TRP Spyre Review: What Makes a Brake?

With a preference for mechanical actuation, Nic has spent a lot of time with all kinds of mechanical brakes. From his time using Avid BB7s to better days on Growtac Equals, physical cable pull is how he’s come to a stop for over six years. There are some great boutique options on the market these days, but he took a deep dive into one of the more overlooked calipers on the market. Find his full TRP Spyre Review below…

PUBLISHED Aug 19, 2025

Additional photography by Logan Watts

Earlier this year, I dug into the specifics of the Growtac Equal brakes. It was the culmination of years of use, and a caliper I categorize as the best mechanical brake on the market. But there’s another mechanical option that often lingers in the background. One that dotted the budget-oriented builds of so many of my prior bikes, and one that is always there when I’m out of adapters or money: the TRP Spyre. Never noted for its exceptional stopping power, the TRP Spyre—as I said in my Editor’s Dozen—seems to be slightly underrated in terms of its function-to-cost ratio. In my TRP Spyre review, I dove into what makes a brake and why this one is better than I remember.

How TRP Spyres Work

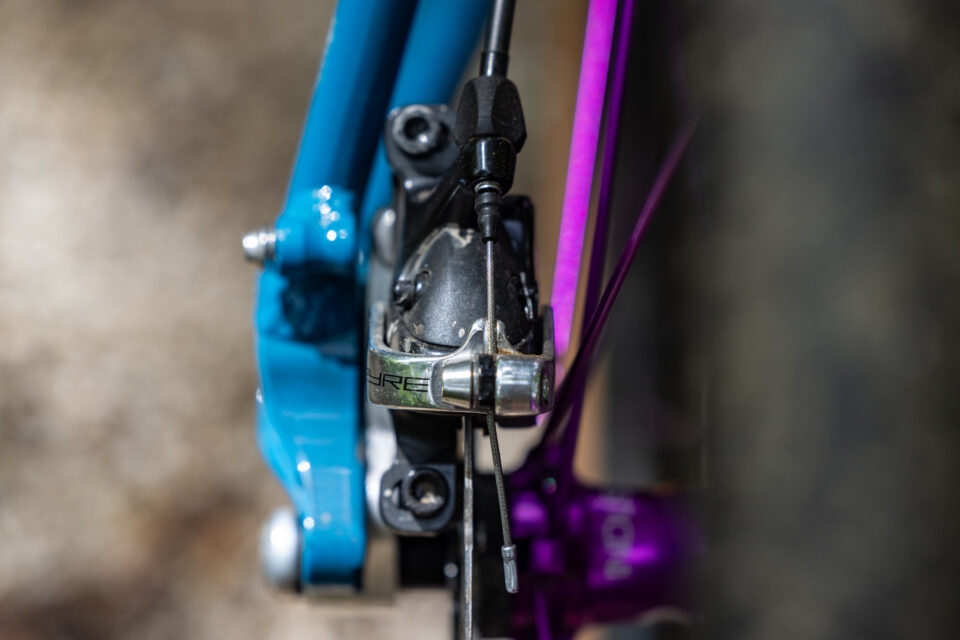

The TRP Spyres operate in the tried and true mechanical design consistent across a range of mechanical brakes, with one distinct twist. Using leverage derived from cable pull, an actuator arm pushes two pads together via a piston and spring. It’s similar to what Paul of Paul Components demonstrates below but with smaller, lower-quality bits, and on both sides. The Spyres use a double-piston design that actuates pad movement on both sides of the rotor, which is a significant departure from most other brakes on the market.

This is because most brakes using this piston and spring design opt for one stationary pad and one moving pad. I’d venture the reasons for this are individual but largely down to two key factors: the space needed to achieve sufficient braking power with the piston and spring design is pretty significant, and doing so on both sides proved difficult in most cases. This is evident in something like the Paul Klamper, where the spring, needle bearing, and mechanism used are so big that they determine the size and asymmetry of the caliper. Most other calipers are much smaller, but they are generally much less powerful, using a similar design.

What makes a brake?

When thinking about what makes a brake feel good, it’s important to dissect the frog a bit. The Growtac Equals, for example, feel “good” for several key reasons: power, lever pull, and return force. If set up right, it doesn’t take much lever pull to induce traction-breaking power from the Equals. To be clear, breaking traction isn’t, in and of itself, a good thing within the action of braking, as you have less grip and thus aren’t slowing down as fast as you would if the wheel were still rolling. But the time at which a rider has the most grip is right before traction is broken.

In the case of the Equals, if less than half a lever pull induces traction-breaking force, being able to induce that amount of power well before the end of the lever pull gives riders the space to dial it in. It also contributes to the feeling that there’s more than enough strength within the system to come to a complete, controlled stop. Brakes that require more lever actuation to induce traction-breaking power might be totally sufficient, but they feel worse given the comparison in feel and lever pull. In my experience with the Spyres and similar brakes like the Avid BB7s, I’ve found that achieving traction-breaking force requires more lever pull.

The other element of “good” braking is return force. In essence, it’s the speed and strength with which the lever returns to its natural position. Part of this is down to whatever levers are used to actuate the brake. I’ve defaulted to the TRP RRL levers for almost every build due to their cost and my ergonomic preference, but a bonus is that they also have a relatively firm and springy lever that aids in mechanical brakes feeling stronger. Run-of-the-mill mechanical SRAM Apex levers don’t have return springs, for example, so lever feel might appear less powerful despite actuating the same amount of force.

Another element in the braking equation is the strength and quality of the internal spring within the caliper. Generally speaking, Klampers and Growtac Equals feel strong, in part, because of their high-quality internals, and thus the strength of the return spring. Brakes like the Spyres, even when aided by a strong lever like the TRP RRL, do not return as quickly or with as much force. It should be noted, then, that strong braking power isn’t directly correlated to the return force felt at the lever. Rather, it’s something that appears in tandem with strong brakes because the mechanism that produces a strong lever feel is typically present in brakes that are going to create sufficient braking power.

For brakes that use a similar internal brake design, the simplistic difference between a Spyre and a Paul Klamper is that Paul Components has upped the quality and size of the internal components to maximize the leverage and effect of a similar design. Spyres sit on the lower end of size, function, and quality in terms of their internals. This isn’t to say they’re bad or insufficient. Just that once you’ve experienced something akin to the return force of a Growtac or Klamper, you might imagine anything lesser is inadequate because of the sensation, not braking performance. I know I did.

So, why Spyres?

Namely, price. Growtac Equals retail at their sole North American distributor, Velo Orange, for $365 flat mount and $405 for post mount (as a set), plus shipping, and they’re often out of stock due to their popularity. Paul Klampers range between $255 and $331 per caliper(!), which puts them well over the Growtacs in even their most affordable configuration. That’s to make no mention of the fact that Klampers, unlike Growtacs, don’t come with any necessary setup equipment. Equals come in sets and include all the required cables and ends for setup. The TRP Spyres, on the other hand, retail at $79 per caliper and don’t range in price between post and flat mount, putting them at a meager $180 per set. Most can find them cheaper online or even at your local bike shop, and the Spyres haven’t accrued the same secondary market hype-flation as the two more expensive counterparts. While Avid’s BB7s are cheaper through most online retailers at around $50, they only come in a post mount configuration and, in my experience, are far less powerful than Spyres.

There’s also the benefit of their size. One major element of strong and fully functioning mechanical calipers is their use of leverage. Mechanical leverage is why the brake feel is stronger in the drops or on any flat-bar lever. In short, there is greater mechanical leverage on the position of the lever in the drops or on flat bars, thus making for better and greater brake feel. Klampers suffer the most in this department, as the sheer size of the caliper makes them a poor candidate for a number of frames on the market. According to their manual, Equals were explicitly designed with this reality in mind, and thus the size of the caliper was made to be as small as possible. The TRP Spyres also benefit from a smaller caliper size, and therefore are less likely to suffer from excess cable bends and poor setup.

While the build quality of the TRP Spyres is noticeably lower than that of their more expensive counterparts, the braking performance, along with the adjustment features, is on par with more expensive options. The Spyres feature a step-less adjustment design, similar to that of the Equals, but without a wandering barrel adjuster. Some prefer the notched design of the Klampers or BB7s, but dialing in pad distance—a key part of setting up mechanical brakes—is more efficient with a step-less design.

Fatal Flaw & Use Case

The Spyre’s biggest design flaw is also what distinguishes it from Avid BB7s, Klampers, and Equals: secondary pad movement. Speaking to anyone about their time with the Spyres, the most consistent issue I noted was the adjustment life. Pads seem to back out quicker and decrease the time at which optimal braking is felt at a certain adjustment point. I’d put this down to the dual-sided design, as the mechanism that moves the pad is more likely to shift than one that uses a static pad and a moving one, but the tradeoff here is negligible when compared to anything in its immediate price range. Moreover, all mechanical brakes require some adjustment after riding because the pads wear and do not self-adjust the distance from the rotor, unlike hydraulic systems.

But, while I’ve never had this issue with the brake, it appears that the pad distance can be vibrated loose by the natural forces a bike experiences during a descent. Again, I’d largely put this down to the nature of the dual-sided moving pad design. Still, Logan noted a significant decrease in stopping power when using the brakes some time ago, and several other users have pointed out similar experiences. Though I have noticed pads backing out relatively quickly on days where I’ve taken to several long descents, it’s not something I’d suggest felt dangerous—simply inconvenient given you have to stop and re-adjust to get back to full power.

Most of the time I spent with the Spyres was on gravel bikes with a lighter load. Aggressive trail riding or riding with a fully loaded rig decreased the time between adjustments because the braking forces are greater due to the added stress and weight on the system. They’re less than ideal for this reason, but they’re still an adequate system in the realm of mechanical brakes. I’ve often found that people’s expectations of their adjustment period are a little exaggerated and predicated on experience with hydraulic systems that didn’t require any adjustment.

- Model Tested: Spyre / Spyre-C

- Actual Weight: 156 grams (per caliper)

- Place of Manufacture: China

- Price: $79 at TRP

- Manufacturer’s Details: TRP

Pros

- Very affordable given the cost of other mechanical options.

- Small caliper makes fitment near-universal.

- Step-less pad adjustment.

- Dual pad movement makes setup and adjustment more modular.

- Options in spec and setup: post, flat, flat or drop bar, carbon arm or polymer.

Cons

- Cheaper internals than competitors.

- Kind of ugly.

- Braking feel isn’t as satisfying.

- Adjustment period is too short for many riders.

- Dual pad movement is a miss.

Wrap Up

The TRP Spyres may never sit at the top of anyone’s list in terms of stopping power or looks, but they’re a solid brake at an affordable price. Given the feedback I received after highlighting them in my Editor’s Dozen, I’d venture these brakes could be made even better when paired with high-fidelity pads and rotors. But, as a stock brake, the TRP Spyres offer solid mechanical stopping power at a price that is dwarfed by the other options on the market. Offered in a variety of options—Spyres, Spyre-C, Spyre SLC, and Spyke—they all feature similar stopping power in an affordable package.

Although I initially stated that I believe the Growtac Equal Brakes are the best calipers on the market, my opinion shifts when price becomes a greater consideration. If dollar per traction-breaking inch is the measure by which you’re making your decision, the TRP Spyres may very well be the best budget brake available.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.