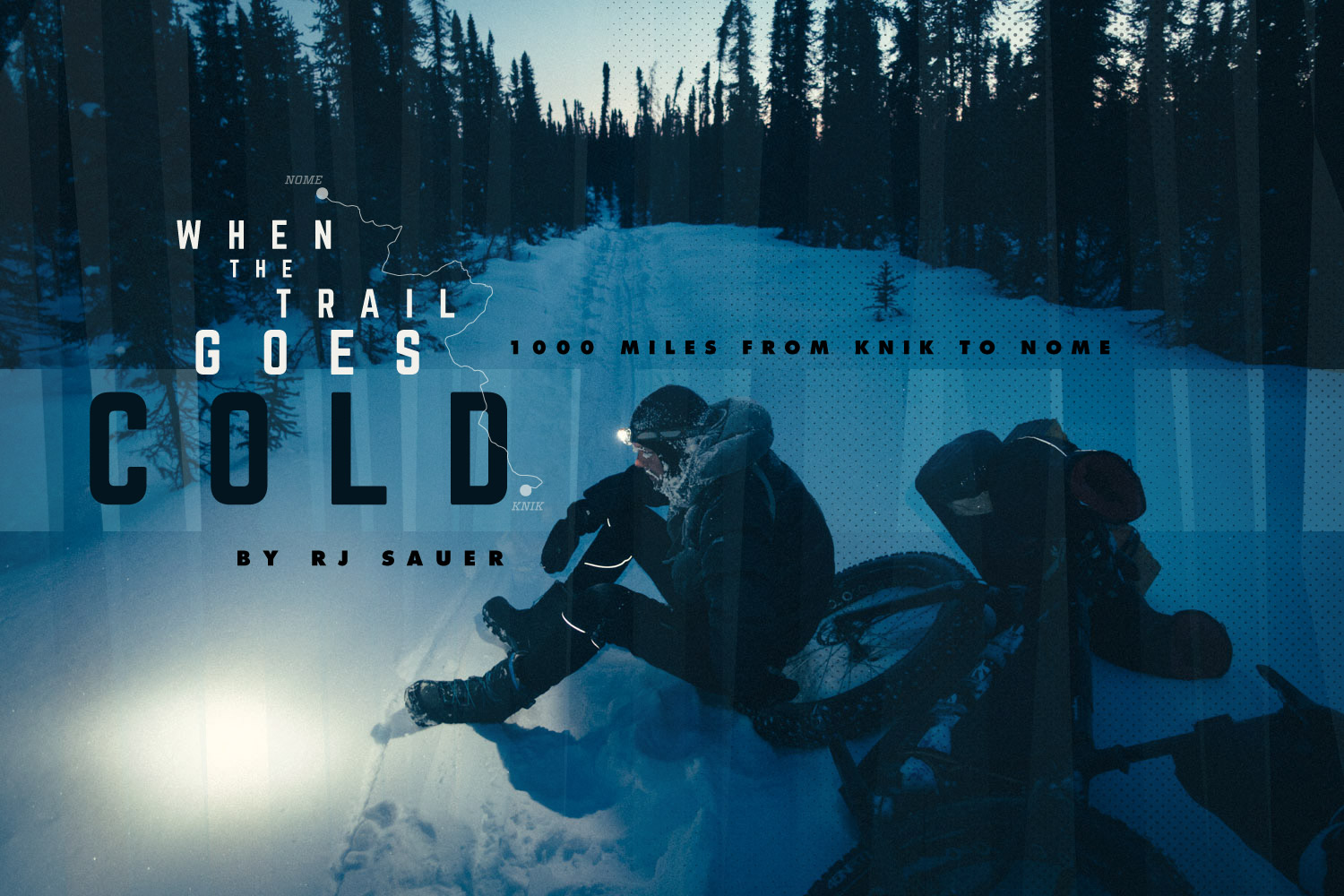

Nothing says Hello Alaska like my cold hands lathering diaper cream over my private parts in the darkness of a winter morning along the Iditarod Trail.

The warmth from the snuffed fire is almost entirely sapped from within the walls of the shelter cabin as I crawl out of my sleeping bag and pack my bike for another day on the trail. Every surface of the outside world and the gear tethered to my Salsa Mukluk fat bike is encrusted in frost. It was another severely cold night, that frigid and dangerous place beyond where Celsius and Fahrenheit collide.

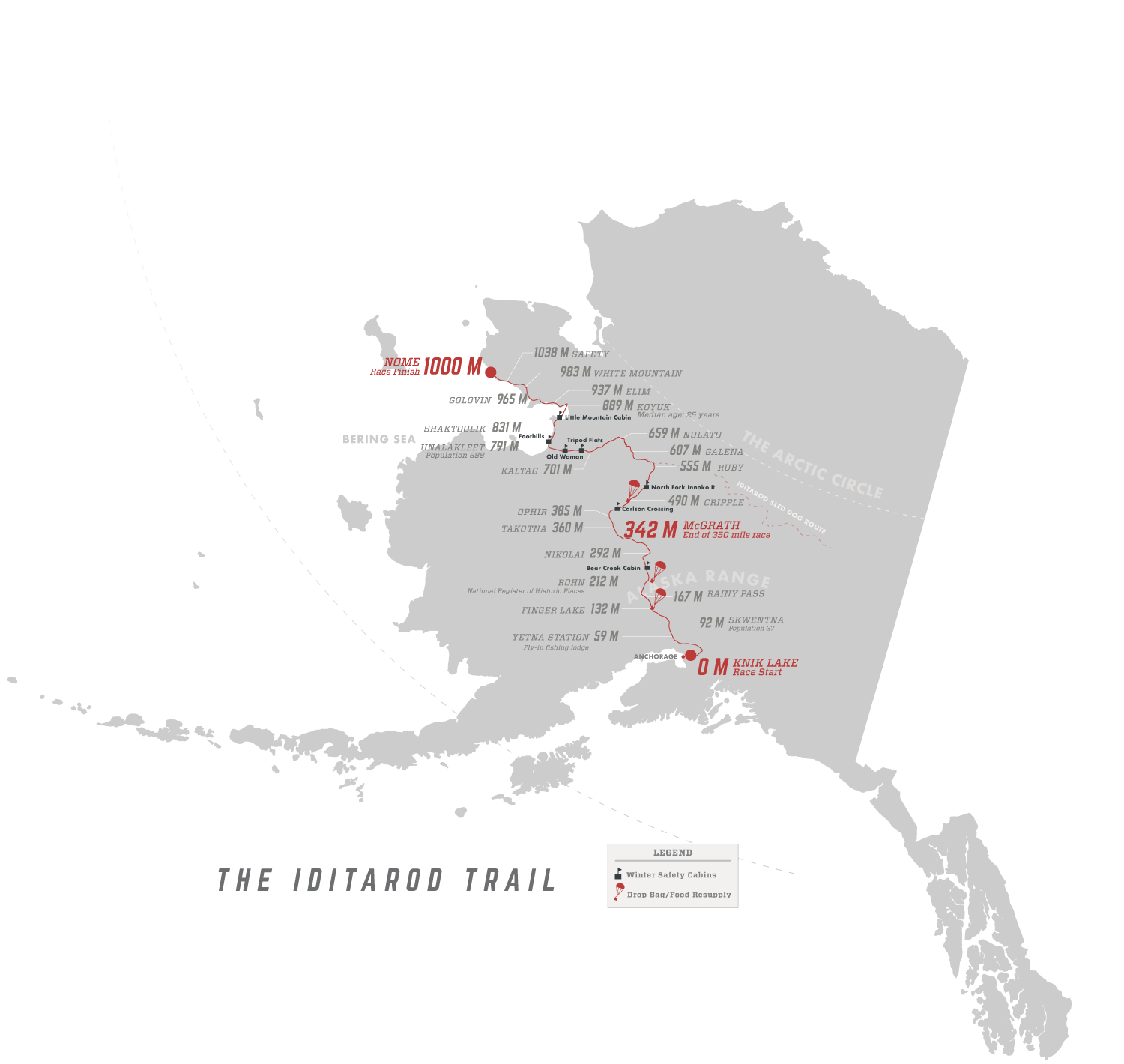

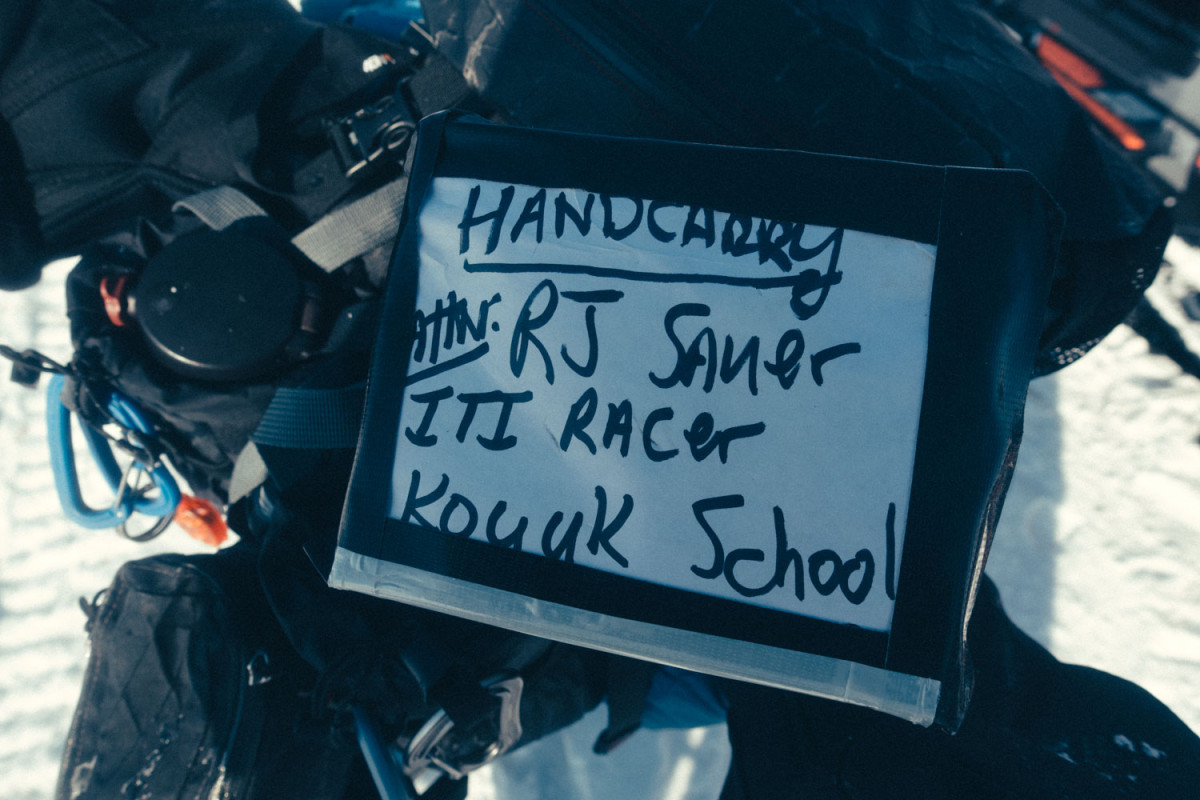

This was my second time competing in The Iditarod Trail Invitational (ITI) on bike, a one thousand mile race along the northern route of the historical Iditarod Trail. With the Iditarod Sled Dog race committed to an official restart in Fairbanks, our race paths would not cross until the Yukon River and the village of Ruby, half way through the race. This meant some anxiety about trail conditions through the more remote sections of the course where we depend on Iditarod trail breakers to carve out some semblance of a trail, specifically through the unvisited and unpopulated areas between Ophir and Ruby. There was also a new section of the race before Rohn, bypassing the traditional Rainy Pass and Dalzell Gorge for the longer passage through Hell’s Gate and Ptarmigan Pass used by the Iron Dog snow-machine race several weeks earlier than the ITI.

Would we have a trail? Only time and Mother Nature would tell.

We enjoyed a relatively balmy departure from Knik Lake, the official start of the Iditarod Trail, near the town of Wasilla, Alaska. My friend Frank Janssens and I casually rolled out with the 80 some odd competitors, unaffected by the adrenaline of those racing the shorter distances and finish lines to Finger Lake (130 miles) and McGrath (350 miles). We remained focused on managing our pace and goal to reach Nome and the 1000 mile finish line. This was Frank’s third attempt, after his disappointing scratches in 2014 and 2015. I was excited at the prospect of standing under the iconic, Iditarod Burled Arch with him in Nome and sharing the realization of his dream once and for all. Not to mention my own second completion of the trail.

The earliest stages progressed with minimal mishaps, although Frank was still fighting off a pre-race chest infection. I settled into my saddle, spinning behind him while trying to avoid his contagion. I had to remain focused, regularly dodging the friendly-fire of his snot rockets, a constant barrage of nasal vapour bursts launched in the air in front of me, instantly freezing into chemical clouds and drifting past like anti-aircraft flak.

We pressed on over mixed trail conditions, moving conservatively from one checkpoint to the next. With every mile the temperatures plummeted and the cold would soon become a major factor in the race.

Puntilla Lake

Day 3 / Mile 170 / -30°C (-22°F)

I dig through the pile of mislabelled tin cans soaking in a pot of warm water atop the wood-burning stove. I hoped for chicken noodle and ended up with a creamy chowder. It would have to do.

An anxiety infested the cabin at the checkpoint of Puntilla Lake, the final refuge before the long path through Hell’s Gate and Ptarmigan Pass. Fellow racers had left in waves, only to retreat from the front lines beaten and shattered by a relentless siege of frigid temperatures, screaming winds and a snow-drifted trail lost in the landscape. Behind us, rumours were surfacing of racers already scratching from sickness, cold and frustration.

Frank and I took the time to rest. His chest infection wasn’t improving, in fact, it was clearly deteriorating and he knew it. But we could still afford to be patient as our goal was reaching Nome. There was no need to be reckless, no use winning the fight only to lose the battle.

We were followed by a small group of groggy riders all tentatively pushing out the door in the early morning darkness in the hope of leveraging daylight hours to get as far down the trail as we could. The initial few miles was rideable and there was no wind to be heard or seen. Maybe our patience had paid off. The truth was the carnage was waiting to ambush us.

We crested a ridge and were hit by a screaming crossfire of winds. We were quickly pushing our bikes, wandering blindly in search of the trail as my goggles frosted inside and out, my clothing encrusted in ice. The cold was suffocating. The weather immediately aggravated Frank’s condition and he was forced to use a prescribed inhaler to facilitate his breathing. He considered turning back but we had already scraped out several hours of progress. I encouraged him to push on to Rohn.

Time and patience paid off. If nothing else, I could always count on time. Change was inevitable. Despite the frigid temperatures, the winds scurried off and we could come up for air. The trail improved and soon enough we could ride. More importantly we could finally open our eyes and appreciate the vast, majestic landscape that surrounded us. Smooth, sculpted white peaks glistening against a crisp, blue sky. The Iditarod Trail has a way of rewarding you for your persistence, or perhaps, luring you deeper and deeper into its grasp.

Once in the canyon and on the frozen river leading into Ptarmigan Pass, the fierce winds picked up again. We found a protected pocket on the side of the shore and tucked beneath the trees, just beyond the clutches of the wind. We gathered loose branches and wood and started a fire which attracted other weary racers and soon we had an impromptu campout.

That night the temperatures dropped to -40 Celcius (-40°F) as we all huddled in what was starting to feel more and more like down body bags. Bivvied out beside the diminishing fire I stared up through the tiny window of my sleeping bag and watched the shimmering dance of the northern lights playing Pong with the starry sky. With every small shift of my body weight a delicate cascade of ice particles, crystallized on the rim of my sleeping bag, showered down onto my face like pixy dust. The surrounding trees creaked, swaying and arching in the gusting winds. Wolves snapped and barked from the darkness, perhaps jealous or territorial, annoyed with our unexpected presence.

In that moment, any superficial misery was overcome by a sense of pure magic. Isn’t this why I came here?

In race terms, we all overslept. Entombed in our nomadic beds, we were slowed by the morning, Houdini-level ritual of dressing inside a down cocoon, organizing and digging out gear and clothing stuffed throughout our sleeping bags felt overwhelming. The cold temperatures had a way of aggravating and complicating the simplest of tasks.

By morning, the night’s cold had sapped the air from my tubeless tires and fused my brake pads. I wasn’t overly concerned by my braking power in this moment but the deflated tires were not ideal. I tried to use my pump but it wouldn’t work. It simply couldn’t generate air. I was delicate with every piece of equipment, especially vulnerable items like my tire valve. Everything seemed brittle from the constant exposure to the cold.

I inefficiently slogged along the ice on the soft tires, anxiously waiting for the pump, tucked under my armpit, to warm up. After multiple attempts I was finally able to get air in my tires, my speed immediately ramped up and I was racing along the trail through the snaking valley of Ptarmigan Pass. I overtook multiple riders, all struggling with the cold in different capacities. It was taking an emotional, psychological and technical toll on racers and their gear. I passed Polish rider Bartosz Skowronski who seemed confused and delirious but was moving slowly forward towards Rohn. To be honest, he seemed no worse for wear, I couldn’t really understand him now but I could never understand him before. He told others he wanted to stop to rebuild his rim so he could ride better.

I was making good time, moving at over 10 miles an hour. My air pressure was perfect and the trail solid enough to stay consistent. I fought the temptation of glancing at my Garmin handheld GPS for my position in fear of the disappointment it might bring to my perceived progress. But I needed to confirm if I had actually made the turn out of the canyon, I craved a sense of where I was and when I finally pulled up the map I was surprised to find I was already halfway to the checkpoint of Rohn. The revelation invigorated and emboldened me. I put my head down and stepped up my pace as if this fast trail might suddenly be pulled out from under me. In fact, for some, it literally did just that.

Rohn

Day 5 / Mile 265 / -38°C (-37°F)

I rode into the temporary camp of Rohn and before long it transformed into an arctic M.A.S.H. unit, a triage tent full of frostbite, injury and fear. In the calm before the chaos I was immediately offered hot Tang and a double serving of giant Bratwurst, the signature dish on offer. The Rohn team was a well-oiled machine, already versed in ITI childcare. We were each politely and calmly encouraged to sit down on the bed of pine branches to dry off and warm up in our sleeping bag as they addressed our needs one-by-one in a sympathetic tone.

The first-in and first-out mantra of the camp quickly came to haunt me and soon I was banished outside at the most awkward of times to make room for the new arrivals as they hobbled in off the trail, many scratching from the race. Several riders had broken through the river ice and had been soaked up to the waist. Others had varying degrees of frostbite on their feet, fingers and face. Bartoz arrived much later and he was one of the worst. He had decided to bivy out on the river after we passed him which exasperated his situation. We weren’t sure if he’d be keeping all of his bloody, frostbitten nose. His fingers were blistered and swollen and like many others would see his race end here.

Frank arrived soon after me and we slept outside the Rohn canvas tent, mockingly within earshot of those huddled inside. His chest infection was bad. He couldn’t hide the doom and disappointment on his face.

Frank made the official decision to scratch in the morning after another cold night bivy. I sympathized as best I could in the moment but quickly recognized I needed to leave. I had already lingered here way too long and the stench of indecision emanating from the other racers wafted on the air. The scratched racers continued to pile up here in Rohn and further back along the trail and with them the sense of mortality, visible proof that a premature end was possible. I prepped my bike and grabbed what food I needed from my drop before hitching to the train of Martijn Boonman and Jeff Bradner, both leaving for the next destination of Nicolai, 75 miles up the trail.

We made great progress through the Farewell Burn. This year’s snow meant a solid, flowing trail and most importantly, no bone-shattering, grass tussocks. Five hours later, we reached JP’s Hunting Camp, or as I called it, the coffee shop. JP’s family had a long tradition on the Iditarod Trail and his family had run the old, now abandoned Buffalo Camp for decades. In a nostalgic gesture and an opportunity for him to fish and hunt the area, JP had reached out to the racers and graciously offered a respite from our race at his seasonal camp. Whether needed or not, this was one of those experiential moments impossible to deny. I had casually met JP in 2001 at the old Buffalo Camp on the Iditarod Trail when he was just a boy. And as fate would have it I rode into his camp that day with another 2001 alum Jeff Bradner. This place had a way of shaping and aligning the stars.

We were greeted with the carcasses of critters strung from the trees like Christmas ornaments.

We ducked inside the sauna that was their small canvas home and accepted the very civilized offering of peanut butter and jam sandwiches and thick cowboy coffee brewing on the wood stove. Disco hits sputtered from an old radio. The decadent sojourn might as well have been high tea at the Shangri-La as we basked in the warmth of the sincere and unselfish hospitality of our hosts.

Weaving through the frozen rivers and trees out of Nicolai, I was followed by a large and curious raven. He and my bike seemed to communicate as their squawks echoed back and forth over the cold, crisp air. In the silence and solitude of the trail, every sound and interaction was thunderous. My thoughts turned to my grandfather as the majestic bird drifted from one tree to the next, respectfully reminding me of its presence but never intrusive. He seemed to lead me and guide me on, sharing my journey for hours. My grandfather was a Raven, not the spirit animal but the surname. The sleek, brooding bird always carried a deeper meaning for me and our family.

Before long I was in the Window. I had conceived the Window in my head as a way to break up the time and distance and reward myself for progress. This Window was usually about 5-10 miles out from my next goal, whether a village, a checkpoint or a safety cabin. I kept telling myself “just get to the window. Shut up and get to the window”. Once inside the window, that’s when I got real serious with the Gummies. Granules of Gummi Bears disappeared from their baggie like sand from the hourglass. When I rolled into McGrath and the 350-mile race finish line, they were gone.

By the time the last racer finished the 350-mile race to McGrath, 35 racers of the 69 who started had officially scratched. A testament to the physical and psychological impact of the race and the frigid temperatures consistently falling below -30 F.

To Ruby

Day 7 / Mile 375 / -40°C (-40°F)

I left McGrath energized and invigorated, perhaps naively optimistic about my chances of getting through the next 150 miles of trail to Ruby. Or at least getting through unscathed. Prior to the race, I had prepared mentally for the worst case scenario, especially after the events of 2015 when the trail was devoured by snowfall and a drifted trail. But I was convinced that as long as I could get through and rejoin the Iditarod route on the Yukon River I could finish the race.

The trail to Ophir wasn’t perfect, but at times it was incredibly fast. I took advantage and let the Mukluk fly. This year I was determined to ride, to maximize the potential of my bike and let it work its magic. By sunset Martijn Boonman and I had covered 45 miles to Ophir which was essentially a small cabin locked up and protected by electrified wire. This was traditionally the Iditarod checkpoint, now cold and empty, a visible example of the absent sled dog race. An adjacent shed was open and accessible to travelers so we took advantage of the four walls and a roof although any protection from the elements was purely ceremonial.

We woke before sunrise and were immediately crushed by another level of cold. Our shed turned ice box. We couldn’t expose our hands for more than seconds before they stung with pain. Our movements and motivation were dulled but we knew we had to get going and generate some heat. One again the tires were deflating and the pump gave me the middle finger when I attempted to extract it from my frame bag. Martijn exposed his hand for a moment to tinker with his tire core and would pay the price for the rest of his race as his fingers continued to swell from a low-level frostbite.

The ongoing battle with the bitter temperatures altered our strategy. With our arrival at the Carlson Crossing shelter cabin five hours down the trail, we were united with our drop bags piled in the snow. Crows circled above and perched high on the treetops. They devised a plan to steal from the pile of drop bags, stacked like some sacrificial harvest on an alter of snow. We dragged most of the food and supplies inside the cabin for protection. We were able to quickly generate some warmth from the wood-burning fire in the rusted, barrel stove and with a temporary reprieve from the weather we devoured as many calories as we could eat and packed as many as we could carry. Rifling through unneeded drop bags and leave behinds was the classic Iditarod culinary tour and tasting menu. Experimenting with other racers’ abandoned drop bags was a unique perk, introducing me to a buffet of wonderful new products and flavors. I added hot water to some strange white powders, tested foreign brands of dehydrated meals, sipped a can of fruit cocktail and even mulled over the merits of testing either unlabelled red pills or blue, but I wasn’t sure I was ready for what dose of reality those might reveal.

Martijn and I knew a shadow hung over the next stretch of trail and there was no telling how long we would be stuck on it. Fully fed and adequately rested, we set off after midnight, choosing to move through the coldest hours of the day rather than suffer through shivering attempts at sleep. The trail was disintegrating so the light of day wasn’t as valuable to pick or thread a delicate line for riding. It was time to push.

There is a simplicity to the night. Silent. Still. The few sources of light are suddenly and garishly amplified. The halo of light from the headlamp illuminated my tiny pool of existence, casting shadows from the trees performing a theatrical masterpiece of a midwinter night’s dream. Their murky contours bend and shift under the streaming spotlight. The crunching snow under the boots and icy chimes from the joints of the bike create an orchestral overture. The backdrop of the night sky glimmers with the blazing moon, stars and the shimmering, choreographed dance of the Northern Lights. Periodic, reflective trail markers appear like glowing, watchful eyes, city lights or deceiving flickers of hope. This vast, endless landscape sprawling out around me is crushed, condensed down into this tiny stage.

Over time the cold is suffocating. Fatigue exasperates my frustration. In fact, fatigue exasperates all reason. It challenges my decision-making, my patience, will and empathy. As I push deeper into the night and closer to the witching hours a sort of dangerous delusion sets in, an infection of indifference and resignation. I focus to the east and the long black silhouette of landscape, watching and waiting desperately for the first hint of the rising sun. First, the dark indigo bleeding into the inky black night turning a softer blue. Then the warm palette of orange and yellow and pink. And finally that life-affirming, momentous resurfacing of the sun, flooding the landscape like a warm bath, soaking the skin and limbs and spirits, washing away the superficial sting of the cold and extracting the poisonous venom of the deep seeded chill of the night.

In the daylight I could turn my attention and keep occupied with deciphering the ritualistic signs of the local wildlife including the handful of racers in front of me. The consistent stains of bright orange and yellow urine burnt in the snow were reassuring signs of life and a testament to our shared levels of constant dehydration.

For all the surrounding animal tracks through the fresh snow I half expected Noah’s Ark to rise up around each bend.

I tried to imagine the tales behind the crisscrossing prints. The little rabbit’s feet scurrying home for dinner. The wolves silently stalking. The moose stubbornly stealing any semblance of our packed trail leaving an infuriating path of potholes. In a moment of weakness a trail-rage incited me and all I wanted was to find the moose and punch him in the face.

I put my head down and pushed the bike for 18 hours straight, periodically cursing the fact that I habitually pushed on the wrong side given the trail breakers ahead of me clearly initiated a trail with their bike on the right side. No matter, I had expected all of this. I had to endure and whittle away the hours and the miles. Somewhere out there I would be riding again. Before long I left Martijn behind and was on my own again. We both needed to stick to the pace that suited us. We hadn’t seen another soul for days and had no communication with the outside world. There was no knowing if the other racers had made it out or if others followed behind us.

Grasping the scale and isolation of the Iditarod Trail can be difficult. Place names on the map were sometimes only symbolic, abandoned ghost town relics of the past. Ophir, Cripple, Poorman along the northern route and Iditarod on the Southern Route were no more than a shuttered cabin or a backcountry runway buried beneath the snow. No one lives there, no one goes there unless periodically chasing game or gold.

Aside from the makings of a trail, the riders ahead of me offered all kinds of leave behinds, clues to a story that would arouse Sherlock Holmes to froth with delight. Who slept here? When? Whose prints are those? Why? Sprinkles of food that missed someone’s mouth, the fossilized prints of a sleeping mat, a dropped snow shoe, the outline of a fallen rider imprinted in the deep snow off the trail as they surely toppled over in an attempt to ride or simply fell sleep at the wheel. With these puzzles as my only connection to humanity, the isolation of this place sinks in. How fortunate are we to follow this trail alone for days, winding through a secret landscape only we get to appreciate. I feel as though I have been given the keys to a private visit inside an ecological amusement park.

As night set on the second day since Carlson Crossing, I bivvied out on the side of the trail. It’s an awkward and irritable sleep. My Thermarest quickly turns black leather as throughout the night I dream random psychotherapists coming by to judge me on my choices and my sleep set up. No latent message here. A classic “am I worthy” hallucination. The ghosts of my hypo-insomniac, Highland 550 race in Scotland still haunt me. My ability to sleep is still a liability. But in the end, I pass their forensics and scrape together some recovery.

I pack up and push. My carbon fibre frame was starting to feel like lead but I was making progress and my food supplies were dwindling so there was no time to dither. Just move.

And then it happened. Like the edge of a cliff or the distinct shoreline of the sea the unbroken trail transformed into a hard-packed highway. A well-worn snow machine trail from the west converged with the Iditarod Trail going north and all of a sudden I could ride. I lept into the saddle like a maverick cowboy, spurring my fat bike as if every bandit on the Alaskan frontier was at my back.

Nulato

Day 12 / Mile 600 / -36°C (-32°F)

I suddenly became an emotional wreck. I wavered on the trail, flailing like an unreasonable child melting down in the shopping mall. I had ridden fast from Ruby to Galena along a hard packed, windless Yukon River covering the 50 miles in only 5 hours. After a short stop to eat and collect my drop box I set off at sunset for the next riverside village of Nulato.

I was careless earlier in the night, refusing to take the time to shed layers when riding hard and now I was sweating with wet clothes and paying the price. The prospect of bivvying on the river somehow seemed an impossibility. I was at my lowest moment and dreading my existence.

Just get to the window.

Get to the window.

It wasn’t working. My weakened mind saw through its own games. And that’s when I saw him.

Under the moonlight, a small figure fussed and fidgeted at the edge of the trail like a forest gnome. I pulled up unnoticed and startled my fellow biker entranced in his prep for a bivy. I immediately knew I had finally caught up and encountered the elusive Tim Hewitt.

Tim was in a stupor. “Tim, it’s me, its RJ”. I forgot that he had no way of knowing who I was with my face shrouded in layers of merino wool. He grinned, “RJ!” We shared an awkward hug in the darkness on the Yukon River in Alaska.

Tim Hewitt was a non-native species, an invasive Pennsylvanian self-introduced into the Alaskan ecosystem over a decade ago. Since that time, he had come to flourish in this wild and forlorn backcountry and become a signature icon of the race and seasonal fauna of legend and folklore making the great annual migration along the Iditarod Trail.

Tim was attempting his tenth finish to Nome and his first on a bike (he was forced to scratch in 2015 when the trail past Cripple was drifted over by snow). His previous nine completions had all been on foot and he held the record in that discipline. What Tim lacked in cycling talent he certainly compensated for in his unrivaled tenacity, stubbornness and an unprecedented knowledge and experience of the route. I was grateful to share the same trail as him and be there to witness his potential accomplishment.

I had actually shared his first finish to Nome, in 2001, when I was making my film A Thin White Line. I was here now as he attempted to bookend his great anthology of achievements. And rumor had it this was maybe his last time on the trail. Maybe. How many racers had declared prematurely that they were done returning to the ITI and then years later found themselves slogging across a soft, drifted Trail cursing the decision they ever came back?

This seemed to be one of those cursing races for Tim. At times the bike was more an anchor than a tool. Perhaps his newest challenge to finish on bike, making him the first to do so in multiple disciplines, was inspired purely out of legacy rather than levity.

In the moment, standing there on the Yukon River I was simply happy I had found my grubby little angel and the inspiration I needed to push on. I convinced Tim to pack up and follow me, feeding him Werther candies every 15 minutes to encourage him onward, luring him forward with sugar-covered, bread crumbs. Our unexpected meeting motivated us both into Nulato in the middle of the night and we were grateful. A warm gym full of sleeping Iditarod volunteers, vets and media awaited with hot water for our drinks and food. The friendliness of the on duty, Iditarod checker radiated. I tucked under a bleacher, a caveman in his cave and burrowed away in my artificial den for a couple hours of sleep. Weeks on the trail, exposed to the elements and the cold offered a renewed appreciation for my everyday privilege and those carnal needs of warmth and shelter.

Portage

Day 13 / Mile 650 / -35°C (-31°F)

I finished the remaining stretch of the Yukon River quickly and I was grateful to have safely and efficiently passed through another symbolic section of the Iditarod Trail.

I took an extended rest in the school at Kaltag, perhaps too long, taking advantage of my own quiet, warm classroom. I struggled with the decision to stay the night and get one last, solid recovery before the final stretch to Nome. Tim was well behind me, still riding from Nulato and Jay and Kevin were likely camping out in Old Woman’s cabin further up the trail. I could easily get to the shelter of Tripod Flats only 20 miles behind them but I hadn’t yet mustered a competitive edge, still riding on a preprogrammed autopilot, content to manage myself practically with a clear goal of finishing in Nome.

The next day offered a tale of two trails. I left Kaltag before sunrise, wasting time at the Iditarod checkpoint to scrounge up some hot water for the decadence of coffee (and subsequently found my missing drop bag) and followed a musher and his dog team out onto the portage to Unalakleet.

The morning ride to Old Woman cabin would go down as one of my best personal experiences. As the full moon set behind the mountains, the soft glow of morning bloomed through a veil of freezing fog, illuminating a petrified forest encrusted with hoarfrost in a supernatural light. I ripped through the mystical, winter wonderland with an unbridled exhilaration. Before long I passed Tim again who, in true Tim fashion had decided to push on and bivy out on the trail the evening before. Sadly he saw a very different trail. I tried to encourage him before taking off and slipping back into my euphoric dream.

At midday, I stopped at the quintessential shelter of Old Woman cabin for a quick, hot meal. The cabin was still warm from those in front of me and water was still melted in a pot on the stove. Dreams of a final fast stretch of trail and my arrival into Unalakleet and the reward of a large pizza from Peace On Earth pizzeria crept into my head.

But alas, with the warmth from the fully risen sun and a relatively constant flow of snow machine traffic, the once fast, hard-packed trail vanished. The snow was punchy and soft. Soon enough I was forced to push the bike up the hills. Dreams of the ice-encrusted coast and doughy crusts of pepperoni pizza would have to wait.

Only when I arrived in Unalakleet did I hear the news that Kevin Breitenbach was forced to scratch from the race. He had been fighting a stomach bug since the Yukon River and just wasn’t recovering. With all the stress and strain put on the body and the mind, day in and day out along the Iditarod Trail there was just very little margin for bodily malfunction. I had never met Kevin but I was incredibly disappointed for him. He had worked so hard to get here, led the race for so long. It didn’t seem just for it to end this way.

Catching A Break

Day 14 / Mile 725 / -36°C (-33°F)

I left Unalakleet feeling inspired after a great day of riding across the portage and was determined to put in a massive day. The frigid temperatures meant more hard, fast trails and my legs felt like a pair of willowy Iditarod sled dogs, anxious and restless to drive forward.

The sun crested the horizon precisely as I crested the highest elevation of the Blueberry Hills. The sun seemed to be shining on me literally and figuratively. Today was shaping up to be another one of those magical days. Playfully I thought “look out Jay, here I come!”

Except something was wrong under my right foot. An unnatural motion.

Sure enough, at the peak of my exhilaration, my pedal suddenly plummeted to the ground. The flat had broken free of its core. Unfixable. An issue I had suffered before riding across Iceland. I quickly zap-strapped a wool sock in hopes of creating a platform for my foot but that lasted only a few minutes before disappearing onto the trail like another sled dog bootie slipping from a paw.

I had to stay positive and carry on. I pushed the bike more than I liked, pedaling where I could with a sort of typewriter motion, my right foot slowly sliding sideways with each rotation until I was forced to slide back to the beginning to tap out another line. Over and over, bashing out an archaic novel of inefficient progression.

I hobbled into the tiny village of Shaktoolik, a narrow thread of civilization sewn into the arctic landscape. The locals rallied behind my dilemma as I explained my situation at the post office where I collected my drop box of food. A call was put out on the VHF radio asking anyone if they had a bike. A man named Gary seemed to be inspired by the challenge and set off digging out kids bicycles, buried relics rusted from years of neglect under ice and snow. Nothing worked. They were all BMX pedals and wouldn’t fit.

I sent out requests to the outside world and trusted a solution would present itself on the other side of the sea ice in the town of Koyuk. I had already wasted too much time here, hours of problem-solving I should have spent riding and I needed to move on. The single pedal stroke wasn’t ideal but I knew I could still make progress.

Little Mountain Cabin

Day 14 / Mile 775 / -36°C (-33°F)

20 miles outside of Shaktoolik, I rolled up onto the rocky bluff cradling Little Mountain Cabin, an island and sanctuary shrugging its shoulders above the surrounding sea ice and tundra. I was actually still making good time with my one good pedal although I could start to feel the strain on the knee from the awkward stroke. The prospect of crossing the sea ice became a little more daunting.

Outside the cabin, musher Jason Mackey actively performed his ritual of resting and feeding his dogs awash in velvety hues of the setting sun. Inside the shelter, the small stove and supply of wood meant an unexpected warmth. The fable qualities of the scene and my sentimentality lured me inside, betraying any competitive ambitions to push on to Koyuk.

Every moment I delayed I was further shackled to this place. Soon, the sun set and the winds suddenly crept in out of the darkness. And with it crept doubt. The distant lamps of mushers flashed in the night, as an exodus of dogs scampered through blowing, snaking snow.

My window to drive forward closed and divided my intentions. Do I chase Jay and compromise the experience of the trail or do I continue my own journey and compromise the opportunity to race? Little Mountain Cabin became the private forum for that debate.

I was so focused on racing the trail and myself that I wasn’t fully prepared to race someone else. What did that look like? What did that mean? Of course I understood the principle of racing and I was a competitive person but this was somehow different to me. It was a unique position and dilemma. What would I sacrifice? What would I gain? The “glory of victory” seemed ridiculous. Almost selfish, greedy and vindictive. The dynamics of a race were certainly omnipresent and was an underlying force pushing me each day to respect the ding of the alarm clock or hesitate to loiter. But to hunt down a competitor I had never met, had come to respect and was even rooting for jarred my instincts. Fight-or-flight is a natural stress response and physiological reaction. The hunt is something else.

I didn’t know I could catch Jay. I never assumed that was possible. I knew that I felt strong and was riding well. In fact, with each passing day I was almost feeling more energized. But he too was riding steady and was experienced. Not to mention such ‘a nice guy’. I felt like an asshole even considering it. With our positions broadcast online with our Trace devices, all he had to do was mirror my moves. The suggestion to turn off my Tracker, a legal move as the devices weren’t mandated, was douchey to me. We had all committed to the technology, for better or worse. It was up to me to suffer and sacrifice and see what happened. The idea of it was exciting. But the reality of the experiences I might surrender and sacrifice was another matter.

Then there was the issue of the pedal. The one piece of hard fact in all of this. Just before leaving Shaktoolik, I learned a replacement was due to arrive at midday in Koyuk. By midday, if he hadn’t left already, Jay should be far ahead of me.

The very indecision at Little Mountain Cabin had likely already settled the matter. It had cost me the valuable time I needed and could ill afford to waste. I felt at peace with the decision. I only wished I could somehow reach out to Jay and quietly inform of my choice so he could enjoy his powdered champagne-sipping victory ride towards the burled arch of Nome’s Champs-Élysées.

Elim

Day 15 / Mile 850 / -35°C (-31°F)

I crossed the sea ice quickly the next morning and with a replacement pedal successfully supplied by ITI veteran Phil Hofstetter of Nome, I was able to enjoy another fast and rewarding day on the trail. I was at peace with my place in the race and focused on a strong finish and relishing in these final days, potentially my last on the Iditarod Trail. There was no knowing if I would ever be back in this place, by choice or by circumstance.

“JESUS!”

From the darkness, a flock of white birds burst from the bushes as I ride past snapping me from my internal musings. I almost piss myself, so accustomed to absolute silence and solitude. Thankfully there are no witnesses. My bold, bushman status is intact, at least to the outside world.

I roll into the dark, snowy streets of Elim. A group of school kids swarm me and my bike with a barrage of curiosity and questions. I prop up an aspiring, future ITI rider in the saddle, his boots dangling above the pedals. I push him forward as his friends run alongside laughing and cheering. The sudden human warmth is invigorating.

I lean the bike in the snow, next to sacks of dog food and straw and slip quietly inside the firehall and morgue, currently the makeshift checkpoint for the Iditarod. The friendly volunteers immediately welcome me, offer a warm drink and a donut made by a local resident. I oblige, ensuring not to overstep my bounds. There are several mushers milling about in their typical sleep-deprived fog, appearing and disappearing outside to care for their dog team before finally tending to their own needs: food, race updates, sleep.

The lead checker offers a corner on the floor to sleep amongst the other mushers. They aren’t expecting too many more arrivals so there is room in the tight space. I am grateful and accept the offer to share their sacred space.

The evening is perfectly symbolic for me, capping off my Iditarod experience. The mushers respected and appreciated our common goals, not to mention our shared look of exhaustion, dulled movements from the draining effects of the cold and the repetitive, daily routine on the trail.

White Mountain to Nome

Day 17 / Mile 900 / -36°C (-33°F)

I had rested and eaten several courses of food served up so generously by the ITI race angel Joanna Wassilie in White Mountain and was considering an early morning departure but still the presence of Tim Hewitt haunted me. No matter how fast I rode, I pushed, I moved he was always there, lurking in the shadows keeping pace out of sheer savage doggedness. He was simply relentless. Rarely stopping. Never resting until the job was finished. Driven ruthlessly by a single force. Admittedly, I would rest longer and linger in towns and checkpoints to soak up the experience while he wandered off into the night like a ravenous zombie, to lurk and haunt my future trail. He was the ITI’s indestructible slasher, seemingly everywhere, waiting to pounce from around every corner.

I checked Trackleaders and sure enough his little digital dot marched straight through the town of Golovin and onto the river, roughly 20 miles away, approaching my location. I packed up and headed out the door before midnight. With only one last stretch of trail I might as well push on through the night.

The shaft of light from my headlamp refracted in the ice crystallized on my eyelashes and the rim of my hood. The world was reduced to a shimmering kaleidoscope within an inch of my nose.

The face of the steep hills, shrouded in darkness, appeared suddenly in front of me rising up like cresting waves. I bobbed in and out of the swells trusting my bike and the surface beneath me as I let the bike roll. Glimmering particles of frost drifted by in the abyss of night. It was surreal and spellbinding. Despite all those miles and hours on the bike I was still captivated, full of energy and best of all I was having fun.

Each night of my journey I followed the transformation of the moon as it continued to swell. Now, on my final evening it had reached its zenith and I was witnessing not only the end of my own cycling but the end of a lunar one. The giant golden orb rose up from the horizon like a blazing, orange sun, a giant eye watching me soar through this Alaskan aether. I might as well have been riding across an astral plane.

Behind me a flickering and floating light drew closer. I pulled over, respectfully allowing the musher to pass. One-by-one the grinning dogs scurried past, their wafting breath illuminated in the shafts of our headlamp. They had no idea this was their homeward stretch. They just wanted to run. As the last dog past and the sled appeared, a large silhouetted mitt rose up high in the air. I pulled my hand from my pogies and in a moment of human and canine-powered solidarity the musher and I shared a good old high five. We knew where we were. We were close.

I took a final stop at Safety, an isolated roadhouse and the final checkpoint for the Iditarod. The inside echoed with the snores of over-tired volunteers and was shrouded in darkness save the flames from a roaring fire. I laid out my frozen gear to dry and watched the horizon out a window for the glimmer of a headlamp or the rising sun. Either was a cue for me to move on. I had been moving quicker than expected and didn’t want to ride the final stretch in darkness so I took my time to appreciate the warmth. These final moments deserved the light of day.

Several hours later, I rolled down the pavement towards the northern, seaside town of Nome and the Iditarod Trail Invitational finish line. I could have been floating. By now, the turn of the pedals and my engraved position in my saddle was as common and comfortable as the fetal position. It was a final moment of isolation and reflection – an astronaut penetrating the outer atmosphere back into the world of reality. I could finally let go. Let slip my icy armor. Motivated by sleeplessness and a deep soulful satisfaction, peace and pride, an emotion swirled and sweat from my eyes. All that work, all that wonder, all of those miles were behind me. One thousand miles were reduced to this final stretch of forlorn pavement. Collected along the trail were a thousand private moments, ups and downs, challenges and rewards. A thousand faces of emotion, strength, weakness, joy and suffering distilled down into one finish line under the burled arch.

With three experiences to Nome, there are the inevitable questions from others and within myself regarding whether one race was harder than the next. There is no fair answer. In fact, I don’t think it’s a fair question. The Iditarod Trail Invitational presents so many unique variables that quantifying the level of difficulty to me seems pointless. It’s hard. Each year it’s hard for different reasons and harder for some because of the unique variables they may face: sickness, injury, gear technicalities, external forces on the trail, in villages and at checkpoints. So much is consequential. The subtle time differences between bikers and foot racers could expose someone to sudden deteriorating weather or trail conditions and completely change their adventure. Participants don’t return to suffer more, they return to experience more. Everyone goes through their own personal journey. The Iditarod Trail is a choose your own adventure novella, just how difficult that adventure is for any individual is a matter of perception. No matter what the distance, discipline or outcome, whatever year or weather condition, the Iditarod Trail Invitational is just damn hard. The 2017 edition was no exception to that rule. And like so many things that are hard, the rewards are immeasurable. I am grateful for everything this trail has given me.

Tim Hewitt finished in third place, his tenth time to Nome and became the first racer to finish the 1000 mile distance on foot and on bike. He has said this will be his final ITI race. Time will tell.

Jay Cable came first overall, Martijn Boonman finished in fourth place, Petr Ineman and Troy Nyree Szczurkowski shared fifth place.

Retrace the route on Trackleaders.

More photos and tales can be found on Instagram, Facebook and his website.

You can see the files extracted from my Trace device on Strava.

Learn more about the Iditarod Trail Invitational.

Special thanks to: Salsa Cycles for the perfect ride; Arcteryx for keeping me warm and dry; to Nuun for the hydration; Sue’s Jerky for the delicious protein on the trail. To Mighty Riders for all the support and bike tweaks along the way.

About RJ Sauer

RJ is a writer, photographer and filmmaker based in Vancouver, Canada. He loves to explore and connect with new places and cultures around the world on bike and through his work. Follow RJ’s exploration on Instagram @rjsauer and his website www.rjsauer.com