The (Traka) Adventure?

Following his ride of the Traka Adventure in Spain despite its official cancelation due to extreme weather earlier this month, Stephen Fitzgerald from Rodeo Labs penned this ambitious reflection on his history with “adventure” as a racer and organizer. Equal parts insightful, captivating, and revealing, this is an expansive piece you won’t want to miss. Read it here…

PUBLISHED May 13, 2024

I rode my first of eight Unbounds in 2015. Way back then, the idea of riding my bike for 200 miles was a bit of absurdity. It was all so exotic sounding. But before 200 miles came 20 miles. I remember my first 20-mile bike ride, at least three decades ago, very clearly. Back then, for me, riding 20 miles was about as preposterous as 200 miles is today. Once we had done that distance—a few friends and I—20 miles was no longer so preposterous. Months later, we rode 40 miles. Big ups. We were going places.

Reading stories of Unbound, then called DK200, in 2015, made it sound so incredibly exotic. Someone in my riding crew had the idea to give it a go, so at once, we all had the idea to do so together. We hit the Information Superhighway. We searched up some blogs. Tales of woe abounded. The winner one year had badly screwed up his hydration, became delirious, and ended up miles and miles off course repeatedly. Yet he still maintained his lead and claimed the win. That’s how spread out that race was back in the day. Dozens of lost souls spread out across the Kansas prairie like seeds in the wind. Everything was so wide open, so raw, so unscripted.

The first year I participated in Unbound, was the infamous Mud Year, for those who know the history. I awoke that morning to a torrent of rain outside of the Emporia University dorms. For sure, we weren’t going to race in rain this intense, were we? I looked at my friends as they put their jackets on and walked out into it. If they were going to give it a go, I was coming too. That’s what squads are good for: positive peer pressure.

A lot of that race was awful. Such was the mud, such was the cow shit. So inundated was the course for certain stretches that we marched only on foot, dragging our bikes with wheels unturning, for miles. Our shoes collected massive lumps of clay and defied lifting. The mud and grit were so thick that they stuck to my frame, and the accumulation gnawed like a dull blade through my tire sidewall until dismembered. It pissed its sealant into a puddle. I quit the race right then and there. Or rather, in my head, I quit the race. In reality, I was stuck out on the prairie with no cell phone signal and no means of extraction. There was nowhere to quit to, so I kept going. Eventually, the mud bogs faded behind me, and the ground firmed up. Momentum increased. Unexpectedly, I crossed the finish line later that evening. What day. What horrors. What a test. Oh… here it comes: What an adventure. I was hooked.

The second time I went to Kansas, the very next year, I could see that things had grown. There was more buzz. There was more energy. It was more organized. A zeitgeist was forming, like a hurricane, over the warm waters of the Gulf of Gravel. With that influx of energy came more brands, more sponsors, and more money. You could see it happening right in front of you: This gravel thing, this adventure thing, it was all going to be A Big Thing. Everyone was going to want a piece of it. It was still raw, but it was being discovered. It was being monetized. It couldn’t stay hidden even if it wanted to.

Years passed. Adventure, The Thing, continued up and to the right. In many ways, I hopped on and proceeded right along with it, going back to Kansas over and over, looking for that feeling I’d experienced the first year. Sometimes, I found something similar, but of course, there can only ever really be one first time doing anything, so although the challenge continued to be there, I felt stagnation. I became more aware of larger and larger events popping up on my radar. The Tour Divide was definitely well-established by then. The Silk Road Mountain Race had a mind-boggling first go, and I, like many, was glued to liquid crystal dots on my screen creeping across the landscape of Kyrgyzstan at the speed of geologic time.

The bar of what people are willing to do on bikes just keeps being pushed higher and higher all the time. These races, expeditions, and excursions are more and more imaginative and audacious. They’re also inspiring. I was incredibly inspired but incredibly terrified of what it meant to cross a country or continent for not hours but days and weeks at a time. Two hundred miles was too small to cause a wince anymore, but 2,500 miles across Kyrgyzstan was too rich for my blood.

A new race popped up: the Atlas Mountain Race in Morocco. For an ultra-distance event, it was “short” at around 1,150 kilometers. I don’t know why, but for me, that sounded maybe doable. Sure, it was genuinely terrifying. I could simply think about registering and get goosebumps. Eventually, I did register, late, and without even telling my wife. God, I was so terrified. Morocco, Africa, the Atlas Mountains. Alone. I thought a lot about maybe dying out there, which in retrospect sounds dramatic, but imagine it as a bikepacking newbie like me. What If I rode up a mountain and a blizzard hit and got cold? So cold that I had to stop. What if while stopped, snow piling up around me, I just didn’t have the willpower to get moving again? What if everything got warm, and I just wanted to sleep?

Snap out of it, Stephen!

I would jerk awake at my desk at work. I was lost in another daydream about the race. As soon as I signed up for the Atlas Mountain Race, it consumed all of my spare mental energy in the three-month run-up. Outwardly, I was fairly engaged because I had to be—or I had to appear to be so. But on the inside, my mind was in chaos. I was going to ride my bike in Morocco. Alone. This feeling, you can’t bottle it. You have to go out and get it. It’s a rare earth element, more precious than any jewel. This feeling is that of deciding to do something where you are not in control, and you don’t know what is going to happen, and it could go badly, but you’re going to do it anyway. You can’t synthesize this feeling; there is no stevia extract from this feeling. Once you’ve tasted the real thing, you’re quite possibly ruined.

It turns out I didn’t die in Morocco. No snow fell, or rain, or anything really. I got lucky. But even without the elements to endure, that experience took me to Mars emotionally. For five days, I rode my bike alone, with minimal human contact or camaraderie, through the most desolate crust of the earth I’ve ever seen. I’ve ridden in the desert plenty, but the Moroccan desert is so austere that it makes the Utah desert feel like the Garden of Eden. On the third evening of that race, I saw a ground squirrel on a high pass. The sight of it was so startling that I cried.

You can’t live on a mountaintop forever, and after Morocco, I came back down to the valleys for four years. I was so affected by the effort of my singular ultra that I couldn’t bring myself to participate in another one. I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything, but I still genuinely don’t know if I have the mind that it takes to do another. Post-traumatic stress is a thing, and this whole genuine adventure thing can be traumatizing. Even if I paused my relationship with ultra racing, the sport itself most certainly wasn’t on pause. Just like Unbound, its tiny cousin, it has continued up and to the right like a rocket ship. Why? Because Adventure with a capital A is inspiring. People out there doing the thing are incredible to watch, and when we watch, we ask ourselves, “Can I do that too?” Because of this, it seems that the number of ultra-endurance races around the world has absolutely taken off like cells dividing under a microscope in fast forward.

This reality hit me with extra impact a couple of years back when, lo-and-behold, I was planning on hosting an ultra race myself and with my dad in Armenia. It’s a long story on how we got there, but instead of participating in another race, for whatever reason, it seemed like a pretty decent idea to go ahead and host one instead, so we did. If you think riding 200 miles is challenging or 2,000 miles is terrifying, please allow me to propose the next level of oblivion: Invite a few dozen people from around the world to a country few people can find on a map, and have a competition to see who can traverse the squiggly line you’ve drawn on the map the fastest. I really had no idea what an earthquake I was in for. Racing 1,000 kilometers through Morocco was child’s play compared to this.

For the next week, I was, for all intents and purposes, the responsible party for 30-some-odd souls, and there would be no rest at all until every one of them was safe and accounted for at the end. Staring at a Trackleaders map full of dots can be quite entertaining if you are a spectator, but when you’re a race director, every one of those dots is your responsibility, even if they’ve signed a symbolic waiver and purchased some form of emergency SOS extraction insurance. Our race, Ascend Armenia, was not a large race. We had 30 participants in year one. The Silk Road, AMR, Tour Divide, Stagecoach 400, and Transcontinental races can have hundreds of participants.

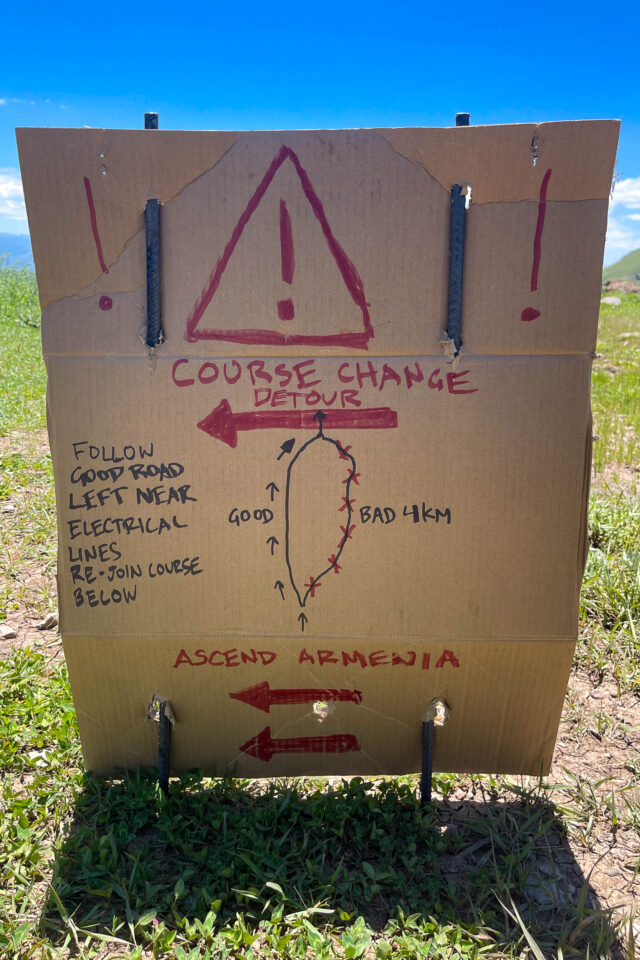

Things didn’t go all that smoothly in our race in Armenia. We had very thoroughly scouted the entire course over more than two years, but here’s a funny thing: We’d done so more in the late summer than the early spring. We then decided to move the event from late summer to late spring, when the mountain snow would be melting. I wanted to show off Armenia’s beauty, and she wears it so well in the spring. However, the course in the spring was not the same course as it would have been a few months later. Tall spring grasses sprung up out of mountain snowfields. Shepherds’ camps and their scary dogs shifted positions of their flocks. Mountain weather patterns were less predictable, which is saying a lot because the weather in Armenia could hardly be described as predictable on the best of days. Regardless, on June 26, 2023, an incredible group of intrepid racers sped out of Yerevan and into the true unknown, into true Adventure—that thing that we all profess to be looking for but so rarely actually find.

Things got rough out there pretty quickly. A number of racers didn’t even make it up the first mountain pass before quitting due to steepness, altitude, and ruggedness. Once at the top and starting down the other side, where August had delivered beautiful sheep tracks and farm roads, June delivered waist-high grasses that entirely erased the route. Firm, dry ground was instead very un-firm, un-dry, and definitely not rideable as we had promised racers that most of the course would be. Empty shepherds’ camps we noted in late summer were now freshly occupied for spring grazing. With the shepherds came the vicious dogs that antagonized and terrorized racers. All this, and it was only the first 24 hours of the race, one projected to last up to a week.

There are carefully laid plans that work, and there are carefully laid plans that, what the hell, nothing goes to plan. Our ultra race was that. As the roster of racers still racing thinned out, I grew profoundly depressed. This is not the experience I wanted people to be having. I wanted them to encounter this amazing country in all its beauty, not be buried under an avalanche of adversity. Unfortunately, adversity was on the menu. Really strong riders, world-class riders, abandoned the race simply because they weren’t having fun. Other riders abandoned because of more serious concerns like trench foot. A few riders at the pointy end of the race tormented me with WhatsApp messages of bogs and tall grass fields and asked me, “Is there supposed to be a track here?”

On the third or fourth night, we drove along the track through the Armenian highlands into ever-worsening weather. A vicious storm gathered, rain pelted down, winds blew, thunder bellowed, and lightning menaced amid the cloud canopy. The situation was not good. Some of the fastest racers had already punched through this section of the course, but mid-pack riders were just summiting a 5,500-foot climb only to be greeted by this present tempest. I can still see the image so clearly: First, Lorenzo Baccifava, a racer from Italy sped by on a soaking, muddy, rocky descent. He did not slow down at all and instead shouted in a beautiful Italian-tinged accent, “You are crazy, man!” I took this as a personal indictment of my race director abilities.

Miles later, the storm worsened, and a rider named Peter Olah rode into view. The rain was horizontal, and yes there was lightning, although not striking from what I could tell. I was ready to force him into the car, which I was sure he would want to retreat to. He was externally soaked, a wet dog, but was wearing full rain slicks. I could see his tired face under his hood. I could feel compassion and concern for him.

“How are you?” I asked.

“I’m okay,” he replied, surprisingly.

“Do you need anything?”

“No. I will continue.”

Shock. I was absolutely shocked. Continue? In this violent storm? WHO WOULD DO THAT? As it turns out, Peter would, and Peter did. I thought about pulling him into the car for his own safety, but I paused. Even though I was the race director, I didn’t feel that it was my call to make for him. Peter said he was okay. Peter had experience. Peter had functional gear, and Peter wanted to keep going. Peter wanted Adventure. At that, we parted ways. I had to just let go of the sense of control I had over him. I was not here to curate his experience. Not able to entirely ignore my deep concern, I advised him that these hills were dotted with farms and shepherds’ tents. Indeed, I had spotted shepherds tending their flocks all day long. If the storm worsened, he was to seek refuge by any means necessary.

For the rest of that night, I followed Peter’s and Lorenzo’s dots obsessively. When they both stopped on the track with no real signs of a building or civilization on satellite view, the deepest sense of dread would punch me in the gut. I messaged each of them on WhatsApp again. After an agonizing wait, they both eventually replied with the best news in the world: They’d been taken in by separate shepherds and were enjoying hot tea and the warmest mountain hospitality imaginable. Most importantly, they were safe.

I almost cried in relief. With more than half the racers now dropped out of the race, each person still in it was so important to me. It was impossible not to care as much as I did. On one level, I was supposed to be a somewhat indifferent race director. But as a human, I just didn’t know how to not care.

For the three or four more days until the race ended, these scenarios repeated over and over for me with different racers on different mountains in different storms. Adrien Leichti’s dot stopped for at least an hour for no apparent reason near a spot on the map for which the contour lines indicated a large cliff. My imagination went wild. Adrien had gone off course and fallen off a cliff, his body broken hundreds of feet below in an inaccessible ravine. I dispatched a control car to this remote part of the course to search for him. What had we done? Why had I ever decided to host a race at all? I’m a terrible human. Minutes later, my WhatsApp lit up:

“I was just having a nap with some cows,” said Adrien. He was completely fine, and the views were great up there.

Later that evening, Tom Quirk summited that same mountain, but a storm cell so powerful that it was colored purple on radar decimated that peak. Tom’s dot stopped, and so did my heart. Not long after, a message with stories of hospitable shepherds and homemade vodka once again lit up my phone screen. The kids were fine. Tom was fine. Adventure is quite often fine.

Less than 30 percent of the people who signed up for Ascend Armenia finished the race. In my mind, I deeply feared that it was all a failure. Dogs, trench foot, spring bogs, thunderstorms, and bikes destroyed by mud. It was all too much, just way too much. Certain participants would surely agree. But a funny thing happened: Many of the racers who finished—and those who didn’t finish and stuck around for the final party—told me that win, lose, or scratch, it had been a beautiful experience. A true adventure.

I think about this a lot: My definition of adventure compared to the definitions of others. What was the number that encapsulated the experience that made me feel like I was touching the live wire of adventure? At first, mine was 20 miles, then 40, then 200, then 1,150 kilometers, and then it was all too much, and I had to step away. For others, it seems there is no limit. For some, it’s 2,000 or 4,000 kilometers. Continents can’t contain them, and in some ways, for them, the adventure never stops.

At the beginning of this month, I found myself staring out of the window of a perfectly curated third-wave coffee shop in Girona, Spain. Outside, an unspeakable drought had been mercilessly draining regional reservoirs and swimming pools for the past few years, only to finally be interrupted by a week of generous precipitation. This rain was suspiciously timed on the very eve of a race I was attending as my foray back into all things “ultra.” Enough years have passed that I needed to check in on my adventure PTSD. Was I still a burnt fuse after Morocco? Were exhaustion and anxiety still too much for me to stare directly in the face? Or maybe I’d processed it all enough to get back in the saddle. I hoped so. I really love this sport, except for sometimes when I’m actually doing it and it’s too hard.

The Traka Adventure is a new distance for a relatively new-ish event on the endurance gravel calendar. It’s been building momentum for a few years now with the 360-kilometer (200-mile) distance, and this year announced a new 560-kilometer (350-mile) length, one that I’ve deemed for myself the “nano ultra,” which is an oxymoron if there ever was one. I’ve been looking for a way to dip my toes back in the water of doing hard stuff again without the threat of drowning, and the Traka Adventure seemed just the bill.

Hosted in one of cycling’s current hotspots of Girona, Spain, the Traka boasts attendance by the absolute who’s who in the gravel cycling scene. It is, for all intents and purposes, the European equivalent of Unbound, arguably the biggest gravel event in the world. Sparkly stuff, to be sure. With the new 560-kilometer distance, the Traka had garnered the attendance of top ultra athletes, most of whom were excited to be there and a few of whom weren’t but had to be there because sponsors strongly suggested they make an appearance at the Met Gala of bikes.

Instead of going at this new thing solo, I asked my good friend Nick to participate in a duo team with me. Also along was Cade, who works for me as a lead engineer, and Luke Hall, an accomplished racer at this distance, who I invited because, dammit, I’m a sponsor of bike racers too, and I thought it would be awesome to see him race with other top-flight athletes.

As primed as we were to launch into the sort-of-scary unknown the next day, fate had other plans. The constant rain in the lowlands had brought with them fresh snow along the race course higher in the Pyrenees. Discussion in the race participant chat channel began to speculate with chatter of re-routes. This seemed unlikely to me, if not unthinkable. Was this not the Traka Adventure? Does not the very word imply the unexpected, and the very name invite it? Surely, a couple dozen kilometers of high mountain snow wouldn’t be dangerous, would it? Is this not the industry that will sell us gear for every scenario? Do we or do we not have miracle puff jackets and waterproof membranes that somehow keep outside water from getting inside while simultaneously letting inside water freely out?

Chatter increased, and those who spoke up publicly seemed increasingly concerned about (their) safety. Then, the news from the organizers arrived: The course would be altered out of the mountains and below the snow line. Thirty percent of the elevation gain of the race would be calved off in the process, and with it, 30 percent of the adventure. I was selfishly bothered by this development but took it in stride. This event would still be no walk in the park, and the forecast for the race days continued to be grim. My crew and I continued packing our bikes and filling bottles for the next morning’s departure. We finished up and ambled down into Girona’s tourist-filled streets in search of gelato. As I watched my scoop of goodness ball up in my waffle cone, Cade appeared with an announcement:

“What’s your emotional state right now? Can you handle some news?”

“I’m fine,” I said. “Hit me.”

“The race is canceled,” he replied.

I went into shock. Wait, what? Why? Yeah, I mean, it was raining cats and dogs, and I was pretty stressed out about being drenched for at least 30 hours while out racing, but I had prepared for four months for this race and had spent thousands of dollars registering and flying my crew out to do the thing. How could they just cancel the thing like that?

The organizers sent out an email and a video. They were very genuine and apologetic. The weather was intense, there were forecasts of thunderstorms along the route, and the situation wasn’t going to improve enough to safely host the event. Since signing up for the event, in all communication from the race staff, one word had been emphasized more than any others: Safety. I think these people really genuinely wanted to keep all of the racers safe. Every decision flowed down from that singular goal. But I also didn’t get it.

What exactly was unsafe? The rain? The mild temperatures? The possibility of thunderstorms? What exactly does “safe” even mean in bike sports? Literally every single time I throw a leg over my bike and ride to work Monday through Friday, I have to make peace with myself that bikes rate pretty low in terms of safety, and anyone reading this has borne the weight of tragedy that impacts our cycling community on a regular basis. So, what is safe, then? Perhaps safe is not safe at all but merely less dangerous on a sliding scale. To an athlete, maybe their personal feeling of safety can be quite high, but an event organizer who is loaded with the weight of hundreds of people can be bent to their limit under the strain of responsibility.

I did a quick flashback to Armenia and the storms that had struck me with terror. I guess I could relate to the need for caution by the organizer, but those unsafe memories of mine were of remote areas in a far-off land, and the region of Catalunya that the Traka passes through can be scarcely described as remote. I thought also about my most recent Unbound in 2023, with yet again miles of soul-destroying mud and yet another thunderstorm I rode through for 45 minutes, torrential rain soaking me, lightning flashing above me, with nowhere to hide. I was nowhere near safe in that moment, and neither was anyone else in the vicinity, but no harm befell anyone. The Unbound organizers hadn’t called that event off, and I couldn’t imagine them doing so short of an impending tornado.

Is Unbound unsafe? Or what about something like Tour Divide? I wonder what conditions they would cancel that event for? Forest fires, probably, but rain, snow, and hail? Definitely not. Some of the best stories from that event are racers either squeaking over high passes being pummeled by snow, or retreating back down the mountain back to the next town, only to try to get over again the next day. But then again, in 2022, racers had to be plucked from the course in droves by search and rescue for those very same reasons. That feels unsafe, but the racers in that situation were left to decide, and the organizer didn’t intervene. The Hellenic Mountain race in 2023 looked like a march through hell in my eyes, with near nonstop rain and a course that literally had to be cut through a snow field by organizers for racer safety. Few people finished that one! Were they safe?

I couldn’t make sense of it all, and it wasn’t my call to make. There would be no Traka Adventure. Life deals the cards, and you play the hand you are dealt. We sat in a stupor in Plaza De Independencia in Girona for a few minutes and processed our disappointment out loud. Then someone, I don’t know who, finally said it:

“We’re here, we’re experienced, and we have good gear. Let’s do the Traka anyway.” It was agreed on unanimously and instantly. A familiar sensation ripped through me: A pang of excitement, anxiety, fear, and anticipation. I could tell that we were about to have that thing I had come here for: A genuine adventure.

We returned to our base camp apartment, finished packing a few more things on our bikes, and went to bed early. We would wake up at 3 a.m. and shoot to be riding by 4 a.m. None of us really slept more than an hour. Outside, a tempest raged. Rain inundated roofs and alleys around us. Thunder rumbled overhead. Lightning lit up even the closed and shuttered windows. As I lay in bed awake, not knowing that everyone else was also in bed awake, I felt the return of that feeling I knew and hated so much: That post-traumatic stress of my adventures of yore. There is no way around it; nights just get dark for me.

As I wrestled with my thoughts, my mind grasped for the exit. I wanted to bail. I wanted to abandon before I started. The thought of willfully riding out into that dark and stormy night triggered every emotional response I could think of, and I couldn’t hold back all the waves. Was this whole ultra thing just self-harm? Was this masochism? Maybe by some definitions, it was, but by others, this was what I had come to Spain for: adventure. In order to access that thing, I needed to face my fears and find out if I was capable of overcoming them anymore. If I wasn’t, a diminished life and sense of self is what waited for me somberly on the other side of this trip.

We rode into the storm right at 4 a.m. It was wet and dark and cold, and I was scared. But I was on some sort of autopilot. I just had to turn that crank over once, and then again, and then again, and keep doing it. That tiny halo of headlight beams from our four-person group was all that fought back all of the outside forces that attempted to paralyze me, so I focused on that.

The dark sensations subsided with each passing minute. For the next 100 or so miles, every minute of our ride became more and more sublime. Familiarity took over, and its embrace was warm. I had done things like this before, and I could do things like this again. Up and over hills and mountains we rode. Through stunning valleys carpeted in heavy fog and tiny towns shuttered and bundled against the night. The glow of the sun soon came, and with it that incredible hope of a day about to be maximally lived. Moods soared. We flew. If what we were doing was dangerous, it was dangerously beautiful.

Everything went swimmingly until lunchtime the next day. Just as the forecast predicted, heavy dark afternoon clouds once again built up overhead, and our Traka route plunged us directly into them. Rain began lightly and then turned heavy. The roads and puddles, already still wet from previous storms, filled quickly. Conditions truly went off a cliff in the span of 15 minutes. Soon, we were riding through a tempest.

I began spotting rain that bounced, which could mean only one thing: hail. With the hail came the sound of thunder, and with the thunder lightning. The delays between the thunder and the lightning were approximately zero, which meant the thunderstorm cell was directly overhead. Cade wisely made the call: we needed to seek any shelter we could find. We found a sparingly small tin roof that protected a series of mailboxes-turned-birds nests from nothing at all, and we all huddled together underneath it. Overhead, the sky was violent.

Five, 10, 15, 30 minutes we stood there. The storm barely moved at all. We were all quite wet and began to shiver. We weren’t well protected where we were. I decided to look for a better building or shelter. There were farms all about, and a barn would be ideal. Instead, we found a freestanding electrical closet that at least had three walls and took refuge inside. Shivering increased, and out came emergency blankets. Another 30 minutes passed. We shivered, keeping an eye on each other and communicating about how we were doing. It was all very uncomfortable, but nobody panicked.

The storm that moved so slowly eventually passed, and we set our sights on a sustained climb not long ahead on which we knew we could warm up. Within 10 minutes of ascending, we were reheated and shedding layers. The crisis had passed, and all was well once again. The higher we went, the more signs of hail there were until, at the top of the ridge, we were shocked to see at least six inches (20 centimeters) of accumulated hail covering the road. I’ve never seen that much hail piled up! Had we been 20 or 30 minutes down the road, we surely would have been caught by the storm on that ridge, pounded by hail, and possibly also hunted by even more aggressive lightning. The thought was sobering to us all.

Back down into the valleys around Girona, the next 100 kilometers of the course was an extended series of flat and flooded farm tracks and dirt roads. Where some roads had been now waited extended flooded lakes, streams, and temporary rivers in their place. The water was often as high as half our wheels. The entire rest of that day was an absolute slog, and our progress was laughably slow.

I thought back to the race organizers and the call that they had decided to make. If you had asked me if the race should have been canceled at 12 p.m., I would have said that it was a near foolish miscalculation to do so. But now, at 4 p.m., slogging through rivers of muck seasoned with cow poo, I could see the relative wisdom of the organizers’ decision.

It struck me that when it comes to adventure, there is no binary set of principles, is there? Is it ever truly black and white? Is it ever not absolutely relative? What is good and right and even fun for one person is never going to be the same for the next person at any given starting line.

Were those racers safe in the mountains of Armenia last year? How about the people who raced Smoke ‘n’ Fire 400 through thick wildfire smoke? How about people snatched out of blizzards in the Tour Divide? Would all 250 racers have been safe on course had the Traka Adventure gone ahead? No way. I had noticed too many inexperienced people asking very beginner questions in the group chat. Sure, Lael and Sofiane and Quinda and Ulrich would have been safe in the snow in the high Pyrennes, but the people just dabbling in ultra-distance challenges could have been totally caught out in very dark situations. Were we safe in the lightning and hail? I felt like we were. Were we miserable there for a bit also? Yes, definitely that too.

In 2024, it feels to me that the word “adventure” is like salt that no longer seasons. It’s so used up, so over-promised, so dangled in front of us. I fear that a lot of times, we wouldn’t know it if it hit us in the face. And if adventure did hit us in the face, would we call it dangerous because we could be injured by it? But at the same time, we’re all coming at these bike sports with varying sets of abilities and expectations. I myself started small, worked up incrementally to something really big in Morocco, and then had to retreat from that experience for years. When I hosted the race in Armenia, I put on an event that was far too difficult for some but almost unremarkable for others.

This very website posted a simple question to the community at the very moment that we were out riding the Traka Adventure course: Should events be canceled due to weather? Or better yet, as an Instagram meme page more poignantly put it: Should an adventure event be canceled because of danger of actual adventure? I laughed out loud when the irony of that one hit me. Adventure, indeed!

Our Traka adventure ended beautifully. After the heavy rains of the day passed, we sought shelter that night to dry off and rest for a couple of hours, then continued riding again at 1 a.m. Overhead, the night sky dazzled with crystal clear skies shimmering with stars. The second daybreak in the hills overlooking the ocean on the Costa Brava was one of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen. Our small band of riders soaked up the incredible challenge of the course, battled our personal doubts and demons, and prevailed upon the finish line just before sundown that second night.

This incredible sport that we have the privilege of participating in is made up of a spectrum of beautiful humans who have infinitely different goals, styles, and abilities. If I compare myself with the giants of ultra racing, I will come up far short and feel that my tolerance for true adventure is somehow lacking. But I think comparing is a trap, and we have to respect our differences as not only riders but also those event promoters whose care we place ourselves in.

I can neither celebrate my achievements as awesome nor decry others’ decisions as not enough. Adventure is what you make it, and we should encourage each other to find it for ourselves.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.