Mile 112

Millinocket Lake

Millinocket is an Abenaki word meaning “the land of many islands.” This area has been continuously inhabited by Indigenous peoples for over 10,000 years. The first European settler in what would eventually become the town of Millinocket arrived in 1829. In 1894, the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad finished a line to Houlton, Maine, providing rail service to the area. The remote, forested area was turned into lumber for paper mills. The Great Northern Paper Company constructed their mill in 1899 and attracted large numbers of immigrants from Italy, Poland, Finland, Lithuania, and Hungary. This would become the largest paper mill in the world for a period.

pin Mile 263

Kwenebek(i) (Kennebec River)

Kwenebek(i) means “deep river.” This river and its watersheds are home to the Wabanaki of western Maine, and it’s one of Maine’s most important resources. From the 1300s until the 1700s, it was the easternmost stretch of land where corn could be cultivated. Its basin is located in west central Maine and drains 5,893 square miles. The river originates at Mozôdupi Nebes (Moosehead Lake), home to Mount Kineo, “Sharp Peak.” The river runs 170 miles from Mozôdupi Nebes to the Atlantic Ocean. The upper basin spans from Mozôdupi Nebes (Moosehead Lake) to Waterville and the lower spans from Waterville to the ocean.

Using the Kennebec river, you could access the St. Lawrence, Androscoggin, Allagash, St. John, Sebasticook, Penobscot, Machias, and the Saint Croix Rivers, as well as reaching the open ocean. “Narantsouak,” anglicized as “Norridgewock,” signifies “at the confluence of rivers” and was a large tribal community living in the area between where the Sandy River and Carrabassett River meet the Kennebec. As a riverine people, the Narantsouak was both a central location and the center of their world with deep spiritual significance.

pin Mile 296

Carrabassett

Carrabassett is the name of a river, valley, and town located in Franklin County. The Abenaki term is of uncertain meaning but may translate as “small moose place” or “sturgeon place.” This area has been home to Indigenous people for up to 13,000 years. The ancestors of the Wabanaki were the first people to arrive in the area, soon after the glaciers receded. There is archaeological evidence of stone tools mined in eastern New York, possibly from the late ice age. Fired clay pottery have also been found and may be up to 2,000 years old. Europeans introduced diseases between 1500-1600 AD that spread due to the existing trade networks. By 1730, many of the Indigenous inhabitants of western Maine had died. Today, the five federally recognized tribes of Maine (Aroostook Band of MicMacs, Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, Passamaquoddy Tribe of Indian Township, Passamaquoddy Tribe at Pleasant Point, and the Penobscot Nation) are all located in Eastern Maine.

pin Mile 335

Oquossoc (Rangeley Lake)

This name for the town on Rangeley Lake was the name for Rangeley Lake itself. The translation is not clear, though. It may refer to “a blue slender trout” or “place of the oquassa trout,” but it may instead mean “place on the other side of a little stream.” The lake serves as the one of the main headwaters for the Androscoggin Watershed, feeding Mooselookmeguntic, Upper and Lower Richardson, and Umbagog Lakes, ultimately feeding into the Androscoggin River and Kennebec River that feed into the Atlantic Ocean. The area did not see permanent European settlements until 1810. The area served as a tourist destination for fishing and was featured in regional travel guides put out by railroad companies.

pin Mile 350

Mooselookmeguntic Lake

“Portage to the moose feeding place” or “moose feeding under big trees.” This river is a part of the Androscoggin River watershed and is just a few miles from the Appalachian Trail. The Cupsuptic River flows into Cupsuptic Lake, which is directly connected with the northern part of Mooselookmeguntic Lake. The Rangeley River and Kennebago River both flow into the northeastern part of the lake. This lake flows southeast into Upper Richardson Lake. The construction of the “Upper Dam” between Upper Richardson and Mooselookmeguntic Lake caused Mooselookemeguntic’s water level to rise by 14 feet, thus causing it to join with Cupsuptic Lake to form a reservoir. Prior to the building of the dam, the two lakes were separate. The lake has a large number of tributaries that serve as excellent spawning and nursery areas for trout and salmon. The lake is a part of the Rangeley Lake area.

pin Mile 389

Mahoosuc Range

This is the name for a mountain range located in Coos County, New Hampshire, and Oxford County, Maine, and also for a notch, or deep gap, in the range. It may be Abenaki for “abode of hungry animals,” probably referring to the many caves that would make for good dens. The Old Speck Mountain is the highest peak at 4,170 feet. Home to one of the most difficult sections of the Appalachian Trail, the Mahoosuc Notch. Due to heavy logging, there are very few stands of old growth forest remaining in the range, though there is a section north of Mahoosuc Notch containing old beech, birch, and maple trees. Indigenous people, primarily the tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy and the Anasagunticook (Androscoggin), have lived in the area for centuries. European settlers began to push inward from the coast more rapidly after the Revolutionary War. In the 1850s, the railroad brought tourism to the area, and in 1937, the completion of the Appalachian Trail spurred another increase of visitors into the area.

pin Mile 405

Mount Jasper

Located in Berlin, New Hampshire,. the flow bands of rhyolite stone are unique to Mt. Jasper and possesses qualities that made it desirable for stone tool makers, users, and traders. There are documented Indigenous mining sites found here showing the use of lithic materials making stone materials as early as 9,000 years ago. The tools were found on the mountain and also up to hundreds of miles away, illustrating the vibrant trading among the Indigenous people of the area.

pin Mile 429

Kawdahkwaj (Mount Washington)

Kawdahkwaj, possible translation: “Hidden Mountain in the Clouds.” Agiocochook possible translation: “Home of the Great Spirit or Mother Goddess of the Storm.” Waumbik possible translation: “White Rocks.” The largest mountain in New Hampshire and the Northeastern U.S. at 6,288 feet. For 76 years, it held the record for the fastest surface wind gust in the world at 231 mph. The first European ascent of the mountain was performed in June of 1642 by Darby Field accompanied by two Native American guides. It is said that Field wanted to prove to the local Abenaki Chief, Passaconaway, that he was not subject to the same rules as the Indigenous peoples, who did not climb the summit of the mountain believed to be the realm of divine powers. By climbing the mountain, Field dismissed these Indigenous beliefs and assisted the colonists’ northern expansion.

pin Mile 440

Wawobadenik (White Mountains)

“To the Place of the high white (or crystal-mica) mountains,” or “at the place of the white mountains” is a part of the cultural patrimony of Abenaki Penacook and other Wabanaki peoples. The greater range contains Mount Washington, the highest peak in the Northeastern U.S., as well as the Franconia Range, Sandwich Range, Carter-Moriah Range, Kingsman Range, and Mahoosuc Range. The colonial name most likely refers to the often snow-capped peaks or the mica-laden granite of the summits, which looks white. The U-shaped form and various notches and mountain passes were created by glaciation.

pin Mile 460

Mount Cannon

Rock formation known as “Stone Face” or “The Old Man on the Mountain,” this rock formation created an image of a person from a distance, which they perceived as being that of a male. Shaped by the water inside cracks in the granite bedrock, which repeatedly froze and thawed following the retreat of glaciers about 12,000 years ago, this formation collapsed in 2003. Despite its deep historical roots, the Old Man was an example of Euro-American settlers claiming the landscape as their own—a trophy of the conquest—whereby all Native American place-associations and meanings have been transformed into a commercial sightseeing and tourism and commodified symbol of the Granite state’s identity.

pin Mile 483

Bath, New Hampshire

State historical marker. Settled in 1766 by Jaasiel Harriman, whose cabin was near the Great Rock. His nine-year-old daughter Mercy carried dirt in her apron to the top of this unique rock formation. Here, she planted corn, pumpkins, and cucumbers, making the first garden in town. Three well-preserved covered bridges can be found here. Among its many fine homes is the Federal mansion built by Moses P. Payson in 1810.

pin Mile 488

Kwenitekw (Connecticut River)

Abenaki name that means “long flow (river).” Kwenitekw is 410 miles long and passes through four states, starting at the northern tip of New Hampshire along the Quebec border and flowing through Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. The river emerged after the end of the last ice age and has always drawn people for use of navigation and an extension of trading routes, as well as for fertile hunting and farming lands. Archaeological evidence found along the river dates back to being over 5,000 years old. As riverine people, the Wabanaki view rivers as a paradigm of indigeneity. Bands of Wabanaki people gained their name from the river they lived along and their communities, often found at confluences, and served as nerves connecting a network of relations facilitated by the rivers.

In the early 1600s, Dutch and English settlers established forts along the river in order to trade with the Indigenous people. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, the river grew in importance for settlers as a way to gain access to pelts and other goods. Industrialization in the U.S. during the 18th century exacerbated overuse issues brought upon earlier by logging and farming. The natural flow of the river was diverted by industry to generate power and Kwenitekw. Agricultural run-off from the farming and tobacco industry added pollution to the river, and after WWII, the introduction of new chemical dyes and pesticides toxified the river.

Rather than viewing the river as a connecting force provided in countless ways, settlers viewed the river simply as a resource to extract wealth from and turned it from a pristine waterway into a toxic cesspool. In 1973, the Connecticut River Gateway Commission was created to monitor standards for development of riverfront land and to help redevelop the surrounding area to attract wildlife back to the area around the river.

pin Mile 500

On Maple Syrup

Depictions of maple syrup production and products are often laden with colonial signifiers. Bottles with pictures of log cabins in pastoral scenes with (usually) white farmers dressed in plaid collecting sap from tin buckets. This depiction of maple syrup discounts the Indigenous people who perfected and passed along the knowledge of maple sugaring to European colonists. Alexander W. Cotnoir of the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation writes about how Abenaki people of Vermont have been utilizing a multi-step process to collect and condense sugar maple sap for generations. The first written account comes from Jesuit Sebastien Rasle in 1722, who writes about the women of the Kennebec working to collect sap from bark and boil it down to obtain sugar.

That Indigenous women led the operation speaks to the differences in Indigenous production versus the male-dominated European production process. The Abenaki would collect sap in clay or woven birch-bark sap baskets placed at the feet of trees and left to freeze. Freezing the sap in the basket would act as a reverse osmosis because it allowed them to reduce water by removing the frozen ice that formed on the top. The sap was then poured into clay and soapstone pots or suspended above the flame in order to boil.

The Abenaki language also highlights the importance of maple; the word “mskwajo” distinguishes birch bark baskets used for gathering sap from other baskets. Pkwamha is a traditional word that refers to the process of gathering sap. They also refer to the spring season, when sap is harvested, as “Sogalikas,” which literally translates to “time of maple sugar making.” The harvesting season would also serve as a time for Abenaki communities to gather and pass along knowledge and oral histories. To this day, the Abenaki keep their sugaring traditions alive by producing maple syrup each spring. This allows them to cultivate a working relationship with the land and practice their language, while also giving thanks to the woods for sustaining their communities for generations past, present, and future.

pin Mile 592

Wnekikwisibo (Otter Creek)

At 112 miles, this is the longest river that is contained entirely within Vermont, and the route crosses it at the Hammond Covered Bridge. In the Green Mountain National Forest, the river rises on the western slopes of Mt. Tabor in Peru, Vermont, and flows northward, eventually emptying into Lake Champlain. Wnekikwisibo, “Otter river /creek,” remains one of the most intact and wide floodplains in Vermont. The river has been used by the Indigenous people of the area as a resource and as a means to facilitate trade for centuries. It was referred to as the “Indian road” by early settlers because of its importance to navigating Wabenaki, Omàmiwininiwak (Algonquin), and Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) settlements in the region. The river was used as a means for French settlers to move inland, settling at the City of Vergennes and constructing a fort at Crown Point in 1731. In the 1800s, hydropower facilities were built for industrial purposes on the river in Rutland, Proctor, Brandon, Middlebury, Weybridge, and Vergennes.

pin Mile 609

Green Mountains and Green Mountain National Forest

Skanontkaraksèn:ke “Where the cliffs are clumsy”, or Skanontkaraksèn:ke tsi iononténion/ionontahrónnion “The mountains where the cliffs are clumsy.” The Green Mountains are among the oldest mountains in North America, with the geologic age of some rocks dating back over a billion years. The name for the state, Vermont, is derived from the French words “vert” (green) and “mont” (mountain). The area was colonized by primarily British settlers, most extensively after the end of the Revolutionary War. Because of this, many of the features and landscapes visible in the park are from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The park itself was established in 1932 as a response to overlogging, fire, and flooding of the forest. Many of the names come from British settlers who followed geographic naming conventions that preferred Old or New English localities, notable individuals, and wealthy patrons over Indigenous naming conventions that were less abstract and had more to do with the features themselves. Indigenous names in the area reflect a direct connection between the people and the land. Even though the names of many features have been lost, the Wabanaki people can still reconnect to the knowledge of their mountain relatives by nurturing proper relationships with the land itself.

WHEN TO GO

- The best time to ride Segment 3 is from mid-August through mid-October, although it’s largely rideable from June through October.

- How early in the summer it can be ridden depends on the amount of snowfall the region receives the winter prior and how quickly it warms up and melts.

- October can be iffy, too; depending on local temperatures and weather patterns, there could be early snowfall and colder temperatures.

- If you’re sensitive to biting insects, we’d recommend not riding this route mid-June to mid-August. The deer flies (aka horse flies or moose flies) are bad during that time frame, and they thrive in wooded areas along gravel roads. They can easily keep up with any rider and even bite through fitted clothing while you’re riding. Mid-August into the fall is the best time of year to visit these trails/roads. If you do ride this segment during that window, consider loose-fitting clothing, insect repellent, and even a head net. When we rode it in mid-late August, we didn’t have any issues.

LOGISTICS

- If you’re section riding or shuttling this route, there is legal, non-metered street parking at the southern terminus in Poultney, Vermont, on Main Street. Locals have recommended that it’s probably the best bet for a place to leave a vehicle and is generally safe.

- Castleton, Vermont, just north of Poultney, has an Amtrak station that services the Ethan Allen Express, a train that goes to Albany and NYC, cities with major airports.

- The northern terminus is a little more tricky, but the Cyr Bus Line runs every day from Bangor to Houlton and points north, and happily takes bikes in the hold free of charge. It meets the arrival of the Concord Trailways bus in Bangor, so you can easily connect from Portland, ME and Boston, MA. There are major airports in Boston, Portland, and Bangor. You could also consider starting in Millinocket, Maine, which has a hostel and shuttle service that caters to Appalachian Trail through-hikers. Another option—and how we accomplished our scouting mission—is to rent a one-way Uhaul in Bangor, which can be dropped off in Millinocket.

DANGERS & ANNOYANCES

- Many of the gravel roads in Maine are within private lands undergoing active logging operations; please yield to all logging traffic. Be super predictable by pulling off to the side of the road, giving the trucks plenty of space, and waving a friendly hello as the truck drives past. We’ve never had an issue with truckers and friendly waves always get returned. The key to getting more lands open to us in the future lies here.

- See “when to ride” about biting insects.

- Many parts of this route are in black bear country, especially in the more remote sections. It’s advisable to tie up your food at night while camping. Find details on the PCT method here.

- It’s also not uncommon to see moose in these areas. Know how to properly act in such encounters. You can find some information at Outdoors.org and do your own research as well.

- Some of the route is within cell service, although there are quite a few places without. You might consider bringing a satellite tracker or emergency beacon in case of injury or catastrophic failure.

- While much of this route uses gravel and relatively low-traffic roads, there are a few spots worthy of extra caution. Namely,there is still active logging in and around North Maine Woods, as mentioned. As with any cycling outing, cars pose a threat. Wear bright colors and bring a rear blinker light.

- Additionally, there is hunting within national and state forests, wildlife management areas, and other public and private lands. Be sure to do your research on hunting seasons in these areas before setting out. And bring bright clothing, including a hi-viz orange vest if riding through any of them during hunting season.

WHAT BIKE?

- The best bike for this segment, as well as the entire Eastern Divide Trail, is an ATB or Tour Divide-style bike. For drop-bar aficionados, the Salsa Fargo and Cutthroat come to mind, or the Surly Ghost Grappler or Tumbleweed Stargazer. For those who prefer flat bars, any moderate hardtail or rigid 29er would be great, such as the Surly Ogre or Bridge Club, Salsa Timberjack, or Otso Fenrir. Find our writeup on the subject here.

- Considering the bullet point above, this segment has a few rough sections. Tires that are 2.35” or larger are highly recommended for comfort and good times. Plus, you might just want to dig into more New England singletrack along the way.

- As mentioned in the route difficulty section, there are many steep sharp climbs through this route segment. They are often relatively short, but the cumulative effect of many in a row is notable. We recommend forgiving gearing and an easy bailout gear.

- We like fast-rolling, ~2.4” XC rubber for this ride. Tires that folks like for the Tour Divide work well. The Maxxis Ikon or Rekon Race, Teravail Ehline, and Vittoria Mezcal are all tires we’ve used while scouting.

- There aren’t too many significant bike shops on route, aside from Analog Cycles at the southern terminus in Poultney, Vermont. There are a few slightly off route, such as Vermont Bicycle Shop southeast of Montpelier in Barre, Bicycle Express between Montpelier and Waterbury, Frog Hollow Bikes in Middlebury, and a repair shop called Stark Mountain in Waitsfield. There is also a small rental shop in the Carrabassett Valley in Maine.

- Segment 3 begins in Houlton, Maine. There is a motor lodge just north of town, on route, across I-95.

- There are campgrounds and established campsites within public and private forest land throughout the route. Many prominent options are noted in the downloadable GPX file, but there are more. However, it’s advised to do your own research based on your pace.

- There aren’t any prolonged stretches without camping options on this route, but there are stretches without established campsites. If wild camping is a must, we recommend setting up after dusk and leaving at dawn. There are remote stretches of forest and options to camp out of sight within wooded areas throughout. Churches, parks, community centers, and other public places are usually safe options, too, but use your own judgment. As always, leave no trace.

- There are hotels/motels/lodging in Millinocket, Monson, and Rangely, Maine; Gorham and Franconia, New Hampshire; and Montpelier, Vermont. There are also options slightly off-route here and there, such as in the beautiful Mad River Valley between Waitsfield and Warren, Vermont, as well as in Rutland, Vermont

- Segment 3 finishes in Poultney, Vermont, which is home to Analog Cycles and Tanglefoot. Camping is available at Analog’s old HQ at 181 Hillside Rd, which has about 15 free bike camping spots. It’s rustic with no water and no facilities, but it’s within a 1/4 mile of the general store, which is open (roughly) 7-6 Tues-Sat, and two miles from downtown Poultney. Analog asks that riders email them at analogcycles@gmail.com to give notice that they’re coming through, and pack out whatever trash and poo they generate.

- Filterable water is available throughout the route. We didn’t find any areas where water sources are an issue.

- There are a fair number of resupply options on this route, as noted in the POIs of the downloadable GPX file. The most significant and well-stocked towns include Millinocket, Monson, and Rangely, Maine; Berlin, Franconia, and Woodsville, New Hampshire; and Montpelier, Vermont. There are also options slightly off-route here and there, such as Waitsfield, Vermont.

- There are several shops that cater to Appalachian Trail through-hikers along the way, such as the general store in Monson that stocks freeze-dried meals and other packable food items.

- There several great places to eat and drink along this route. In New Hampshire, check out Exile Burrito in Berlin and Big Day slightly off route in Gorham. There are tons of options in Vermont; a few that stand out include the Three Penny Taproom in Montpelier, Good Measure in Northfield, and several excellent spots in the Mad River Valley, including the Warren Store (great sandwiches), Mad Taco, and Lawson’s Finest Liquids, one of the best breweries in Vermont.

- There are also a lot of great markets and general stores, all marked on the final GPX.

Here is an example itinerary based on 50-75 mile days. This is a solid baseline that a fit thru-rider carrying a medium-light load might consider as a relatively challenging bikepacking itinerary.

location Houlton-Matagamon Wilderness

Day 1 (61 mi +4,100 ft)

EDT3 begins in the border town of Houlton, Maine. It starts with several linked back roads as it begins a westward traverse. The route turns to gravel then more rugged dirt roads as it rolls across the southern flank of Mt. Chase, a prominent peak on the landscape. Shortly thereafter, the route threads upper and lower Shin Pond, where you can find Shin Pond Village. This family-operated recreational facility offers campsites, cottages, a general store, restaurant, bar, gift shop, laundromat, and more. The next 15 miles are relatively smooth gravel to get to the Matagamon Wilderness Campground, a facility tucked in on the shore of the East Branch of the Penobscot River that offers 36 primitive campsites with a fire ring and picnic table and a coin-operated shower house.

location Matagamon Wilderness-Millinocket

Day 2 (64 mi +3,200 ft)

Leaving the Matagamon Wilderness Campground, riders will be treated to a beautiful traverse of Baxter State Park. The route begins to climb up the dirt Park Tote Road after leaving the banks of Grand Lake and then joins the aptly named Perimeter Road as it turns south along the western flanks of North Brother, Hamlin Peak, and Mount Katahdin. If you wish to linger a while in the park, and perhaps hike the peak of Katahdin, consider a stay at Katahdin Stream Campground, where the route intersects with the Appalachian Trail near its northern terminus.

After the park gatehouse at the southern entrance/exit, the route joins a paved road and descends to Millinocket Lake, where riders get a taste of the Katahdin Area Trails (KAT), a relatively new network of sustainable purpose-built singletrack mountain bike trails on Hammond Ridge. If you have the time, check out some of the other trails in the network. You can find camping and lodging nearby, or roll on to Millinocket, where there’s a hostel and campground near town, as well as resupply options and restaurants.

location Millinocket-Camp Pond

Day 3 (67 mi +4,000 ft)

Leaving Millinocket, the route follows State Road 11 for about 10 miles. While 11 is generally quiet with little traffic, you may have the occasional logging truck pass by. They’ll usually give you a wide berth, but be sure to use lights and wear bright clothing. Keep an eye out for moose on this road, too. I spotted one on the roadside that quickly darted back into the brush as I passed. After jumping off 11, the route joins up with Cedar Lake Road and heads into the woods past Cedar Lake and Caribou Bog before passing several other lakes, including Endless Lake, where there’s a campsite. The route will ultimately lead to pavement as it skirts the small town of Brownville. There, you can find a lone convenience store if you need any supplies.

From Brownville, the route runs north along the Pleasant River and eventually intersects with Ore Mountain Road and Katahdin Iron Works Road. Make sure to cross the bridge and explore the old Katahdin Iron Works site and walk around several old stone structures from the blast furnace and iron forge that was in operation there during the 19th century (details here). This itinerary is based on making it a few more miles to Camp Pond, where there are a couple of side roads around mile 189. While there aren’t any notable established camp sites, there are places where you could bivy along the roadside. If you have 20 more miles in your legs, you could also make it to Monson, where there’s an AT hiker hostel, restaurants, and a good general store for resupply.

location Camp Pond-Lake Moxie

Day 4 (55 mi +4,400 ft)

From Camp Pond, the route rolls past Borestone Mountain Audubon Sanctuary, a 1,600-acre parcel in Maine’s Hundred Mile Wilderness region that offers a rare older forest, three mountaintop ponds (Sunrise, Midday, and Sunset), exposed granite crags, and panoramic views. There’s a hiking trail that goes to the top if you have time (more here). The route crosses Big Wilson Falls before turning to a paved road leading into Monson, a nice little town that’s the last stop for northbound Appalachian Trail hikers before they head into the fabled Hundred Mile Wilderness.

There are two mainstay establishments in town, Shaw’s Hiker Hostel and the Monson General Store, both catering to hikers (and good for bikepackers). Find all kinds of packable food in the General Store and stay a night at Shaw’s if you want to trade tales with AT hikers. Continuing on, the route joins an ATV road outside of Monson before joining a more established road in Shirley. After a little more chunky climbing, rolling gravel awaits with views of the mountains as it heads west. The route takes a fast descent down to Lake Moxie, about a dozen miles from Shirley, and begins a southbound ride along this beautiful lake. The quiet gravel road offers viewpoints throughout. There is an official pay campground at the north end of the lake and a primitive roadside site at the southern end.

location Lake Moxie-Stratton Brook Pond

Day 5 (60 mi +3,800 ft)

Lupine continues south after Moxie, rolling toward Bingham, where there’s a general store and a couple of shops. From Bingham, the route winds north along Wyman Lake, then turns west toward Flagstaff Lake. There are a couple of decent roadside campsites in this area and some big views of Flagstaff and the surrounding mountains. There’s a mix of pavement, gravel, rough doubletrack, and a little singletrack that stitches together a route into the Carrabassett Valley, a mountain bike and outdoor destination. There are some stores and restaurants in Carrabassett, too. A climb up rail grade and then a stretch on swervy singletrack takes riders into the Bigelow Preserve and Stratton Brook, where there’s an established campsite.

location Stratton Brook Pond-South Arm Campground

Day 6 (62 mi +4,100 ft)

The track gets a little rough after Stratton Brook, but it’s a relatively short distance into the town of Stratton. There are resupply options in town before you get on an ATV track that leads over the gap just south of Quill Hill. If you have the time and energy, climb up to the Quill Hill lookout for 365° views of the surrounding mountains. A fast descent on the other side leads to Redington Road and Stratton Road before jumping on a recreational path that heads to Rangeley, a touristic town with restaurants, lodging, and shops. From town, the route runs along the beautiful Rangeley Lake and the tongue-twisting Mooselookmeguntic Lake before arriving at South Arm Campground. The campground is on the banks of Richardson Lake on a peninsula with 65 wooded sites for RVs, trailers, or tents.

location South Arm Campground-Mount Jefferson

Day 7 (59 mi +4,200 ft)

The next day begins with a steady up and down out of South Arm, eventually crossing the Dead Cambridge River along the Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge. After Andover Road, expect to catch a few views of the White Mountains as you begin a hearty climb along the Mahoosuc Range paralleling the Appalachian Trail. The name Mahoosuc is an Abenaki word for “abode of hungry animals,” probably referring to the many caves in the area that made good dens. Eventually, you’ll enter New Hampshire along a fast gravel road as the route leads into the town of Berlin. Grab lunch at Exile Burrito and any supplies you might need in town, although there’s also a brewery and additional options slightly off route in Gorham a little bit down the road. The route follows the Presidential Rail Trail through this zone before mounting a sharp ascent up to Jefferson Notch, where you can take in views of Mount Jefferson, part of the Presidential Range of the White Mountains and the third-highest mountain in the state. There are a few roadside campsites on the way up, although they may be busy on the weekend and/or high season.

location Mount Jefferson-Ricker Pond State Park

Day 8 (75 mi +4,900 ft)

From Mount Jefferson, there are a couple of viewpoints where you can catch a glimpse of Mount Washington, the highest peak in the Northeastern United States at 6,288 feet. After a fast descent, you’ll join the bridal path next to the Ammonoosuc River, where there are some great swimming holes. A quick jaunt on the paved road takes you into Bretton Woods, where you can fuel up at the deli. From Bretton Woods, the route uses a mix of gravel, snowmobile tracks, and backroads to skirt the White Mountains en route to Cannon Ski Resort, where a singletrack descent will lead into Franconia. There’s a quick climb and descent next that connects to the scenic Ammonoosuc Rail Trail. The route passes the historic Bath Covered Bridge shortly thereafter and continues on the ART until Woodsville, where there are several resupply options. After Woodsville, it continues on a mix of pavement and rail trail toward Groton Pond, where there are several state park camping options, including Stillwater and Ricker Pond State Park. Both offer paid camping options, and there are more in the area.

location Ricker Pond State Park-Waitsfield, VT

Day 9 (53 mi +4,600 ft)

The route continues on rail grade and backroads until you get close to Montpelier, where big wide-open farm road gravel climbs commence. Make sure to stop at Three Penny Taproom in Montpelier for a sandwich and beer. After Montpelier, EDT3 climbs up and over the north saddle of Irish Hill and takes in some nice singletrack before connecting with the Darling Road, a rugged Class IV descent toward Northfield. Stop at Good Measure for a refreshment if you’d like. The route follows a backroad climb out of Northfield before connecting with gravel and traversing the eastern side of the Northfield Mountains.

After clearing Moretown Gap, the route enters the Mad River Valley. There are a lot of options for food and beverage in this area, so choose wisely. Lawson’s Finest Liquids is one of Vermont’s premier craft breweries. They also serve food. Then there’s Mad Taco, which is another great choice. Further along on the route in Warren is the Warren Store, which is another excellent place for lunch, serving great sandwiches with a relaxing porch area next to the river. You can also get a pie and beer at American Flatbread. There are multiple B&B options for lodging in the area, as well as Hostel Tevere, a more affordable lodging option with bunk rooms.

location Waitsfield-Blueberry Hill

Day 10 (35 mi +4,300 ft)

Prepare for a big climb as you leave the Mad River Valley. Albeit relatively short, Lincoln Gap is as relentless and steep as it gets. After the climb, a fast descent leads into South Lincoln on gravel, where the route begins to head due south along Breadloaf Mountain. There’s a short brushy section of snowmobile track before crossing 125 near Deacon Hill, then the route heads back into national forest land. Near the Sugar Hill Reservoir, there’s a nice stretch of singletrack that meanders over to Blueberry Hill. You can either veer off and camp at one of several sites near the reservoir or mosey on to Blueberry Hill, where there’s an inn or several campsites available via Hipcamp

location Blueberry Hill-Poultney

Day 11 (46 mi +3,000 ft)

Leaving Blueberry Hill, EDT3 continues on gravel roads and then rougher two-track before descending into the Otter Creek Valley. Otter Creek got its name from the Abanaki word Wnekikwisibo, which roughly translates to “otter river.” The route uses a mix of gravel and paved back roads before mounting the ascent up to Bird Mountain Wildlife Refuge on Birdseye Road. This nice climb eventually turns into Ames Hollow, an old town highway turned lovely Class IV road that drops into Poultney. Be sure to check out Analog Cycles in Poultney, as well as excellent food and beverage at the general store on your way in. And find more logistics info under the Must Know tab.

Terms of Use: As with each bikepacking route guide published on BIKEPACKING.com, should you choose to cycle this route, do so at your own risk. Prior to setting out check current local weather, conditions, and land/road closures. While riding, obey all public and private land use restrictions and rules, carry proper safety and navigational equipment, and of course, follow the #leavenotrace guidelines. The information found herein is simply a planning resource to be used as a point of inspiration in conjunction with your own due-diligence. In spite of the fact that this route, associated GPS track (GPX and maps), and all route guidelines were prepared under diligent research by the specified contributor and/or contributors, the accuracy of such and judgement of the author is not guaranteed. BIKEPACKING.com LLC, its partners, associates, and contributors are in no way liable for personal injury, damage to personal property, or any other such situation that might happen to individual riders cycling or following this route.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.