Alone in the Empty Mountains: An Ode to Route Building

Whilst looking back on a solo trip through Spain’s Serranía Celtibérica, Cass considers the transformative power of route creation, from its ability to inspire others in the bikepacking community, to the way it can help us use bicycles as tools for connection, education, and change…

PUBLISHED Apr 9, 2021

A couple of weeks ago, I watched Sergio Luna’s long-form film recounting his experiences on the Montañas Vacías bikepacking route. His images and social reportage took me straight back to my time in Spain’s Serranía Celtibérica, an area that’s both beautiful and forsaken in equal measure. It made me consider, once more, the history behind this region’s sense of abandonment and the ensuing quietness that now envelopes it. Because after years of depopulation, the Spanish Lapland – as it’s sometimes known – is almost devoid of humans.

I never found the time to reflect on my time there, in part because the trip was somewhat impromptu. I’d originally travelled down to Valencia with the intention of riding the Burrally. But halfway through, whilst camping outside the climbing hotspot of Chulilla, I found myself hankering to strike higher still into the mountains – towards the Montes Universales, a range that marks the southeastern terminus of the Sistema Ibérico. Then the penny dropped. This oft-overlooked area was also home to Montañas Vacías, a brand new route that had piqued my online interest, in part because of its sumptuous presentation. Noting that its eastern edge lay just a couple of days’ ride away, I reminded myself that despite the goals we may set, we’re only bound by our own rules. So, I turned my handlebars northwards instead, towards the Parque Natural de la Serrania de Cuenca. “Halucinante,” enthused an old and wiry climber, when describing it.

By then, I knew I wouldn’t have time to ride the complete route but at least I could get a taster. So I dropped its creator, Ernesto, a message for advice. The response was immediate and his excitement at having a rider on the route – apparently the first – was palpable. It was an excitement that I understood all too well, because I felt the same when I was contacted by the first bikepacker tackling the Off-Road Runner in New Mexico (that frisson of exhilaration: It’s happening! People are coming! And then the self-doubt: I hope they like it!). I immediately felt a great warmth in his emails, as Ernesto helped me tailor-make my trip on the go. I’d pull over in a tiny cafe, drink a shot of espresso, and rattle off an email on my phone with a query. When the reply came – as it always did – I’d adjust my route accordingly, given the time I had left. Ernesto was my virtual guide and I loved having him with me on this solo tour.

I made sure I didn’t take his help for granted, however. I know that route building is a labour of love – the time it takes to research, ride, and write one up transcends any possibilities of real remuneration, let alone the resultant hours spent fielding questions and updating information. Indeed, the driving force behind such endeavours is invariably a noble one: a desire to share a parcel of land on which you live, or have grown to love, for others to enjoy it as much as you do.

Certainly, I recognise the way in which a well-researched ride can elevate a riding experience. While I love to strike my own path and solve my own route-making puzzles – and I won’t deny there’s an undoubted joy in getting lost and finding one’s way – following the breadcrumbs of someone passionate about an area can be especially enlightening, quite aside from the handy nuts and bolts of where to fill a water bottle or which trails are rideable. Ernesto’s enthusiasm for his homeland rubbed off on me. I particularly appreciated the time he took to not just entertain fellow bikepackers, but to try and educate them, lending a deeper appreciation to the area than I might have experienced through happenstance alone.

Besides, as an appreciator of open expanses, it was impossible not to be smitten by such a vast and uninterrupted land, where dirt roads and double track course in every which direction. When I travel, I try not to draw too strong a comparison between one place and another, lest the nuances and peculiarities of each get lost amongst noticing its similarities. But there’s no doubt that there are strong echoes between my surrogate backyard, Northern New Mexico, and Spain’s Parque de la Serrania de Cuenca – a locational doppelganger, albeit a continent apart. Both lie at high elevations and are characterised by often subtle landscapes. Both are often framed by big blue skies. And both are rich in high pastures, faint doubletrack, and herds of wild deer, along with the kind of billiard table-smooth camping that’s the stuff of bikepacking dreams. I’ve written on numerous occasions about my love of New Mexico, so it’s probably no surprise I kind of fell for the Serranía Celtibérica too.

Both also share a very palpable sense of dereliction, even if where gas stations and dollar stores prevail in New Mexico, at least good coffee, fresh bread, and tapas were sometimes to be found in east-central Spain. I say ‘sometimes’ because this is an area with a well-documented depopulation. As I rode, I listened to a BBC podcast I’d been recommended – Empty Spain and the Caravans of Love – that referenced the very places I was passing, as does this article in El País.

Heading deeper into the Montes Universales and east towards the Sierra Albarracin, this high-elevation land became more gently rolling and agricultural. And yet, there was almost no one to be seen, lending it an austere beauty. Instead, the landscape was punctuated by dilapidated farms and ghost-like hamlets, where the few remaining locals prop up community bars, sipping on tiny, ink-black cortados and lamenting the loss of village life. But as romantic as it is to cycle through such sparsely inhabited backcountry, completely bereft of traffic and lost in one’s own thoughts, the closure of schools and businesses means there are few incentives for young families to live in the area, let alone thrive there. Its once vibrant culture is literally dying out – it’s said the Montes Universales now average less than one inhabitant per square kilometre, half that of its Finnish namesake, making it one of the lowest population densities in Europe.

Knowing full well how contradictory it may sound, the irony is that I preferred these empty hamlets to even the fabled town of Albarracín, further along in the route. Albarracín lies above a curve on the Guadalaviar River and is dominated by medieval walls, the remains of a Moorish castle, and a 16th-century cathedral. A steep, rocky, and thrilling descent feeds riders straight into its backstreets. Yet within its tangle of photogenic alleyways and idyllic plazas, it felt so curated that I struggled to relate to it. Perhaps I’m sounding ungrateful for this perfectly preserved nugget of history. I don’t mean to be! If you’re cycling through, be sure to linger and explore, just do so before the car parks fill with vehicles and you have to share the experience with throngs of fellow tourists. Therein lies the dilemma: how to maintain a positive impact on an area, with sustainability, conservation, and manageability in mind.

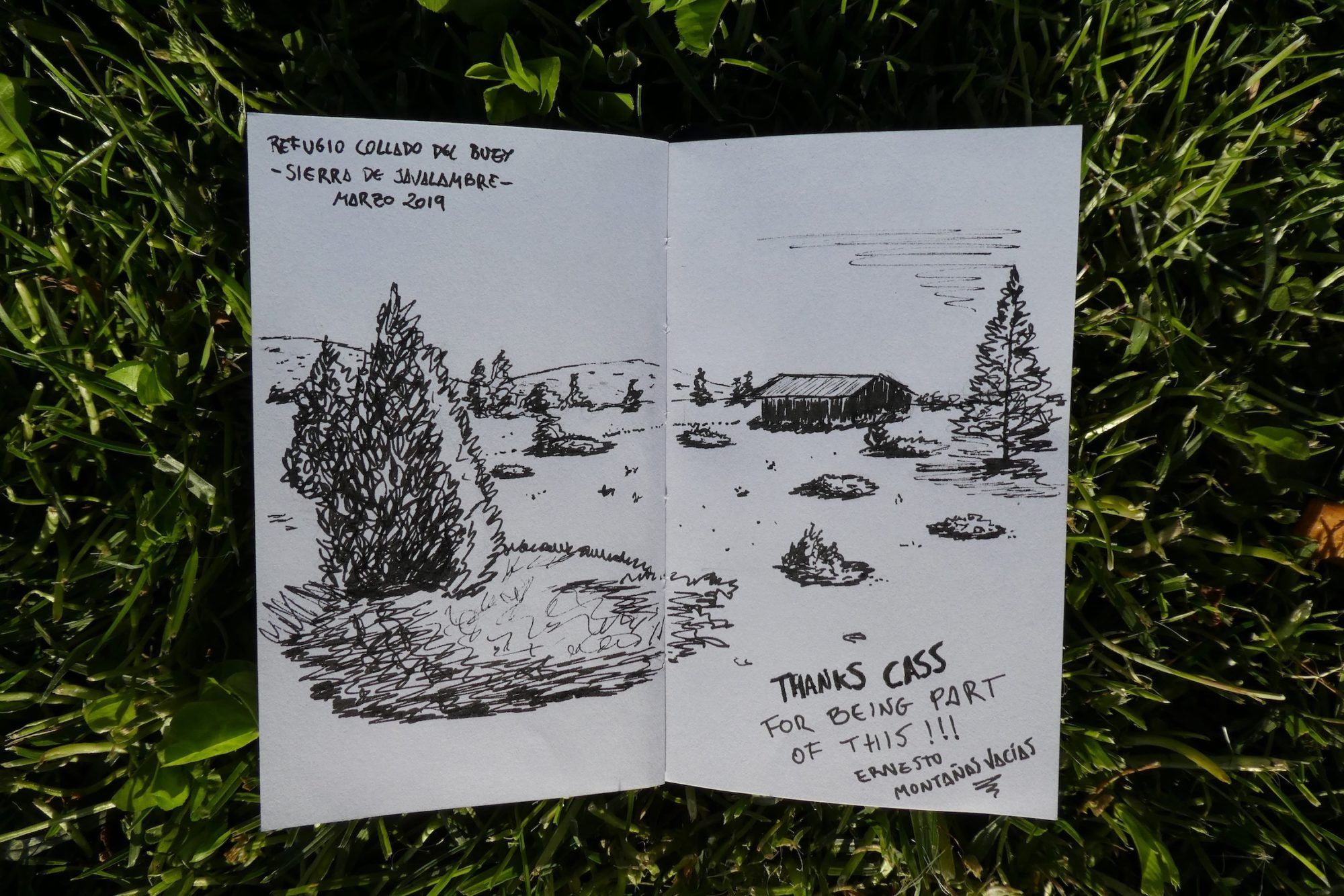

A few days into the ride, Ernesto drove out to meet me – as he emerged from his car, he proffered a jar of peanut butter in one hand and a copy of The Bikepacking Journal in the other. Along with a big smile. He shared his enthusiasm for the miles ahead and primed me with a spot to camp that night. Although he now lives in the larger city of Teruel, where the route starts, Ernesto was born in the area – in Sigüenza – and has thus felt connected to the area and its issues for his whole life. Perhaps it’s for this reason that continues to pour his very being into this project. When he isn’t to be found cycling here – Ernesto has a day job, after all – he’s busy painting intricate maps or making sketches of scenes along the route, one of which arrived in my inbox by the time I was back home. I asked him what lay behind the inspiration to create Montañas Vacías. Was it simply to share an area that’s dear to him with like-minded others? Or a desire to help rejuvenate the local economy?

“The philosophy behind creating this route was a mix of feelings during the year before its eventual “birth.” On one hand, I knew that this area had all the ingredients that we adventurers look for in our destinations: isolation, remoteness, breathtaking landscapes, and thousands of miles of gravel roads with no traffic. During the Torino-Nice Rally I learnt that it clearly deserved to be shared with the bikepacking community. But on the other hand, I wanted to create something – like an experiment – to show that something with no cost or ‘benefit’ could leave a positive impact in a rural area massacred by depopulation. That can be an inspiration to other projects and a stimulus for us to value even more what we have.” Bicycles as both a means of exploration and as a tool for change, then.

Bidding farewell to Ernesto – by now it was dusk, so he drove behind me to help light my way until the next dirt road turnoff – I continued onwards, a willing component in his experiment. For the most part, I rode alone in my thoughts, the road to myself – just as Ernesto had promised. The nights were cold but after winter in the UK, camping felt so very good. At such high elevation, I delighted as much in the crunch of morning frost as the sight of the sun appearing over the treetops and slipping across the meadows. Such a countdown to contentment never gets old.

Not that my every night was spent under a tarp. A series of simple stone huts – carefully catalogued by Ernesto – add further to this area’s appeal. Many have, as he says, “fallen into oblivion and are practically in disuse – before backpackers arrived! Whilst the corresponding town councils are responsible for their maintenance, it’s up to the users like ourselves to ensure that the next visitor finds them in perfect condition.” Some are still pressed into service by the few shepherds who continue to defy the advance of intensive farming, such as 1780m Collado del Buey where I spent my last night. Ernesto’s notes on this particular refugio – part of a self-penned, 30-page guide to the area – painted an appealing picture that rang true: “Basic. The roof is completely new and the interior has been restored. It has a special charm.”

As a steep descent lead me back down to the valley floor and a Via Verde – a family-friendly gravel road – that linked me to a train back to Valencia, where I basked in the glow of such a rewarding ride. I know I didn’t get the full Montañas Vacías experience, at least as Ernesto envisaged it. “I think you rode and tasted the essential sectors of this route – its landscapes, its situations, and its problems,” he later assured me, before letting me know he was working on new route alternatives that he was sure I’d also like.

Don’t worry, Ernesto, I’ll be back. Not just because the Serranía Celtibérica’s sense of space and calm help scratch my New Mexican itch. As much as anything, I’ll be back because Ernesto is a wonderful ambassador for the area and I look forward to enjoying the ongoing fruits of his labour. And in turn, I hope to be a small piece of the jigsaw that helps bring life back to this area.

I rode the first half of the Burrally route – thanks to route maker Luis for hosting me in Valencia – then peeled off onto the Montañas Vacías. Thanks too to Stefan Rohner, another aficionado of this region of Spain, for suggesting a connector and nudging me in eastwards with photos of the grand Cima Javalambra crossing, home to Collado del Buey. I enjoyed combining these two routes – even if it means I now need to return and ride both in their entirety! Expect images from the beautiful Burrally in a future post…

Picture high elevation plateaux, remote refugios, abundant wildlife, and kilometre upon kilometre of quiet forest roads… Welcome to Spanish Lapland, as it’s been dubbed, an area in SE Spain with a population density similar to its Finnish namesake. The 700km Montañas Vacías route offers a wonderful introduction to this little travelled area, linking the Montes Universales, Sierra de Javalambre, and Sierra de Gúdar via a dense network of doubletracks and quiet paved roads. Find the full route guide here.

Picture high elevation plateaux, remote refugios, abundant wildlife, and kilometre upon kilometre of quiet forest roads… Welcome to Spanish Lapland, as it’s been dubbed, an area in SE Spain with a population density similar to its Finnish namesake. The 700km Montañas Vacías route offers a wonderful introduction to this little travelled area, linking the Montes Universales, Sierra de Javalambre, and Sierra de Gúdar via a dense network of doubletracks and quiet paved roads. Find the full route guide here.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.