Bikepacking Iran: Beyond the Veil

Share This

While bikepacking across Iran last fall, Johan Wahl and his wife Jana peeled back some of the layers of misunderstanding that shroud the country, getting to know its people firsthand while navigating broader political complexities. Find their story finding connection and inspiration accompanied by a vibrant gallery of photos here…

Words and photos by Johan Wahl

Our taxi swerved at a devilish speed around the tight bends of the mountain pass. The driver was undeterred by the cars and motorcycles coming from the busy road ahead. He took daring chances, overtaking other vehicles on completely blind corners, each time coming dangerously close to a head-on collision. There was no cruising speed; only flooring the pedal or slamming the brakes, both done with what felt like aggression and a complete disregard for the road’s geometry. It reminded me of exactly why I dislike road transport. We would’ve preferred to continue pedalling, off-road and at our own pace, but unfortunately, our time had run out. Our first visa was about to expire, and an extension was denied. Once again, we were leaving a country earlier than anticipated with our bikes strapped to the roof of a taxi. The same thing had happened in Armenia a month earlier.

I could have sworn the man was getting a kick out of his reckless driving. When I looked at him through the rearview mirror, I imagined seeing a spiteful smirk on his face. I tried to act cool, as if to be unfazed by his driving, but I was seething inside, and secretly I despised the man, even though I barely knew him. My mind was awash with negative thoughts.The further we went, the more resentful I became.

It was dusk when we finally arrived in Saqqez. The warm light cast a calm veil over the city as if to hide the tension that boiled within its streets. Four weeks earlier, on the same day we entered Iran, Mahsa Amini, a woman from Saqqez, was beaten to death by members of Iran’s religious morality police in Tehran after she was taken in custody for an improper hijab. The incident stirred rage throughout the country and resulted in widespread protests. The police responded violently to the protests, and hundreds of demonstrators were killed. Arriving in Saqqez, the tension was palpable. Even our fast and furious driver seemed oddly subdued once we entered the city.

It would be our last night in Iran. Our bikepacking trip here had been a rollercoaster of ups and downs. It didn’t start smoothly or end as planned, but it was an experience like none other. We had mixed emotions about leaving, but under the circumstances, Iran was not a country where we wanted to risk overstaying our visas.

When we asked to be dropped off at a hotel near the bus station, our driver, whom I had so fiercely resented just minutes earlier, surprised us by offering to host us at his home instead. He showed us an English message on his phone that read: “You come to my home; be my guests.” This time, a friendly smile graced his round face. It took me by complete surprise. In my thoughts, I had belittled the man and based solely on his reckless driving, I had taken him to be a callous brute. I was wrong about him.

Bahman was his name. Despite some apprehension—I was still rattled by the man’s appalling driving—we accepted his invitation. At home, he was a different man altogether, and I had to quickly take back my initial judgement of him. He revealed himself as someone with a gentle and loving nature. His loving attitude towards his wife and daughter was evident in his every gesture and word. He was a gracious host, too, going to lengths to ensure that we were comfortable. We discovered that Bahman and I share a mutual love for photography, and despite the language barrier, our conversation about camera features and technology carried on late into the night. By the time he saw us off at the bus station the next morning, I felt deeply ashamed about my harsh initial feelings towards him.

This was not the only time that I misjudged someone or a situation. Iran continually challenged my initial impressions. It was a recurring theme throughout our ride there, in fact. I was frequently confronted with reminders not to jump to conclusions so easily. Another clear demonstration of misjudgement occurred when we mistakenly entered the country with too little cash. We braced ourselves for potential negative consequences, but to our surprise, the outcome turned out to be quite different.

Due to sanctions against Iran, international payment networks like Visa and Mastercard don’t operate there at present. Tourists must bring their own cash. We knew this and planned accordingly months in advance. Iran was the third country on our tour through the region, and all the other countries on our itinerary—Georgia, Iran, and Türkiye—would accept foreign cards. Accordingly, we packed some hard cash that we reserved solely for Iran—US Dollars and Euros that he hid in various places on and in our bikes to safeguard it until we arrived there. We had most of the cash we thought we needed for our stay in Iran, but we still planned on drawing the last bit from an ATM in Armenia before crossing the border. However, we left Armenia under unexpected circumstances. Mid-route, violent clashes broke out with neighbouring Azerbaijan, and the situation threatened to escalate. We had to make a hasty departure, and in the process, we completely forgot to draw more cash.

When we entered Iran, we were further caught off guard by the unforeseen complexity of its currency. Due to the low value of the rial, the prices of most things are in the hundred thousands, sometimes millions. For example, a cheap soda is about 100,000 rials. To use smaller numbers in day-to-day trade and dialogue, Iranians drop a zero when quoting prices, calling the resulting figures tomans. For example, 100,000 rials would be 10,000 tomans, or confusingly, just 10 tomans as some, but not all, use for short. To make things even more confusing, there are newer bills in circulation that are printed without the final zero. For these bills, you don’t drop a zero to arrive at tomans, even though they’re still called rials and not tomans. It took me more than a month to learn these ins and outs.

Then there’s the exchange rate to decipher. The rate that’s listed online—the official exchange rate—is subsidised by the Iranian government and is used only for unsanctioned imports. By subsidising the official value of the rial for imports, Iranian consumers pay less for the end product. But the real value of the currency, its value on the street, is way less than the official rate, and we didn’t know this. By implication, we were to get much less money out of our cash than we had bargained for.

To make things worse, we got scammed immediately after crossing the border. Between tomans, rials, new bills, old bills, and the massive stacks of money the exchange guy handed me, I completely lost count and walked away with less than half of what I was promised.

When we realised our predicament, Jana began to panic. I thought I’d console her by physically showing her all the foreign cash we still had stashed throughout our belongings. I knew that it wouldn’t change anything, but I thought that the sight of the cash, however insufficient it was, would shift her perspective and somehow cheer her up. We still had money to be thankful for, I thought. It was not the end of the world.

Back when I hid the money, I saved a note on my phone that listed all the places of concealment and the amounts of cash each contained. I now started reading them out, one by one, while Jana had to collect the bounty. “100 Euros in the diary,” I read.

“Yeah. Where else?”

“100 dollars in my seat post,” I continued. “And 250 Euros in the medicine bag, 50 in the…”

“Wait, what?!” she suddenly interrupted.

“250 Euros in the medicine bag,” I repeated. It was our biggest single batch. When I said this, Jana burst out into tears. It turned out that in an attempt to shed some weight from her heavy setup, she had thrown away our medicine bag more than a month earlier, still in Georgia. She’d kept the important meds, but all the rest, mostly packaging, went into a trash can at a public park. She’d completely forgotten that there was still money stashed in between the medicine instruction slips.

I quickly did the maths and realised, with horror, that we now effectively only had enough money for 11 or 12 days in Iran out of the 60 we’d planned for, and this was on an already stretched estimate of daily expenses. I could feel myself edging towards the same state of despair that Jana was in.

It was in this state that we entered the country: genuinely worried that we wouldn’t have enough money to get by on. However—and this is where our expectations had been so misplaced—when we left Iran four weeks later, we’d still not spent half of it. Not even close. The acts of benevolence we encountered were so abundant that we hardly ever had any opportunity to use money. This left me astonished and deeply touched. To have received a meal or lodging now and then is one thing, but the unwavering generosity was so prevalent that in the span of a month, we found ourselves practically unable to spend money, despite our strongest efforts to do so. It’s like money was all but meaningless in the face of the overwhelming kindness we experienced.

What struck me even more was people’s readiness to dispense kindness. There was never a moment’s hesitation. No sooner would someone make eye contact with us than they would already offer a gift or an invitation of some sort. Instead of initiating conversations with customary greetings, people would often cut straight to the chase and call, “Come eat!” or “Stay. Be our guests!” It seemed so instinctive that even small children shared this trait. For my part, I’m usually more calculated in my interactions with others, carefully considering my words and actions to avoid voluntary inconvenience to myself. It astounded me to witness how effortlessly and selflessly people in Iran acted with kindness, and it left a profound impression on me.

Nevertheless, there were also elements of Iranian culture that were difficult to accept, particularly the norms surrounding gender roles. For example, if Jana was a local, she’d never be allowed to tour around on a bicycle like we did. It was only because we were tourists that she was excused. Similarly, while it’s technically legal for women to drive cars in Iran, female drivers are few and far between. Boys of any age can explore and roam the streets freely—the place teems with boys on motorcycles—but you seldom see any young girls out in public. These might seem like shallow examples, but the notion persists through all parts of Iranian society. Even though we expected as much, as Iran’s gender biases are widely known and criticised, we couldn’t help but feel disturbed by it all.

However, what surprised us was the massive disconnect we sensed between people, in general, and the ideologies promoted by the state. We quickly got the impression that the rules and religious guidelines that Iran is infamous for are merely a facade and that beneath the veil was a country whose people were largely open-minded and modern in their thinking. For the most part, we sensed a widespread and a strong discontent with the country’s conservative social norms. In their homes, out of the public’s eyes, many of the families we connected with exhibited a refreshingly modern and progressive approach to family dynamics and gender roles. In contrast, it’s mainly the authorities that still seemed adamant about upholding a conservative social order. Rules are strict, and the consequences for swimming against the stream are dire.

A teenage girl who we befriended towards the end of our stay confided that she identified with the Mahsa Amini movement but felt powerless to express herself. She had once secretly joined a protest gathering, and shortly thereafter, her father received a threat from an anonymous caller who warned him that if he wanted his daughter to continue living, he’d better not let her be seen demonstrating again. It’s disheartening to consider that she is just one among many girls and women in Iran who desire to express themselves yet find their voices suppressed by the pervasive system of intimidation that prevails there.

One of our hosts, an academic, told us what had happened to his colleague, a specialist in conservation ecology. In a clear display of government censorship, he was imprisoned for nothing more than collaborating with international researchers on a study that measured the environmental degradation in parts of Iran.

The internet is censored too, and most social media platforms are completely banned. Moreover, due to the protests, internet restrictions were ramped during our time there, and for a long while, we had no way of contacting anyone outside of Iran. We could still use VPNs at first, but after the protests intensified, the web was completely blocked.

I had to be careful with my camera. Police lashed out at those who were suspected of filming protest activity, and I was cautioned not to take my camera out anywhere near cities. Early in the trip, before I’d been made aware of this, we were strolling in the streets, taking photos in the market when a shopkeeper suddenly urged us into his shop. “Hurry, the police are coming!” he said urgently. He closed the shutters and instructed us to sit low behind a display of Persian carpets. It was a police raid, spurred by rumours of planned demonstrations. We listened anxiously as chaos unfolded in the streets outside. “It’s not safe here for tourists,” said the man.

After that incident, we steered mostly clear of cities. We kept to the countryside, where things were significantly calmer, but it was still a challenging time to be bikepacking in Iran. It was the end of an unusually hot and dry summer. Surface water was scarce, and temperatures were still uncomfortably high. Despite the heat, Jana had to contend with cycling in three layers of long clothing to cover up all her skin. I did mostly the same, but only to avoid standing out, as men generally don’t wear shorts in Iran.

The roads were extremely dusty, but we seldom got to rid ourselves of the dirt. Showering, and personal hygiene in general, seemed an oddly difficult topic to breach. Moreover, public swimming is also frowned upon. In the mountains of Kurdistan, people use irrigation ponds that look just like luxury swimming pools with ice-cold, crystal-clear mountain water. We could die of the temptation of diving right in to cool off and wash ourselves, but inevitably, every time we neared one of these pools, there’d be someone watching us. The hills had eyes!

We attracted a lot of curiosity with our loaded bicycles. We were stopped frequently and had to explain our intentions each time. In this way, our progress was slow. It was difficult to convince the locals that we were cycling on difficult roads out of free will when petrol costs the equivalent of a mere $0.05 USD for a litre there. No one could understand why we didn’t just take a car instead. Needless to say, bicycles are not very popular in Iran, and we stood out like sore thumbs. Everywhere we went, people pitied us.

In spite of these hurdles, the places we managed to reach, especially those far-flung corners of Kurdistan, proved immensely rewarding. The region is extremely mountainous and has an overall raw and untamed feel with rugged mountains and withered vegetation. Yet, within these mountains are wonderfully fertile valleys where small agricultural communities thrive.

In each of the villages and towns we passed through, we were welcomed with open arms, and the locals’ friendly hospitality allowed us to get a clear view into their lives. People were eager to teach us about their traditions and customs. They sang for us, and played beats on the daf, a tambourine-like instrument. They cooked us local delicacies and even took us out to milk the goats with them. We saw the whole process of how butter, cheese, bread, and other local food products were made. Interestingly, butter is churned in a sewed-up goat skin that’s suspended from a wooden tripod. We learned how to operate the samovar in which they brew their tea, and, most crucially, we also learnt enough of the local dialect to request for the strong brew to be diluted with water.

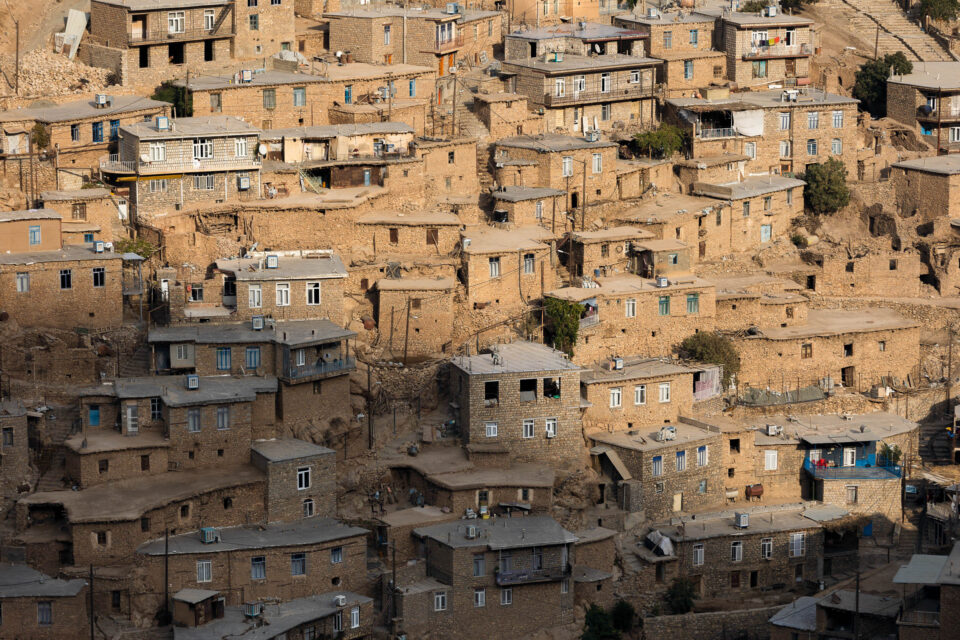

We took great delight in the scenery too. Villages are beautifully constructed with houses built ingeniously into mountain slopes like steps. One house’s roof is the neighbour’s patio. Each village we entered seemed more impressive than the previous, and we would gladly have continued getting to know these places for another month, but we were limited by the time on our visas.

When we returned to a larger city after our final stint in the mountains, we were struck once more by how much the protests had gripped the country. People were now calling it a revolution, and police presence had visibly intensified. Moreover, reports of casualties and arrests were increasing daily. We weren’t sure if it would be wise to stay in the country under the circumstances, but we felt strangely reluctant to leave. Unsure what to do, we decided to apply for visa extensions and let the outcome decide our fate.

As it happened, our application was unsuccessful, and for the second time on our trip, we had to leave a country under less-than-ideal circumstances. It was humbling to realise that both times, the impact of political events we experienced extended well beyond our ride. While we could simply move on to the next country, the people in the places we left behind would likely suffer through great hardship.

Iran is an intriguing place, and it’s frequently misunderstood or disregarded in other parts of the world due to its prevailing negative image. We only rode through two of the country’s more than 50 provinces and probably only got to witness a tiny piece of the vast puzzle that is life in Iran, but what we saw was enough to thoroughly rattle our worldview. Most notably, I was deeply moved by the unparalleled hospitality and overwhelming generosity of the people. It surpassed my expectations of what I thought was humanly possible and raised the bar for who I want to become as a person.

Money was trumped by kindness, and that speaks volumes. I also learnt not to judge too early. With Bahman, I learnt that a person’s character is not defined by a single action or trait. So, too, I believe it’s unfair to judge Iran solely based on the flawed ideologies of its leaders without considering the diverse perspectives of its people. The people of Iran are remarkable in their qualities, and they left a lasting impression on me. I wish them fairness and prosperity.

Do you enjoy our in-depth reviews, route guides, and stories? We’re a small, independent publication dedicated to keeping our content free for everyone, but we need your support. To keep articles like this one coming (and not behind a firewall), please consider becoming a member of our Bikepacking Collective. By joining, you’ll receive The Bikepacking Journal in the mail twice a year, industry discounts, and many other great benefits. Learn more here.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.