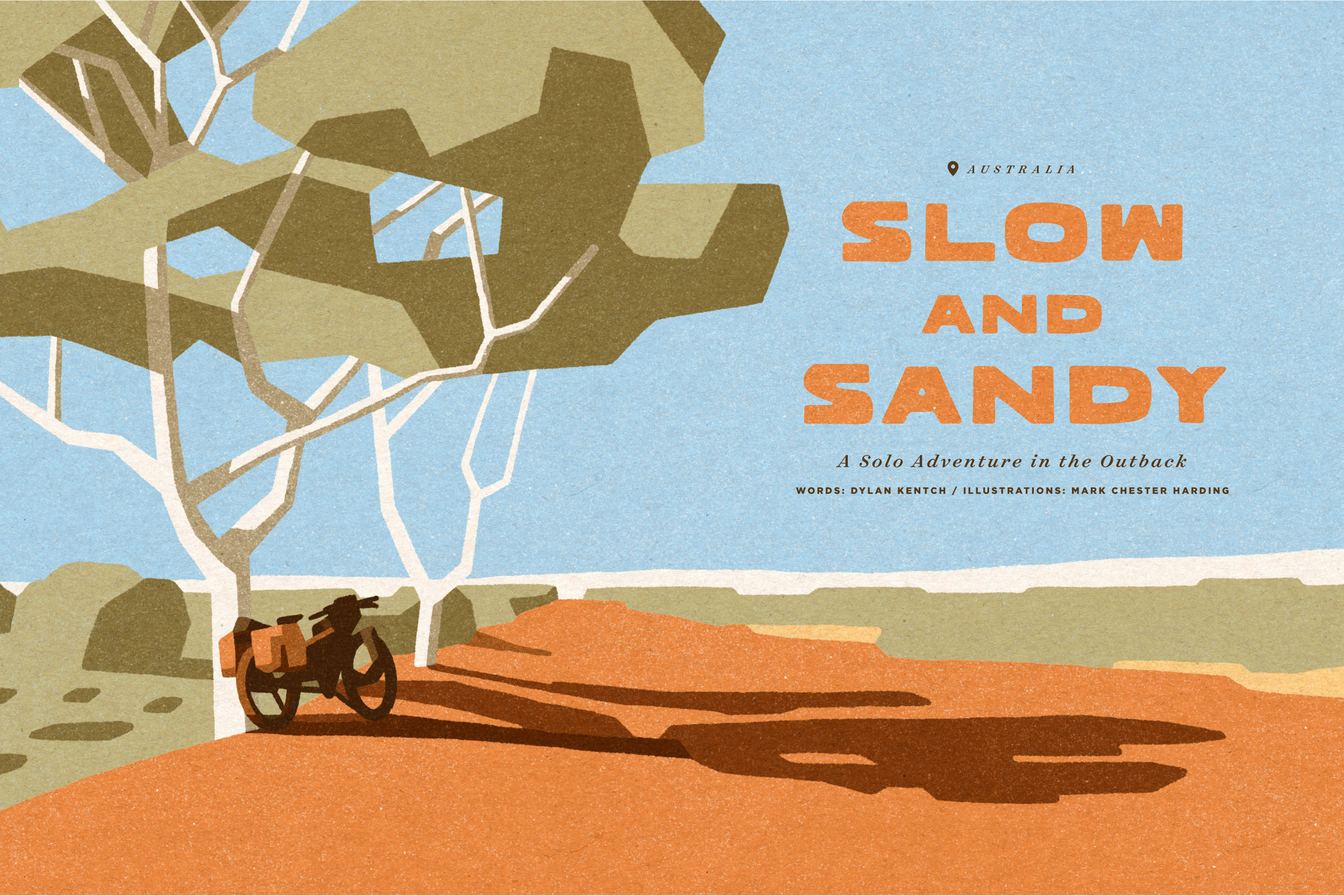

Slow and Sandy

Following a two-week solo bikepacking tour along the Australian Outback’s Anne Beadell Highway, Dylan Kentch put together this reflection that weaves together the past and present. Read about his experiences of pedaling at a snail’s pace through a 1,300-kilometer stretch of remote, arid, and unforgiving terrain here…

I cycled from Laverton to Coober Pedy on the Anne Beadell Highway, the rough and sandy road connecting the states of Western Australia and South Australia. It was slightly longer than 1,300 kilometres, and I went alone. It would have been a fun ride with someone, and indeed if anyone had asked, I could have provided a loaner titanium fatbike, and we could have taken my two-person tent. But no one did. And so, when I didn’t avail myself of the only possible shower during the whole ride, there was no one around to ask why. Perhaps it was easier this way.

Two weeks of desert touring with no shower is fine. Comfortable with my own particularities, I screamed with glee to no one while coasting down sand dunes. I smelled the wet stuff on my fingers twice to ascertain if my tyre was losing sealant or if I’d run over a particularly juicy camel poo. It was indeed the latter. And I had only myself to ask about the wisdom of purposely not bringing a stove, raincoat, or chamois on a two-week trip into the Outback.

It was a fucking sweet trip. Sick. Filth. I could continue writing the superlative adjectives I hear young mountain bikers utter at my retail job in a bicycle shop, but I don’t have to do this to drive home the point that this was a sublime and serene bike tour. It was one that went to expected and unanticipated extremes. In the end, it was more than everything I desired.

Len Beadell was a surveyor, cartographer, and road builder who worked for the Australian federal government from the 1940s to the 1970s. He and his work crew, known first casually and later officially as the Gunbarrel Road Construction Party, built the majority of the dirt roads in northwestern South Australia and eastern Western Australia. Beadell named many of the roads he built after his family members; Anne was his wife. His children Jackie, Connie Sue, and Gary all have their names written across on those big fold-out Hema desert maps too.

Initially, Beadell’s roads helped the British government explode nine atomic bombs in South Australia in the 1950s and, later, the Australian Department of Defense launch its Woomera rocket program. The roads provided access to bomb test sites and helped to track missile trajectories and mushroom cloud fallout patterns. In total, it conducted 12 bomb tests from 1952 to 1957—these nine and an additional three at the Montebello Islands. I used to live on the Gunbarrel Highway in South Australia, and I met people whose elders had seen the mushroom clouds. The history behind these tests isn’t pretty, so I didn’t cycle out to Totem One and Totem Two at Emu to see these sad and scary monuments.

This road system, many years later, makes the Great Victoria Desert more accessible to cyclists like me. Starting just outside of Laverton, the Anne Beadell Highway goes almost due east to intersect the Stuart Highway a few kilometres north of Coober Pedy. A few cyclists had ridden across it in its entirety before me, but not many. To the best of my research, Scott Felter of Porcelain Rocket was the first person to do so entirely self-supported. That was in 2018. I took comfort in knowing that it was indeed possible, as someone else had been there on a bike before me.

The road is 100 percent unpaved, sometimes extremely corrugated, and often quite soft and sandy. South Australia hasn’t graded the road since the 1960s, and the Western Australia side gets bladed maybe once or twice a year—and that’s the pre-COVID frequency. To quote Wikipedia, “Beadell’s sense of humour was well known, and he referred to many of his roads as ‘highways.’ The description stuck, and maps show the subject roads as highways, despite the reality that they have degraded to single lane unsealed tracks through the remote arid areas of central Australia.”

I had 80-millimetre rims and 26 x 4.8-inch tyres and never once regretted this selection. Stronger riders have ridden this road with 29 x 3-inch tyres on 30-millimetre rims, and I’m flabbergasted and amazed by this. I would probably still be walking out there if I’d taken my 29-plus bike. But over the full route, I pushed up four sand dunes for a cumulative total of less than one kilometre on foot. I ran a friction thumb shifter from a flat-bar road bike connected to an XT front derailleur and a 2×10 drivetrain. I limited out the smallest three cogs so the rear rack bolt would fit and never used the largest 42-tooth cog in the rear since I never use the lowest gear on any bike. Perhaps it was more aptly a 2×6 drivetrain. I had no mechanicals other than a consistently lazy rear derailleur. If the combination of more than one chain, an indexed thumb shifter, a long-cage XT rear derailleur, and four-year-old shift cables culminates in lazy shifts, I’m alright with that. Maybe my crankset went a little bit loose too.

I have some heavy thoughts that are still working themselves out. Perhaps, I hope, I can one day distill the calm and serenity I experienced in the remote desert into something more than a bunch of scattered clauses and phrases. I’ve never been somewhere so quiet before. No permanent water sources near the road meant there was no stock nearby, and how lovely it is to cycle in Australia and see neither sheep nor cattle! There were also no crickets or mosquitoes and no crows yelling in the mornings.

When the winds dropped away at night, even the desert oaks stopped their mystical whirring, and all was quieter than quiet. Sometimes, in the morning, freshly on the bike, I couldn’t immediately identify the horrendous thumping noise that beat rhythmically around my head. As always, the culprit was the zipper on my windbreaker flopping around. I have tinnitus in one ear, which is also very hard of hearing, and I always have a relentless high-pitched whining in that ear. What I heard and didn’t hear from nature on this trip overwhelmed all of my previously known audible experiences.

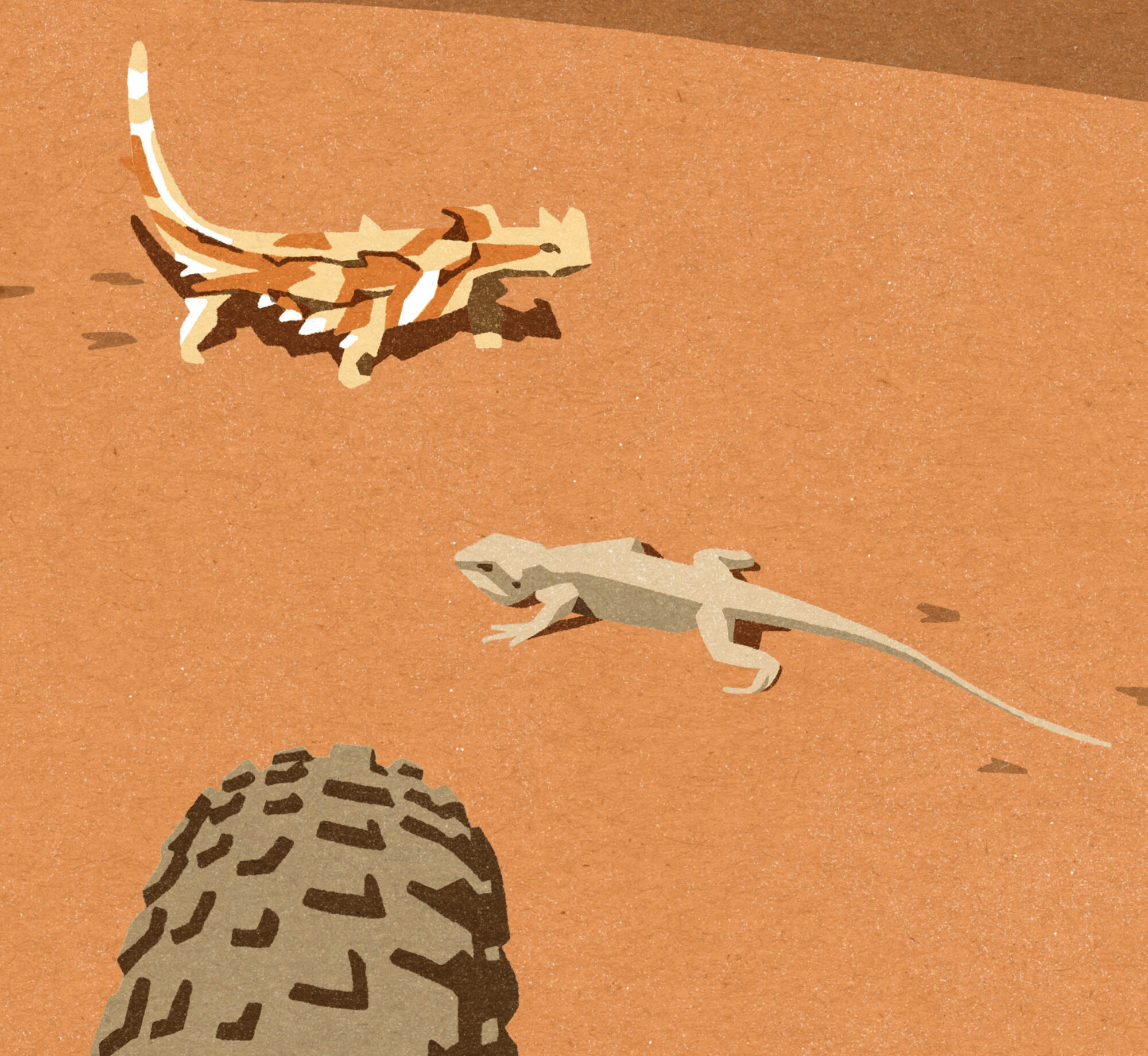

This trip was a numbers game, and figures controlled much of what I did every day. I had insomnia for the first half of the trip, and for seven nights straight, I was wide awake for three hours before the sun rose. I lay by my fire on the cold sand, wishing I could doze off away from the flames in my (highly flammable) sleeping bag. It was below 0°C every night except for two. I left Laverton with 14.5 days of food, and at some points, I carried more than 30 litres of water. For three days, I saw no vehicles. I saw two thorny devils and three kangaroos: two on the first day and one on the penultimate day. The third was massive, one of the largest roos I’ve ever seen, and was all white.

The dog fence is electrified where you have to take the six-kilometre return to go through the gate, and it will tingle you from fingertips to armpit if leaned on. Ask me how I know. I arrived in Coober Pedy with two tortillas, chewing gum, and 2.5 litres of water, and I can tell you exactly which days those rations came from. At Ilkurla Roadhouse, I ate two tins of baked beans, one tin of peaches, one tin of rice cream, and two tins of spaghetti in a single breath. My bicycle weighed 22 kilograms with sealant and frame bags when I packed it for the flight out to Perth.

I took just over 2,000 photos, and every 4×4 driver I asked to take a picture of me was baffled when handed a camera that was not in the shape of an iPhone 11. I was fined $0 and lost no points on my driver’s license for not wearing a bicycle helmet when stopped by the police before I’d even reached the pizza place in Coober Pedy. I wouldn’t change a thing if I were to ride out that way again. It’s good to do hard stuff sometimes. It’s been years and years since I had a bike tour as life-altering as this one, and I would absolutely go on this trip again.

Lastly, it’s important to know that this bike tour passed through the lands of the Nyanganyatjara, Tjalkanti, Ngalea, Kokatha, and Arabana people. I acknowledge them as the Traditional Owners and Custodians of these lands and recognise that sovereignty was never ceded. I pay respect to their Elders of all generations, past, present, and future, and acknowledge unbroken connections to land, spirit, and community. I was privileged to be able to ride my bicycle here.