Four hours into a grueling bushwhack, I realized our little weekend adventure wasn’t shaping up anything like I’d imagined it would be. It’s not as if we didn’t have time to learn more about our route before setting out; my friend Justin and I had been scheming this trip for well over a year. However, for one reason or another, actually forming the plan was a last-minute affair, and before we could gather any real beta on what we were getting ourselves into, we were bouncing down a gravel road on vintage mountain bikes loaded with BB guns and packrafting gear.

For most of us, getting older comes hand in hand with having more responsibility, an achy back, and a busy schedule that makes it harder to escape the mundane. Squeezing in an overnighter or weekend-long bikepacking trip close to home is sometimes as good as it gets, and given the constraints of a busy life, a little creativity is often required to keep things interesting.

I’m fortunate to have a small group of like-minded friends who are equally excited about spontaneous get-togethers and pushing bikes up steep hills. These particular friends are no strangers to type II fun. In fact, I’d say we all feel a certain attraction to unorthodox pedal-powered trips. Whether they involve freezing cold, pouring rain, or, in the case of Klunk ’n’ Float, a questionable assortment of bikes and gear, we’ll do anything for a good time and a story. Our younger selves wouldn’t shy away from uncomfortable situations or turn down an adventure. So it seems only fair that, even though we now have deadlines and responsibilities and aging bodies, we should still do our best to seek out adventure, however big or small or close to home.

DAVE AND THE KUWAHARA

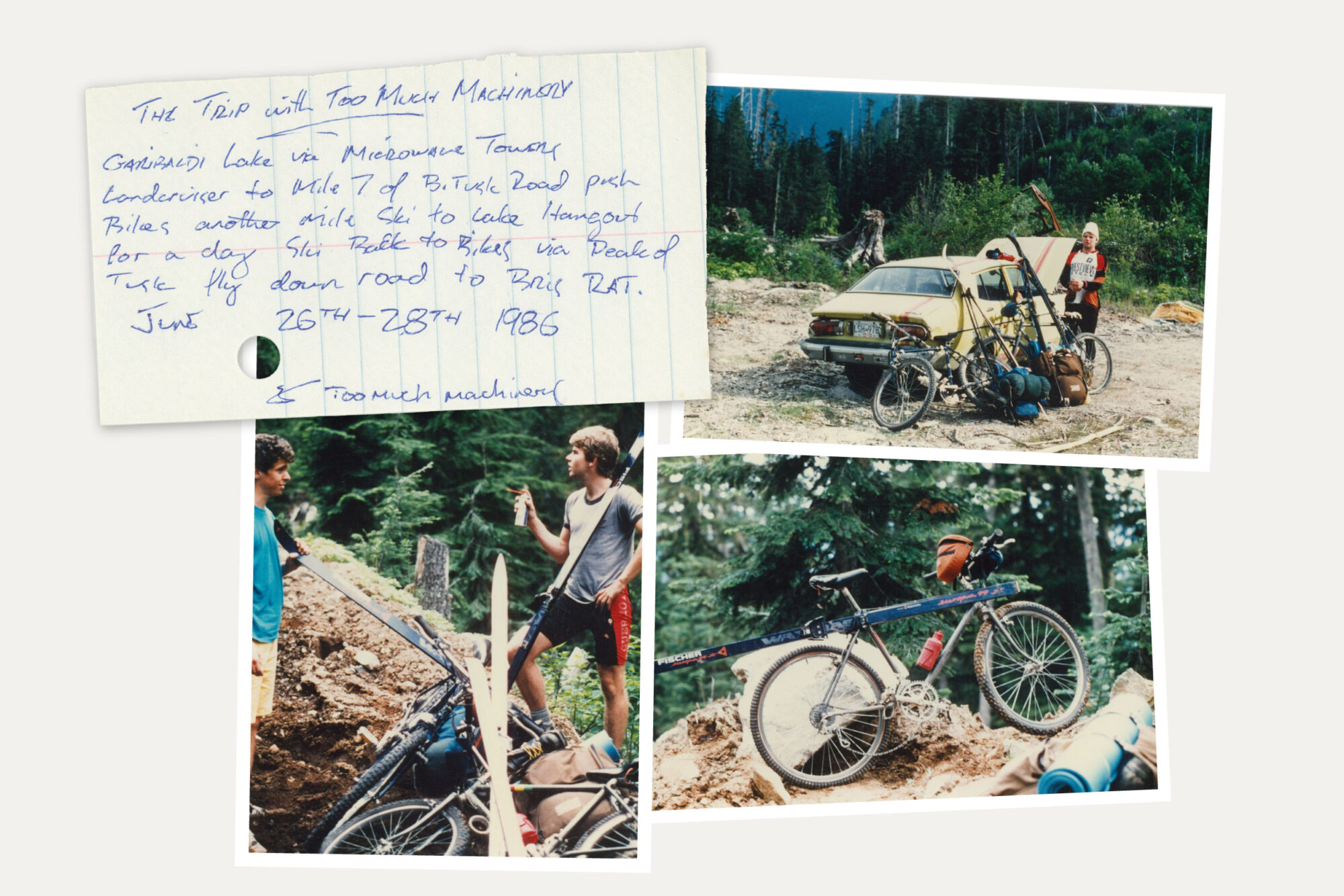

One nice thing about living in a small town is that word of the trip we were planning spread quickly, naturally reaching folks who share a similar appreciation for this style of ride. Among those was our friend Dave Opko, a strong cyclist and longtime local who knows the area’s maze-like patchwork of gravel roads better than anyone. Not long after the trip, he recognized the Kuwahara Cascade I was riding, asking if I bought it locally, as he’d bought an identical one as his first real mountain bike in the early 1980s. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, Dave set out on some “epic OG multi-sport trips,” as he put it, often involving heavy canvas backpacks, telemark skis, and the Kuwahara.

During his time living in Whistler, Dave and his friends would drive their parents’ cars as far as possible down gravel logging roads and then transition over to mountain bikes, which at that time were brand new in North America. There were no purpose-built mountain bike trails like we know today. Mountain biking was simply riding gravel roads outside of town, and for Dave’s group of friends, they were a way to access more snow.

He described creating a front rack out of skis to support his heavy pack and how they would transition to pedaling in their bulky, leather, three-pin telemark boots when things turned muddy. Dave insisted that they rarely loaded up bikes with gear just for the sake of camping; it was almost always based around some sort of activity. Their parents never knew where they were headed, and they’d often run out of food on multi-day trips.

One time, when rodents ate the sidewalls of his tires, Dave simply pedaled the 30 kilometers to town on the bare rim. This mentality has followed Dave into his 50s. He remains inspired to keep riding by those early trips and the bike-accessible loops that haven’t been connected yet. He continues to seek out new terrain by bicycle and usually plans a big trip or two from his front door each year. He’s still obsessing over topo maps but is assisted by satellite imagery and GPS devices these days.

When talking to Dave, what stuck with me was his suggestion that the trips of our youth, before published routes and bikepacking bags, were merely a product of what was available at the time. Back then, that Kuwahara Cascade was a top-of-the-line mountain bike, and poring over paper maps was the only way to plan trips into the backcountry. Compared to today’s detailed route guides and the internet-powered connectivity of social media, there were a lot more unknowns. Something as simple as checking the long-term weather forecast has become almost second nature these days, setting us up for success or, in some cases, disappointment.

EAT, SLEEP, KLUNK

There’s something refreshingly childish about loosely planned trips. And the fact that Klunk ’n’ Float was in our own backyard allowed us to hold it even more loosely than usual, purposefully leaving much of the logistical planning at arm’s length and not feeling the need to understand or control every last moving part. A youthful optimism and energy surrounded the entire trip.

We didn’t really have an idea of what we were getting into, and to make things even more interesting, Justin insisted that we ride vintage mountain bikes. I’m talking fully rigid, 26-inch wheels, rim brakes, tubes, and heavy steel frames. The type of bikes that are perfect for smashing through thick ferns and tangled blackberry bushes like medieval battering rams. Mounting up on our bikes, it was hard not to think back to the adventurous days of my youth spent wielding deadly sticks and fighting imaginary beasts from Middle-earth in the forest behind my house.

Growing up, my brothers and I would spend hours outside. There was never a plan, we didn’t follow prescribed routes, and we were joyfully underequipped most of the time, making do with what we had. We slept outside in budget sleeping bags under makeshift shelters, stomped through mud and rivers, and toppled dead trees without even considering the consequences of a blunt impact to the skull with no adults in sight. We were free. To me, it feels only natural to crave that feeling again every now and then. Well, except for the blunt impact part.

Our Klunk ’n’ Float bike setups were a hilarious mix of old and new. Our retro mountain bikes were laden with fancy inflatable rafts made from modern TPU and Kevlar, and the two tents we packed for the group cost well more than all of the bikes combined. Unfortunately, even the lightest camping gear and minimal packing lists had little effect on the weight of our burly rigs.

Justin ended up on a salvaged, fluorescent 1990 Nishiki Barbarian, complete with trend-setting elevated chainstays, a blue-green fade paint job only a mother could love, and a custom BB gun holster constructed from the top tube of a decommissioned Norco Range. I acquired a bombproof 1980s Kuwahara Cascade locally for $100, outfitted with ATB-approved bullmoose bars, chunky tires, and a BB gun mounted on my handlebar roll for easy access. Kristjan arrived from Vancouver Island with a box full of donuts and rode a borrowed, too-small Miyata with swoopy handlebars. Nathan borrowed a deep purple Specialized Stumpjumper with ergo grips to support his wrapped-up hand that had undergone surgery just a week before. We all laughed nervously at the absurdity of our bike choices, aware that the outdated gearing wasn’t designed with pedaling 70-pound rigs up double-digit grades in mind.

Although we knew the route would be mostly passable, a few major question marks remained. We were prepared for the rough doubletrack and slow water crossings with our packrafts, but we knew it was only a matter of time before our trusty steel rigs would let us down. We pedaled steadily and without incident for hours, testing the limits of our bikes on the descents and our willpower on the climbs. Metal scraped metal as we desperately tried to persuade our front derailleurs to push our chains down onto our smallest rings, which in hindsight were the only ones we ever needed. Still, coaxing derailleurs, eating candy, and deciding whether to push or ride are struggles I consider far less stressful to navigate than my daily routine at home. I’d take a grueling hike-a-bike over sitting hunched in front of my laptop any day.

The wonderful thing about a multi-sport trip involving packrafting is that the transition from land to lake and back provided natural breaks in our day. We filled those moments with target practice and gummy bears, passing around a multi-tool to check the various bolts holding our bikes together. We were unanimous in our decision that the only rule of Klunk ’n’ Float was that bolts had to be tightened regularly, a ritual we religiously adhered to during our time together.

Between the four of us, we carried far too many 26-inch tubes, a number of patch kits, a full-sized socket wrench, a family-sized package of Double Stuf Oreos, and enough mac and cheese to feed an entire high school sports team. We somehow snuck by without any major mechanicals, aside from a single flat tire, which was impressive considering how little preparation or pre-trip maintenance any of our bikes received. Almost miraculously, they just worked.

The crux of the trip was a short section of old hiking trail down a steep descent that connected two lakes. We’d received unclear beta from locals on how passable it would be, hearing everything from, “It was great 20 years ago!” to “Bring ropes!” to “It’ll be totally okay if you’re stubborn.” Unfortunately for us, it was worse than we could have imagined. The “trail” was non-existent, forcing us to push and pull our bikes through heinously thick brush, across creek beds, under fallen trees, and through forgotten logging land. Overgrowth made our arms and legs bleed, wasps stung us, and at times, we simply had to hurl our heavily laden bikes over small ledges to help clear the way. At one point during the bushwack, I suggested that lighter setups might actually be harder to pull through this mess and that our lugged steel frames and packrafting gear might even be working in our favor. This idea was mostly met with groans from the group. We’ll never find out, however, as we all agreed never to replicate that hike-a-bike again.

Our one-kilometer hike ended up taking us more than four hours and was a good taste of type II fun. The hike-a-bike sent us to a dark place, fueled by uncomfortable conditions and our snail-like pace, making the finish that much sweeter. I scoffed at Justin when he carried his entire setup on his shoulders while I struggled in the creek below. I enviously watched Nathan as he picked his way across massive logs, like a carefree wood elf, as Kristjan and I crawled through the brush on our hands and knees. All of us had different opinions on the best way to bushwhack, if left or right around the tree was faster, and whether we should follow the creek or stick to the treeline. Tensions were rising, but thankfully the cool waters that greeted us at the finish line cooled off our bodies and minds.

Now, back at home with the inaugural Klunk ’n’ Float beginning to feel more like a distant memory, it’s easy to look back at it fondly. Although we chose vintage mountain bikes, packrafts, and BB guns with hopes of recapturing the spirit of our youth, they didn’t play as big of a role as we’d first imagined. In the end, it was simply packing in one last summer weekend outside with friends that reconnected us with that feeling of youthful exuberance. Our days were full of camaraderie, laughter, and constant reminders that taking time to enjoy a skinny dip, snack break, or impromptu target practice is what these trips are really all about.