Three Dutch Bike Shops + Their Owners and Bike Collections

In this piece, Evan Christenson continues his recumbentpacking tour around the Netherlands, this time stopping by three unique bike shops. Read on for his impressions of Just Pedal, Wheelrunner, and Studio ROOK, featuring immersive photo galleries, interviews, and a look at each owner’s personal bike collection…

PUBLISHED Nov 1, 2023

In the country of bicycles, there are, of course, some wacky bike shops to check out. What would the Netherlands be without them? Last summer, my partner bought a new Surly, and she sent photos of the tires being swapped out at the shop, which happened to be on a farm in the countryside next to a barn full of horses. Naturally, I was curious about the whole thing. I’ve known one of the shop owners for years now, both circling the same groups, and I have always been amazed by his racing experience and the small shop it’s funneled into. And the last shop has all the while had this edgy, tasteful, mysterious presence online.

I was curious about the three shops that follow, and I figured they would all fit nicely into the same story. I’d later learn that they were all run by remarkably different people using, owning, and selling bikes in three distinct ways. I sat on my recumbent and pedaled into the countryside to check them out. I got rained on a lot. We talked over Dutch food. It was fun. Allow me to present, three Dutch bike shops, their owners, and their bike collections below.

Jelle Tienstra

Just Pedal, Amersfoort link

Bikes are everywhere out here. Like rats in New York, they’re scattered abandoned in alleyways, they’re thrown dead into canals, and they pile into traffic. Bike highways, bike traffic, bike garages. For the Dutch, it’s born out of utility, the small country and close proximity to everything, the flat cities. Everyone talks all day long about the infrastructure. A step-through bike with a basket for a run to the shops, a red bike lane in the forest, mom riding with the baby carrier on the front, and two little kids giggling away.

There are tracks in the Netherlands built specifically for bike racing, like small car-racing tracks, with corners and grandstands and a finish line. This is Jelle’s start: growing up in a rural Dutch village across the street from one of these things, a parcours, as they call it, and hanging around after school watching the racers and their bikes whizz by from his front yard. Jelle has always been a bike guy, a technical nerd, interested in all things mechanical. A tinkerer by heart. And so, at first, it was the bikes that got him. A history of Jelle and cycling, to him, is a history of his bikes. He first bought a Giant Cold Rock, an old rigid mountain bike, inspired by the road racers just across the street. He laughs about it, “It was the bikes I liked, not the road!”

Jelle went off to college and studied agricultural engineering. He has a master’s degree in it, not that you would know. He talks firmly and directly with his thick Dutch accent and smiles heartily. Beads of sweat roll down his face after a long day of wrenching in the heat. We sit in his grassy courtyard, and the smell of last night’s rain and the buckets and fields of horse poop hang thick in the air. He crinkles a packet of Dutch cookies. Gingerbread, I believe, and Coke to wash it down. I ask him about his degree. He takes a gulp of his Coke and crinkles more gingerbread. “Ahh who cares! Who cares that I have a master’s? That’s the good thing about cycling, we meet a lot of people because of it. They’re anything. Unemployed people, doctors, people who do the tooth thing [meaning dentists]. I have a master’s and own a bike shop… Who cares?”

Jelle went and worked in IT after graduating in agricultural engineering, working for 20 years in project management, mostly with Heineken, the Amsterdam-based beer juggernaut. But, in the meantime, he had fallen deep into a rabbit hole. He started riding single-speeds in college. He had an old steel Gazelle hybrid, and after destroying the drivetrain, he converted it over. Singlespeed sort of just makes better sense here in the Netherlands. The mucky winter trails, the student budget, the 12 meters of climbing for every 100 kilometers of trail. In university, they were early adopters of the internet and of email, and he quickly found an online community of people all focused on singlespeeds.

He bought the URL singlespeed.nl and took photos of his friend’s bike shop to show to Surly, faking he had a shop to buy himself parts that were hard to source in the Netherlands. And, gradually he began to resell them online. The business slowly grew, always a side hustle, and for 16 years, he ran the webshop, moving into his own space, selling and racing and riding all the while. He’s a regular at Singlespeed Worlds, at local underground cross races, the guy “first into the bar and the last out,” he jokes, and he tells stories of the early day alleycats at NAHBS back in its heyday. He seems to know everyone.

When the pandemic and the associated bike boom hit, his online shop took off. Now named Just Pedal and selling a broader range of parts, he left his job in IT and focused on the shop. They had just moved into his wife’s family’s countryside house, which was built in 1892 and ran for a hundred years as a farm. He set up in the garage, storing parts in the attic and bikes in the barn, and he works from home now, letting the horses out in the morning and giving his kids a cookie when they return from school.

Jelle likes his balance and has no plans for growth. He’s already maxed out on space, and the Dutch government won’t let them build more buildings on the property. He focuses on steel bikes and was an early adopter of Singular. He’s also the only Dutch dealer listed on Surly’s website and is now fully legit. That long-standing gray area relationship gave him a hand up in becoming the only Dutch Surly shop, and now that’s become the bulk of his sales. He ships them all over Europe to customers trying to get their hands on the otherwise hard-to-source culty steel iconoclast bikes.

Jelle gave me a tour of his lengthy bike collection. Surely a perk of the job and a symptom of his mechanical obsession are his bikes, but he guaranteed me they’re all regularly ridden, rotated, and maintained. They all had air in the tires, for what it’s worth. Find a swipeable gallery of each with captions below:

Jelle lets me camp in the garden. His wife makes pancakes for dinner, and we chat over beers in the garden. Hot air balloons dot the sky, the horses trot in the field, kids giggle and play down the street. The tinge of manure still hangs over the property, light rain scatters the ground, and lightning strikes on the horizon. The reed roof on the farmhouse shakes in the wind, the light grows soft, the couch sinks deep. We tell stories from days on the road, from races and tours and the rides where everything goes wrong. Jelle is busy now with the shop but still regularly getting after it with his friends. Chain lube runs through his blood, and bikes define his community. “That’s why I started a bike shop,” he says. “Because everyone I’ve met through cycling is good.”

I leave full and happy in the morning. Jelle sees me off, and I finish my tour around the Netherlands. Jelle gives the ligfiets a try, but despite decades on a bike, he can’t ride the recumbent.

Bas Rotgans

Wheelrunner, Amsterdamlink

Bas started Wheelrunner four years ago as a way to get out from behind his computer. He was working in marketing, focusing on sports and events, mostly for Red Bull, the rest freelance. In his apartment is a photo from working on the first scouting missions when the Red Bull cliff diving series was still in its infancy. A man is stretched out, diving off a centuries-old arch into a surging emerald river. He looks a hundred feet up, a mere blip in space.

There are trees and granite, a building that looks to be a cathedral, and stabbing rays from the sun. The man wears a small black thong. His arms are stretched wide, and his head is thrown back. He hurtles through the air into a world below with grace and poise. The photo is eternal youth. It is eager and joyful defiance. It is the bold impossibility of our imperfect species, arms stretched out, head back, stomach in throat, and flying for no reason other than a brief glimpse of perfection. It sits above his oven. The glass is dusty. We quickly move on. For Bas, leaving all that behind and starting Wheelrunner, it was yet another plunge.

I pedal down a side street in De Pijp to get to the shop, the old and buzzing neighborhood crammed with ancient apartments and schoolhouses, a sandwich of prosperity, daycare centers in the middle, and edgy squatters cafes on the side. At the end of the street, sex workers set up shop in small, red-lit windows across from mossy canal boats. We’re mere blocks away from the main tourist neighborhoods of Amsterdam, although you rarely see them here. Tourists act like slot cars from afar. Walk, selfie, eat, selfie, the weed shop, the Red Light District, Van Gogh, back to bed, back to home.

The bike shop is small, nestled in between apartments, below apartments, across from more apartments. Walking in, it even feels like an apartment, white-walled, the shoulder-hunching bathroom, the posters tacked on the wall. I think how maybe it is just an apartment for someone really obsessed with bikes. The shop has no showroom space; most of it is reserved for the mechanics, and that’s really where Wheelrunner shines. They don’t sell bikes straight out of a box, built from someone else’s parts list to someone else’s needs. Bas specializes in custom builds. Gravel bikes are all the rage in the Netherlands, and bikes from Bas all come decked out with only the best, his favorite stuff. “I just feel like that’s the best way to build a bike,” he says. And if the customers are willing to pay the price, it’s a claim few would disagree with.

Wheelrunner is a lovely space, comfortable, if a little tight, like everything in Amsterdam. Bikepacking bags dot the walls, and quality products are for sale. Nothing extraneous. Nothing too flashy, either. But with its snug space and utilitarian parts, it’s become the de facto bikepacking-friendly shop in Amsterdam. The stuff hanging on the walls makes it nice, but the real value in the shop is the trove of knowledge on the other side of the bench.

Bas has raced some of the hardest bike events in the world, almost always coming out on the other side, always learning, always piecing together and refining his own builds, always hacking them back to life in the most remote corners of the world. For the bikepacking-curious staring down the barrel of their first ultra, or even their first overnighter, it’s worth more than any shop rate. What Wheelrunner specializes in, really, is knowledge.

“I’m not really from anywhere. That question doesn’t register with me,” says Bas as we get in the car. We’re heading for his home in Haarlem so I can see the rest of his bike collection. The traffic bustles and clogs through the slurry of bike lanes, raised and crossing and spilling out into the roadways. Driving through Amsterdam is hell for a cyclist. It’s slow, it’s confusing, it’s obviously stupid, and so much worse. Driving in Amsterdam is watching the cyclists go faster and have more fun with their kids laughing upfront and their perfectly conditioned hair flying about and feeling the familiar sharp pain of FOMO as the clutch pedal squeaks and the car sputters away from another red light and rattles over the train tracks and a delivery moped cuts you off while carrying hot food you’ll never get to eat. I hate driving here. But driving we do because Bas has multiple bikes he has to transport tonight, including my stupid recumbent strapped on the roof.

Bas’ dad worked in dredging. Dredging, sand, dams, harbors, water, and water bending is the specialty of the Dutch—the people from the land that was once the sea. They’re hired as contractors all over the world, and so Bas and his family left early and hopped around. From the Netherlands to South Africa to Nigeria to Germany and back to South Africa. Bas enjoyed it, enjoyed the excitement of new places, but later they returned, and he finally found a home back in Haarlem, the suburb of Amsterdam he’s recently come back to.

He went to college there, and it was there he met a friend running a company organizing outdoor excursions for company retreats. They needed help, and so Bas was brought on as a guide before he knew any of the activities. He was given lessons in archery and canoeing and orienteering and finally mountain biking. He was given a bike to ride, and he sputters away from another red light and says straight ahead, “And it grabbed me by the balls like nothing else,” as if that’s not a slightly disturbing image to tell to a stranger. The next day, he bought a used Specialized Rockhopper for 500 gilders and fell into a deep relationship with the sport, taking it to the Alps early on to find the limits of rigid bikes with small tires in big mountains. He broke two collarbones in three months.

Bas kept riding, finding his way into the head editing position at a Dutch mountain bike magazine, and started racing enduro bikes. He says it was the first time he trained for something, and his body responded well. It was the early days of Strava, and they had just announced the Festive 500. He gave it a go, cycling 500 kilometers in five days for the first time. But it was miserable. Rain and cold and no time for holiday fun. So, for the whole next year, he wondered if it was possible to do it again but all in one go. So he bought a drop-bar bike and planned it, and the following year, he took a train to Paris with three friends and rode home. It rained almost the whole time. He burned 13,000 calories. He was hooked.

Bas has since done Paris-Brest-Paris, the Silk Road Mountain Race, the Atlas Mountain Race, the Bohemian Border Bash, the Further Pyrenees race, Cabin Fever, the Hellenic Mountain Race, the Highland Trail 550, and probably some more he can’t even remember. Most of these were on his old Salsa Cutthroat (which is for sale if you don’t believe in carbon fatigue and are looking for a good deal), but I still had him show me through his bike collection. Find them in the captioned gallery below:

I asked Bas what he likes about ultra races. He says they help him cut through the noise of life. They give him a target to fixate on. Be there, this day, at this time, and then do only this one thing. Bikes have always been this complex avenue for fun, weekend trips to the dunes, and races in the Alps. Fixies and beach cruisers and the like. Enduro racing was, to him, like a bike vacation but faster. But ultra-racing is more than that. It heightens the consequences of it all, the drama. The noise is louder and but the knife is sharper. “It’s like a pressure cooker… I feel like I do well in that.”

Bas has certainly done well, and Wheelrunner is undoubtedly a testament to that. But he also couldn’t ride the recumbent.

Rokus Wilmink

Studio ROOK, Rotterdamlink

Rotterdam is a gray city full of sharp angles and dense clouds. It was razed flat during the bombings of WWII, and the Dutch, in retaliation, have built a haven for experimental architecture. The city is not tall but wide, round in design, and piercing in shape. It feels disorganized, excited, half avant-garde, half Willy Wonka. Rotterdam as a city bumbles along, still feeling its way into its new identity. “People don’t stay here long, so they don’t put much into it,” says Rokus. He will cut the dying sunflower in his front yard and bring it home to his girlfriend. She will tear it apart and roast the seeds. They will eat them together.

I wobble along wobbly sidewalk bricks down a quiet and sleepy street on the waterfront. Freighters move idly by, great yellow cranes sleep high in the sky with their massive industrial heads kinked aside. Rotterdam has the largest port in all of Europe, and right across from it, I find my destination.

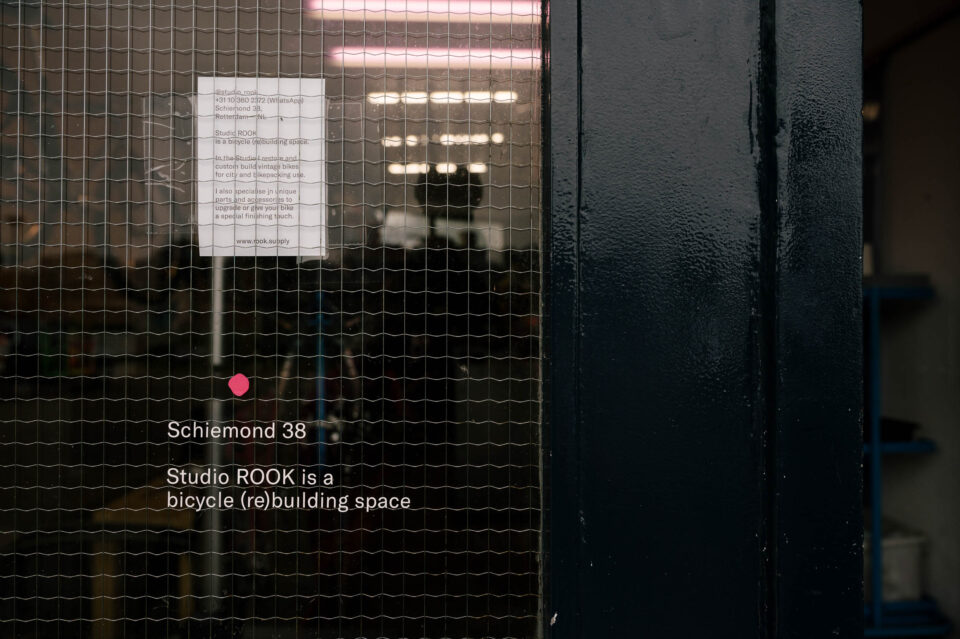

Studio ROOK blends into the surrounding walls. It’s unassuming. Purple lights and big purple letters suggest something else, but the passersby, bumbling along the waterfront on their Sunday afternoons, look inside, say “Oh, nice bikes,” and continue to bumble on. Rokus and I get fries with mayonnaise; he goes for the vegan one, and we sit and talk. I immediately learn this isn’t a normal bike shop.

Rokus started a bike shop nine years ago in the center of Rotterdam. He had gone to art school and entered the adult world, working graphic design at a big firm. He immediately didn’t like it. The structure, the competition, the creative farming never appealed to him. He had started with bikes only a few years prior. His grandfather passed down a bike in his will to him. It was an old Batavus city bike, made before WWII, and Rokus started riding it. But he never took care of it. He rode it and beat it up and let it sit in the rain. The brakes broke, and Rokus laughs a bit as he remembers riding into a bus because he couldn’t stop in time.

One day, he decided he could change that. He watched YouTube videos, read articles from Sheldon Brown, picked up a wrench, and started experimenting. He fixed his bike, and with his aesthetic training from art school, made it look a bit nicer. White-wall tires, aggressive chrome handlebars, singlespeed. A “cafe racer,” as he calls it. The bike rode well, stopped finally, and he was off to the races, so to speak.

Vintage has such an allure nowadays. We crane and swoon and yearn for better days when everything was new, exciting, and fresh. Mountain bikes in the 80s weren’t made better to sell another new year’s model. They were made because there was nothing else that could do that job and take you down a mountain without having to walk the whole time. Rokus yearns for the days when Kranked came out, when we didn’t, or couldn’t, fight in the comment section over rim brakes vs. disc brakes, when we were all just stoked to ride because it was this wild new thing that one guy from high school did and maybe we should try it out.

Maybe it’s rose-colored hindsight, and maybe those fights existed in parking lots instead of comment sections. But it seems back in the early days, the whole point was to explore a new, radical idea. Riding bikes down mountains. Or in the Netherlands, just riding bikes out of the city and off the bike paths.

Rokus is soft-spoken, sarcastic. He says after working as a mechanic for so long has made him bitter. He says people would characterize him as pessimistic, but personally, he thinks it’s more just realistic. Rokus has no interest in new bikes. His old space in downtown was focused on rebuilding and reselling vintage road bikes. He’s never sold a new bike in his life. But that space bummed him out too much. People came in demanding lower prices and newer things. The floor had a nice shine, the walls were freshly stuccoed, and he had a large mezzanine. It was too good for someone trying to fight the global forces of consumerism.

He moved to a small garage, cut his open hours to just 12 a week, put most of his business online, and made a huge mess in the back. He prefers it this way. We sit by the water and watch the Sunday walkers bumble through. He takes a long pause. “If I sit here all day and do nothing, nothing happens. I like that.” In this city, the language of creativity is still open to interpretation. Rokus says he likes being in a smaller city because he feels like he can make an impact and change the way things are seen and done.

He charges a lot for his bikes. Around 1,000 to 1,800 euros for a fixed-up old mountain bike. But he does this so that people see that they’re valuable. To him, to the world, to themselves. Undeniably, they’re still good bikes, if only just a little old. He says his customers have already accepted it. He thinks he’s changed the way they see these old bikes.

Rokus looks at me after my tour and our long conversation and asks what I think. I reply, “I feel like you don’t want to sell bikes.” And he smirks, nods, and agrees. “I always say I would give them away if I could. There are two bikes for every Dutch person, and they’re all junk. People don’t know what a good bike is like. They normally don’t smile when they ride here… so when I see someone ride a good bike for the first time and smile, I feel good.”

Before I came here and met Rokus, I plainly assumed he would have an interesting bike collection. I felt it would be a good conclusion to this three-part story. But my stop with Rokus was far from what I expected. I figured we’d poke around his shed of bikes, all old and quirky, fun and bizarre, a pile of wheels and tires and old riding gear. But in his personal life, Rokus hates stuff. His apartment is small and uncluttered, just a couple of self-made tables and shelves, a no-nonsense book collection, some posters. And his personal needs from bikes are small, too.

He goes bikepacking a little, he rides around, goes shopping, rides the muddy Dutch trails, and comes home. Nothing too outlandish. So, Rokus has only one working bike. And for some reason, this feels like rebellion. After nine years running shops, seeing hundreds of bikes come into his doors and go out, he’s held on to almost none. Just this steel 1993 Koga Miyata singlespeed, ceramic rim brakes, big tires, and an old crust rack. It rides nicely. It’s smooth and unassuming. It goes well when you pedal it. The lock goes in the framebag. Some snacks, too. That is all. He mocks my disappointment. “Why would I need anything more?”

I take the train back to Amsterdam. I can’t stand the recumbent anymore, and Rokus doesn’t get a chance to make a fool out of himself on it. We hug each other goodbye, and he pedals off comfortably on his old bike, riding slowly and assuredly through the Willy Wonka streets of Rotterdam.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.