Cycle Therapy: Resilience On the Continental Divide

After retiring from his high-stress career as a firefighter and first responder, Chris Christie set out on a head-clearing bikepacking journey along the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route between Canada and Colorado. In this piece, he celebrates the start of a new chapter and reflects on how riding can be a tool to help manage mental health and build resilience to combat the mounting anxiety of daily life. Find his story and a remarkable gallery of images here…

PUBLISHED Jun 5, 2024

Mental health includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make healthy choices.” This applies to not only front-line workers but the general population who feel the stresses associated with negative responses to things such as job satisfaction, family crisis, economy/cost of living, world news, and personal health and wellness.

For over 30 years, the bike has been my constant companion. The feeling of freedom and adventure in exploring the unknown on a bike is transcendent. The early experiences still translate into current-day sensations as an adult while disappearing off the grid on bikepacking adventures. The exhilaration of moving through all types of landscapes and environments has never faltered with time, and the feeling of independence and freedom on two wheels is unparalleled. I spent many years using the bike as an outlet for physical fitness, but over time, I discovered the mental health benefits, not only in my personal life but as a career firefighter and first responder.

Physical activity reduces stress. Stress is an inevitable part of life. Seven out of ten adults in the United States say they experience stress or anxiety daily, and most say it interferes at least moderately with their lives, according to recent surveys on stress and anxiety disorders.

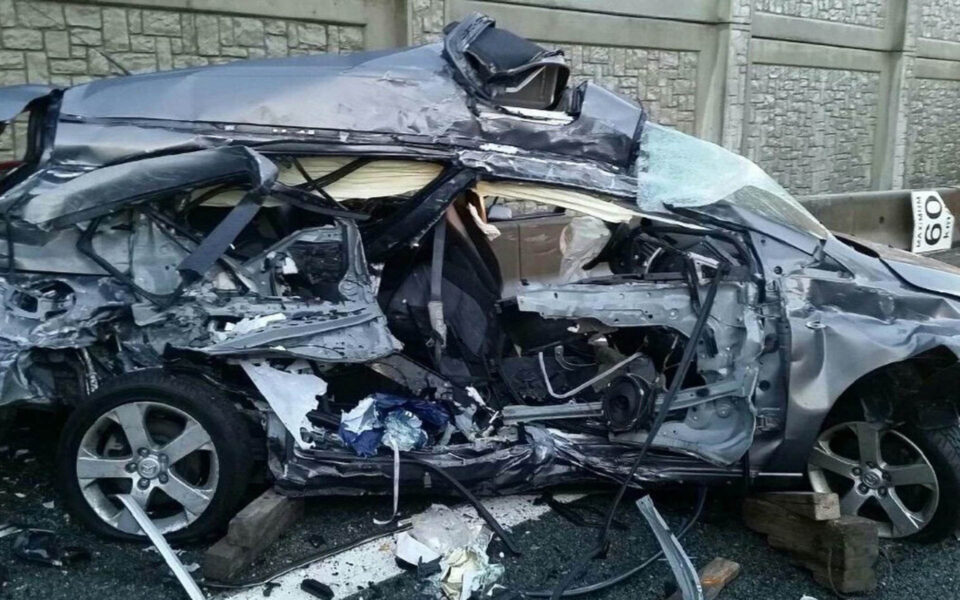

In 2001, at the age of 21, I walked away from pursuing a professional road cycling career in Europe. The markers for reaching the highest level weren’t lining up, and choices needed to be made. I returned to Canada, pivoting toward the occupation of firefighter, and I was eventually hired in West Vancouver. The qualifying criteria initially led me to ski patrolling in the mountains of Whistler/Blackcomb and working as a volunteer firefighter in the Sea to Sky of Squamish, British Columbia, where the main artery between Vancouver and the resorts was widely known as “The Killer Highway.” We were routinely responding to serious vehicle accidents, fires, and medical emergencies along this corridor. The sounds and smell of some calls still linger with me.

PTSD in firefighters. First responder duties, such as rescuing victims from motor vehicle accidents or fire scenes, may also be associated with extreme mental stress, particularly when involving the fatalities of children and young adults. Firefighters directly deal with people’s lives, which requires full awareness and swift life-or-death decision making. Such events may lead to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and chronic occupational stress.

During my competitive years, hours on the road established a foundation of mental and physical strength. Bike racing is hard, and this translated into resilience for life’s difficult moments, where I saw challenges as opportunities to persevere and overcome adversity. This was an asset as a first responder on the scene of an emergency. People often overlook how frontline workers cope with long-term exposure to critical situations, shift work, long nights, and occasionally self-doubt in decisive moments.

Over the years, I recognized how I used the bike to regroup from tension and stress. Operating at a high level in critical situations takes a toll on front-line workers. We are expected to have the ability to naturally cope. Compounding this, we tend to lock away the stressful situations we are confronted with. This can impact personal lives and relationships without realizing or understanding certain reactions in workplace and non-workplace environments.

I ended my career as an officer, and while in that role, I was challenged to think critically while giving direction to peers. My responsibilities included the safety of co-workers and the outcome of those in need. I relate the stresses of being a first responder to experiences on the bike—not necessarily the life-saving moments but in testing resolve. When things are bad, it’s all you know for that moment. Persevere, and those moments will pass. It’s an opportunity to seize the moment and prepare for the next event of uncertainty. Life is hectic, and in the past few years, we have all had some challenges that create daily stresses in our lives, including the rising cost of living, climate change, and COVID and the subsequently stressed medical systems, to name a few.

It’ll make you happy. “Any mild-to-moderate exercise releases natural feel-good endorphins that help counter stress and make you happy,” explains Andrew McCulloch, chief executive of the Mental Health Foundation. That’s probably why four times more GPs prescribe exercise therapy as their most common treatment for depression compared to three years ago. “Just three 30-minute sessions a week can be enough to give people the lift they need,” says McCulloch.

We all need outlets to diffuse. It doesn’t have to be the bike, but it has been shown to be one thing nearly all of us have in common worldwide. It’s one of the greatest inventions for several reasons. These include moving people, transporting goods, improving health, protecting the environment, and connecting with where you are, which is a rarity these days. It encourages mindfulness and the likelihood of appreciating a place’s details instead of speeding by at 70 miles per hour and overlooking the moment entirely.

With my recent retirement from firefighting in West Vancouver, I wanted to celebrate the circle of life on the bike and the outlet it provided for mental and physical well-being after 29 years of frontline exposure. I also faced a huge transition heading into my retirement years. It all sounds ideal, however, new stresses and anxieties about filling time, economics, and future health can manifest when you stop working.

Cycle Therapy

This was a plan to pedal off on a trip that would weave connecting with first responders and using the bike as a tool for mental wellness. I searched for a way to do both and searched for an appropriate route. When the Great Divide Mountain Bike Ride came onto my radar, taking on a substantial portion of it was an easy decision for my partner Julie and me. Its lore online and elsewhere suggests that riding it is widely regarded as a life-changing experience for those who follow it. Julie was part of my career as a frontline worker and was always there supporting the first responder/cycling connection I’ve maintained. She was also in a transition from managing a landscape design business for over 26 years with up to 12 seasonal staff who depended on her for their livelihood. This would be her first summer off in that timeframe.

We started researching the route and working out how much time we could commit to the trip. Most importantly, we didn’t want a tight schedule or a timeline, so we settled on Banff, Alberta, to Breckinridge, Colorado, in 35 days, which would allow one rest day a week and not absurdly long days. The route is well documented, yet the sense of adventure is high with many unknowns due to the sheer distance involved. It has a perfect balance of being off the grid and offering good resupply opportunities. Plus, being around 90 percent unpaved was a huge draw, especially on such a long route.

Filtering the extensive information available can be overwhelming when planning for the Divide, so we narrowed it down to following the 2023 Tour Divide Race Route until some unknown factor suggested otherwise. I felt it had the most current conditions, and we could alter the plan as we progressed. The month prior to departure, anyone considering doing the route watched carefully as British Columbia started to heat up, and fires and smoke were starting to take hold. The interactive smoke map was unsettling, and it left us with feelings of uncertainty. The visibility was less than three miles on the drive through Rogers Pass, but thankfully Banff’s Air Quality Index was rated moderate, and we had no clear reasons to delay our departure.

After two days of frantically shuffling gear between bags and narrowing creature comforts, the bikes finally felt ready for our departure from the chaos of Banff, a world-class tourist town. By this time, a few months had passed since I had left the fire service, and the realization that I was, in fact, partially habituated to my new chapter was sinking in. After having continuity and responsibility to be accountable in a workplace and a team environment for so many years, there is an adjustment phase. Having a plan to be productive with the newfound vacancy in time is important to maintain a strong sense of purpose and fulfillment post-career. These are things that can easily be overlooked. We were fortunate that the bike played a large part in our lives, and with that, it was an overwhelming relief to point the bikes south and start our journey toward Breckenridge.

Leaving the pavement signifies where the adventure begins. Overlooked logistics and self-doubt will be dealt with on the trail. It’s been said it takes five to seven days to find the systematic flow in bikepacking, something Julie and I both hoped we would find, as the entire plan was daunting despite our experience in mountain adventures and backcountry trips.

The dots started to connect, and the days quickly ticked by as our southerly progress fell into a pattern. The cliché of ride, eat, and sleep doesn’t apply on the Divide. There are endless micro-decisions necessary for success along the way, and the diverse landscapes are awe-inspiring. Just south of Whitefish, at a camp slightly off route, we connected with Alex, who’s based out of Vermont. Our objectives, pacing, and mindset quickly synced, so we traveled as a trio for much of the remaining journey.

Our efficiency in packing, unpacking, and finding items in our bags without pulling everything apart was now a reality, and we adopted an effective way to work as a team setting camp and dismantling. We each knew our roles, and it was working.

Collectively, Julie and I have spent over 60 years in the mountains or oceans in various adventure sports and understand resilience. We have the ability to recover quickly from challenges, which is an essential trait for long-distance adventure. Resiliency is the buffer to ward off stress. It also fuels growth and is the catalyst for traveling well together. Those who have resiliency overcome setbacks as they turn failures into learning opportunities to help them adapt to change. Good collaboration supports positive mental health, as effective teamwork can reduce stress and is empowering. Collaboration is all about getting the best possible result through working together, and it’s incredibly rewarding.

Exercise improves subjective mood. Even half an hour of daily exercise has been observed to improve people’s subjective mood and well-being. A meta-analysis of studies relating to mood and physical activity looked specifically at people who engaged in casual physical activity, rather than competitive sport, and found that those who had active lifestyles reported feeling in a better mood and having better overall well-being than those who did not. Given that we all have to get around town, biking to work is one of the easiest ways to integrate 30 minutes of non-competitive physical activity into our daily lives.

I’ll never forget the euphoric dynamics a crew at the firehall would have after a successful rescue or working call where the team functioned at a high level and had a good result in a bad situation. Although wholly different situations, successes as a firefighter and long-distance bikepacker both leave a similar impression on building a positive outlook on what we do and why. The sheer magnitude of the GDMBR ensures you will at some point have adversity to overcome, and doing so can lead to a similar sense of euphoria. Going in with a positive mindset, preparation, and resilience, the journey can be life-altering and healing, much like a pilgrimage.

Energizing and promoting well-being. When stress affects the brain, with its many nerve connections, the rest of the body feels the impact as well. So, it stands to reason that if your body feels better, so does your mind. Exercise and other physical activity produce endorphins—chemicals in the brain that act as natural painkillers—and also improve the ability to sleep, which in turn reduces stress. Meditation, acupuncture, massage therapy, and even breathing deeply can cause your body to produce endorphins. Conventional wisdom holds that a workout of low to moderate intensity makes you feel energized and healthy.

Over the 35 days on the trail, the highlights were endless, only made that much better by our growth from overcoming the lows. Julie and I both suffered from Giardia, likely picked up in one of the many swimming holes. We hid in a dark motel room before making the decision to hitchhike over 200 miles to seek medical attention and hopefully gain enough confidence to leave the luxury of our accommodation after.

During the illness, we changed focus to smaller goals of simply recovering energy to move forward. Despite being in the middle of nowhere, at least we had a motel room. Alex waited a night but reluctantly pushed south solo. Eventually, we gained strength and moved out of Lima, making our way through cattle country and mountainous views toward Jackson. We made it to Togwotee Pass and found an amazing camp spot behind the lodge but had yet another setback. Julie woke to an eye welded shut with an infection and could not ride. We strained for the best options to get to a clinic, and the closest plan was off route to Dubois and then eventually reconnect with the route in Atlantic City. Julie hitched a ride, and I rolled out on the bike for more than 50 miles of mostly downhill to reconnect.

The distraught look on Julie’s face didn’t bear good news. The clinics were closed or booked, so she couldn’t get advice from a doctor. We sat down and discussed a strategy to turn the corner from adversity. We got another motel for the night and searched for possible diagnoses for home treatments. With some help from a pharmacist and warm moist compresses, I started to see a rapid improvement that evening, so in the morning, we pressed forward to Lander. Another 56 miles of mostly elevation loss and a 25-mile-per-hour tailwind toward Ladner were incredible. We were absolutely flying. Occasionally, I’d lean over and yell at Julie over the wind, and with a wink, I reminded her how easy bikepacking was. The truth was, we were still earning our progress.

Lander is a larger town with amazing resupply and bike shops. The shop gave our bikes a quick tune and pointed out some great camping close by. The next morning, we casually departed Lander toward Atlantic City, maybe a little overconfident on the short 30-mile distance. The ride started with the usual tailwind. I saw that our route would eventually switch directions and estimated a cross-tailwind, but I completely overlooked the vertical gain on the day. The wind soon changed, and our progress slowed to a crawl. Highway alerts showed gusts up to 45 miles per hour directly head-on. Ironically, our shortest day on the bike turned into the hardest. The climb had no safe shoulder, and our average speed dropped to about four miles per hour.

Seven hours later, we saw the iconic saloon in Atlantic City. As we were leaning our bikes against the hitching post, I turned around and saw Alex’s dusty plume trail rolling into town about two minutes after us. Considering our split 280 miles ago and 125-mile detour, the odds were staggering, and this perhaps indicated we were back on track.

The Great Basin was the mental crux of the trip. In my eyes, the way to manage the remote crossings is no different than how I would manage risk in the mountains. Looking at the forecast, a rest day would have to wait. Weather models showed a massive storm approaching, giving us a two-day window of favorable conditions to cross the big empty.

We were all in agreement to depart by 6 a.m. There was no better time than now, and despite fatigue, we were feeling the momentum from overcoming the recent setbacks. The climb out of Atlantic City eventually revealed an early morning stunner of a view, but it also put a lump in our throats as we could see what appeared to be the curvature of the Earth. Either way, trepidation now turned to curiosity as we knew we were in for a special two days on the bike. The surface was dry and fast with a sliver of space between the washboard, so we rolled efficiently into the middle of nowhere. I would stop occasionally to take photos and then time-trial back up to Julie and Alex. I enjoyed this yo-yo strategy for getting photos and not holding up the progress.

Off in the distance, we could see storm clouds building, yet the road seemed to turn away just as it appeared we were going to get slammed. We passed through an industrial area that was eerie and out of place. Shortly after that, we took a hard right onto a road that simply made no sense to me. The surface was rocky and ungraded, and progress was slow. I stopped numerous times to double-check the maps. Alex did too. The road was secondary, and it seemed puzzling to leave the perfect surface we’d been following. We could see options to reconnect in about 20 miles that were less likely to produce saddle sores and numb hands.

Shortly after the decision, we saw wild horses, but they sadly had no intention of giving me time to get the camera out. They were absolutely majestic, with the largest stallion clearly leading the herd deeper into the basin away from our intrusion. A little further down the road, I sensed Alex was struggling. He was stopping and looking at his maps more than usual. We collected and had a discussion. He was following Adventure Cycling Association’s maps, which differed from the 2023 race route Julie and I were following.

What I didn’t know was the Divide route wouldn’t go past the A&M Reservoir, a critical water stop. My assumption was wildly inaccurate, and my planning confusion was validated. The reservoir was a highlight I didn’t want us to miss, and our water was on the low side to make it to the Warmsutter resupply. We zoomed in on the Gaia GPS app and found a reroute that appeared reasonable. With self-doubt after my huge navigating oversight, we followed the new dots to the reservoir some 40 miles away. Coincidently, this new reroute was the same distance that Adventure Cycling’s maps suggested, and we felt it was an excellent alternative on roads less likely to encounter the oil rigs hauling their cargo.

Waking to a stunning sunrise on the sandy shores of the reservoir, we filled our bottles and headed off toward building storms. After countless false alarms the day before, I was certain it was going to be another cat-and-mouse game with the thunderclouds. Nevertheless, as we passed over a large, dry culvert under the road, I took note of the potential shelter. Less than two miles later, we made a desperate U-turn away from giant thunderclouds and sheets of rain nipping at our heels. We made it back to that culvert and dove inside. It felt like a sanctuary compared to what was happening to our bikes outside, with powerful flashes and thunderclaps that shook the ground.

We considered the flash flooding potential, but water wasn’t collecting on the surface. Then it dawned on me that we could be sitting on a large conductor. Suddenly, we didn’t know if we should stay or go. Soon the storm passed, and we crawled out of the culvert to a herd of pronghorns bounding off in the distance. Fortunately, we didn’t have the fabled peanut butter mud to deal with as we mounted our bikes.

Eventually, we hit the tarmac toward Rawlins and settled into another ideal motel. As we ate dinner, we discussed the epic ride Lachlan Morton must have been having on his Divide record attempt. We knew he was entering the Basin soon. From there, heading south nearly felt like a parade. The crux was behind us, and all we had to do now was keep moving and maintain the program we’d mostly perfected. Some of the most inspiring scenery and roads were still to come. However, with the feeling of being well-adapted to bikepacking life, we figured there was nothing that would hold us back from arriving in Breckenridge.

The demographics of each state have their own unique feel. We pedaled our bikes past huge cattle drives in Montana and Wyoming. The interest and respect the cowboys gave us were unexpected and incredibly cool. We traveled through endless in-season hunting territory and camped next to jacked-up rigs and gun-toting weekend warriors who were intrigued by our adventure. Colorado delighted us with trail angels providing coolers on their driveways and motorized traffic offering snacks on the road.

Many of the long climbs at elevation were an ideal gradient, and coming from a steep and mountainous coastline didn’t seem all that bad. When we crested the climb at Ute Pass, the Summit County sign marked the end of the last challenge, signifying that our journey was coming to an end. Breckenridge was just off in the distance.

We were elated to see to be so close to the end and overwhelmed looking back on everything we’d encountered. Then something crept in that we weren’t expecting: a little disappointment that this journey would soon be complete. Each day, we experienced some type of “rider high” or endorphins from the combined 35-day, 1,675-mile experience, but today it didn’t appear. It would have to wait for the realization of what we’d just accomplished to sink in.

Instead, we slowed our pace and soft-pedaled the remaining distance. Perhaps we were accustomed to bikepacking life. The medicine of the bike was now very clear.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.