Bikepacker’s Guide to Public Lands (USA)

Share This

Within our global Bikepacking Route Network, we have over 25,000 miles of bikepacking routes in the USA. 98% of these routes utilize federally protected public lands. Whether you’re planning a route or just exploring, here’s what you need to know. Plus, apps and maps to find public lands…

By Virginia Krabill and Logan Watts

Approximately 27%, or 640 million acres, of the total US land area are designated as public lands. 95% of these lands are managed through two federal executive departments—the US Department of the Interior (DOI) and the Department of Agriculture (DOA).* The DOI encompasses the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), National Park Service, and the Fish and Wildlife Service, while the US Forest Service is a bureau within the DOA.

Table of Contents

I. The Whos, Whats, and How-Tos

Agencies, land designations, and bikepacking access information

II. Mapping Public Lands

Maps and applications to identify public and private lands

III. A Brief History of Public Lands

How federal public lands came to be

IV. Where are we now?

Lands under siege and current legislation

V. Help Keep Public Lands Public

Action items you can take to help bring awareness to the threats that face our public lands

The remainder of the country’s total land area (2.27 billion acres) is managed and/or owned by state and local governments or by private corporations and individuals. Gaining access to private lands is difficult. Owners often feel the need to protect their property from abuse/misuse and themselves from potential litigation, so they make it off-limits to the public. As such, American citizens depend on public lands for recreation of all sorts. In fact, 98% of the US-based bikepacking routes we’ve published utilize federal public lands for camping, trails, and roadways. It’s safe to say that without access to federally managed lands, bikepacking wouldn’t exist in the US.

*The remaining 5% of public lands fall under the jurisdiction of the Department of Defense (11 million acres) and an amalgam of various federal agencies.

I. The Whos, Whats, and How-tos

To better understand public lands, here’s a snapshot of the agencies and bureaus that manage them, specific designations applied to various lands, as well as general access guidelines. When planning a bikepacking route, it is always advisable to research the specific areas through which you will be riding. Each agency’s website provides quality information about general land and trail usage and has links to particular properties/parks.

Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

The BLM was created in 1946 through the merger of two federal agencies, the General Land Office and the US Grazing Service. The BLM is mandated to manage public lands for a variety of purposes, including “…energy development, livestock grazing, recreation, and timber harvesting while ensuring natural, cultural, and historic resources are maintained for present and future use” (blm.gov). For most of its history, the focus of the BLM was on resource extraction and management. Then, in 1983, Congress designated the first BLM-managed wilderness area. In 1996, Clinton established Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, the first of its kind to be administered by the BLM. And, in 2000, the BLM’s National Landscape Conservation System, better known as the National Conservation Lands, was established. The BLM administers more public lands than any other agency, with the vast majority (99.4%) located in the 11 contiguous western states and Alaska. In all, the BLM manages 248 million acres, or 10.5% of the total US land area.

The BLM was created in 1946 through the merger of two federal agencies, the General Land Office and the US Grazing Service. The BLM is mandated to manage public lands for a variety of purposes, including “…energy development, livestock grazing, recreation, and timber harvesting while ensuring natural, cultural, and historic resources are maintained for present and future use” (blm.gov). For most of its history, the focus of the BLM was on resource extraction and management. Then, in 1983, Congress designated the first BLM-managed wilderness area. In 1996, Clinton established Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, the first of its kind to be administered by the BLM. And, in 2000, the BLM’s National Landscape Conservation System, better known as the National Conservation Lands, was established. The BLM administers more public lands than any other agency, with the vast majority (99.4%) located in the 11 contiguous western states and Alaska. In all, the BLM manages 248 million acres, or 10.5% of the total US land area.

BLM Bikepacking Access

Biking: Unless otherwise posted, biking is allowed on all BLM land. However, according to data analyzed by The Wilderness Society, 90 percent of public lands are available to oil and gas developers (wilderness.org), while only 10 percent are set aside for recreation, conservation, and wildlife. In those areas that are not for lease, the BLM is working in conjunction with the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) to create more “bike optimized” trails. Blm.gov/mountainbike highlights 20 mountain bike trail networkss, and includes interactive maps and trailhead information. E-bikes are not allowed on any non-motorized trails within BLM jurisdiction.

Camping: Dispersed camping is allowed without a permit on most un-leased BLM land for up to 14 days. The BLM also manages hundreds of developed, for-fee campgrounds.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)

The primary mission of the USFWS, which manages the National Wildlife Refuge Systems, is to conserve plants and animals. Other uses are permitted, including recreation, timber extraction, and oil and gas drilling, but “only to the extent that these activities are compatible” with that primary goal. The USFWS administers 89 million acres of land in the US. When wetlands are included, that number increases to more than 150 million acres. (fws.gov)

The primary mission of the USFWS, which manages the National Wildlife Refuge Systems, is to conserve plants and animals. Other uses are permitted, including recreation, timber extraction, and oil and gas drilling, but “only to the extent that these activities are compatible” with that primary goal. The USFWS administers 89 million acres of land in the US. When wetlands are included, that number increases to more than 150 million acres. (fws.gov)

USFWS Bikepacking Access

Biking: Bicycling is permitted in many of the country’s wildlife refuges. In fact, the USFWS website has a list of recommended bike routes by region. Check it out here. For refuges other than those listed, call ahead to confirm whether they allow cycling.

Camping: Many refuges have paid camping available, the price of which varies by individual campground. Backcountry camping is also permitted within some areas that are managed by the USFWS. Rules vary by individual refuge. To learn more about a specific location, visit the USFWS website and search for refuges by state. Then, click on a specific refuge to see if camping is allowed. To see a selection of some of the refuges that offer camping, visit this page on fws.gov.

National Park Service (NPS)

The National Park Service was created in 1916 to manage the National Parks that Congress had established and monuments proclaimed by various Presidents. NPS-managed properties, of which there are 419 across the country, fall under 28 different designations or names, including National Parks, National Monuments, National Preserves, National Cemeteries, National Recreation Areas, National Seashores, and National Parkways. The NPS operates under the two-fold mission of preserving unique resources and providing for their enjoyment by the public. 3.7% of the country (85 million acres) is designated NPS land.

The National Park Service was created in 1916 to manage the National Parks that Congress had established and monuments proclaimed by various Presidents. NPS-managed properties, of which there are 419 across the country, fall under 28 different designations or names, including National Parks, National Monuments, National Preserves, National Cemeteries, National Recreation Areas, National Seashores, and National Parkways. The NPS operates under the two-fold mission of preserving unique resources and providing for their enjoyment by the public. 3.7% of the country (85 million acres) is designated NPS land.

National Park Bikepacking Access

Biking: Biking used to be prohibited in national parks, other than on paved roads and certain designated routes. Then, in 2012, the National Park Service ruled that individual park superintendents could decide whether to allow bicycles on trails and pathways. Now, there are more than 40 national parks where you can mountain bike on singletrack or dirt roads. This tool on nps.gov allows you to search national parks by activity, i.e. biking.

Camping: Camping opportunities abound in our national parks. Most of the established, paid campgrounds take reservations, up to six months in advance. These sites tend to fill up quickly. Backcountry camping is allowed in most national parks, but permits are required in many instances, and there may be a limited supply. For more details, check out nps.gov and search for the specific park that you will be visiting.

National Trails: The regulations regarding biking on national trails varies. For example, the Appalachian Trail prohibits all bicycles on the trail or the trail corridor, but cycling is encouraged on much of the Continental Divide Trail.

U.S. Forest Service (USFS)

The USFS was created in 1905, making it the oldest of these agencies. Forest Reserves, later renamed National Forests, were originally created to protect lands, preserve water sources and flow, and provide timber. In 1960, those purposes were expanded to include recreation, livestock grazing, and the protection of wildlife and fish habitats “without impairing the land’s productivity” (https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45340.pdf). The USFS manages 193 million acres, or 8.5% of US land area.

The USFS was created in 1905, making it the oldest of these agencies. Forest Reserves, later renamed National Forests, were originally created to protect lands, preserve water sources and flow, and provide timber. In 1960, those purposes were expanded to include recreation, livestock grazing, and the protection of wildlife and fish habitats “without impairing the land’s productivity” (https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45340.pdf). The USFS manages 193 million acres, or 8.5% of US land area.

USFS Bikepacking Access

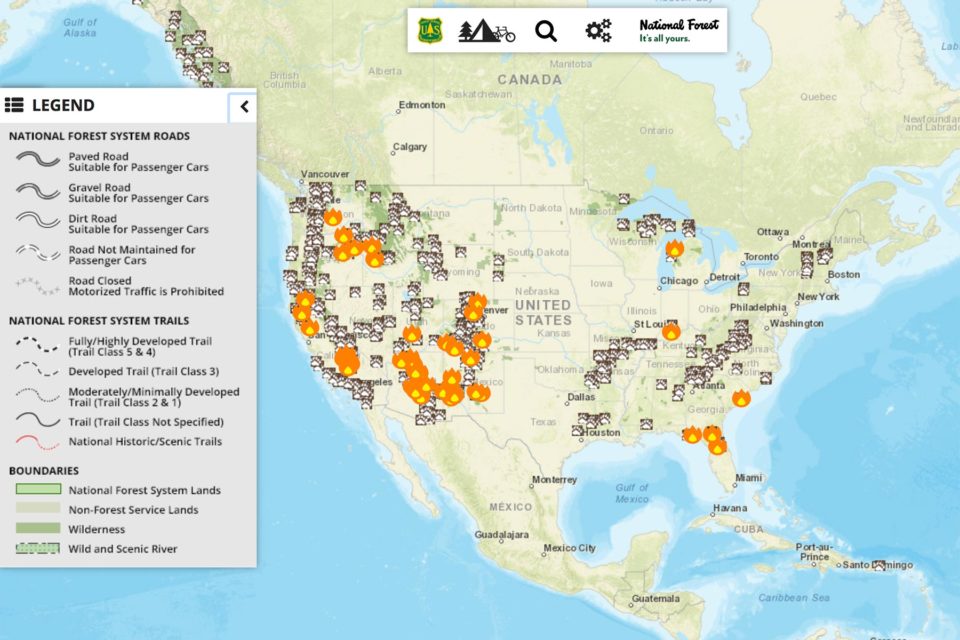

Biking: There are over 158,000 miles of trails in the USFS. 62% (98,400 miles) are open only to non-motorized traffic. 38% are open to motorized traffic, while 20% of the USFS trails are in wilderness areas. Generally speaking, biking is permitted on all national forest roads, in the general forest area, and on horse trails. There are, however, some trails that are designated for hiking only. Use this interactive map to find trail information, including any restrictions on use.

Camping: Many national forests offer designated, paid campgrounds. These tend to be simple sites, with access to drinking water and pit-toilets, but little else. Find a great resource for locating those sites on fs.fed.us. Dispersed camping is also an option, and generally preferred by bikepackers, although some areas in national forests and grasslands are closed to dispersed camping. Where dispersed camping is allowed, a 16 day limit usually applies. Leave No Trace guidelines are to be upheld and you should place your campsite at least 100 feet from any stream or other water source. The best way to find out what areas are open to dispersed camping is to contact the USFS offices in the areas where you will be visiting.

Wilderness and Wilderness Study Areas

Public lands are given titles or specific designations based on a variety of factors, including the value(s) of the property that managing authorities would like to emphasize, whether they be cultural, historical, recreational, scenic, or conservational. Wilderness is the most protected land designation in the US and one of particular importance to bikepackers. Wilderness can exist on any federal land—national forests, national parks, wildlife refuges, and BLM properties—and it can only be designated by the US Congress. There are over 680 wilderness areas in the U.S., making up over 106 million acres (doi.gov). Similarly, wilderness study areas (WSAs) are lands that the agencies have identified as having wilderness characteristics that may qualify them for wilderness designation. These lands are managed “as to not impair their suitability for designation as wilderness” until Congress decides whether to classify them as a part of the National Wilderness Preservation System or ends consideration. In some cases, Congress grants that status to part of a WSA and recommends other types of protections—or none at all—for the rest.

“Mechanical transport” is not allowed within any wilderness area. This includes ATVs, motorbikes, snowmobiles, chainsaws, and, yes, bicycles. In 1964, when the Wilderness Act was originally signed into law, bicycles were not explicitly excluded from wilderness areas. In 1984, after decades of back and forth on what exactly was meant by “mechanical transport,” the USFS announced their “final” decision that bicycles are banned from wilderness. That said, there are various rules and allowances in some wilderness areas, such as gravel access roads where bikes and other transport are permitted. Such is the case along parts of the Camino Del diablo. In these cases, be aware that any travel off the designated roadway is usually prohibited.

The decision to ban bicycles from wilderness is a contentious subject, and one that will elicit different responses from different bikepackers (see Aaron Teasdale’s article here for a thorough breakdown of those arguments). It’s also one that has been challenged numerous times in Washington. In 2016, Republican Senators Mike Lee and Orrin Hatch introduced the Human-Powered Travel in Wilderness Areas Act to the Senate. The bill was reintroduced by Lee in 2018; Representative Tom McClintock of California has a companion bill in the House. If these bills pass, they would, amongst other things, allow local land managers to decide whether to permit bicycles in wilderness areas. Although this potential access may sound dreamy to us bikepackers, many argue that such bills, proposed by notoriously anti-public-lands legislators (see Center for Biological Diversity), are just smoke-screens for dismantling the protections afforded to public lands in this country.

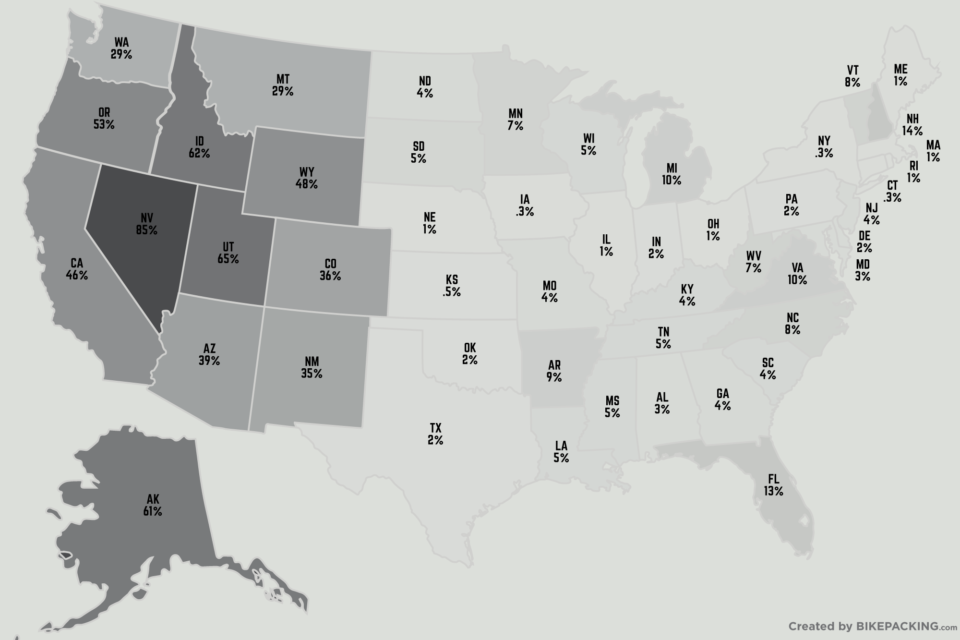

Percentages by State

The map on the right shows a breakdown by state (rounded) showing the percentage of land that’s public, per state. Here are a few other interesting facts:

Percentage of federally managed lands

Alaska: 61.3%

11 contiguous western states: 46.4%

The remaining 38 states: 4.2%

Lowest and highest percentage by state

Connecticut and Iowa: lowest at only 0.3%

Nevada: highest at 79.6%

II. Finding Public Lands

Several tools, baselayers, and mapping overlays have been developed to display public land and land use boundaries. Here are a few that we’ve found useful for planning bikepacking routes and navigation:

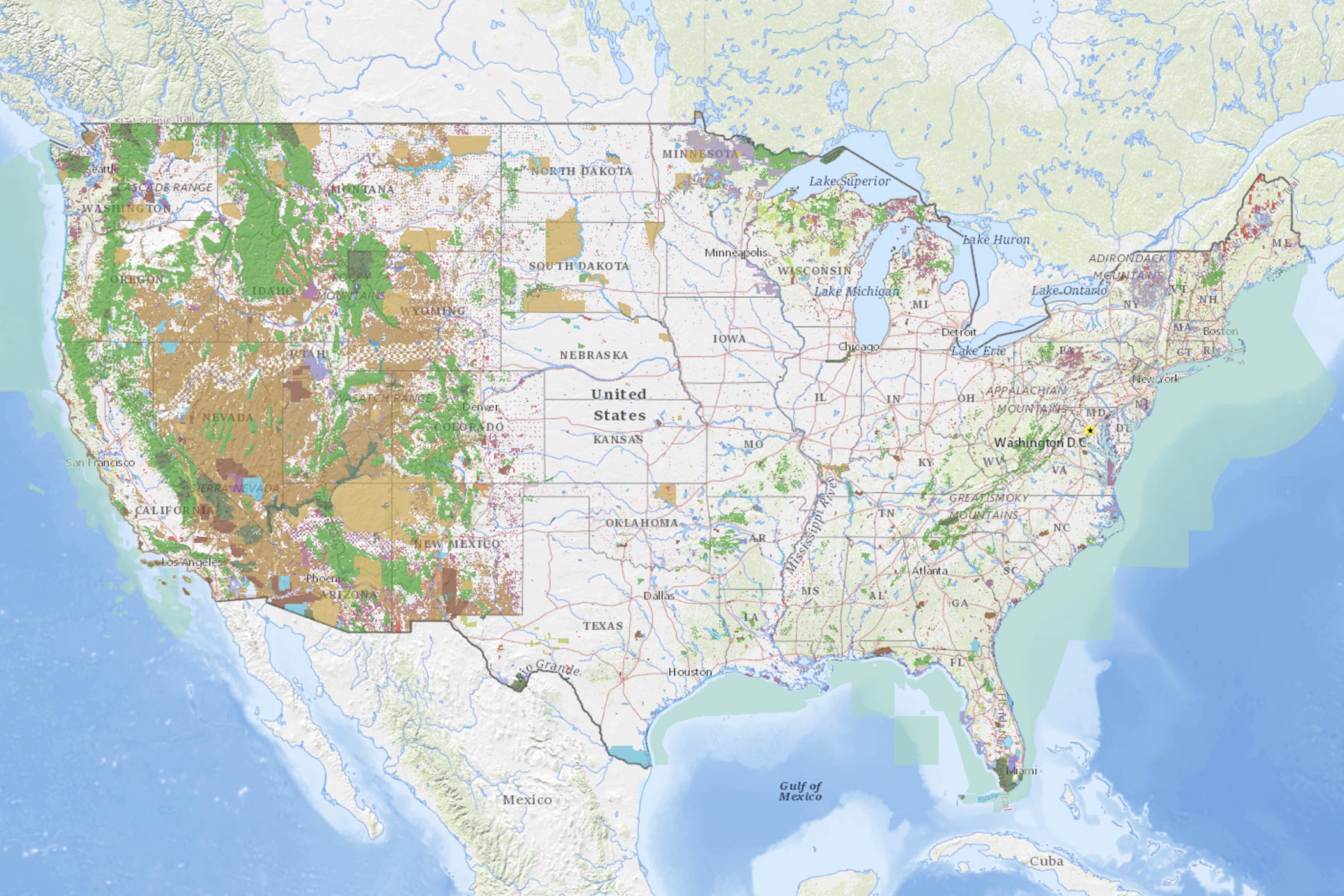

USGS Protected Areas Database

The Protected Areas Database of the United States (PAD-US) is the nation’s official inventory of public open space and private protected areas. The lands included in PAD-US are assigned conservation status codes that both denote the level of biodiversity preservation and indicate other natural, recreational, and cultural uses. Click here to see the map in action.

USFS Interactive Map

The USFS provides an interactive visitor’s map. The map shows roads and trails and highlights notable places, events, and different kinds of recreation and camping areas. The map is searchable, and you can find locations by state or by national forest. Click here.

BLM National Data

The BLM creates and maintains a series of maps and data that are collectively referred to as BLM National Data. These corporate and programmatic datasets help support BLM’s mission to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. Examples of BLM National Data include Administrative Units (BLM state, district, and field office boundaries), National Monuments, and Conservation Areas. You can search many maps here.

App Overlays

Two of the most handy tools we’ve found are within existing navigation apps. Both Gaia GPS and Trailforks offer land use layers that allow you to see where trails and routes fall within the greater land management and private land areas.

Gaia GPS

Gaia GPS offers both “Public Land (US)” and “Private Land (US)” as overlay layers in the app with a paid Premium Membership (well worth the investment, in our opinion—Bikepacking Collective members get a 50% discount). To add these overlays, click the map-layers icon in the app, then select the following to find and activate the layers: Edit > Premium Maps > Overlays. You can then turn on the two layers, and they’ll appear as overlays on the main map.

TrailForks

Trailforks, an app designed for mountain bike trail navigation, also has a land use layer, although it’s not quite as detailed or useful as the option in Gaia. To access the layer in Trailforks, click on the info icon and toggle Land Owner Overlay. Color-coded areas will then show up when zoomed in on the map.

OnX Maps

OnX Maps is an app developed for hunters to identify land ownership. While we haven’t used this app directly, we’ve heard good things. OnX maps show clearly marked property boundaries, public and private landowner names, and more, “giving you everything you need to stay legal and ethical.”

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

The USFWS has an interactive portal that lets you click on a state and view a map displaying many of the refuges and wetland management districts in that state. There is at least one national wildlife refuge in each state and U.S. Territory. About 500 national wildlife refuges are open to the public; nearly all of them offer free entry.

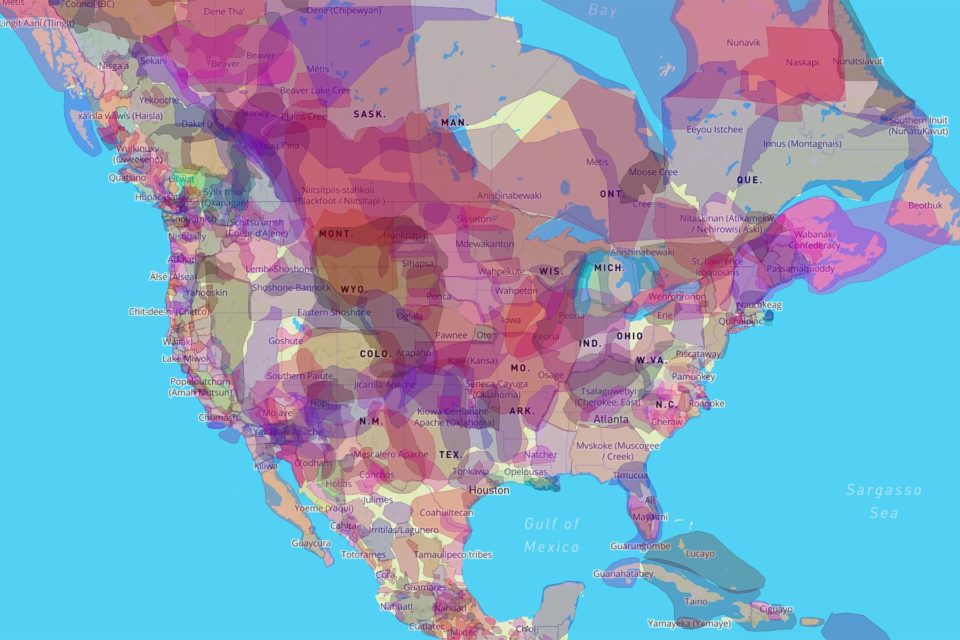

Native Land

Indigenous people populated America well before Columbus arrived and long before there was such a thing as federal public lands. While planning routes or researching historical sites along a route where you’ll be travelling, use Native-Land.ca to see the historical geographic boundaries of indigenous, native lands across the US. Note that you can also identify reservation land within many of the app overlay layers listed above.

This shouldn’t be ignored, as there are different tribal policies related to traveling off-road within a reservation. We recommend contacting authorities while planning your route. Depending on the state, these reservations will greatly dictate where you are able to ride.

III. A Brief History of Public Lands

The history of the United States’ land acquisition is more than a little complicated. To way over-simplify the situation, the lands that make up the United States of America, as it stands, were acquired through a variety of means, including being gifted the land, purchasing it from foreign nations, winning it through war and treaties, and, at times, stealing it.

Federal land ownership began when the original 13 states ceded more than 40% of their “western” lands to the central government between 1781 and 1802. At the time, western lands were those that fell between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. Expansion westward occurred primarily through large-scale purchases from other nations. In 1803, the United States nearly doubled its size with the Louisiana Purchase. The 828,000 square mile acquisition from France was the largest territorial gain in US history. Next, the United States annexed Texas and captured lands during the Mexican-American War (1846-48), extending US territory to the Pacific coast. The Alaska Purchase from the Russian Empire occurred in 1867, adding 586,412 square miles of US territory. Native American lands were initially purchased by the US government and subsequently taken through dishonored, if not completely dishonest, treaties and forced removal.

The government’s disposal of these public lands began shortly after the end of the Revolutionary War. At first, the goal was to raise money for the treasury. The new government was short on cash and needed a way to pay off its debts to its own soldiers and to foreign governments. “Bounty lands” of 100 to 500 acres were issued to eligible veterans who had fought in the Continental Army. Congress also established rules for how land surveys were to be conducted, and the government commenced selling large tracts, 640 acres at a minimum, to the highest bidders, primarily financially-backed speculators and corporations. Later, laws were passed that lowered the acreage requirements and set up a system of installment payments, making it more feasible for some homesteaders to join in on the “American dream” and move westward. Still, the price of land was well out of reach for most individuals.

In the mid-1800s, the disposal of federal lands shifted purpose from padding the treasury to satisfy the notion that white, Christian Americans (not Native Americans) had a “manifest destiny” to settle the continent. Land grants that supported public education and the development of a transportation infrastructure (railroads) were issued. In 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Homestead Act, which gave settlers 160 acres of public land in exchange for a modest filing fee and a guarantee to complete five years of continuous residency. All of these entitlements were highly successful; settlement and expansion in the west proliferated.

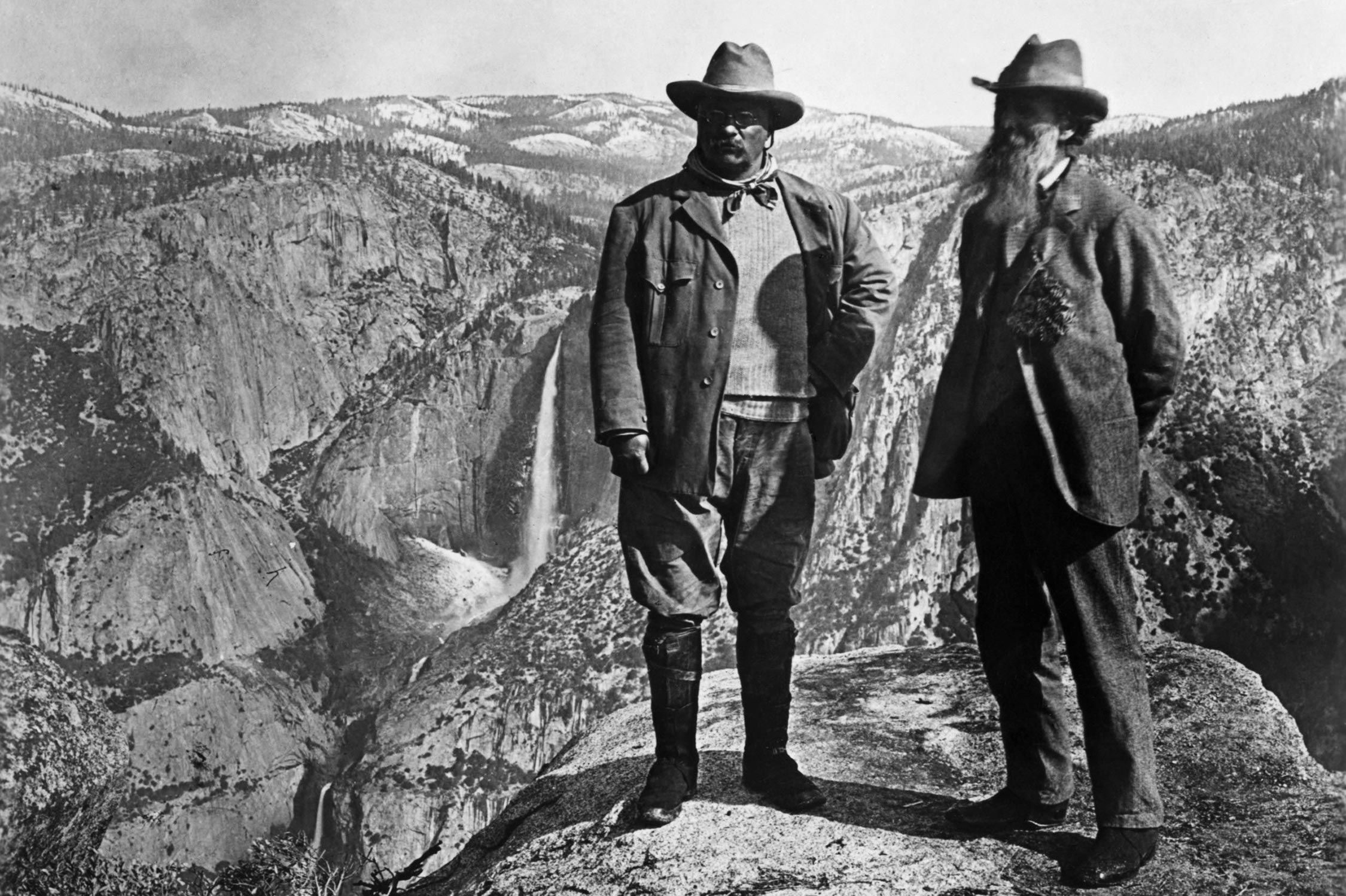

The Conservation Movement, as part of the larger Progressive Movement, led to changes in government policies about conservation and public lands. New laws established national parks and forests and offered protections for fish and other wildlife. During Roosevelt’s term as president (1901-1909), approximately 230 million acres of public land came under federal protection. He established the USFS along with “150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, 4 national game reserves, 5 national parks, and 18 national monuments” (nps.gov). Teddy, aka the conservation president, left a legacy which was proudly built upon by many presidents who succeeded him. Throughout the brief history of the United States, executive actions have been taken to protect and improve public lands. During his presidency, Barack Obama passed executive actions that extended “permanent” protections to over 550 million acres of land and water in the country, leaving the largest conservation legacy of any president to date.

IV. Where are We Now?

In December of 2017, the Trump administration reduced the size of two national monuments, Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, by more than 2 million acres, the largest elimination of protected areas in U.S. history. While this act garnered a lot of attention, the debate over federal land policy has persisted for centuries, often pitting conservationists against corporations and national interests against local ones.

It’s difficult to ignore the partisan nature of these debates and a challenge to write about the issues without interjecting opinion. That said, the war over public lands and their administration has intensified over recent years, and it seems that big business, namely the fossil fuel industry, has gained the upper hand. According to the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, the BLM, under Trump’s administration, has auctioned off seven times more public lands than Obama did over a similar period of time, the vast majority going to the oil and gas industries. Not only is the fossil fuel industry leasing our lands at outlandishly low prices, as little as two dollars per acre, the royalty rate the government “charges” is only 12.5%, a rate that has not increased since 1920. With such incentives, an eager administration, and complicit legislators, the industry is gaining access to ever-expanding territory, including some of our most pristine and sensitive landscapes.

To make things worse, the way that these lease sales take place is undermining public input. Auctions used to take place in a public forum; now, all BLM oil-and-gas lease sales are managed and conducted via EnergyNet, a private, Texas-based online auction company that prohibits the use of its site by average Americans. What’s more, government officials have decreased the public comment period from 30 to 10 days.

With all of the bad news about our public lands (and weakening environmental protections), the recent passage of the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act offers some hope. This law designates 1.3 million acres in Utah, New Mexico, Oregon, and California as wilderness, which may not benefit the sport of bikepacking but is a win for those of us who care about conservation and the environment. The law also adds protections for more than 1 million acres of public lands from future mining operations and, most importantly, permanently reauthorizes and funds the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

While we applaud this bipartisan bill and the protections it affords, there should be no doubt that our public lands are still under threat.

Recent Legislative Attacks on Public Lands

The most egregious attempts in recent years took place during the 114th and 115th Congresses. In fact, the 115th Congress established a rule that “certain conveyances of federal lands” would “not be considered as providing new budget authority,” making it a lot easier for those lands to be transferred or sold-off, as they were deemed essentially valueless. In January 2019 a new Congress convened, one with a more ideological and political balance than the previous two. As a result, the legislative assaults on public lands have greatly diminished this year. The biggest lesson that might be taken from this is that every election counts. Your voice matters. VOTE.

The following list is not all-inclusive. It is just a sample of some of the Congressional legislation that has been proposed in an attempt to sell-off our public lands, limit their accessibility to the public, and/or strip regulations and governances that are in place to protect them. It is organized by year that the bills were proposed. In some instances, the same anti-public lands bills have been proposed on multiple occasions. HR and S denote bills that were introduced in the House and Senate respectively. None of the proposed bills in this list have been signed into law; most haven’t even been passed by their prospective chambers. The mere fact that they were introduced, however, reflects the anti-public lands values of their authors and co-sponsors and should strike fear in the hearts of anyone who loves spending time in the great outdoors.

2011

HR 2852 / S1524: Action Plan for Public Lands and Education Act of 2011

This bill makes the amount of land granted to each state 5% of the number of acres of federally owned land within that state as of January 1, 2011.

2012

S 2473: Federal Land Designation Requirements Act of 2011

This bill prohibits the designation of national forests, national parks, national wildlife refuges, national wild and scenic rivers, national trails, and wilderness areas unless there is state legislative approval.

2013

HR 638: National Wildlife Refuge Review Act of 2013

This bill amends the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966 to prohibit the Secretary of the Interior from establishing any new national wildlife refuges, except as expressly authorized by a law enacted after January 3, 2013.

HR 2657: Disposal of Excess Federal Lands Act of 2013

This bill directs the Secretary of the Interior to offer for disposal by competitive sale certain federal lands in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming. Requires the Secretary to submit to Congress: (1) a list of any identified federal lands that have not been sold and the reasons why they were not sold; and (2) an update of a specified report, including a current inventory of the federal lands under the Secretary’s administrative jurisdiction that are suitable for disposal.

HR 1459: Ensuring Public Involvement in the Creation of National Monuments Act

This bill amends the Antiquities Act of 1906 to subject national monument declarations by the President to the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) and prohibits the President from making more than one such declaration in a state during any presidential four-year term of office without an express act of Congress.

S 2004: A bill to amend section 320301 of title 54, United States Code, to modify the authority of the President of the United States to declare national monuments, and for other purposes.

This bill declares that any proclamation of a national monument or reservation of a parcel of land as part of a national monument shall expire three years after the proclamation or reservation unless specifically approved by: (1) a federal law enacted after the date of the proclamation or reservation; and (2) a state law, for each state where the land involved is located, that is enacted after such date.

2016

HR 4751: Local Enforcement for Local Lands Act of 2016

This bill terminates USFS Law Enforcement and Investigations and discontinues the use of USFS employees to perform law enforcement functions on federal lands. Instead, the care and protection of national forests is handed over to local law enforcement.

2017

HR 622- Local Enforcement For Local Lands Act

This bill declares that the DOA shall terminate the USFS Law Enforcement and Investigations unit and cease using USFS employees to perform law enforcement functions on federal lands. The bill also states that the DOI shall terminate the BLM Office of Law Enforcement and cease using DOI employees to perform law enforcement functions on federal lands.

HR 232: State National Forest Management Act of 2017

This bill directs the DOA, through the USFS, to convey to a state up to 2 million acres of eligible portions of the National Forest System (NFS) that the state elects to acquire through enactment by its legislature of a bill meeting certain criteria. Portions of the NFS conveyed to a state shall be administered and managed primarily for timber production. This bill was formerly introduced in 2015 as This bill was formerly introduced in 2015 as HR 3650: State National Forest Management Act of 2015.

S 33: Improved National Monument Designation Process Act, S 132, and HR 2284 (all related bills)

This bill states that, a national monument can be designated on public land, the President must obtain congressional approval, certify compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA), and receive notice from the governor of the state in which the monument is to be located that the state legislature has enacted legislation approving its designation.

S132 / HR 2284: National Monument Designation Transparency and Accountability Act of 2017

These bills require the President, before a national monument can be designated on public land, to obtain congressional approval, certify compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA), and determine that the state in which the monument is to be located has enacted legislation approving its designation. The bill prohibits the DOI from implementing restrictions on the public use of a national monument until the expiration of an appropriate review period providing for public input and congressional approval.

HR 243: Nevada Land Sovereignty Act

This bill prohibits any extension or establishment of national monuments in Nevada except by express authorization of Congress.

HR 4239: SECURE American Energy Act

The bill allows states with an established permitting and regulatory programs to manage certain federal permitting and regulatory responsibilities for oil and gas development on federal lands within their borders. It also limits the President’s authority to prohibit oil and gas leasing on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).

HR 4568: Enhancing Geothermal Production on Federal Lands Act

This bill amends the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970 to allow the DOI to award noncompetitive leases on up to 640 acres of certain federal land for geothermal development. The bill exempts geothermal exploration test projects from complying with environmental review requirements under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA).

S 49: Alaska Oil and Gas Production Act

This bill authorizes the exploration, leasing, development, production, and transportation of oil and gas to and from the Coastal Plain of Alaska. The bill requires the BLM to establish a competitive oil and gas leasing program for oil and gas exploration, development, and production on the Coastal Plain. The bill amends the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act to repeal the prohibition against production of oil and gas from the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The bill prohibits the BLM from closing land within the Coastal Plain to oil and gas leasing, exploration, development, or production except in accordance with this bill. The BLM must conduct a second lease sale in Coastal Plain areas within 18 months after the first lease sale is conducted under this bill.

2019

HR 179- Acre In, Acre Out Act

This bill prescribes a new requirement for any acquisition of land by the DOI or the DOA that would result in a net increase of total land acreage under the jurisdiction of the NPS, the USFWS, the BLM, or the USFS. The department concerned must offer for sale an equal number of acres of federal land that are under the same jurisdictional status.

2020

The Great American Outdoors Act

The Great American Outdoors Act passed, providing $900 million each year for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), which was enacted to help preserve, develop, and ensure access to outdoor recreational resources for American citizens. It will also create a new National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund, which will provide up to $9.5 billion over five years to address the backlog of maintenance projects in our National Park System and on other public lands.

Conversely, the The Trump administration and their allies continue their attack. Most recently, the administration cleared the way to open the country’s largest national forest to more development and logging—the Tongass National Forest in Alaska. “The rule change would make the forest’s 168,000 acres of old-growth and 20,000 acres of young-growth available for timbering. The forest plays a major role in the battle against climate change: The Tongass is an enormous natural carbon sink, holding an estimated 8% of all carbon stored in U.S. national forests.” – NPR.org

V. Help Keep Public Lands Public

Stay informed about various legislation regarding US public lands and make your voice heard:

- Keep track of various legislative issues that affect public lands

- Track new legislation

- Sign this petition

- Call or write your senators and representatives by texting your zip code to 520-200-2223 (or congress switchboard: 202-224-3121) to get connected

- Get involved in your local government and attend town hall meetings

- Stay informed, spread the word on social media, and vote!

- This website shows some of the lands available for exchange or sale by the BLM.

- Make your voice heard by submitting comments to the BLM NEPA register.

- Follow the #public-lands tag on this website. We’ll post updates as we learn about them. And if we miss something, be sure to let us know.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.