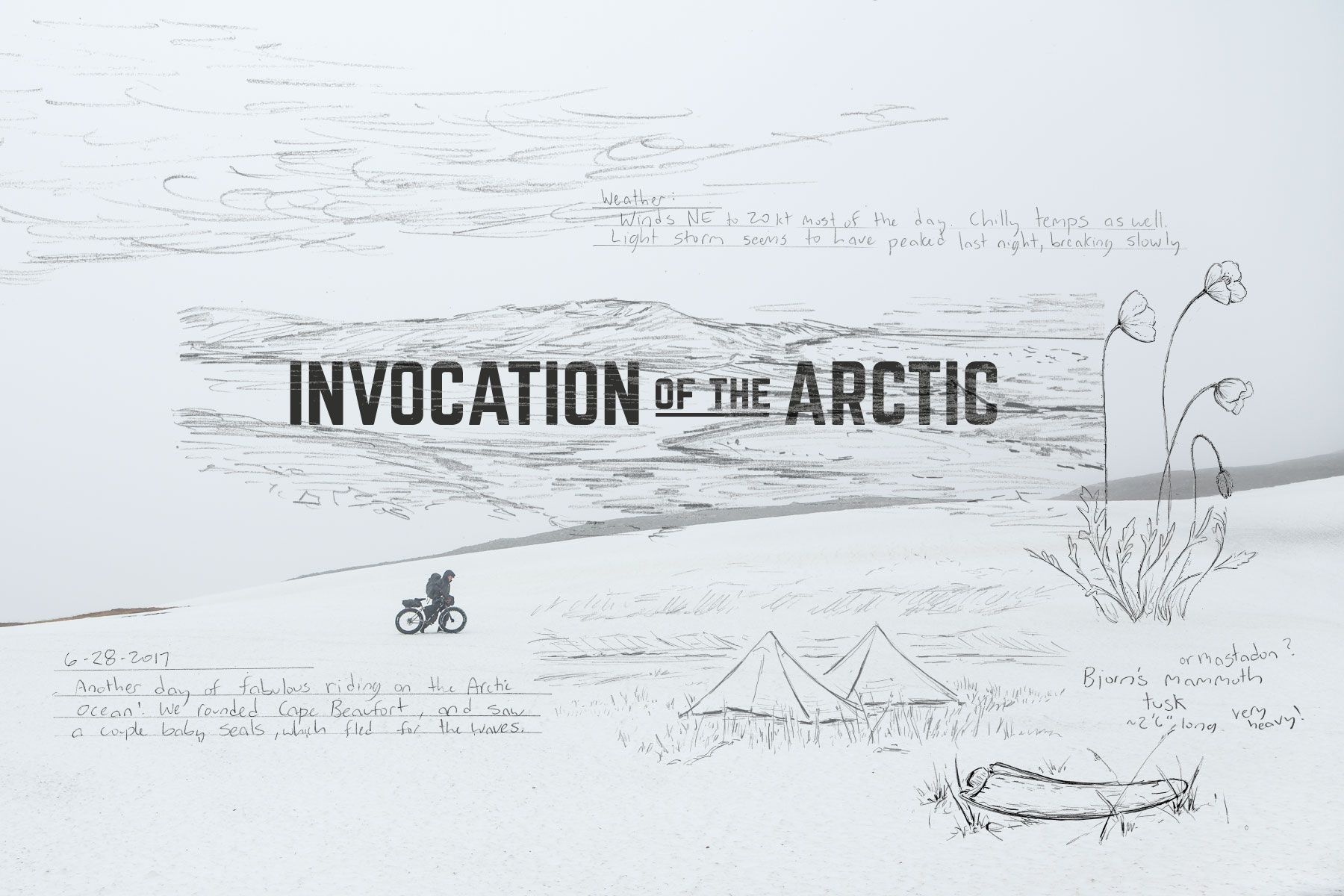

Words and Photos by Bjørn Olson with illustrations by Kim McNett.

We knew there had to be more treasure. I steered my bike around bloated seals, half-rotten walruses, and graying whalebones, squinting for a gleam of ivory. Two days earlier, one of the four of us spotted a perfect, sun-bleached walrus skull with two beautiful and intact tusks.

With a big rock and brute force we broke the prized ivory free. A few hours later we found another lone tusk poking out of the sand. One more find would assure each of us a precious Arctic souvenir.*

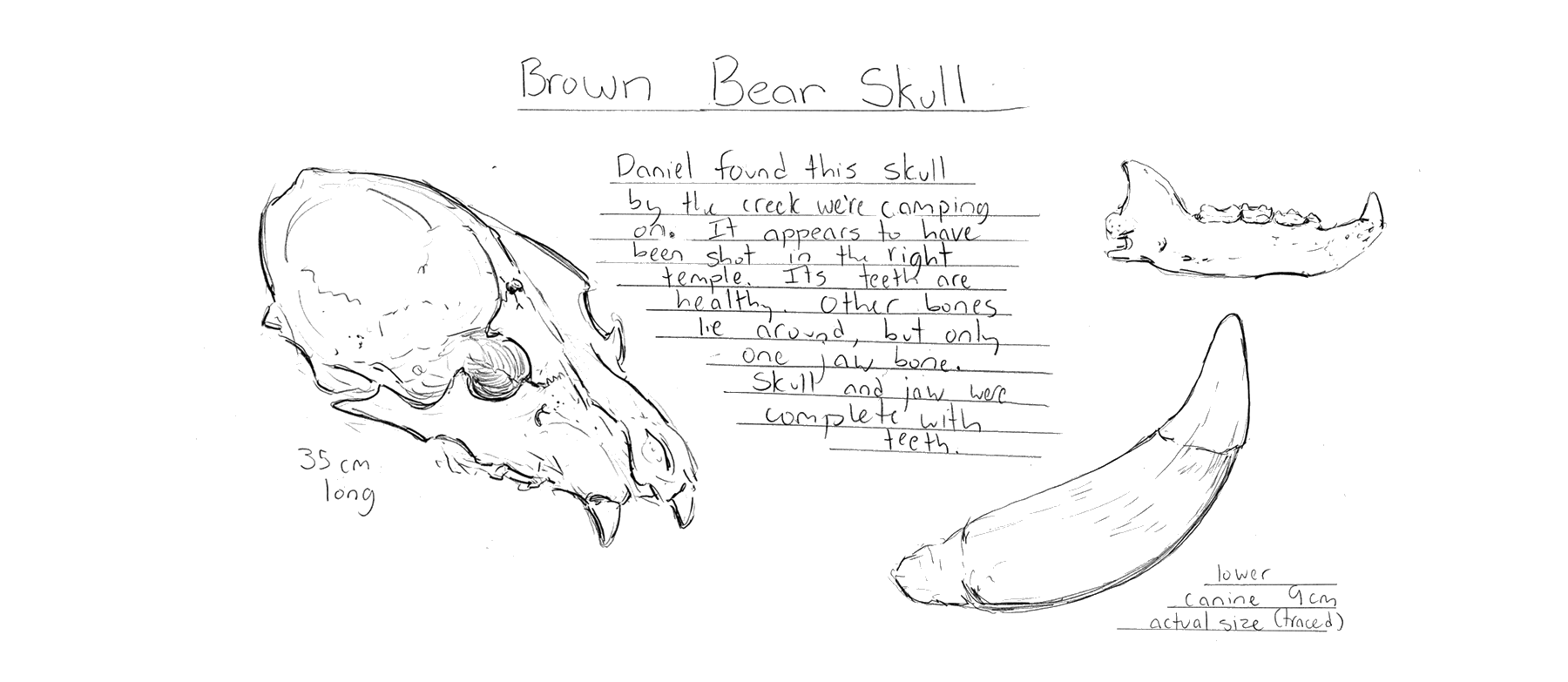

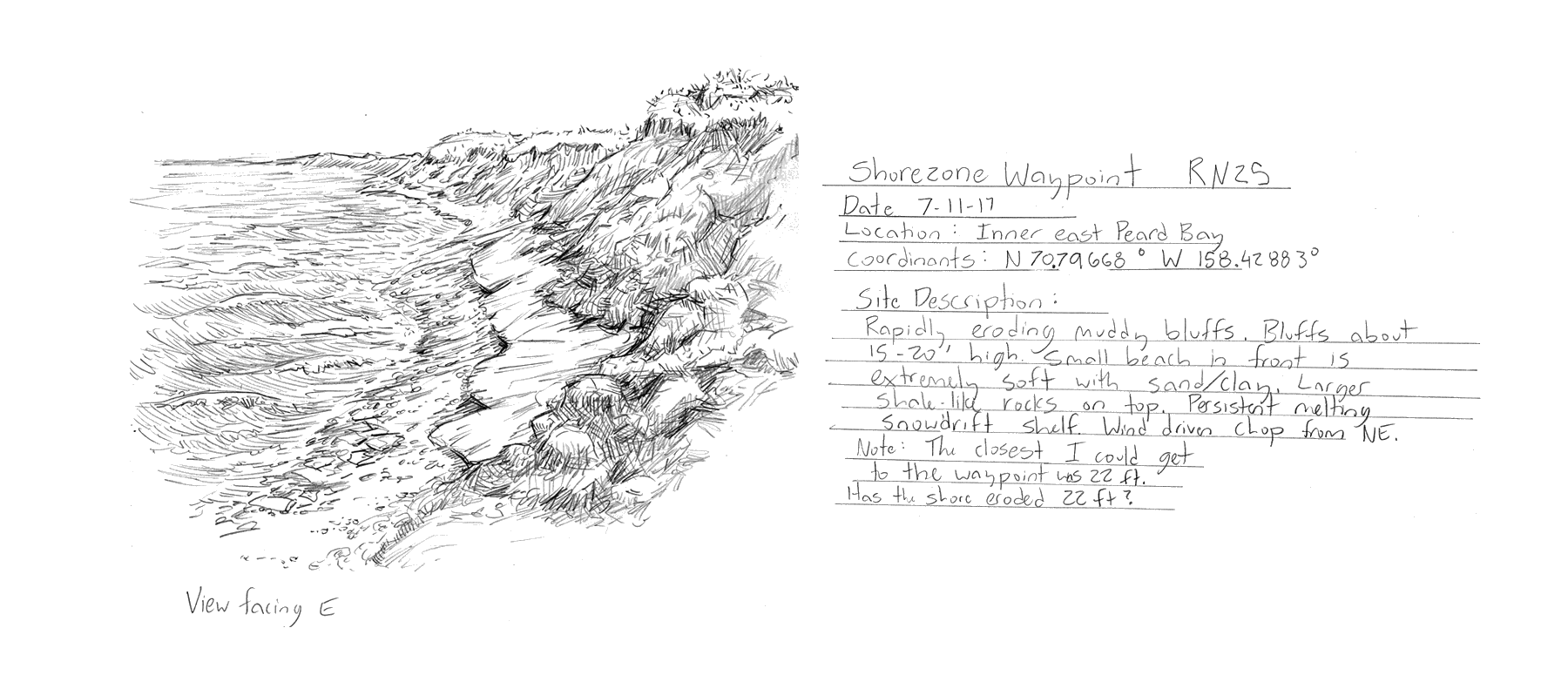

The oily stink of decaying flesh from the naturally deceased sea mammals that periodically littered our route is a dinner bell for the regions brown and polar bear. Like nervous seal pups, our attention periodically scanned the macro-verse of our wild surroundings and then snapped back to probing for ivory atop the beach or poking out the eroding permafrost.

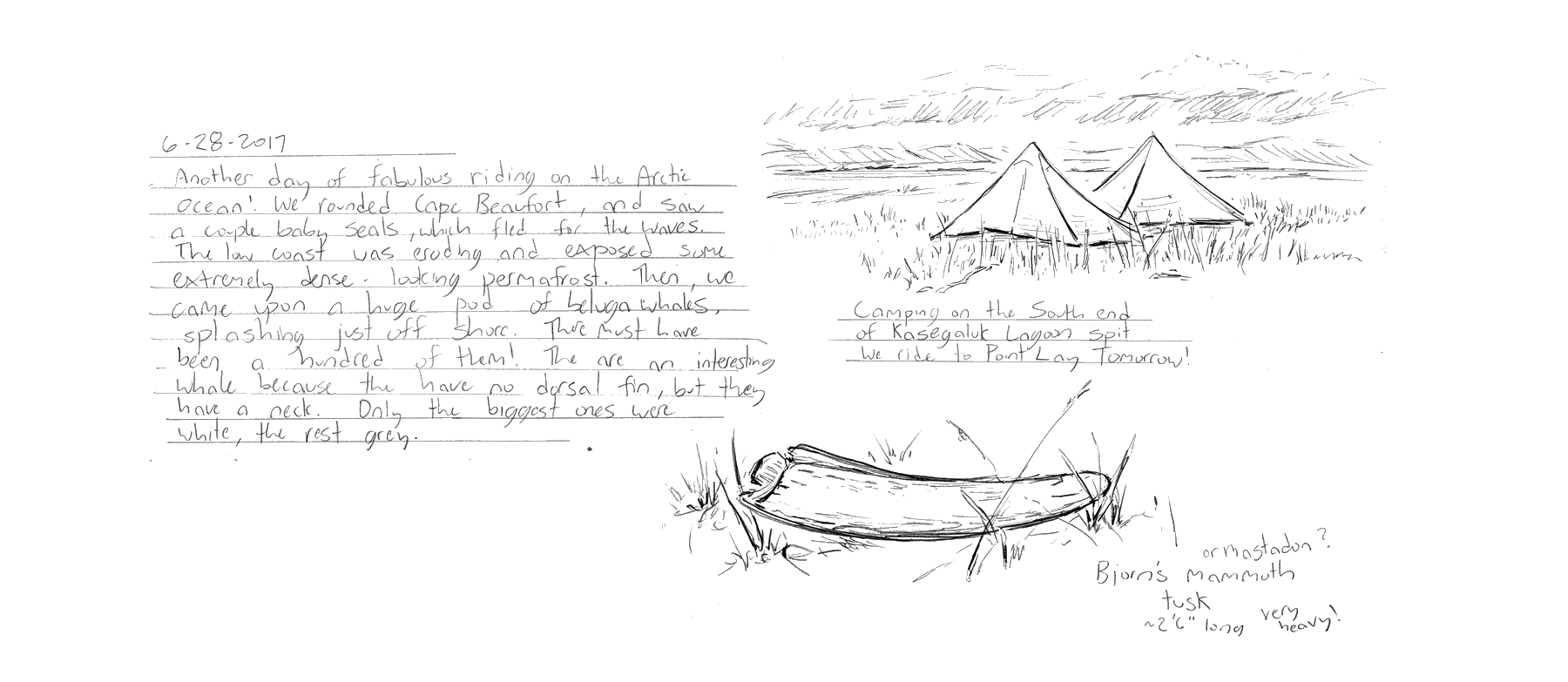

Fat-biking on beaches involves constantly seeking firmer terrain. Sometimes the fastest conditions are near the water’s edge, where waves compact the sediment, other times above the berm, and sometimes, inexplicably, right in the middle. Seeking a faster line, I rode a wide sweep of the beach from the bottom to the top. As I crested and began my arc back to the breaking waves of the shore, I spotted one. Eureka! Another tusk.

I set my bike down and picked it up. I felt the heft, observed the girth and, for a moment, stood in stupefaction. In my hands was not an ivory canine of a recently deceased walrus. It was far too big and far too heavy. It was, however, ivory. My mind raced and cheeks flushed. Within my hands was the most sought after of Pleistocene finds—a mammoth tusk!

Most of the great hairy elephants of the North went extinct during the last glacial retreat, some ten thousand years ago. Isolated pockets of mammoth survived on islands and within islands of land surrounded by ice, but the youngest fossils are still thousands of years old. In a quiet state of surprise, I held the tusk up for my three companions to see. A proud elation overtook us all.

We were on the shore of the Arctic Ocean – on a trip that’s been a lifelong dream and ambition. Traveling in remote areas of Alaska by human-power has been a passion of mine since I was a teenager, when I greedily read stories about great adventurers like Knud Rasmussen, Roald Amundsen, and others.With a fat bike and a packraft, creative and untested routes exist again, and these instruments have opened a new era for original wilderness exploration.

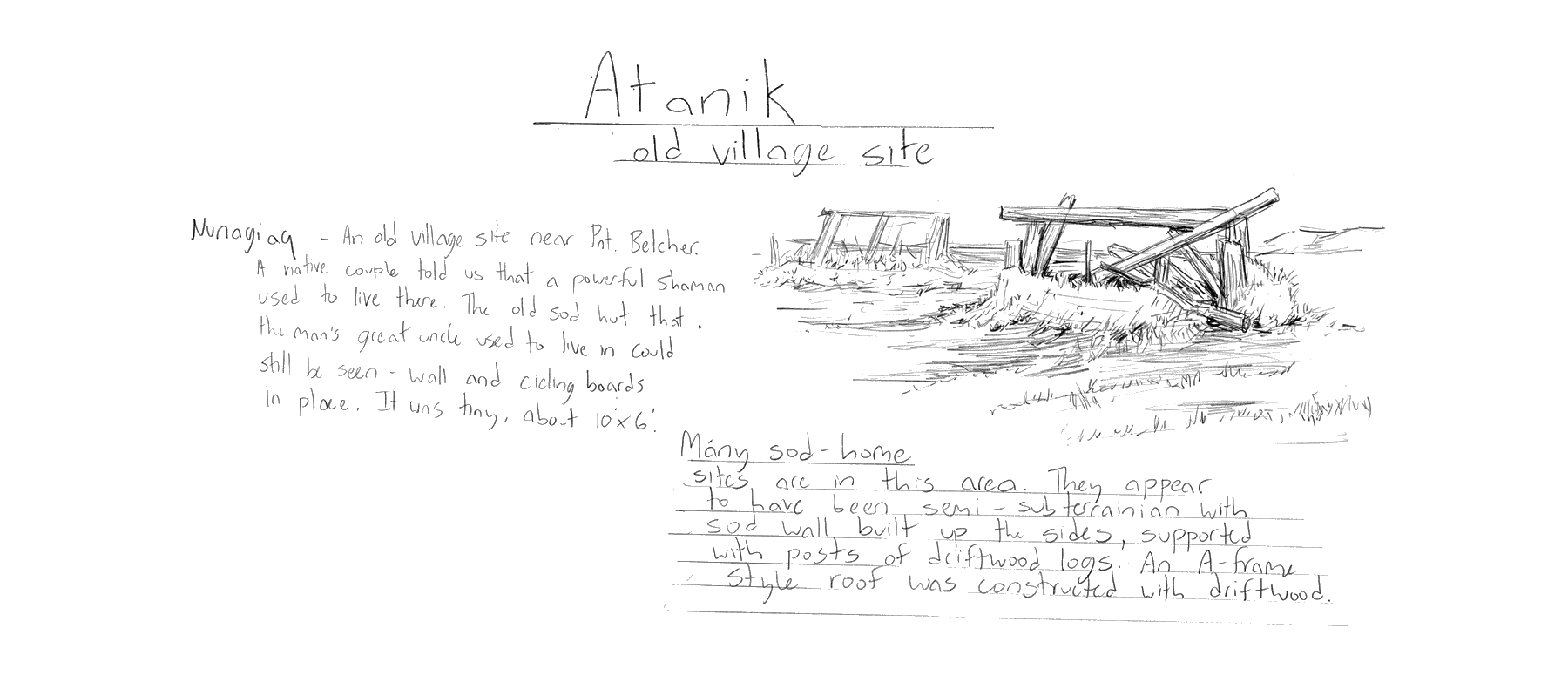

For much of the previous winter, my life-partner Kim McNett and I schemed on a bicycle traverse of the roof of Alaska – from Point Hope to the northernmost community in the U.S., Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow). On Google Earth, we zoomed in and out, swapping between the USGS topographic layer and back to satellite view, trying to envision the terrain.Few modern adventurers have made this trip by human-power and, as far as we know, no one has tried to employ a bicycle. Yet, for thousands of years, America’s first people trod, paddled, and dog sled along the north shore of Alaska. Many continued east through the Inuit Passage (Northwest Passage) all the way across the Canadian Arctic and onto Greenland. We would be traveling in the shadows of Alaska’s oldest ancestors.

Four days after finding the mammoth tusk and twelve days after setting out from Point Hope, we neared the first village along our route—Point Lay. Our traverse had been punctuated with days of hurricane force winds, bear encounters, an overland ride over the western Brooks Range, and many hard fought miles. We needed food and rest. The village would also be the end of the line for our two companions. From Point Lay, Kim and I would continue on to Alaska’s summit alone.

The Kasegaluk Lagoon—a long chain of narrow, sand and gravel islands—had, for several days, been our path-of-least-resistance. Short channels of water separate one island from another. By the time we reached Point Lay, our reflex for rapid transition from the bikes to the packrafts was efficient and instinctual. A brief, one-mile crossing from the island to the village remained.

On bike-rafting trips, every thing has its place and nothing is extra. For days, I had made allowance for the ten pound, two-foot long piece of fossilized ivory. Soon, our friends Daniel and Alayne would depart in a single engine plane, bound for home in southern Alaska. With them, would go my prized tusk. I set the awkward thing on my lap for the last time and pushed off into the water.

Nalukataq is the Inupiaq Eskimo version of Thanksgiving. This ancient festival honors the bowhead whale and the brave hunters who risk their lives to bring them home. Special allowance for indigenous Arctic peoples — whose cultural identity and very survival are intricately linked to the whale and whale harvesting — have been made by the International Whaling Commission.Over the last hundred years there have been innovations in whale hunting technologies, but the core of whaling still involves traveling offshore on spring sea ice and launching into lightweight and fragile skin boats into open leads of water, risking everything for the opportunity to harpoon a leviathan creature, one capable of feeding hundreds throughout the long, cold year ahead.

In our modern age, there are few examples of selfless bravery like that of an Inupaiq whaling captain and his crew, providing for the very real survival of their families and community. Nalukataq is the festival that honors and celebrates the hunters, tributes the bountiful sharing, draws community together and, most of all, pays respect to the creature that supports a people on the very edge of the world — the whale.

Unbeknownst to us, we were arriving just in time for the festival.

“Welcome to Point Lay,” a man on a four-wheeler said as I stepped from my raft. “Want to buy an ivory ring?” My three companions landed and for a moment I felt overwhelmed. “Umm,” I stammered. “Give me a second.”

I pulled my raft the rest of the way out of the water and opened the valve to let the air out. While I addressed my chores, the man’s eyes caught the mammoth tusk. In the archetypal manner of a soft spoken Inupiaq hunter, he gently said, “Our elders don’t like it when outsiders take artifacts and treasures from our land. I don’t care, but I am just letting you know. Maybe hide it in your pack or something.”

For a moment I considered what he said. Most outsiders who visit the far north of Alaska come for jobs on the North Slope oil fields or other high paying, quick money schemes. Few of them show respect to the environment or its people. I picked the tusk from the floor of my raft and handed it to the man. His eyes widened. Being a friend and being made welcome was considerably more important than the tusk.

“Are you sure,” he said. I nodded yes. He held it in admiration and then slipped it into a bag behind his seat. The value of a mammoth tusk to a carver supporting a family is not insubstantial. “Take a couple rings,” he offered.

In the village, kids flocked to us and our freakish looking oversized bikes. “Can I try?” They asked. “What’s your name? Where you from?” The adults, mostly busy butchering whale meat, all made it clear that the Nalukataq festivities were beginning soon. News of our travels preceded us and everyone we met insisted we attend the festival, join the feast, and made us feel welcome.

Over the last ten years, the fat-bike and packraft have been rapidly evolving in form and functionality. Both were originally conceived and developed in Alaska, but the efficiency and practicality of both have caught the imagination of people worldwide. What can be done with a fat-bike in conjunction with a lightweight, one-person packraft is still being discovered.

Four hundred and fifty miles and three weeks after setting out, Kim and I pedaled the last soft and grinding miles into Utqiagvik. The host of fears I had before leaving home had dissipated and our rhythm for traveling in the wild and remote far north was beating a steady pulse. The Arctic had been kind to us.

*We at BIKEPACKING.com follow and promote Leave No Trace outdoors ethics, including the ‘Leave What You Find’ principle. It’s worth noting that walrus ivory is commonly collected, and the gathering of it is approved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.