Baldy Bruised

Originally published in the fifth issue of The Bikepacking Journal, Baldy Bruised is Michael Zhao and Conan Thai’s story of escaping the city for a grueling four-day ride through the mountains beyond Los Angeles, all without relying on cars on either end. Read about their trip here…

When touring off road, progress toward the destination is rarely easy. But there’s a comfort to its inevitability. My body may be screaming out of thirst, hunger, exhaustion, injury, or all of the above, but so long as the cranks keep spinning, I know we’ll reach our goal.

This is easier said than done when riding with stronger cyclists, such as my friend and Silk Road Mountain Race finisher, Conan Thai. Conan’s the type of cyclist whose idea of a short 24-hour overnighter consists of biking from Brooklyn to Vermont and back again in the rain. When I signed up to join him on a four-day, early spring ramble through the mountains surrounding his hometown, the Los Angeles suburb of Garden Grove, I knew I would be exploring the limits of my physical abilities—and I was looking forward to seeing what I would find.

If you look closely at the transit map of almost any city in America, you’ll be surprised by the types and lengths of trips that can be strung together at the margins. For example, Portland, Oregon’s Mt. Hood Express bus service can take you from easily accessible transit hubs to some of the mountain’s most popular ski resorts (and unpaved forest roads) for just $2 each way. Denver’s Regional Transport District commuter rail ends six paved miles away from the foot of the Rocky Mountains. As for LA, its Metrolink commuter rail spans the full 182 miles between the surfing capitals of San Diego and Ventura.

By cross-referencing BIKEPACKING.com’s route map with LA’s transit map, Conan realized that it’s possible to ride across nearly the entire length of the San Gabriel Mountains from Mount Lukens to Big Bear Lake—through land formerly occupied by the Tongva and Serrano tribes—without relying on a car for shuttling purposes. The Baldy Bruiser and LA Observer routes tie nicely into each other, conveniently bound by Metrolink stations at either end. This involves about a dozen or so paved miles between national forest wilderness and the nearest transit hubs, but that’s a small price to pay given the 160 miles of dirt road, singletrack trail, and destination-worthy asphalt miles that await in between them.

At the crack of dawn on the first Monday of March, I reassembled my bike in Conan’s parents’ driveway by the pink light of the rising sun. After dividing up our food for the trip, we said goodbye to Mr. and Mrs. Thai and commenced pedaling through suburban rush hour traffic toward the Santa Ana Regional Transit Center. Soon after, we found ourselves aboard a Metrolink train car alongside our fully loaded bikes docked in the designated bike area. This stood in stark contrast to the perennially crowded Metro North rail system of New York City and its surrounding areas, which doesn’t even allow bikes on board during peak hours, forcing cyclists to appropriate space set aside for people with disabilities.

Our train arrived in downtown LA right on time and we set off under clear blue skies toward the snow-capped hills that formed the horizon. I was expecting a lot of pavement to start the trip, but Conan’s meticulous route scouting put us on an improbable series of dirt connecteurs that roughly traced the banks of the Arroyo Seco (Spanish for dry creek). In fact, we barely touched asphalt between Union Station and the sprawling NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory campus—where the sidewalk ends and the Angeles National Forest begins.

However, like any tale of adventure worth retelling, the punches started early and didn’t let up for the duration of the tour. Before we’d even left the city limits, I managed to yard-sale off the trail. I found myself sprawled upside down against the trunk of a rotting tree. Thankfully, I managed not to break bones or ligaments, but there was a large chunk of spongy, rotting wood sticking out of my left knee. Upon reuniting with my bike, a dozen-odd feet away, I was relieved that my derailleur hanger was the only casualty, though thankfully it was just bent, not broken. After some tinkering, I was able to reliably get into the granny gear and could find most of the others by employing a two-down one-up shifting strategy. My knee was starting to swell from the impact, but I was able to wash most of the wood bits out with a water bottle. I decided to take some ibuprofen and hope for the best.

Later that evening, we nearly lost my brand new tent over the side of a cliff when a gust blew the whole thing off its stakes. Luckily, a bit of sagebrush snared it. Upon recovering our abode, we piled rocks into each corner and finished staking out the rainfly, hoping to find some respite from the ripping winds. Despite having climbed 4,325 feet in just 22.5 miles that day, we lay sleepless as the wind howled all night, whipping bucketfuls of sand under the hapless fly, through the mesh tent walls, and all over our bodies.

We acutely felt the lack of sleep as we broke camp the next morning for what was intended to be the longest mileage goal of the whole tour. A friend who’d recently ridden in the LA Tourist, a 120-mile, all-terrain checkpoint race that overlapped with parts of our route, warned Conan that the Rincon Red Box Trail had “some” downed trees blocking parts of the path. That was before the previous night’s wind storm. The descent into Devil’s Canyon was a pure delight, but the climb up to Newcomb Pass was an impassable morass of freshly fallen tree matter. Dozens of decades-old trees were uprooted by the wind. Trees that fell took others down with them as they rolled to their final resting place atop the relatively flat surface of the access road we were trudging up. The whole area smelled of freshly excavated earth and wet wood and was swarming with biting flies.

This three-mile climb should’ve taken us under an hour, but it ended up taking four. Just as we exited the branches of one tree, we’d be right in the clutches of the next one. Squeezing our bodies through the gaps was difficult enough, but having to drag our bikes through them was far more of a production. If someone were to specifically design an object to get entangled in a fallen tree, it would likely resemble a fully loaded bikepacking rig, complete with dangling zippers, straps, spokes, and pedals. By the time we finally reached the top, my legs looked like they’d been mauled by a family of wolverines. Utterly and completely exhausted, I confessed to Conan that this had been the most physically exhausting thing I’d ever done. In retrospect, I spoke too soon.

After climbing 3,500 feet up the western face of Mount Baldy on the third day, we expected an equal and opposite descent down the other side. Instead, we faced a sock-soaking, toe-freezing slog through four feet of half-melted snow that had the consistency of wet cement. Even after we’d cleared the snow, we had piles of football-sized Coulter pine cones to contend with. It was like trying to roll through a ball pit, only the balls were made of spiky wood instead of soft plastic.

At the top, I sat on a sun-drenched rock overlooking the San Bernardino Valley below while Conan tended to his fourth flat in as many days. As I alternated between taking in the view and watching Conan work, it occurred to me that I hadn’t heard him speak a single negative word during our time together. I recalled seeing a Buddhist shrine in his parents’ living room, so I asked if his religion had anything to do with his equanimous disposition. He informed me that his parents’ shrine was more of a nod to the rituals of their Sino-Vietnamese homeland rather than a reflection of their religious beliefs. After thinking about my question for a few more moments, he added, “I think I’m just stubborn.”

As a strongly opinionated person from a young age, I’ve been accused of stubbornness by many people throughout my life. I’d never thought of it as anything but a smear. Yet here was Conan, owning stubbornness as the source of his strength. The more I thought about it, the more it fits. After all, what is “stubbornness” other than an unwillingness to give up in the face of overwhelming reasons to do so?

When I’m in the saddle, I’m not thinking about the pain of the moment. I’m not thinking about how great it’s going to feel to finish the ride. I’m not thinking. Period. Surrounded by wilderness, fully present in the inadequacy of my physical existence, the anxiety of an entire self and the oppressive weight of a whole society melt away, even if only for a moment. In the interim, all I know is that I have one task: put one foot down after the next, whether I’m on or off the bike. And I know that if I do this, good things will follow.

My list of good things from this ride started with a golden hour descent along a groomed singletrack trail into a shrubland valley, washed pink in the light of the setting sun as the moon rose over the horizon and the city skyline started to twinkle in the distance. It also included the sense of wonder I felt while climbing an empty road beneath a cloudless, starry sky, miles from the nearest source of light pollution. I’d also add the carnal pleasure of consuming a cheeseburger, club sandwich, two orders of fries, and a freshly poured pint after a 16-hour day in the saddle, followed by the sheer decadence of booking a last-minute hotel room with a hot shower and functioning fireplace. Conan would insist on including the unadulterated, childlike joy of playing in freshly groomed snow at the top of the steepest road we’d ever climbed. And I won’t soon forget the rush of adrenaline that came from descending quickly enough to pass cars driving on a paved road.

As I reflected on these highlights before our final descent, I couldn’t fully shake a twinge of disappointment. Despite our best efforts, we were unable to complete the tour as planned in our budgeted time. Between my multiple crashes, the fallen tree gauntlet, barely penetrable snowdrifts, and an optimistic daily mileage goal, we’d fallen short of Big Bear Lake by some 60 miles. But our ability to accept that reality and cope with it was its own victory of sorts. Not being accountable for a parked car, we simply pulled out a smartphone to find our way to the nearest transit center.

Due to our last-minute change of plans, we were treated to one final golden hour dirt road descent instead of having to endure a paved slog down the narrow shoulder of a two-lane highway. I was happy to end on this high note, but the joy didn’t last long. I cased both rims on a sharp rock barely 100 feet from where we’d started rolling. Both tires let forth streams of sticky orange sealant, covering my bike, body, and clothes with quick-drying latex. I was eventually able to plug both tires before they fully flatted, but it was a rough ending to an already grueling tour.

After the dirt ended, we rolled down a few paved miles to the nearest In-N-Out Burger in San Bernardino, where we shared one last meal. As always, I ordered two cheeseburgers, one “protein style” because I tell myself that replacing the buns with lettuce constitutes a salad. After finishing our food, Conan opted for the next bus back to his parents’ house in Garden Grove because the next Metrolink train was still an hour away. This was easy to do since every city bus in the region comes with a folding bike rack on the front. Meanwhile, I pedaled a few more miles to spend a couple of nights at a friend’s place in Loma Linda.

As I cruised past eerily similar strip mall after strip mall, I thought about how easy it was to ride on these wide, flat, paved roads. Despite a significant headwind, it felt like riding an e-bike compared to the chunky gravel surfaces we’d been battling just hours earlier. In spite of my surroundings, I was still genuinely enjoying myself.

My whole adult life, I’d been telling myself that I needed a car to access the outdoors. And yet, in 10 years of car ownership, I’d never attempted, let alone completed, any trip nearly as ambitious as the one I’d just done without any driving at either end. Maybe a car isn’t such a necessity after all.

As much as I would like to end this story with me selling my car, the truth is, I’m not there yet. The car is simply too convenient. But I’ve seen the destination and the route to get there. Perhaps it’s just a matter of time.

About Michael Zhao

Michael Zhao is an adventure cyclist residing in Brooklyn who seeks busted gravel roads and root-covered trails all over New York and New England. He was a lifelong bike commuter and home mechanic before catching the bikepacking bug in 2018. He enjoys building bikes at least as much as riding them. You can keep up with his latest rides and builds on Instagram at @mhzhao.

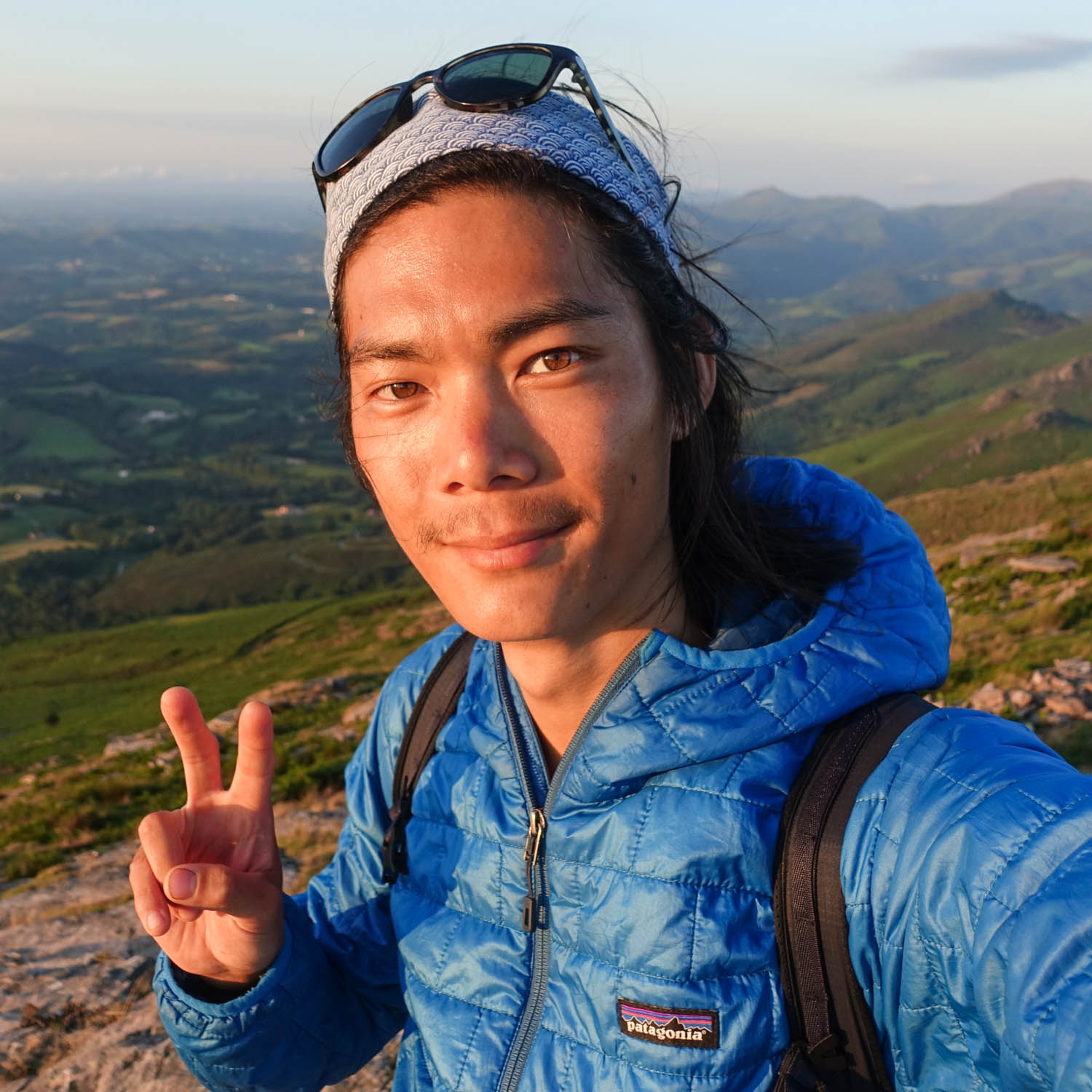

About Conan Thai

Conan Thai is a Chinese-American photographer based in Brooklyn, NY. He graduated from the University of California, Irvine with a BFA in studio arts. Growing up with working class roots, he lived in books, played with matches, and dug holes in the backyard garden. He’s fascinated with environmental sustainability, decay, life from entropy, the death drive, film theory, narrative structures, and situationistic ‘aha’ moments when the senses clear and the fog lifts. Find him on Instagram @everydaycult_.