Vivo Enduro Derailleur Review + F3 Shifter

Curious about non-SRAM/Shimano shifting options? Logan put the shiny, small-batch Vivo Enduro derailleur and F3 shifter through 1,000 miles of trail use to see how this combo stacks up over the long haul. Find the full review here….

PUBLISHED Nov 5, 2025

Additional photos by TK Kearns, Lucas Winzenburg, and Mike Sweatman

Since the Vivo Enduro derailleur sits a little outside the mainstream, let’s start with the big picture. I think most of you would agree that, aside from tire size/type and handlebar style, the rear derailleur is arguably the most defining component on a bicycle. It not only distinguishes the character and capability of the drivetrain, but it also serves as a shorthand identifier for a bike’s overall spec sheet. Despite all the other components, how you reference a build setup undoubtedly underscores the derailleur, and not so much the other parts. For example, Shimano XT build, SRAM Rival 1, XTR, GRX 12-speed, X01, and so on. This concept has been slyly adopted by the industry, allowing bike brands to mix in lower-shelf cassettes and cranksets while still using the derailleur as the benchmark.

Beyond its symbolic significance, the rear derailleur is also one of the most mechanically interesting parts of a bike. Unlike static components such as handlebars or cranksets, it’s a dynamic, finely tuned mechanism that performs a meticulous and continuous mechanical ballet—shifting a chain across cogs with speed, accuracy, and precision. It’s the component where engineering and performance intersect most clearly, and it’s also the part that draws the most criticism as it evolves over time. The advent of 10, 11, 12, and then 13 speeds were each met with an onslaught of condemnation, as we’re all well aware. And then came wireless derailleurs, which is the subject of an entirely different conversation.

Non-S Derailleurs

Of course, most bikes in the off-road category are equipped with either SRAM or Shimano derailleurs—I’d say 90 percent of them, if I had to guess, and the other 10 percent might use a derailleur from a smaller brand or have no derailleur at all, running just one gear, a Rohloff internally geared hub, or a Pinion gearbox. For that reason, and because competition breeds innovation, I’m quite pleased to see more options that aren’t made by Shimano or SRAM, and I’m genuinely excited about what seems to be a derailleur mini renaissance happening right now. With the release of Advent and Sword, microSHIFT managed to secure a contender spot; Campy continues to evolve; and even more reassuring, several small “non-S” brands are trying their hand at this complex component with solid outcomes. Madrone, Ingrid, Garbaruk, Rene Herse, and Ratio have each released or teased one in the last couple of years. And, of course, Vivo Cycling from New York launched the shimmery new Vivo Enduro in 2024, which we subsequently awarded with a Gear of the Year spot after being impressed with it on the trail.

However, as new and shiny as the Enduro might look, this wasn’t Vivo Cycling’s first derailleur rodeo. John Calendrille, the brand’s founder and owner, has actually been making rear mechs for nearly 30 years under the Vivo name. The flagship Enduro first saw the light of day in 1996 with the release of 50 eight-speed units hand-assembled by John himself. The O.G. version had a neoprene “Grunge Guard” boot that sheltered the parallelogram from mud and grit, and like a slew of other derailleurs during this golden age of US-made components, the cage and parts were all CNC’d in-house.1 Followed up in 2000, the V1 was cleaned up and made more affordable2 and the V2 was sleeker, with straight cable routing3. In 2002, Shimano purchased Vivo patents covering the mud-shield tech (and likely the V2 routing), effectively ending Vivo’s booted derailleur phase. Later, there was a rumored Hayes collaboration (the “Vivo V5 Enduro”) that never fully materialized. John then pivoted to consulting, showing up on derailleur patents for BOX (Lee Chi) and TRP (Tektro). Despite potential conflicts, the Vivo V5, BOX One, and TRP DH7 ended up notably different in design.4

Vivo Enduro Derailleur Review (V7)

Fast forward many years, and the brand resurfaced with four in-house employees and the seventh iteration of the Vivo Enduro Derailleur —a fully CNC’d, silver 12-speed work of art that’s completely different from any of its predecessors. I’ve now put well over 1,000 miles on it for this review. When I asked John why he released a new derailleur at this point in time, he replied, “I had the design in my head and had to get it out, prototyped, and ridden.”

For me, the lingering question is why we haven’t seen more small-brand, small-batch derailleurs since the experimental CNC boom of the mid-1990s. A few factors stand out: Shimano met most riders’ needs for a long stretch, turning out a run of solid rear mechs; then SRAM took the reins—and several patents—consolidating market dominance through the 2010s and much of the 2020s, until Shimano fired back with legit contenders. Meanwhile, the silent killer, muse, or the straw that broke the camel’s back was a quiet but growing group of riders who bristled at the direction both giants were headed—wireless everything, compatibility woes due to shifting standards for freehubs and pull ratios, and mechs that felt less perfectly simple (or simply perfect) than the classics of yesteryear. That frustration created space—and demand—for alternatives.

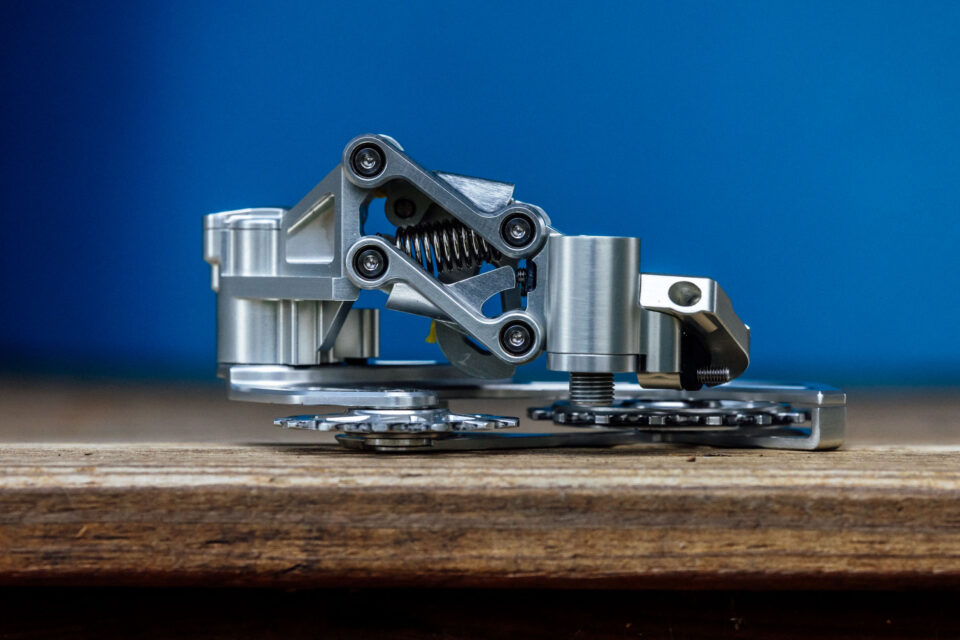

Against that backdrop, whether John admits it or not, the Enduro arrived as a meticulously crafted, artisan answer: a 12-speed, 10–52T capacity, trail-first derailleur with a fully CNC-machined 7075 body, a stiff horizontal parallelogram architecture, oversized 16T aluminum pulleys, and titanium pivots, built from globally sourced parts and assembled in the US. In total, it uses 45 parts (for reference, Shimano’s 12-speed XT RD-M8100 has 37 or 38 individual parts, according to the official exploded view). The complexity and looks don’t adversely affect the Enduro’s performance, however. It weighs just over 320 grams, which is only 30 or 40 grams heavier than its XT/X01 counterparts. It’s also proven to be very reliable, and spoiler alert, it shifts as brilliantly as it looks.

Setup > Long Term Use

You won’t find any how-to videos or chain-length calculators for installing the Vivo Enduro, but anyone who can set up and tune a Shimano derailleur will easily be able to. We went at it blindly and managed to get it shifting smoothly in about 30 minutes. It was a matter of judging the chain length by the wrap in the highest gear, eyeballing the B-gap distance, and fiddling with the cable and B-tension until it was shifting cleanly. I later learned that the included anodized red tool is used to set the B-gap (shown below). At the time, we thought it was just for locking the cage, an ingenious feature that Vivo used to work around SRAM’s cage lock patent, which can also be done using an Allen key if you’re on the road.

One thing you’ll notice on a couple of these photos is that cable routing is a little different. Vivo pre-installs a yellow string to illustrate, and the design is quite elegant. Either way, setup is pretty straightforward, and better yet, I never had to adjust this derailleur since it never went out of tune, even after all those miles. That’s pretty impressive.

The Enduro has a friction clutch that Vivo recommends packing with heavy-duty NLGI #2 grease about every 450 miles. Keeping in true run-it-to-the-ground test-mode fashion, I didn’t service it and haven’t had any issues with sticking. It’s still as smooth as it was on day one. Vivo offers full rebuild kits to replace internal parts, but John says they haven’t shipped any yet because they’ve yet to have a customer report one failing or wearing out.

On the Trail

Generally, I found the Enduro to feel solid and generally sturdier than comparable Eagle and Shimano 12-speed derailleurs, both when handling it off the bike and in use on the trail. This is likely the byproduct of its design. Vivo kept the cage relatively compact by using larger pulleys, and it’s made from machined aluminum. Both of these traits make it inherently stiffer than other long, flimsy stamped cages I’ve had experience with.

Comparing it to others in use out on the trail, it felt like a well-dialed, high-end 12-speed derailleur, but perhaps a cut above what I was used to—hence the Gear of the Year Award last year after I was immediately smitten. It shifts pretty well under load, much like the XT derailleur I reviewed, and it offers similar shifting qualities: clean and precise downshifts and quick, satisfying clunks when moving into higher gears.

Note that the derailleur I tested is technically a pre-production model; the finalized version tightens things up across the board with a more stable frame mount, quicker clutch engagement with titanium hardware, sturdier pulleys with higher-quality bearings, improved clutch sealing, faster cage response, and better sealing at the pivot bearings. And, as of last week, the second-generation model goes a little further with a more robust B-tension screw, a stiffer mounting bolt, some trimmed-down machining for a reduction in weight and mass, and a handful of other subtle refinements.

All that being said, these improvements didn’t fix any real shortcomings, from my experience. In other words, had I published this review prior to learning about these updates, there aren’t any cons I would have noted regarding these upgrades, although a more robust B-tension screw is always welcome. As John mentioned, “Most of the changes from prototype to production are internal components, bearings, sealing… otherwise they are very similar, so whatever [yours] does, the production Enduro will be just a bit better/lighter.”

Speaking of cons, I really only noted one downside for shifting and performance: the metal pulleys. Early on, especially during break-in, they’re a bit loud, and even after they quieted down, I was blowing through chain lube faster than usual. This caused a problem a couple of times. On an overnighter in the Sierra Norte, I skipped packing lube (dry desert, no rain in the forecast—what could go wrong?). I knew we’d be riding a trail that had water, but nothing major; most spots are ankle-deep. After a handful of shallow creek crossings, things got noisy, and by the time we were grinding back up the valley, it was bad enough that pedaling risked snapping the cage. I ended up coasting descents and walking the flats and climbs until I found a bodega and bought a bottle of veggie oil to coat the chain and limp home. Some of this comes down to lousy chain lube choices, but it’s worth noting.

Pros

- Crisp and accurate shifting—as good as they get

- Stays in tune better than any mechanical derailleur I’ve used

- Solid and reliable friction clutch that didn’t require maintenance in 1,000 miles of use

- Ability to lock cage with an Allen key or included tool—an excellent way around patent issues

- Intricately machined, hand-assembled construction

- Derailleur is 100% metal and 100% silver!

- Rebuildable with standard tools

Cons

- Not the quietest derailleur I’ve used (metal pulleys)

- Metal pulleys might require more chain lube—it did in my case

- It would be more difficult to acquire replacement parts when traveling

- Only SRAM shifter compatibility

- Relatively expensive

Vivo F3 Shifter Review

Now that I’ve put the cart before the horse, it’s worth noting that the Vivo F3 shifter wasn’t exactly made for the Enduro derailleur. Quite the opposite, in fact. The F3 was released before the latest Enduro and was designed for folks already in the SRAM ecosystem who were looking to upgrade or replace their shifter with something a little more special. For that impetus, likely fueled by Eagle’s market domination at the time, it isn’t compatible with Shimano derailleurs, and likewise, the Enduro derailleur can’t be paired with a Shimano shifter. Think of it as an artisan lever that can be made for use in the SRAM ecosystem or to forego the Eagle family altogether when paired with the Enduro derailleur and a Shimano XT 10-51T cassette for a SRAM-less drivetrain—which is exactly how I did it.

At $255, the Vivo F3 is priced about $60 above the top-shelf SRAM XX1 shifter, but the F3 is built more like a boutique component. Where most SRAM and Shimano shifters rely on molded plastics and stamped metal parts, the F3 is CNC-machined from 6061/7075 aluminum with G5 titanium hardware, sealed industrial bearings, and 3D-printed polymer paddles. It’s not quite as pretty as the Enduro Derailleur—it was a little clunky at first look—but it’s pretty impressive. And the newest version replaces the plastic plate with a machined aluminum one for more silver goodness. And like the Enduro, it’s completely hand-assembled in New York.

The standout feature of the F3 is its highly configurable fit and feel. You can easily swap between 12 different paddles (six lower and six upper) using a single Torx bolt. Each paddle has a different texture and is assigned a Thumb Reach Rating (TRR) ranging from 0 to 17.5, allowing you to customize how far it is away from your thumb—the higher the number, the more curved the lever is and the farther it is away. I pretty much stuck with a 14 for the upper paddle and 11 for the lower. It fit and felt great, and both were plenty grippy.

Well-designed grip and reach aside, my favorite thing about the shifter ergonomics is the fact that the upper paddle actuates in either direction, taking a cue from Shimano’s high-end shifters and allowing you to upshift with your forefinger. Performance is as expected from a boutique component. It’s solid, crisp, and easily compares to a higher-end XTR shifter or XX1 equivalent. At first, it felt a little large and clunky, but I quickly grew to love it, and it ultimately became one of my favorite shifters for general feel and operation. In short, it has a light touch that matches the derailleur perfectly.

The Vivo F3 has a light, precise feel that matches the derailleur perfectly. It’s kind of reminiscent of higher-end Shimano XT or XTR in that regard. And, the downshift paddle lets you sweep through three or four gears in one motion. Starting in the smallest cog, the first full sweep will move from 2, 3, 4, and 5, then the next is cogs 6, 7, 8, and 9, and the final push goes from 10, 11, and 12. There’s a distinct click with each change, making it easy to confirm how many shifts you engage. Upshifting, or coming down the cassette, the paddle moves one gear per press or trigger pull (more like SRAM; unlike Shimano). It’s fast and kind of feels like Shimano with solid audible shifts.

The F3 weighs 124 grams, including the precision CNC’d 7075 Aluminum clamp. They don’t currently offer any matchmaker hardware for it, which some folks might see as a downside.

Pros

- Ability to upshift with trigger motion

- Crisp and a relatively light touch that matches the derailleur

- Comfortable shifter with the ability to adjust reach/fit and very grippy paddles

- Ability to move through four gears at a time

Cons

- Only SRAM and Vivo derailleur compatibility

- No matchmaker hardware

- Expensive compared to others

- Model/Size Tested: Vivo Enduro Derailleur/F3 Shifter

- Actual Weight: 330 grams (321 for V2)/124 grams

- Place of Manufacture: Globally-made parts, Assembled in US

- Price: $370/$255

- Manufacturer’s Details: VivoArtisan.com

Wrap Up

In the end, the Vivo Enduro is objectively a beautiful, thoroughly engineered, fully serviceable 12-speed derailleur that shifts crisply (and under load), stays in tune, and seems like a long-term solution rather than something that will need replacing. More broadly, it feels less like a compulsory component and more like a manifesto—30 years of mindful investment and tangible proof there’s still room to perfect the rear derailleur. Paired with the F3 shifter—with adjustable paddles and ergonomics that let you dial thumb feel to taste—the system delivers the kind of mechanical tactility and predictability that many riders, myself included, still love.

There are trade-offs. All-metal pulleys are louder (and thirstier for lube), SRAM-only shift compatibility narrows mix-and-match options, and pricing sits firmly in boutique territory; plus you’re buying into a small company with limited availability—although it seems this isn’t a novelty project but a maturing platform. Long-term durability looks very promising, but perhaps it’s still a little early—maybe I’ll report back after 1,000 more miles.

Works Cited

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.