Inside Pass and Stow Racks: Beautiful Utility in Oakland

In this Field Trip, photographer Evan Christenson heads to Pass and Stow Racks in Oakland, California, to tour the fascinating space and spend a day with founder and fabricator Matt Feeney. See inside Pass and Stow, peek at some unique prototypes, and learn about the mindset required to hold together an artisan rack manufacturing business and a full-time job as an oncology nurse at the same time here…

PUBLISHED Jun 5, 2023

The city of Oakland exists within a complex duality. On one hand, it’s set in paradise. The redwoods softly peek through the rolling fog banks, the Golden Gate languishes with pride in the distance, the little cafes hum, and the neighborhood gardens chatter. Countless people commute on bikes and everyone seems to wears hip old clothes and compost.

On the other, Oakland is also cars being driven into garages to steal bikes. Shattered glass left on the street. Tent cities and needles and ungodly expensive. Oakland is EV chargers and literal dumpster fires, potholes, and exploded truck tires. The train clatters and bangs across the tracks overhead as I ride into town, and I turn down a small back street as the doors shove open. Matt waves me in quickly, nervously, before the cranky neighbor comes out yelling.

Matt Feeney smiles constantly. A bad story of his always ends with a shrug and a smile. “Oh well.” His mustache blends into his scruffy gray beard, which blends into his wild gray hair. He wears Coke bottle glasses that swell up his soft eyes and overalls atop his old bike T-shirts. We tuck into his shop, I double-lock everything, and he gives me the tour.

We’re in an old metal foundry in Oakland, a former World War II manufacturing space turned heaven for hippie artists looking for cheap and big manufacturing spaces to produce some of the most iconic pieces in American history. Today, the neighbors are all involved with Burning Man in some way. Sound design and art cars or just the big burning man himself. But it’s all art of some sort. Matt points to the lot across the street, its big trailers and bright colors poking through the chain link fence, and he says, “All that over there is for Burning Man. I have no idea what they do, though.”

Most of them are building art installations. The sprawling warehouses and old manufacturing equipment meant this place is where industrial artists could shore up and create their nests. The neighbors built a dragon four years ago, complete with a fire cannon and flapping arms. It cost over a million dollars to make. And Matt’s old neighbor, Don Rich, was famous for his massive copper pieces bigger than a family car. His crucible was just 10 feet away from the back fence they shared. Don died last year, and his place is now a haunting relic of the minds that once worked there. The radio is left on in his honor, and during quiet lulls in the shop, you can hear it rumble away in the distance.

Walking through Matt’s shop is a pressure cooker of creativity too. In the front, it’s another guy doing sound for Burning Man. Next to him is the guy restoring old pianos. Then you squeeze past the furniture maker from Denmark. Then it’s Erik Billings of Billings Cycle Works, the communist philosopher and steel frame builder sat beneath his shelves of old bikes, still filet brazing and building bikes “the old way.” Matt’s shop is behind all this madness. It’s a small shop, kept neat, with a lathe and a CNC and labeled drawers full of all the small parts he needs. We walk in, and Matt takes a deep breath. This is his domicile. I’ve entered his world.

“I’m into being around people that make shit, for sure,” says Matt. I ask if all these creative people around him inspire him in ways or have changed his process. Matt sees himself not as an artist but a craftsman, digging into the challenges of manufacturing. He’s obsessed with quality and investing more time in production, rather than creation. His shop is not elaborate or full of giant copper crucibles, but it churns out great racks one after another. In this small corner of Oakland, he’s found his home.

Erik is in the shop constantly, showing off broken frames and racks he’s been hired to repair. The two spitball together and grumble over cheap foreign bikes and dissect the bad design of a cheap off-the-shelf rack brought in broken at a vent hole. Erik shows me where the flaws all are. Vent holes shouldn’t be put in the heat-affected areas, he grumbles. He pulls out his soapbox. “…it puts us…the artisanal worker…in a difficult position. Because of neoliberal labor practices, this rack costs almost the same to buy new as to pay me to repair it. The real value of the rack is obscured by the… probably two dollars the worker in China or Taiwan was paid to make it. And this engenders an unnecessary culture of throwaway items, masquerading as durable, and supports grossly unjust and exploitative labor practices overseas…”

Matt was born and raised in New York City. He’s a city guy through and through, inspired and excited by the constant happenings around him. When he eventually retires, he just wants to go back to New York and further immerse into the chaos of the city. But, when he was young, he was eager to find something new, so he left New York and headed west. He tried San Diego. He tried Denver. But when he got to San Francisco, he fell in love. “There was just so much going on. You could walk down the street and see… anything.” He knew an old skater friend living in a house, and he moved in. Five kids shared one room, and Matt got a job at a bike shop and started exploring the city he had fallen in love with. The energy was contagious. The possibilities in San Francisco back in the ‘90s were endless.

Matt had already been a bike nerd before moving here. He started riding bikes into the foothills to escape New York as a teenager, and he was a die-hard adopter of the flatland BMX craze. But that, like everything, came and went. “I was listening to Rush on my headphones and doing tricks by myself for like a whole year,” he laughs. Once flatland died out, Matt bought a secondhand Fat Chance mountain bike from a colleague at the bike shop and started riding the trails on Long Island. There were no rules back then. Matt felt freedom.

He was working on his nursing prerequisites at City College in San Francisco, working at a bike shop, and brazing bike frames in his spare time. He taught himself how to braze, and had already made 40-50 bikes then, built under the name M. Feeney Cycles. But he was commuting everyday on the bike and tired of carrying his sweaty backpack to class. There really weren’t many racks to choose from back then, so Matt went home and just made his own. A friend saw it and liked it, and asked for one. Then another friend wanted one. So, Matt went back to the garage, and Pass and Stow was born.

Nowadays, his process is much more refined than holding tubes with his hands and brazing as he goes along. It starts with straight gauge 4130 chromoly steel, trucked in from the port. Matt cuts six at a time with a bandsaw, miters the rails, sands off the burrs, drills the vent and light holes, bends the bed from one tube, drops it all into the fixture, brazes together the legs and beds and the add ons, sands it down, gets them powder coated down the street, tacks on the head badge, and uses the magnifying glass for quality control. In a good day he can make up to six or seven.

Pass and Stow Racks Archive

Matt’s racks have undoubtedly changed over the years, and in the 20-odd years and 2,000 or so racks he has made, he’s learned a few things. I asked him to walk me through some of the fun ones. Here’s a teaser of what will someday be his rack museum.

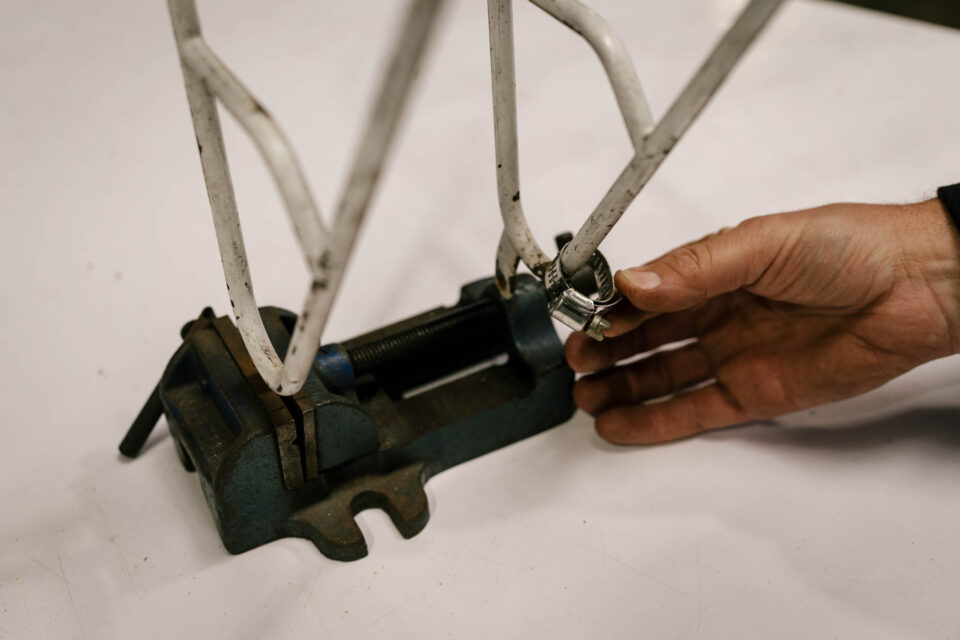

Rack #1

This is the first one Matt ever made. It’s brazed together and then powder coated. The hard-mounted wide struts made the rack super stiff, and the little rails jutting out the bottom were to hold straps. “But that didn’t work too well,” Matt said. The hose clamp is there to go around his skewer to protect the wheel from being stolen.

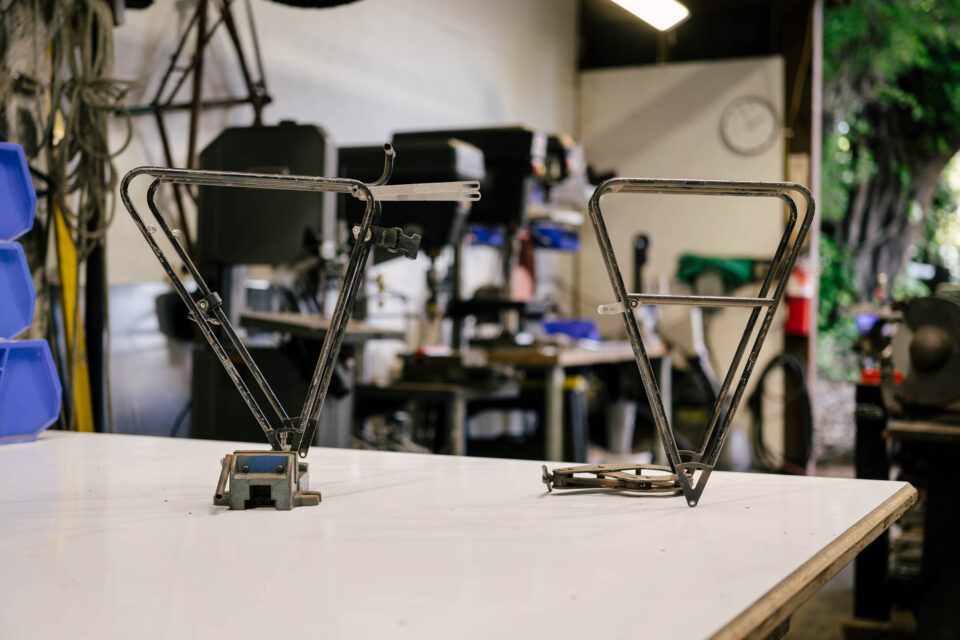

Rack(s) #2

These touring racks were made as one-offs to go with the touring bike Matt also made for a tour down the Pacific Coast. They have integrated “lift the dot” straps, which are military spec and super weird to use.

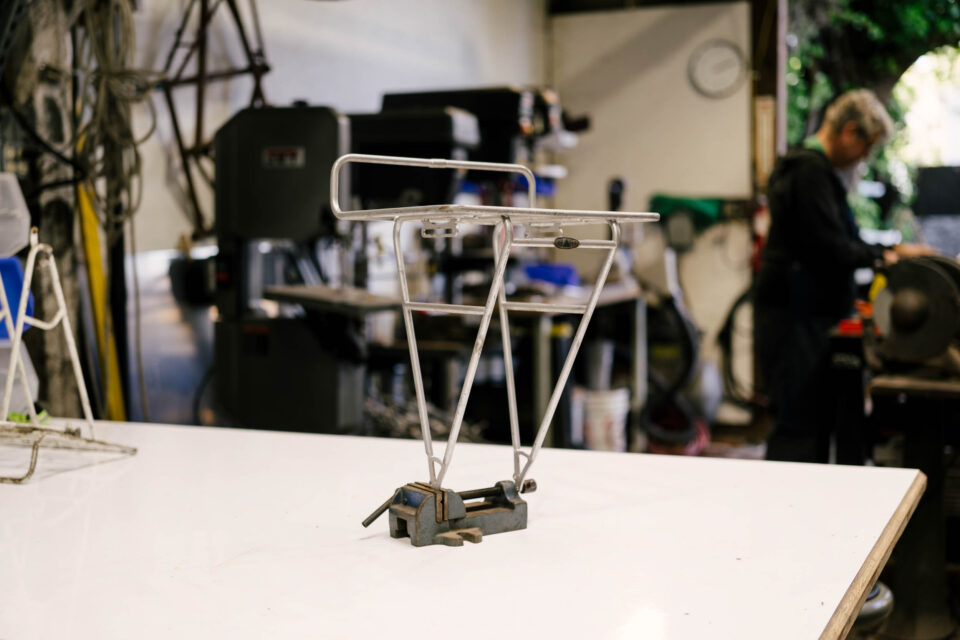

Rack #3

This is an early prototype of a minimalist rack, just two straight supports and a small bed. This one was easily my favorite. I asked what year it’s from, and Matt just shrugged, adding, “Who knows.”

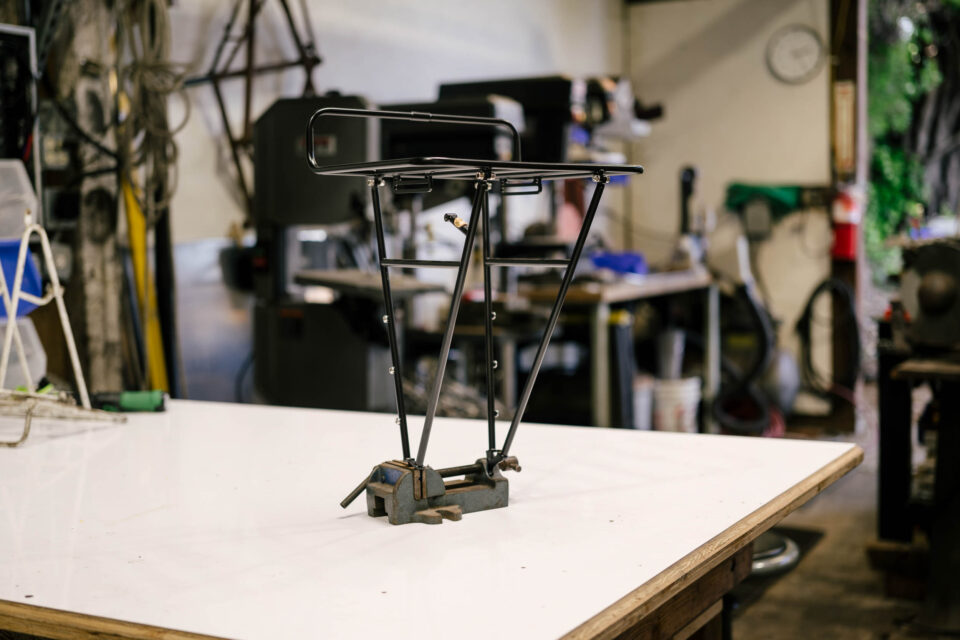

Rack #4

This is a later prototype, before the widespread adoption of cargo cages. It’s meant to go over the wheel and then have stuff sacks strapped to the sides. I said it looks very art-deco, and Matt responded, “Oh, stop before I start blushing.”

Rack #5

This is rack #100, with with the number stamped into the legs. Matt made this one for his wife when they first started dating, and she would commute with it every day. She later upgraded to a newer one that’s better suited to her side-pull brakes. Spot the old head badge too, cast out of brass from an old neighbor who made special trumpet parts.

Rack #6

This is the modern Five Rail rack, which is for sale now on the web shop. It’s collapsible and comes with internal dynamo routing, a light post, hooded dropouts for more clearance, braze-ons for cargo cages, and custom leg lengths (if desired). It has clearance for 29 x 3” tires, and it also has the shiny new head badge, made in Maryland out of bronze.

Rack #7

This is the Three Rail version of the same rack above. It’s been made for seven or so years by now. When I asked how much weight it can hold, Matt said, “I’ve had 160 pound people on these things all the time! How much can your eyelets hold is the better question.”

Rack Dad Life

Matt puts away the racks and leaves the shop to go pick up his daughter from school. He’s stressed out having me around, managing the family, and putting in his time for his other job at the same time. “Rack dad life,” as he calls it. Matt went on that tour down the California coast with his friend Dylan 10 years ago, and afterward, Dylan started nursing school. Matt was looking for an exit from the bike shop spiral, and decided to enroll with him. Now he works as a nurse in an oncology ward in a hospital half the week administering chemotherapy. He spends the other half in the shop building racks. He’s finally brought on help in the past few months. Erik helps with some of the brazing, and Stevie was recently trained in on how to braze. Matt’s now focused on herding the cats and thinking on streamlining his manufacturing process.

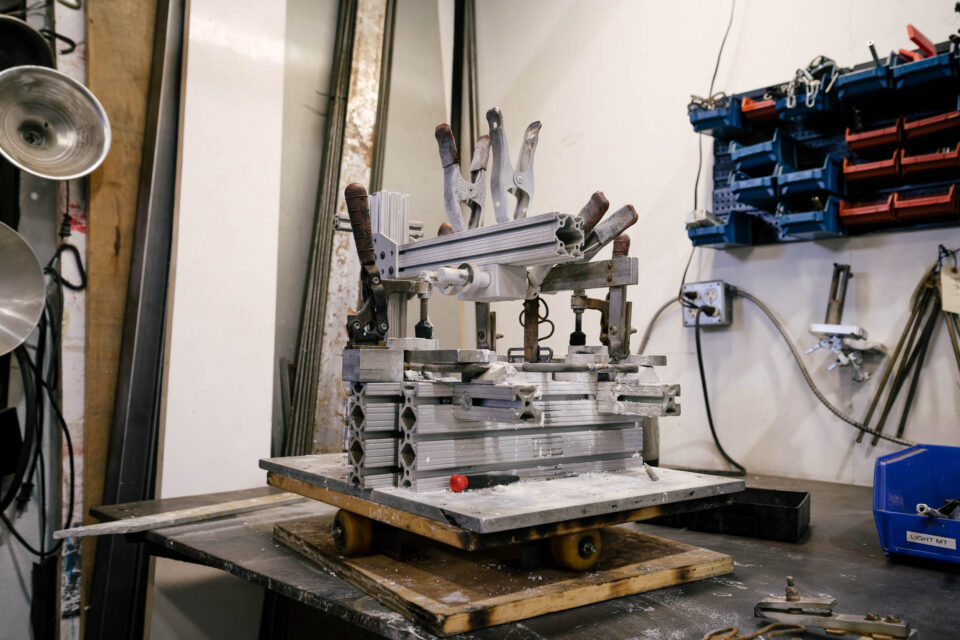

For Matt, so much of rack building nowadays is designing new fixtures, templates, and tools to make these bulky, intricate things easier to reproduce. The old fixtures are made using springs from a discarded mattress, and it rotates on a bed of old skateboard wheels. Matt’s picked up a CNC machine and learned how to use it “slowly” in the hopes it will help lower costs and get more racks out into the world. What used to take him eight hours to hand cut and miter 60 tubes has gotten down to an hour and a half of passive time using the CNC. He thinks there’s more to knock off, too.

Matt is a fun guy to follow around. He knows a lot of people in his neighborhood, and they’re always dropping by his garage to say hey or riding by in the other bike lane waving. He lives on a heavily commuted road, and he says he sits and watches people ride by some days, and he laughs when he recognizes one of his racks on a bike going by, the owner blissfully unaware of its creator on the sidelines. Matt is a city cat, and his racks are made in the city. They’re beautifully utilitarian. I ask him if he see’s them as strictly for commuters. People have ridden them around the world too, he told me, adding, “I don’t like to pigeonhole my stuff.”

The name Pass and Stow comes from the album Pass and Stow by Lungfish, a 90s punk band from Baltimore, Maryland. Further back, it’s also derived from John Pass and John Stow, the two guys who came together to re-cast the bell for the Pennsylvania State House back in the 18th century. The first creators of the bell did a bad job, and no one liked the sound of it. And then it cracked.

Pass and Stow were commissioned to melt the bell down and recast it. Their first attempt was also hated by the townspeople for its lackluster sound. Their second attempt? Well, that’s the infamous Liberty Bell, with the infamous crack that’s made it such a fitting symbol for American democracy. “Is that kind of a bad omen?” I ask Matt, and he laughs again with a shrug. “Oh, I like it! Nothing’s perfect, ya know?” And I wonder. Maybe it is a perfect name for a rack company.

Into The Hills

Matt loads his bike onto the rack on his car and we head out into the hills for a little getaway. I’m eager to see the trails he rides, and hope to understand a bit more of the draw he feels to the East Bay in doing so. Matt asks me if I feel the same pull, and after a couple days of riding around it, I’m hesitant to say I don’t. But, after only a 10-minute drive, we’re above the city in Joaquin Miller park and riding under great redwood trees watching the ocean as it laces its humbling fingers through the city. Joaquin Miller connects to the broader East Bay Regional Park system, the biggest urban regional park district in the country. We ride through sweeping singletrack and dodge the river jump and climb quiet, technical, beautiful trails higher and higher. The climb tapers out, and we stumble into the shade to chat.

The climb to this spot hasn’t been that long, but the road before it seems to have endlessly dragged on—Matt’s journey to this point in his life, wrangling two jobs, building a brand, and caring for the family. It’s been hard. Matt’s father died when he was 16. He was a firefighter in New York and died of lung cancer. And now, while working in the oncology unit, Matt confronts that same pain every day, and staring our fragility in the face. “It weighs on me, for sure,” he says, taking a drink from his bottle, sweat soaked into his high-vis cycling cap. “I know there’s no difference between me and the person I’m treating in the chair. The next day, it could be me.” Matt takes a pause and looks around. This is his place to recharge. Riding bikes is his escape. It always has been, and he’s confident it always will be.

Matt doubles down, looking back a bit more. “With the childhood I had, I’m genuinely shocked I’m here right now.” Matt looks at himself, healthy and in shape, with his bike at his side and his racks just an arm’s length away. We talk under the canopy at the horse ring in the park. His daughter Frances rides up here on her mountain bike nowadays. Matt glows with pride as he shows me the rocky pitch she can finally clean. I met her and was amazed by her poise and intelligence. Matt’s a proud father.

Things are good right now, and we take a moment to appreciate that. The city bustles below, it’s rats nests tangling, it’s dumpsters smoking. We get back on our bikes and pedal into the hills, giddy on our rigid bikes as we ride over rock drops and through rivers. We pause again over the city for one last deep breath. There’s still more recharging to be done. But then again, there always will be.

You can more about Pass and Stow’s growing range of handbuilt racks over at PassandStowRacks.com and find updates from Matt on Instagram.

Related Content

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.