Near the end of a five day haul across Uganda’s hot, dusty, and relatively flat interior, we sat down at an oasis where we found the rare cold(ish) Coca-Cola. A thirty-something Ugandan named Robert was sipping a pilsner on the bowed wooden bench beside us and asked, “So you are riding your bicycles through Uganda?” I responded by describing our route, listing the names of larger towns we had passed in order to arrive at this point… Bulisa, a small and dusty trading center in the hot Albertine Rift Valley. “You must know how to survive,” he replied, “Living in Uganda is surviving… it’s good that you can travel this way and understand.” I pondered that a bit. Witness? Yes. Truly understand? I think not.

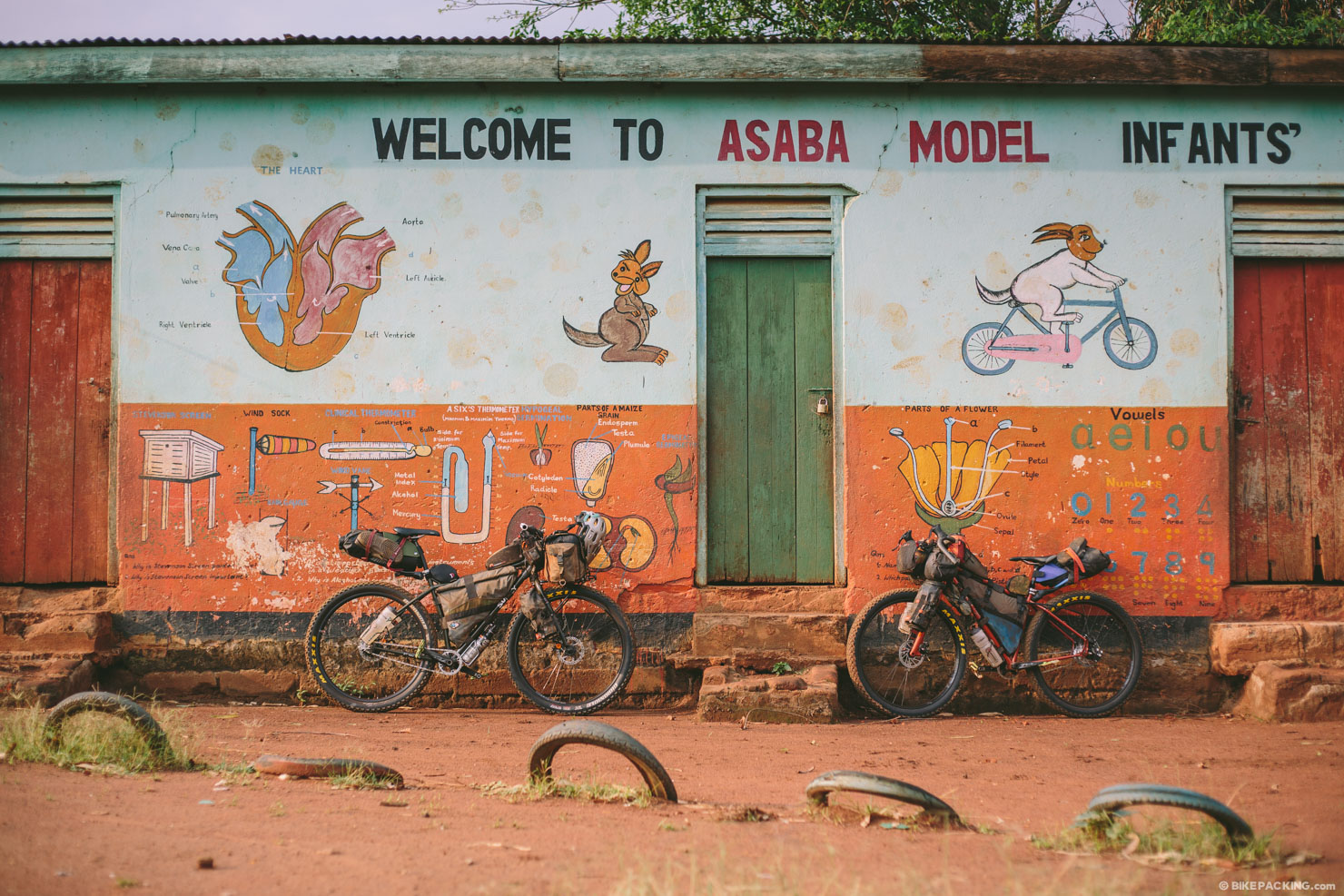

Several days earlier we left the relatively touristed area around Sipi Falls. By touristed I mean that we saw maybe four tourists. After descending the slopes of Elgon, we slipped into Uganda’s central region and a web of tertiary dirt roads, rail trails, and footpaths which meander in and around tributaries north of Lake Kyoga. Scenery changed and the riding was completely different. The slow churning of pedals was replaced by high speed grinds up and down rolling hills. Crumbly dry farmland replaced the lush mountainous slopes of Mount Elgon. Boda Boda motorcycles were replaced by bicycles, evidence of a different economy.

“Living in Uganda is surviving… it’s good that you can travel this way and understand.”

Technically, it’s the shorter of two annual dry seasons right now, running from December through to the beginning of March. Still, there are occasional rains. Nearing the end of one long day in the saddle, a storm forced us to take cover. We ducked under a mango tree, but quickly got soaked in the deluge. A voice called from a small homestead, consisting of 5 small mud brick round homes. Two women motioned for us to have a seat under the thatched eaves of the closest hut. They too had been detained by the downpour; with a newborn strapped to one woman’s back, they were unable to push their banana-laden bike through the drenching rain and accompanying mud. Before the rain had fully subsided, we started pedaling. The locals were already hard at work, tilling the earth to prepare it for planting. These families, sustenance farmers, don’t take a rain during the dry season for granted. The opportunity to sow seeds before the wet season begins could make the difference between full bellies and empty ones.

On this leg of our journey, food has been a little more difficult to come by. Mid-day snacks are limited to what we can find in the tiny mudbrick shacks, usually stale cakes and biscuits that have a questionable list of ingredients, ”edible hydrogenated vegetable oil” and “allowed flavorings” included. Here, the people subsist on cassava, corn and, if they’re lucky, mudfish taken from the swampy tributaries that feed Lake Kyoga. Water is available, thanks to NGO and international aid funded bore holes. But the closest boreholes for some families may be kilometers away from their homes. Gathering water for the day becomes a full-time job. Very often it’s the children of a family, whose time can most be spared, to complete the task. We’ve seen kids as young as four years of age hauling full jerry cans full to their homes. If they’re not transporting water, they’re carrying firewood for cooking. Every minute of every day is filled with the kinds of tasks that we might only practice during camping trips. Hard work isn’t optional. It’s life.

“This is the reality in a country with only a handful of roads that are surfaced with tarmac. Progress stops and starts at the mercy of nature’s whims.”

En route to Masindi Port from Apac, we hit some seriously wicked mud. We hadn’t been caught in the rain this time, but it had clearly dumped buckets prior to our arrival. Ugandan Death Mud is nearly impossible to pass. It’s like thick concrete that sticks to everything, clogging brakes and chains, erasing tire clearance, and adding tons of weight to the load. We were literally stopped in our tracks. A passerby told us we may just have to stay where we were. Unfortunately, where we were was nowhere, and pitching camp would have been difficult at best. Thankfully, a group of village children put off their domestic duties and seemed to rejoice in helping us push through the mud. Eventually a couple of them helped us wash the bikes at a borehole, and the road dried enough for us to continue our ride. This is the reality in a country with only a handful of roads that are surfaced with tarmac. Progress stops and starts at the mercy of nature’s whims.

On a couple of occasions, we’ve had to navigate “main highways”. They’re usually rough and rutted maram (dirt) tracks wide enough for a car and a half to pass. We’d heard that travel on Uganda’s busier thoroughfares wasn’t for the faint of heart. One of the leading causes of death in this country is traffic-related accidents, and that’s really saying something in a country where, unlike the US, relatively few people own cars. So far, our first-hand experiences have validated the rumors… Ugandan drivers don’t give a shit. If there is a car or truck approaching, you get off the road, period. The same rule applies for the countless water bearers and bicyclists carrying roof thatch or firewood. Even children walking along the roadside scatter into the bushes when a vehicle flies by. They must be taught to look both ways while they’re still in the womb. It’s not in the drivers’ nature to give you space. They have the power, and they let you know it. On one occasion, my temper got the better of me, and I flipped a driver off when he came within inches and sent me into a ditch. An onlooker retorted, “This is Uganda.” The words of Robert, our Ugandan acquaintance from Bulisa, resonated. Survival is the name of the game on these stretches.

One evening we were honored to have a wonderful conversation with Father Stanislov, a Catholic priest who permitted us to camp at his parish for the night. At some point, we started to discuss poverty. Dr. Stanislov was quick to point out that there is a distinction between “relative” poverty and misery. His view is that, while many of the people in rural Uganda may lack resources, and they do struggle, they are not miserable. Most have food to eat and shelter. They aren’t without hope. They aren’t truly “poor.” His words reminded me of those found in Buddhist teachings, that “life is suffering.”

Contrary to the tone of these vignettes, Uganda’s interior is far from being a place of despair. The people are incredibly friendly and welcoming. Laughter can be heard everywhere. There are beautiful vistas and experiences woven in the seemingly coarse cloth of life. And, while we are here, just getting by in our own right, I know that we will never truly understand the kind of survival that Robert was talking about. Dodging traffic, eating stale biscuits, and managing the exhausting heat doesn’t compare to endless days of gathering water or knowing that you may be one dry spell away from destitution. We always have an out, we’ve got shillings in our pockets. And, in March, we’ll fly back to a comfortable sofa, made-to-order burritos, and pints of Chubby Hubby. But, what we’ll be leaving behind is truly priceless and far from miserable… Life bursting at the seams and lived in the now. Laughter that’s contagious. And wealth that’s manifested in the richness of family and friends, not in dollars and cents.

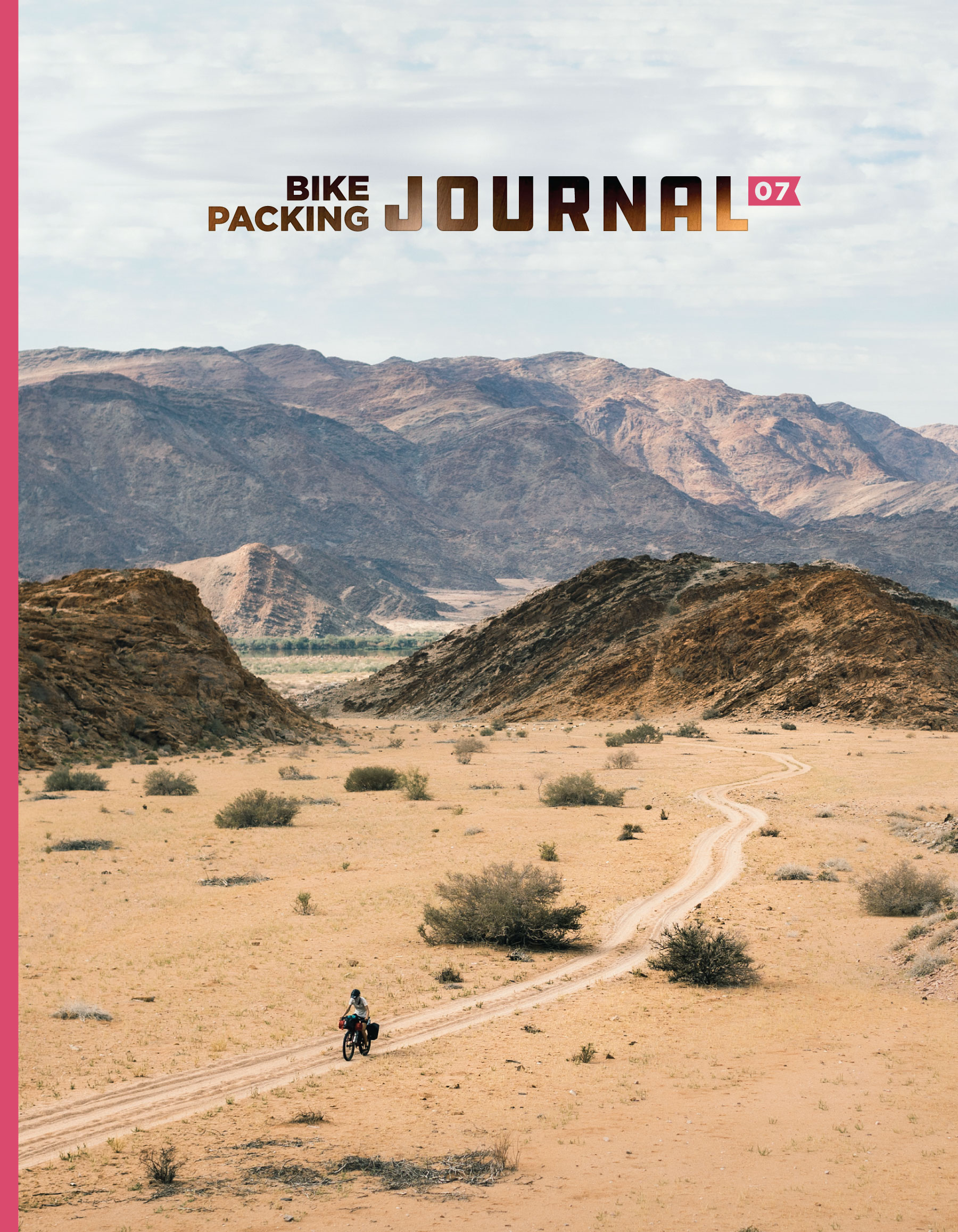

Interested in more stories like this one? Enjoy inspiring writing and breathtaking photographs, all in the full glory of print!

- Twice yearly – New issues are released in April and October of each year.

- Free shipping – Shipping is on us, anywhere in the world.

- Carefully crafted – We've worked hard to create something beautiful and lasting.

- Limited edition – We print one copy for each of our members, and not many beyond that.

- Only in print – There's nothing quite like savoring stories and images on paper.

- Truly independent – This project wouldn't be possible without our members.

- Member Support – Sustains this website and all the content we publish.