Armenia in Review

As he closed out a two-month bikepacking trip across Armenia to scout out a potential new ultra-distance race route, Evan Christenson wrote this reflection on how even a 60-day touring pace was far too quick to soak in the country’s unendingly warm hospitality and staggering landscapes. Read it here, along with an extensive gallery of photos…

PUBLISHED Nov 16, 2021

Words and photos by Evan Christenson (@evanchristenson)

Before our last day of riding in Armenia, I had never ridden into a warzone. We were quiet, pensive, and a little tense as we climbed into the same range that served as the battlefront for the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan. It was the final climb of hundreds already ridden in Armenia after some 2,000 kilometers in our two-month assignment, and this punctuation mark was both laborious repetition and terrifyingly exciting.

We clambered into Chakaten, a small hillside town that’s now mostly deserted. Leaves had started to cover the streets and tractors drove stacks of hay from one village to the next. It was gloomy and we were still riding out of the fog—both literal and figurative—that stretched over the mountains and deep into Iran. Three girls, maybe 10 years old, with bows in their hair and wearing backpacks and pink Tik-Tok shirts walked in front of us and cut through the switchback we grinded around. I followed them with my eyes and almost ran into the soldier standing in the road waiting for us.

We waited there for almost half an hour while the officer overseeing the area came over to check us out. He rifled through our passports and took pictures of every page. He walked away and made calls, glancing back at us every few seconds. We stood and waited, eager, nervous, and half hoping he would turn us away. The soldier who stopped us spoke broken English and the others stood around and stared. They were all my age, but I’m certain we’ve lived very different lives until now.

Our time in Armenia served as yet another gut punch reality check. I remember the news from Afghanistan as the US pulled out. I remember my first thought being, “Holy crap, I forgot all about this…” My country had been at war for 20 years and I never once been forced to consider it. But these boys were picked from their families, homes, and jobs and put on the front lines to fight a war they stood no chance of winning. And these soldiers were lucky they made it out alive. One boy came over to inspect my bike, nodding as he moved in closer. We made eye contact and between his anxious glances, I saw my own looking back. He was curious, and in that moment I felt like my own curiosity led us a little too far.

The officer returned and waved us off. He said we can pass through, but we can’t leave this road. This road, the southern highway section on the Armenian Caucasian Crossing, now straddles the Armenia/Azerbaijan border. When we ride through it, we dip into Azeri territory and back out. We ride between warring bunkers five meters apart and see some of the thousands of Russian peacekeeping troops on the roadside. It’s a nerve-wracking final day on the bikes, but after two months in Armenia, hearing stories from the war, meeting soldiers, and seeing the very real consequences of a conflict once so far away we felt curious enough to ride there. We had a friend who rode it a few weeks prior and he said it was one of the weirdest roads he had ever ridden. We were checked again a few kilometers later, and decisively ended our two months of riding with a fast descent into Kapan.

But before that final day, our ride in Armenia was already filled with action. We entered the country excited, and from the first moment we already had experiences that were distinctly, incredibly Armenian. On our first full day of riding, we were passing through Lake Arpi National Park, a small, high-elevation lake near the Georgian and Turkish borders. A Lada 4×4 came flying over the hill, headlights on and a long tail of dust trailing. The car stopped, a bright smile breaking through the yellowing window, and the door opened. The man was proud to say he was the Park Ranger. He made a gesture to come, said coffee, and drove off. Bo and I followed on bike to his home where his wife welcomed us inside. Their small stove in the corner was lit, running off cow patties, and she was making compote.

In the other corner, she fired up her Soviet-era gas stove and made a round of coffee for the four of us. She cleared the table and began piling on different candies and cheeses and fruits and breads. She brought out tea with the coffee and juice and a special Armenian pear soda—pungent and bubbly and sweet like syrup. She made a scramble of eggs from the chickens outside and vegetables from the nearby market and we ate until we couldn’t. And when we tried to say we were full she piled more food onto our plates. And when we ate that, she gave us candy. And when we couldn’t eat that, she grabbed a fist full and stuffed it into Bo’s shirt pocket. We played charades to communicate, toured their home, and washed up in the spring outside. Their house, with its mud walls and dirt floor and Soviet-era furnishing felt just like home on a Thanksgiving afternoon. We were shocked. We heard rumors of Armenian hospitality while preparing for the ride and were overwhelmed by it at the first opportunity. We had been in Armenia for 36 hours and had ridden just 25 kilometers to get there. The entire ride remained ahead.

Armenia is a small landlocked country in the Lesser Caucasus. It’s filled with mountains and canyons and springs and not many people and not much money. Many Armenians have left the country, mainly spurred by the 1915 Armenian Genocide, and now 9 of the 12 million ethnic Armenians are living elsewhere around the world. When we meet people and they ask where I’m from, I would say California, and they would laugh and yell “Glendale! I have cousin in Glendale!” Sometimes we would even get a phone call to a distant relative in France or California or Holland who would translate for someone who brought us in for coffee, a relentless tradition in their culture. We had these experiences dozens of times. Many of our meals were homemade. We had this unbelievable generosity at roadside markets when people would let us sample everything. Sometimes they would reject payment and pat their hearts and smile. We were given walnuts by people picking them from the neighborhood trees. We were given fish from Lake Sevan. We were given coffee at all times of the day. We were given vodka, homemade from grapes and stronger than gasoline, at surprising times of the day. They flick their necks and smile, nodding with excitement and already reaching for the glasses. It’s 10a.m. and we still have another 600 meters to climb, but it’s rude to say no. Nasdrovia!

With its endless dirt roads, interesting historical sites, and beautiful monasteries that pepper the landscape, Armenia feels like it was made for bikepacking. Roads connect everything, and the gravel in the countryside is smooth and dusty and what dreams are made of. We rode most of the Caucasus Crossing, and we also rode our own routes. The similarities between that pristine and well researched route and our hapless, thrown together to get from A to B routes, were astounding. Armenia is full of roads that lead to an interesting town and then goat trails that you can ride out of it. Connecting it all is surprisingly easy, and it feels like whatever path you choose has the potential to show you something incredible. There’s always fresh food and water and someone looking to give you a matnakash (bread) to take along.

I think most of all, and more than most countries I’ve visited, Armenia is best experienced by bike. We saw several tourist busses driving from one monastery to the next, stopping to learn about the truly remarkable timescales and histories some of these buildings have. But I think the magic of the country lies between the must-see landmarks. Bo even stopped going into the monasteries after some point, preferring to wait outside for us to get back on the pedals sooner and see what, or who, was around the corner. What I will take away most from Armenia is not the buildings, but the people who cared about them along the way. They help connect the dots of Armenia’s troubled history. They gave gravity to that story, and drove sympathy into our hearts. Armenia, much more than any iconic figure or church, is best defined by the humanity within its small borders.

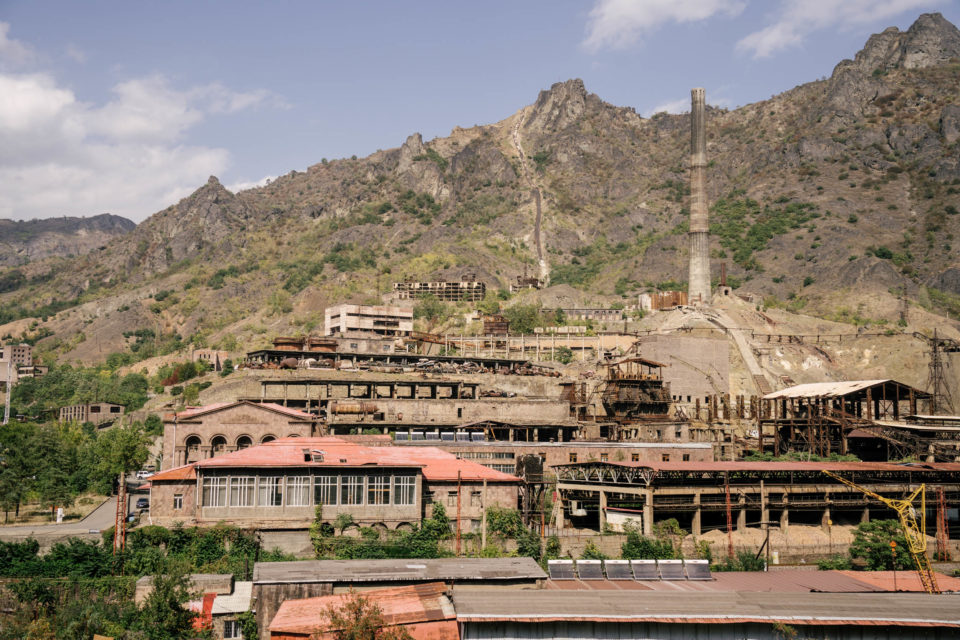

Armenia is not without its troubles, though. It’s filled with reckless drivers and has almost no cycling infrastructure to protect riders from them. It has one bike lane, about 50 meters long, in the entire country. There’s a very small coalition of cyclists and one real bike shop. Today, Armenia still lives in the shadow of the USSR, and the economy has largely failed to modernize and get moving. Except for a small group of uber-wealthy in the capital city, most live with very little. Almost no export industry exists, and 45% of the population lives in poverty. The difference between the countryside, where old Ladas are almost exclusively driven, homes are heated with cow patties, and abandoned buildings roughly equate populated ones, to the city, where Rolls-Royces are driven around fancy shopping malls, is astounding. Hallmarks of corruption abound in these places. Armenia, the world’s 129th economy, has a lot of work to still do, especially after last year’s devastating war.

We went to Armenia looking to flesh out a route for a bikepacking race, but I had doubts as soon as we started. I was enamored with the people of Armenia and the longstanding traditions: the dozens of shepherds high in the mountains excited to give us directions, the old women with headscarves tending to the homes, the soldiers laughing through our exchanges, the friends we made, and the homes we slept in. I thought about how our pace was still too fast for Armenia. How a place like this, with mountains so grand, could take years to explore. Maybe even a lifetime. We had dinner with Tom Allen and his wife Tenny one night. Tom left the UK on a bicycle to tour around the world, but he got to Armenia, fell in love, and never left. He ended his trip there and started building a backpacking route, The Transcaucasian Trail.

Right now, I feel compelled to travel until there’s nowhere new to go. Right now, I want the road. This one and the next. But Tom’s story? In some of those unbelievable moments, the sunsets over Mt. Ararat or that warm home and family barbecue in Kapan, I understood. When we left Armenia, I felt like I could have turned back around and done it again, seeing an entirely new set of incredible landscapes, meeting an entirely new road family, and having even more of those life-altering moments. So, I wondered from the start if it’s a country made to race, or if it’s best left as a country to ride. Because, for me, it’s a country made to slowly fall in love with, one conversation, one photograph, one mountain at a time.

Related Content

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.