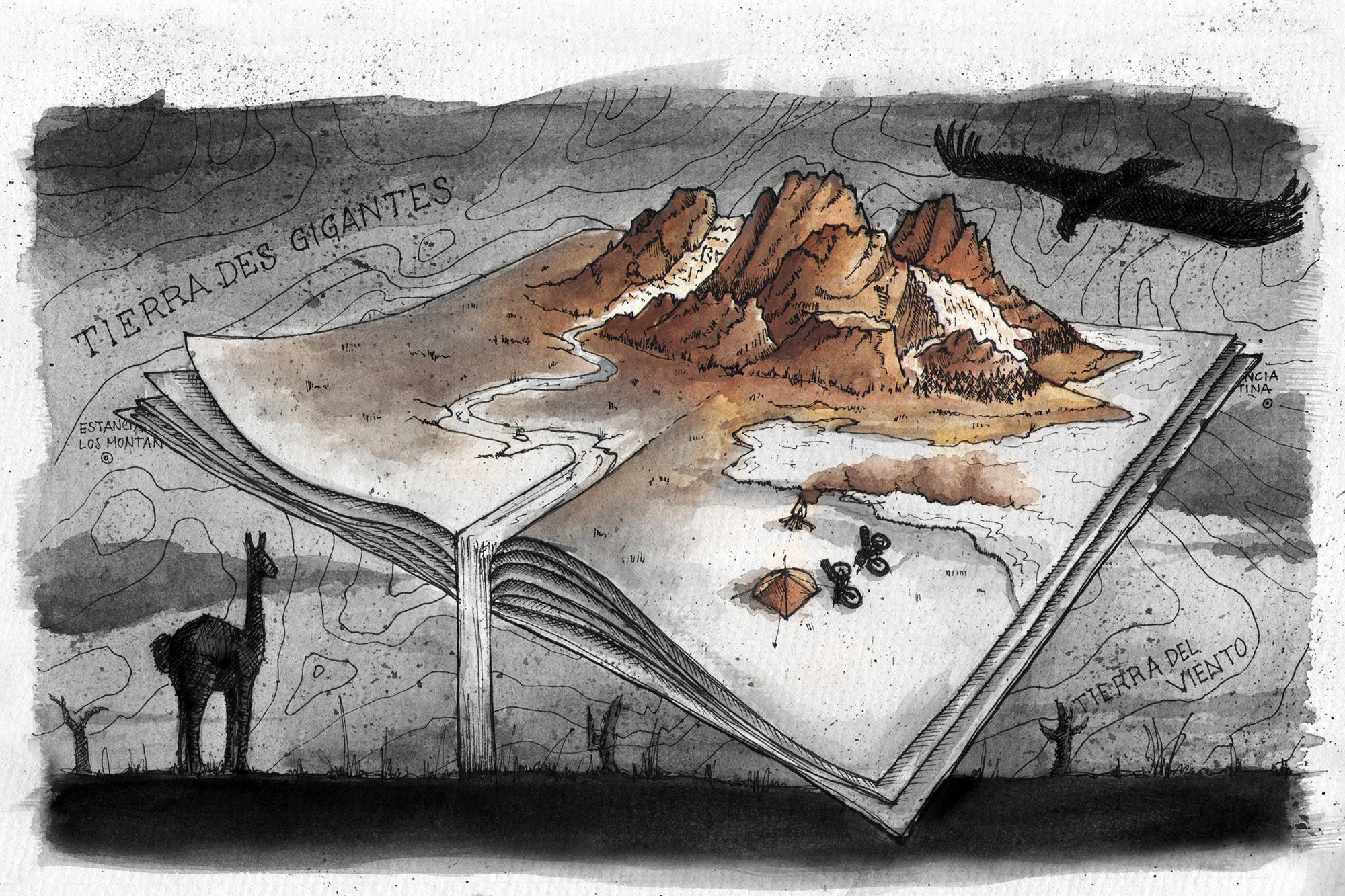

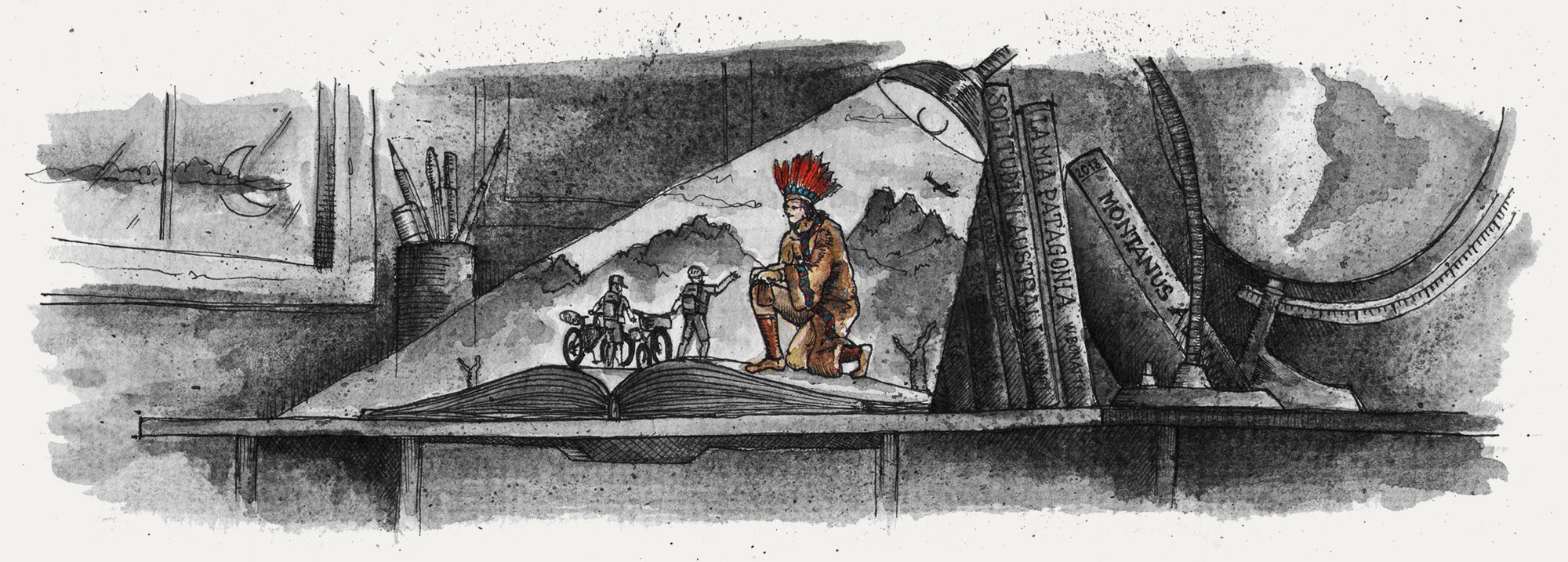

Patagonia, Tierra De Gigantes

The idea for this journey was gleaned from the pages of an old book, one in which Walter Bonatti, Italian alpinist and explorer, describes the exploration of a remote and wild land. Once inhabited by monsters and giants, today its name still evokes adventure and exploration. Patagonia. Driven by his story, we found ourselves flying over the Atlantic Ocean to discover it for ourselves.

Airborne above the Andean Cordillera, we could see an alien world from our windows. It was one that exuded the same strength and awe as it once did for the former explorers of the Old Continent: the Patagonian steppe, arid and boundless, the San Martin, the Viedma, and Lago Argentino. They’re all united by the tortuous, twisting course of the Rio Leona and the Rio Santa Cruz, which, after a run of 150 km across the steppe, flows into the Atlantic Ocean. These mighty features combine to form an incomparable and unreal scenario.

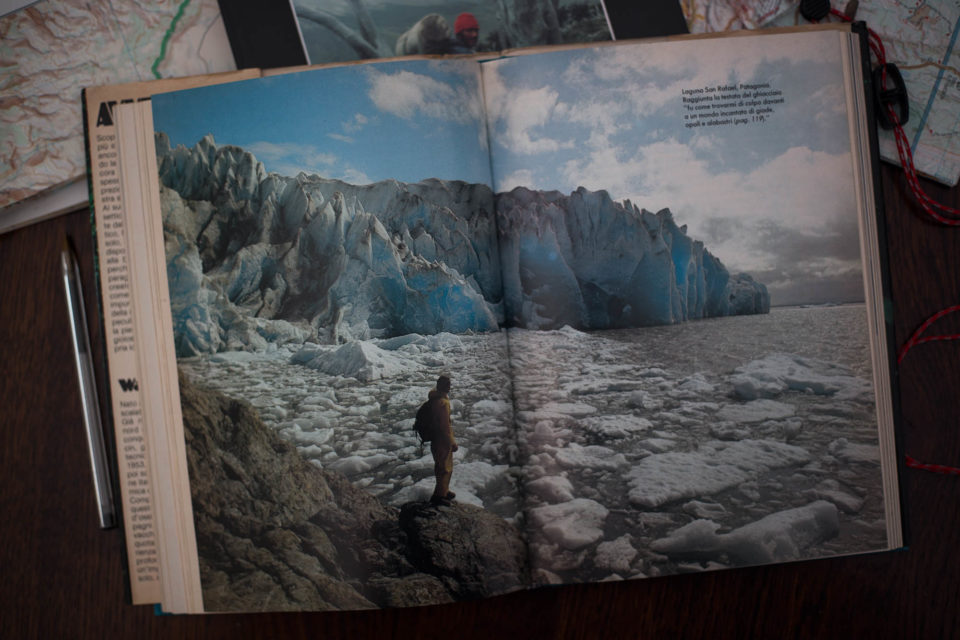

Fitz Roy and the Cerro Torre stand tall in the distance, the majestic peaks of the Hielo Continental Patagonico, a huge perennial ice shelf, the world’s third largest water reservoir after Antarctica and Greenland. The same environments imagined and so precisely described by Bonatti emerged from the pages of his book and became reality. This majestic landscape accompanied us until we landed at the small El Calafate airport, an Argentinean town located along the shores of Lago Argentino, in southern Patagonia’s Santa Cruz Province.

The center of El Calafate has developed to accommodate the needs of tourists, while the suburbs are modest, inhabited mainly by families of natives and local workers. We spent a couple of days relaxing to recover from the long journey, between excellent Argentine empanadas and local beers. On our third day in country we spent time setting up our bikes, invading the garden of our small hotel. Here, we met Lukas, a Swiss geologist who was intrigued by the chaos we’d generated on the lawn. He started asking questions about the strange bikes, especially the “rolled up yellow and black sheet.” He was stunned when we revealed that it was a packraft, one of the compact and light dinghies with which we intended to navigate the glacial basins. Lukas knew Patagonia quite well, he’d been working here for years, and he warned us about extreme and changing weather conditions of this region: “Sometimes, the wind is so violent that you feel as if the debris is piercing your face. On the lakes’ surface, air and water tornadoes rise for several dozen meters, putting even big boats in danger.” We already knew about the strength of the wind that whips through the region, and we were all too aware of our limited experience with our small boats. In fact, we had very little time to test the packrafts since they arrived just a week before our departure to South America.

The Last Tehuelche

We set off on our tour the next morning, but before getting on the bike we decided to grab some empanadas for the road. The La Familia panaderia was right in front of our accommodation, so it was the natural choice. It was a small family-run bakery, with a hand-painted sign on its pink facade, where Jose, a former chef who set up his own business, produced not only bread, but also excellent take-away food. There were no empanadas to be found inside on that day, however. It was a Sunday, and there were only desserts available. I fell back on a couple of chocolate croissants. Kindly refused my money, Jose wished me “buena suerte” for the trip. He told me he has to work hard because the current economic conditions are not the best. I could tell he was a good man. After thanking, him I invited him out for a souvenir photo and we said goodbye. He went back to work as we began packing up our bikes. After some pedaling, we could hear Jose screaming something while he ran after us. In his hand he has two croissants, one for me and one for Giorgio, too. Viva Argentina!

We left El Calafate along a dirt road that led us toward the Patagonian Andes through the dry and windy steppe. Forward progress was difficult because of the wind and the uneven ground that made our bikes jump like bucking horses. The headwinds picked up, covering us with dust. We rode without speaking, the wind incessantly whistling in our ears. My mind seemed to be covering more grounds than my legs, and I couldn’t help but sink deep into thought, as I often do in moments like those. My mind went back to Jose and his kind gesture, and how true it is that people who have the least are also the most generous.

Letting my mind wander further, I thought about how in 1520, during his circumnavigation of the globe, Ferdinand of Magellan characterized the Patagonians as “Giants” because of their stunning height. For this reason, initially, Patagonia was called “Tierra des Gigantes,” and on early maps and books the natives we represented as real giants. Even today, we kept our eyes out for scientific evidence of the existence of the Patagonian giants once spotted by Magellan. We eventually came to understand that Josè, like the other natives we met, are people of great heart, true “Giants” of generosity.

Estancia, Bastion of the Simple Life

Wind subsided and the noise of our tires on gravel brought me back to that never-ending road. The monotony of the moment was broken when a hare came out from a bush and crossed the road. In a split second, an eagle landed, grabbed it with its claws, and, in a cloud of dust, carried it to the roadside, starting to devour it instantly. It was a raw scene and our introduction to Patagonia’s truly wild nature. We were so close to that splendid bird of prey that we could almost feel the hare’s flesh tearing, and Giorgio managed to photograph that shocking moment of life and death.

“Out here, as in Cape Horn, the birds let themselves be approached until a few steps, ignoring the existence and character of the man they do not consider, by instinct, a threat.” Walter Bonatti, 1971, Patagonia

Meanwhile, the sky had darkened above and was creating the look of almost apocolyptic conditions. Threatening clouds, driven by ocean currents, rose up and obscured the Andean peaks of Hielo Continental Patagonico. We got to back pushing on the pedals through the endless steppe, populated apparently only by yellowish bushes.

Some time later, dotting the hills not far away, we saw a herd of guanaco watching us, intrigued. The curiosity was mutual, so we stopped riding to take some pictures. A big male came towards us, positioning itself between us and the herd. After staring at us for a few seconds, it emitted a strange cry, halfway between a hyena’s laugh and a horse’s neigh. Calling the herd back to order, it slowly disappears with it behind the hill.

The Andes grew closer still as we finally we kept a good pace for some calm miles. The headwind returned, bringing with it the terrible stench of carrion. Further on, along the roadside, we found the badly decomposed body of an armadillo, the upper part of its armour shell torn off and its insides emptied. It was likely the combined result of a run in with a car and later an Andean condor, the king of the high Patagonian peaks and the largest bird of prey on the planet with its three-meter wingspan.

After crossing the vast plateau, a rapid descent took us back to the same altitude as Lago Argentino. With our backpacks starting to become heavy, but the huge Patagonian steppe now behind us, we knew it was only a little further ahead until the entrance to the Parque Nacional Los Glaciares. We followed a detour towards the valley along the south arm of the lake. The road becomes narrower and eventually ended after few kilometres, near some rural buildings covered with corrugated sheets. The dark green roof and light beige walls made the estancia, or traditional Argentinian farm, feel in harmony with this beautiful Patagonian setting.

The light was incredible, even magical magical. It filtered through the clouds, shining behind us and breaking on the mountains, outlining the shapes of the glaciers and their light blue veins. It was most silent of places, disturbed only by the squeaking of an opening gate. We stop in front of the largest shed, and shortly after, perhaps intrigued by our voices, we met a gaucho in his forties, wearing a beret, his face darkened by the sun, with a proud and determined look, and powerful arms and hands. Despite his hard appearance, Mario was an affable person, and he welcomed us into the estancia where he worked, inviting us to enter the shed.

Mario spoke only Spanish, but could somehow understand each other. Inside the shed, he showed us some old tools and machinery that was used at the beginning of the last century for shearing and treating wool. He told us that the wool, once treated, was loaded on the carretas, huge wagons drawn by a team of about 18 animals – a mixture of horses and donkeys – to reach the port of Rio Gallegos, on the Atlantic Ocean, after a journey of more than twenty days.

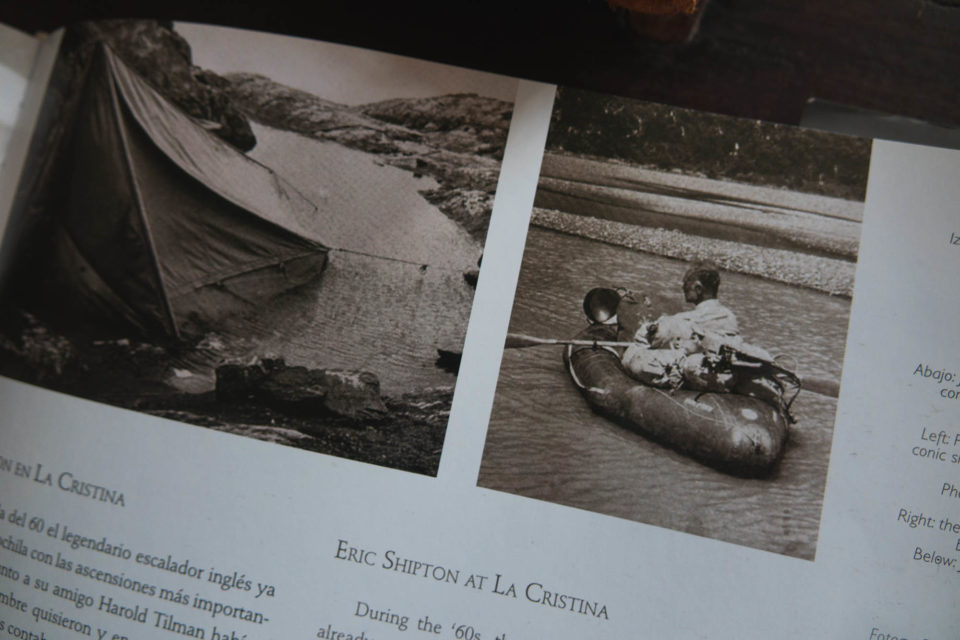

Mario then looked at our bikes, intrigued, and asked us where we were heading. With gestures and improvised Spanish, we tried to explain to him that we were going to explore the valley in the direction of the glaciers, using packrafts to cross the lake. As soon as he understood our intentions, he rushed out the shed, signaling for us to wait for him. When he came back, he had a book with him. He flipped through it quickly and then he showed us an old black and white photo of a man on a packraft. Unbelievable! The caption indicated that it was Eric Shipton, one of the most famous English alpinists and explorers who explored Lagos Argentino and Viedma on a small dinghy in 1958. And while our astonishment was great, even more so was our hunger, so we decide to spend the night at the estancia to taste the asado, the Argentine roasted meat, a typical dish of gaucho culture.

The estancia was in full swing when we awoke the next morning, and the gauchos were already at work. Some of them went away on horseback to graze the sheep, one tamed the colts in the corral, one practiced with a lasso, and another rounded up cattle. Mario was the most capable gaucho of the estancia and excelled in all the tasks. He was engaged with milking cows, and was proud of his lifestyle and work. The gaucho, traditional to Argentine culture, is at serious risk of extinction, particularly in this digital era, completely focused on mechanizing and producing everything fast and at the lowest cost.

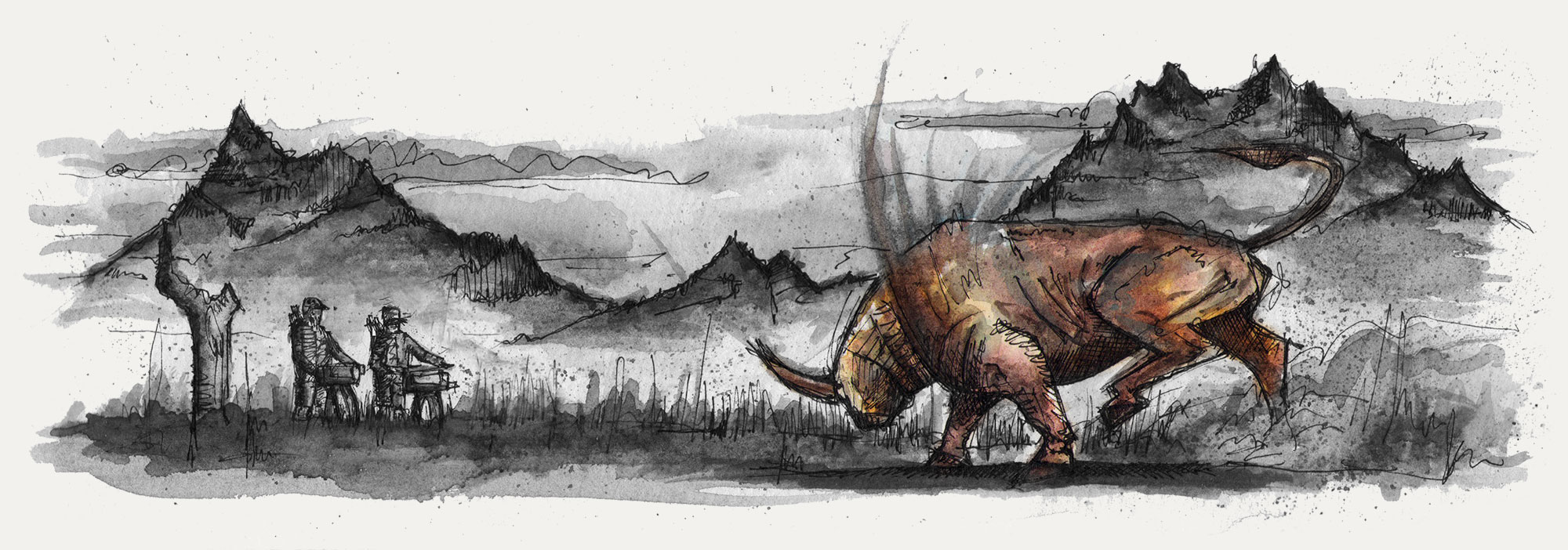

We started packing up and Mario noticed that we were preparing to leave. He comes to greet us, shouting, “Buena suerte, amigos!” He shook our hands energetically with one hand, while holding the Porongo in the other, a container made of pumpkin, from which the Argentines drink mate, a brew derived from Yerba Mate leaves, a plant native to South America. Before returning to his work, Mario warned us of some dangerous animals living in the area where we were headed. Specifically, the puma, known in North America as mountain lion, and the Patagonian Criollo, or Patagonian Creole cattle, a wild bovine that has developed the ability to deal with the region’s frigid winter temperatures, a unique species in the world. We struggled to imagine cattle outside of a farm corral, yet these incredible animals survive in the most remote and extreme areas of Patagonia. Mario told us that the biggest mistake is to confuse them with the cattle we know. This wild bovine is not docile at all. It’s aggressive, he said, and it’s able to kill even a horse, often charging for no apparent reason beyond crossing its path. Noted.

The Patagonian Creole Cattle

In South America, before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores, there was no trace of cattle. They were introduced from Spain around 1549. They later reached the pampas and then southern Patagonia, where the extreme conditions and natural selection turned them into a new breed, known as Creole. Some of these species became wild during the destruction of the colonies and the Spanish herds by the native Mapuche and Tehuelche, taking refuge in the Andean forests. Today, a small number of feral cattle live in the south of Los Glaciares National Park, between the great Patagonian lakes and the Andes.

Roars and Thorns

We followed an old doubletrack road, one that sometimes got lost in the tall grass, and left the estancia behind. We got to high ground, from which we could admire the sumptuous beauty of the place. The Andean glaciers dominated the valley, and huge, fast-moving cloud formations provided for spectacular light and shadow effects. Further away, towards the south, where the valley tightened, we saw rainbows with an intensity we’d never seen before. They emerged near the turquoise waters of the lake and ended among the white peaks of the Hielo Continental. We stood for a few moments to admire the vast and wild beauty. Places like those can captivate the soul and take it to another dimension.

In the distance, perhaps a couple of kilometers from us, we could see a sprawling beach and decided to head there to spend the night. Sudden rain shows and wind gusts alternated with flashes of sunlight, causing significant changes in temperature. We were forced to put on and take off our rain jackets several times during that small stretch.

Reaching the beach was anything but easy. We labored ahead, advancing with considerable difficulty over the rough terrain. Hidden among the tall grass were prickly plants that slaughtered our ankles and calves. One is the Calafate, a plant symbol of Patagonia, with small and very green leaves, delicious berries, and long, hard spines. The other one, whose name I forget, is small and evil, with numerous stinging spines. These ones anchored themselves tenaciously to our socks, causing small but unbearable lacerations on the skin, especially when they got inside our boots.

Before long, we had to stop to remove countless thorns from our socks, an operation that required a lot of time and caution since the thorns can break and get stuck in the epidermis. It was a waste of time, though, because after a few steps our socks would be completely covered again. The thorns tormented us the whole way, attacking our ankles every time we got off the bike to push. They were omnipresent and unnerving , leaving us exhausted.

Finally, we reached the beach, where we set our bikes on the ground, removed our socks, and dipped our feet in the icy water to ease the pain. We set up camp and ate something in front of a fire we lit with wood found on the shore. It was dark, the lake was still on the horizon, there was a pair of lenticular clouds and, immediately below them, the shape of the Andes. The crackling fire, the voice emitting from our camp, projected our shadows onto the tent. It was just us and Patagonia. Suddenly an incredible roar shook the valley. It was a terrifying noise, like thunder, but more violent, frighteningly violent. It seemed to come from somewhere behind the mountains. Taking it as a sign that it would soon rain, we decided to slip into the tent. The roar returned as we turned off our headlights, this time sounding more like an earthquake. Earplugs in, it was time for sleep.

At the Mercy of the Elements

A gust of wind hit me square in the face, like a violent slap, and I woke up with a start. I could feel the sand between my teeth and in my nostrils, and as soon as I opened them, it also got into my eyes. It was chaos! Giorgio isn’t in his sleeping bag and the tent was open. Another gust of strong wind hit me in the face again. It turns out Lukas, the Swiss geologist, wasn’t exaggerating when he told us about the face-piercing debris. I removed the plugs from my ears and quickly looked for the headlamp. “Gio, where the f*ck are you?!” I shouted, but my yelling was drowned out by the roaring of the wind, and I could distinguish only the sound of the waves. I felt the water nearby, very close now.

Giorgio came running back to the tent and shouted, “It’s a mess here! We have to move the tent, now!” Quickly putting on my shoes and jacket, I headed outside. The water was less than a meter from the tent and the strength of the wind is crazy. We picked the whole thing up, with everything inside, carried it away from the shore, anchoring it with our bikes, some stones, and a few big logs that we recovered from the shore. The lake stirred and splashed as if it was possessed.

Climbing back inside inside, we found sand everywhere. It was in our sleeping bags, our clothes, even in our ears. It was just after 1:00 am and we tried to go back to sleep, but it wasn’t happening. The wind picked up, crushing the walls of the tent with an unprecedented level of violence. Just a small laceration and it would burst like a balloon. We hunkered down in that hell for seven hours. Then, around eight in the morning, everything suddenly calmed down. We rested for 20, maybe 30 minutes, until the sun and the unbearable heat inside the tent pushed us out.

Giorgio left to fill up our bottles with water, and I heard him call out to me shortly after. When I reached him, he pointed to the ground. “What do you think these are?” he asked. On the gravel next to the edge of the river were the unmistakable footprints of a puma. We quickly glanced through the tall grass to check the surrounding area, but we didn’t spot anything except an Andean condor flitting in the distance.

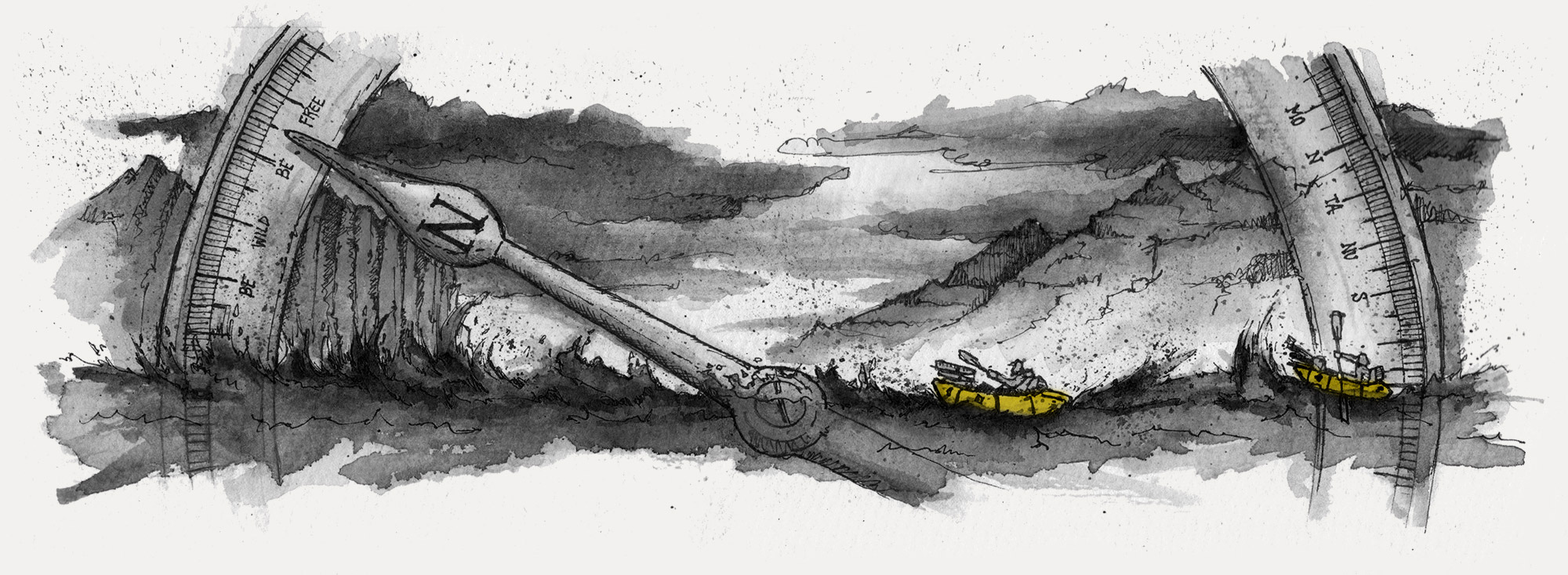

Back at camp, we had breakfast before securing our bikes to our packrafts and we deciding to continue in the water. The weather conditions were perfect, even if menacing clouds were gathering on the peaks. We paddled under clear skies for a couple of hours, until the sun suddenly disappeared and the rain and wind came howling back, though less violently than the previous night. Our packrafts began to shake, but we paddled on through it, though it wasn’t easy. Visibility was extremely low, and clouds of water rose from the surface of the lake and struck us in the face repeatedly. It was a full-on squall, so we decided to paddle to land before the situation got any worse.

Giorgio tried to reach land by making his way through the branches of a submerged tree, but we were close to a rocky wall and, moreover, were exposed to gusts of wind without the possibility of shelter. We decided instead to go back to open water to keep searching. The fatigue from our sleepless night was setting in, but we continued south along a rocky ridge, hoping to find a good place to land. Making forward progress was incredibly difficult as we fought against the wind, the waves, and the strong currents that pushed us against the rocky wall we were skirting.

I could see Giorgio in the distance, who’d stop paddling from time to time to rest his arms before starting again. I did the same, but every time I stopped the current would push me back and I had to work hard to recover the ground I’d gained. By this point, our strength was failing. A bit later, Giorgio raised his paddle in the air with his arms outstretched. I couldn’t understand what he wanted to tell me, but the sign gave me hope. I paddled with newfound energy towards him. He reached land shortly thereafter, and I joined him on solid ground not long later. It was done! We anchored the packrafts using rocks and set up the tent in a dip that was protected from the wind. Exhausted, we collapsed into our sleeping bags.

The Rebel Fugitive

We woke up after 15 hours of uninterrupted sleep. It was probably the most either one of us had slept at once, ever. We made a hot meal, sitting and enjoying it in the sun. Despite the lack of trails, we’d managed continue the exploration of this remote corner of Patagonia, pedaling on the border between the real world and the one we’d dreamed up from Bonatti’s writing.

From the pages of those stories emerged the real Patagonian landscapes: the colossal, icy Hielo Continental rising beyond the turquoise waters of Lago Argentino, where the humid air and the sudden rays of light triggered majestic rainbows of extraordinary natural beauty. We’d breathed the air of true life, of freedom, of symbiosis with our world, one from which we’re too often far away, content to follow the rules of man. We’d snaked our way through the unreal Patagonian landscape, sometimes pedaling and sometimes pushing, without a fixed course or timeline, guided only by the needle of our internal compasses. We were dragged by something primordial and wild, captivated by the incredible wooden sculptures that we saw from time to time, the twisted remains of beech trees shaped by the wind or victims of fires.

We made our way into an area with dense vegetation when a sudden, deafening roar surprised us. It was somehow more impressive and terrifying than those we’d heard the day before. We mistook it for thunder, but it was the sinister crash of a huge avalanche coming off the nearby peaks above us. It crashed into the seracs, reverberating along our legs and up into our breastbones. We stood in awe.

The weather alternated between rain, then sun, then rain again. I’ve never seen so many rainbows in one day. Sometime later, we arrived at a sport where a branched river blocked forward progress. Crossing would be hard because the riverbed was made up of huge boulders, and the risk of sliding and getting trapped or injured was very high. In a wild place like Patagonia, you can only rely on yourself. We put on our rubbed-soled sandals for added grip on the stones, and to leave our socks and boots dry. We made it safely across the slick boulder field with some difficulty, continuing on via a passage through the bushes on the other side.

A little further on, between two huge boulders, we saw something moving. We continued, cautiously, before what we saw froze us in our tracks. A massive specimen of Toro Criollo stood in front us, maybe 50 feet away. It had a light brown coat of short hair, with a tuft of thick fur around its head. Its body seemed to be pure muscle, and its tiny eyes disappeared into its huge skull. It was a wild and aggressive beast with disarming power.

We kept a safe distance to avoid being noticed. We try to take our cameras out of our bags, but, hearing the sound of the zipper, it stopped eating, lifted its massive head, snorted, and stared straight into our eyes. We were paralyzed. Nonetheless, we did manage to take a couple of photos and a short video of it. Before long, though, it started to get nervous. It snorted again, this time with more rage, its hind leg rasping violently on the ground.

We were intruders, unwelcome strangers, and it let us know very clearly. We moved back to a safer distance before it decided to charge us. The sight of man awakens its unconscious memories of the slavery suffered by his progenitors. The Toro Criollo is a rebel fugitive, ready to defend its state of freedom, far from the corrals in which it was imprisoned for many centuries. We weren’t in the presence of an animal, but of an incarnation of the wild spirit. Among those wild lands, we also discovered in ourselves a feeling of being fugitives, beyond the fences, free of the laws of man, fully able to follow the paths of our wild side.

In case you missed it, click here to check out the film made by Francesco and Giorgio on this trip, as well as details about the gear and equipment they brought along. Also, be sure to check out the full gallery on their website.