Could “E-Bikepacking” Become a Thing?

As we’ve seen over the last five or so years, e-bikes have gained a solid footing in the bike marketplace and attracted many new riders, but can they become a mode of transport for bikepacking trips? In our latest video, Neil delves into several details in hopes of finding an answer to that question…

PUBLISHED Mar 19, 2024

Just last week, Salsa launched its new range of e-bikes, and it got all of us thinking about how this fits into the adventure cycling world; after all, Salsa has dedicated its brand to backpacking bikes and “adventure by bike” for well over a decade. While Salsa’s release of these new models may have been the impetus to create this video, plenty of other brands have already developed e-bikes with a similar intent. We’ll get into that at the end of this video, but just by searching “adventure e-bikes” in Google, you’ll find yourself in a strikingly unfamiliar world.

That reminded me of how out of the loop I—and the rest of the BIKEPACKING.com team—am when it comes to e-bikes. This isn’t something we did on purpose, exactly, but we have always (and will continue to) put human-powered travel at the forefront of what we do. But to better understand if e-bikepacking is even possible and what its future might look like, we need to discuss a few things, regardless of whether all of us are on board with the idea or not. Watch the video below, and read on for a written version.

Types of e-bikes

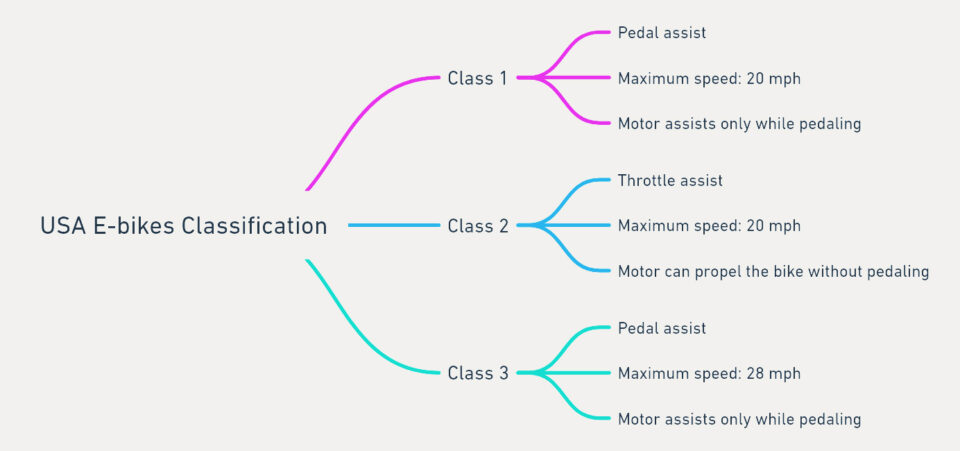

First, we need to understand the different types of e-bikes and how they’re classified, which varies by country.

Here in the United States, there are three main classes: Class 1 provides pedal assist up to 20 mph, Class 2 offers throttle assistance alongside pedal assist up to 20 mph, and Class 3 extends pedal assist up to 28 mph. Simply put, classes 1 and 3 require pedaling, while all you need to do for class 2 is press a throttle and go.

In Canada, motors are limited to a 500-watt output and can’t travel faster than 32 kilometers (20 miles) per hour on motor power alone on level ground.

In Europe, e-bikes are typically limited to 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) per hour with pedal assist only, no throttle. Going faster makes it a Speed Pedelec, requiring registration and plates. Motors are capped at 250 watts, with some exceptions like “Boost Modes.” However, the UK may soon raise this limit to 500 watts. Compared to the US, European e-bikes are slower and less powerful but widely accepted and can be ridden almost anywhere without much controversy.

E-bikes also differ based on the bike’s electric motor location; you will see two main types of e-bikes: 1. mid-drive, where the motor is located and built into the bottom bracket; and 2. hub drive, where the motor is in the rear or sometimes front hub. The lightweight and compact design of the hub drive gives bicycle manufacturers more freedom and, as you can see here with the Confluence, makes the bike look much more conventional, but generally, hub drive e-bikes are not as powerful. Each one of these bikes also comes with one of many drive brands; for example, there are a lot of mid-drive motors such as Bosch, SRAM, Shimano, and others. It’s worth mentioning that there are also aftermarket kits available to turn existing bikes into e-bikes and back into non-assisted again. Cass has successfully done this using the Bafang mid-drive motor on a Jones.

Batteries

The most significant variable among e-bikes is the battery life, which dictates ride time and distance and recharging logistics. This is where things start to get complex, and if you value the freedom of simply riding your bike and camping wherever you want, a battery-powered bike might not be for you. Things that affect battery range are weather, rider/rig weight, terrain, throttle usage, cadence, and riding speed. But to get a better idea of what to expect, you need to understand what battery/drive system you are using.

Range

Since Salsa used the Bosch motor system, in the video I plugged the Tributary specs into the Bosch range calculator using conditions I often find myself in. I would say I’m around 190ish pounds with a loaded bike. The Tributary has a performance line mid-drive system and a PowerTube 625 battery. It appears we are on an “upright road bike” with cross-country tires, and I plugged in conditions I find in my backyard here in Colorado during the summer. I guessed I would be going about 12 miles per hour, and for kicks, I just set the auto-riding mode on. Bosch says I would likely get around 34 miles, and when I add the range extender, that gives me almost 50 miles.

Now, I know this is a case of “a lot depends,” but it should give you a good idea. You could get more in the eco mode in perfect conditions or much less in turbo mode in less-than-ideal riding conditions. We could really get into the weeds about this a bit more, but simply put, no ride or e-bike is the same, and a lot depends on the specific battery and motor, the way you ride, and the conditions you ride it on. This might be a reason why some manufacturers simply don’t even share the max range of certain bikes.

Recharging

Recharging is another factor that might make you rethink a trip, as you’ll need a way to recharge your batteries to continue moving with assistance. You can still pedal an e-bike without using a motor; but bear in mind that some motors exhibit significant drag, and with the added weight, it’s much more challenging without the assistance of the motor’s power. This means you must bring a charger; some work faster than others, and some are larger than others. My Bosch 4a charger comes in at just under 800 grams and is the size of a water bottle—that’s not light or small.

Once you get a good feel for your battery range, you can better understand how far you can go between stops. While I sometimes find myself in hotels on trips, 90% of the time, I camp in the woods or under the stars, which I strongly prefer while bikepacking, and I know I’m not alone. E-bikepacking opens a different style of travel, one where you might consider riding from lodge to lodge or hotel to hotel or even to more developed campgrounds that have outlets to recharge your battery each night. Depending on the battery drain, capacity, and charge time, this could take up to a whole night with some of the largest batteries available. And while there are chargers to charge batteries rapidly, it’s best for the battery’s lifespan to slow charge them.

Overall Weight

Obviously, the more weight you have, the more energy your e-bike will use to carry you forward. When we think about adding up to 30 pounds (or 14 kilograms), that’s a significant amount and will certainly take up more battery life. I’m sure there’s a more precise way of calculating this, but again, this is an introductory video, so I won’t dive into that today.

e-bike regulations

In the United States, regulations regarding e-bikes vary by state and locality. Generally, e-bikes are allowed on roads and streets where traditional bicycles are permitted. However, access to bike paths, trails, and other recreational areas may depend on the classification of the e-bike. Class 1 and 2 e-bikes are typically permitted on most trails and paths, but restrictions may apply in particular areas.

An excellent example of this is locally here in the Gunnison National Forest, where e-bikes are allowed on all motorized trails where dirt bikes are permitted but off limits to non-motorized trails. That said, it might not be as cut and dry in other areas. Class 3 e-bikes, with their higher speeds, may face more stringent regulations depending on your location, such as Colorado, where class 3 e-bikes aren’t allowed on bike paths due to the faster speeds they can travel.

E-bike Friendly Routes?

What has to be considered for bikepacking routes to be e-bike-friendly? This will require some homework, but as I mentioned, if you wanted to ride the Great Divide MTB Route, the bike path section in Colorado from Silverthorn to Breck is off-limits to a class 3 e-bike, such as The Salsa Tributary, so you would need to ride with traffic. However, Class 1 e-bikes such as the Salsa Confluence can ride that path. You must also find supplemental charging, as many stretches on bikepacking routes are 100+ miles between resupply.

In Europe, as I mentioned, e-bikes are much less controversial. In fact, many places have already built infrastructure around them. Some places in the mountains there, like the Dolomites, are completely set up for e-bikes, with charging ports in huts and public charging zones in some places too, which you could integrate into a bikepacking trip. That said, e-bikes work really well in Europe because the distance between chargers is often shorter. This all means it might be difficult to plan a trip on an already established route without doing some serious planning here in the United States. I would think the upside here is that you can likely lower your overall travel time, as e-bikes are certainly more efficient and faster from A to B. That approach might allow a bit more downtime where you can charge your bike or take a more extended lunch break in a town and get back on the bike to your next outlet.

Finally, e-bikes often require more maintenance. Not only are there moving parts, but limited-life parts like chains and brake pads will wear out faster, so if you’re on a more extended trip, you may need to pay more attention to that.

e-bikepacking as a tool

All that said, one benefit of an e-bike is using it as a tool to enable bikepacking routes—think scouting routes or trying to find out if a road goes through without as much effort. I could see where folks could use an e-bike for this reason and a slew of others, such as helping get folks on bikes who otherwise couldn’t, getting out to a trail work day without access via roads, or using cargo bikes that replace vehicles. As a commuter, I’ve been using a Surly Big Easy for the better part of three years. In the summers, it truly replaces a vehicle, picking up groceries, doing chores around town, dropping off packages at the post office, and picking up our kiddo from daycare.

But e-cargo bikes can also double as family e-bikepacking rigs or for dog hauling, as Cass has demonstrates. This also means you may not need to go and drive out to a trailhead but rather just pedal out of town on the e-bike with ease before getting into the good stuff. Not only is it more rewarding riding from your front door, but you don’t have to worry about parking your car overnight at a trailhead. So, whether you’re on a cargo bike or using your e-bike for around-town commuting or errands, these things are extremely useful.

The best e-bikes for bikepacking?

This all begs the question, is there a good e-bike for bikepacking? And if so, what kind? Obviously, like any sub-genre of bikepacking, it depends on the type of riding you plan on doing. But there aren’t many options optimized for bikepacking just yet, and when I say this, I mean performance-based bikes with big-volume tire clearance, stable geometry, and extra-long battery life. The new Salsa Tributary seems like a good option for a quick overnighter out of town or if you can plan a trip around recharging every 30-50 miles. The bike clears 2.6” rubber and generally looks like a capable bike for dirt road excursions. Another really intriguing option is the Specialized Turbo Creo 2 Comp, which has 2.2” tire clearance and a claimed 120-mile range in ideal riding conditions and bike settings (but much less from the research I have done in suboptimal conditions, or let’s say, my ideal conditions).

There are a number of e-bikes in the gravel category, such as the Niner RLT E9 RDO that comes with a 500 watt-hour battery. The Kona Libre EL is another option that’s a bit lighter than many of the drop-bar e-bikes but is a class 1 with a 500Wh Shimano battery. The Cannondale Topstone Neo is another that springs to mind. Then there are hardtails, which actually offer some of the best geometry for mixed-terrain bikepacking routes, but if you’re riding more steep, techy climbs, the battery life tends to be much shorter. A few options that look promising include the Orbea Urrun, Kona Remote, or the Trek Powerfly 4, but the market is also saturated with e-bike-specific brands. If it were me, I would stick with a brand that has a history of putting together acoustic bikes.

In my opinion, all of the above-mentioned bikes simply don’t quite cut the mustard. Ideally, there would be a bike that has an average range of 50 miles in hilly or mountainous terrain. I know that puts a lot of pressure on the battery, but that’s what I think would be a good baseline before I take one out on an e-bikepacking trip. If I did plan a trip with an e-bike, I would need to rethink my goals and how I conceptualize bikepacking—on my normal trips, I don’t always find myself in towns every day.

I appreciate the infrastructure being built and developed in Europe, but similar opportunities don’t seem to be fully fleshed out in other parts of the world. I certainly don’t foresee the industry making more dedicated e-bikepacking bikes just yet, but I do see improved run times being a priority, so maybe we will see something more apt for bikepacking down the road.

What do you think about the future e-bikepacking? Have you done it, or would you? What else am I missing? I invite you to let me know your thoughts in the conversation below.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.

We're independent

and member-supported.

Join the Bikepacking Collective to make our work possible: