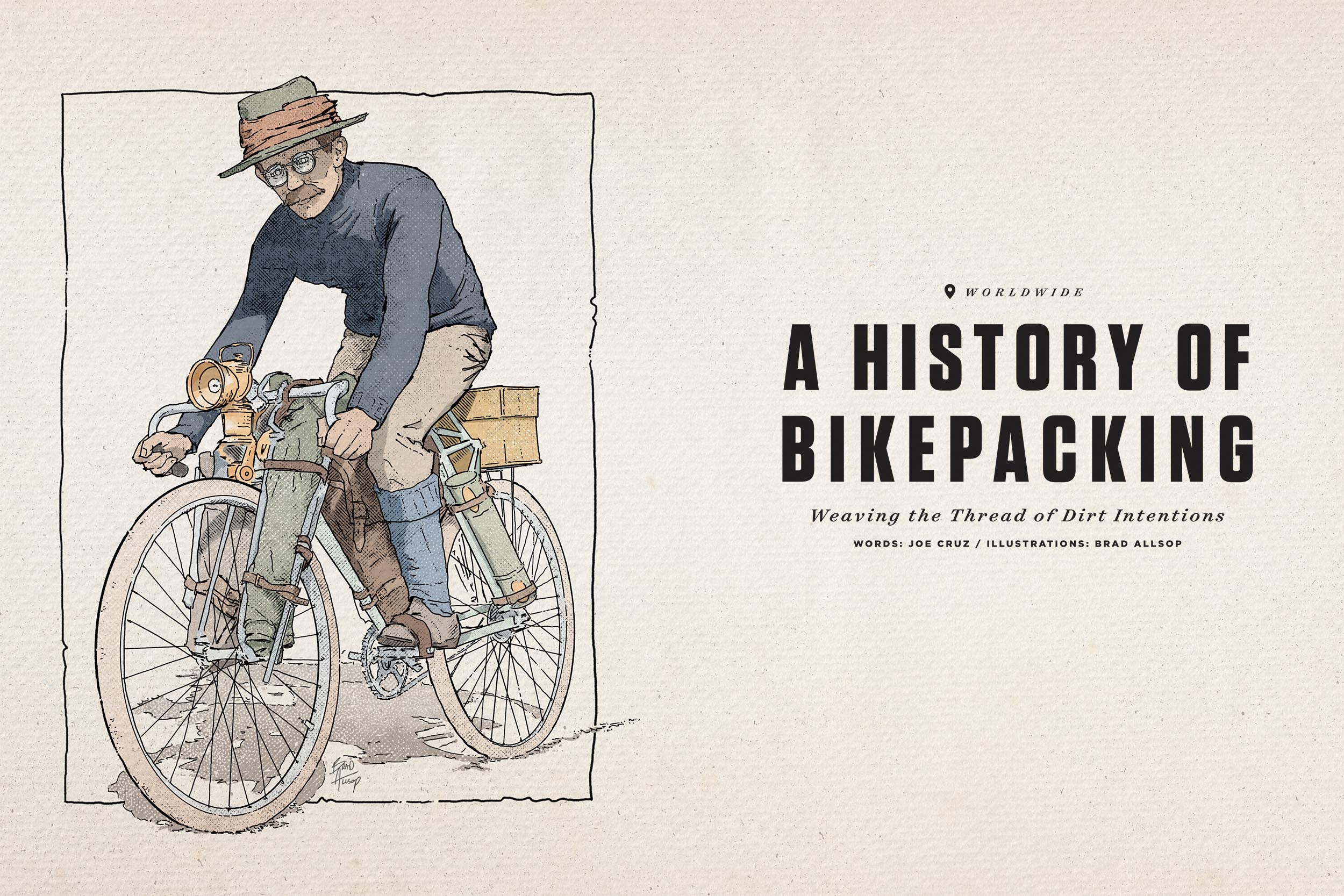

A History of Bikepacking

Originally published in the 10th issue of The Bikepacking Journal, we’re proud to present an expanded version of “A History of Bikepacking” by Joe Cruz. This fascinating piece blends research and storytelling to trace the origins of bikepacking from the late 1800s to today and features a treasure trove of images and illustrations from across the years…

By a defensible reckoning, the history of bikepacking is the history of bicycling itself. If what we mean by “bikepacking” is the idea of heading forth on a bicycle seeking quiet dirt tracks for long rides with a sense of openness while carrying everything one needs for the day or for an overnighter or a journey of many months, then bicycles inspired the imagination from the start in that very way.

In the late 1800s, a trek from one’s hometown incurred expense and challenge. Ranging afar on foot was time-consuming, while a horse or a train would have been expensive and usually demanded coordinating with others. Nor were these modes available to all, and least to women. Bicycles came onto the scene and were an admirable technical achievement, but as a sociocultural force, they were transformative.

In allowing an individual to gaze ahead and pedal there, they created and began to democratize the horizon. That, I think, is at the core of what people mean when they say cycling is freedom. Yes, it’s literal freedom in the sense that the bicycle goes where one steers it to go, and it’s simultaneously a more profound freedom in that it creates dimensional axes that didn’t before exist in ordinary lived time and space. A distance could be crossed on a bicycle with one’s own effort at a pace that hewed close to human perception yet was faster enough to enable inhabiting more lifetimes than was previously attainable. That explains why the bicycle was a catalyst and target for a sense of social upheaval. Individuals had the potential to wander for themselves according to their own curiosity and wonder.

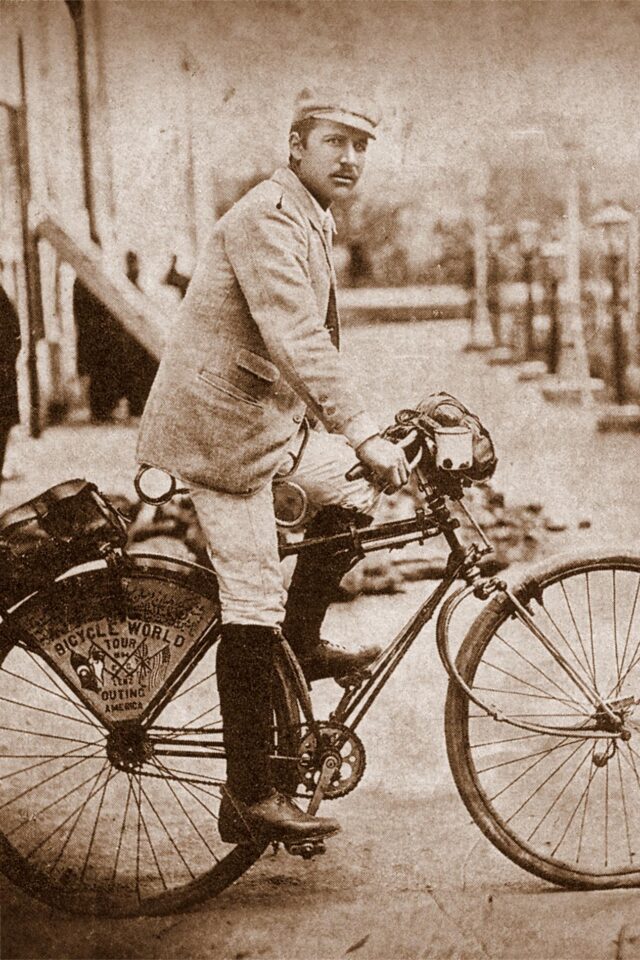

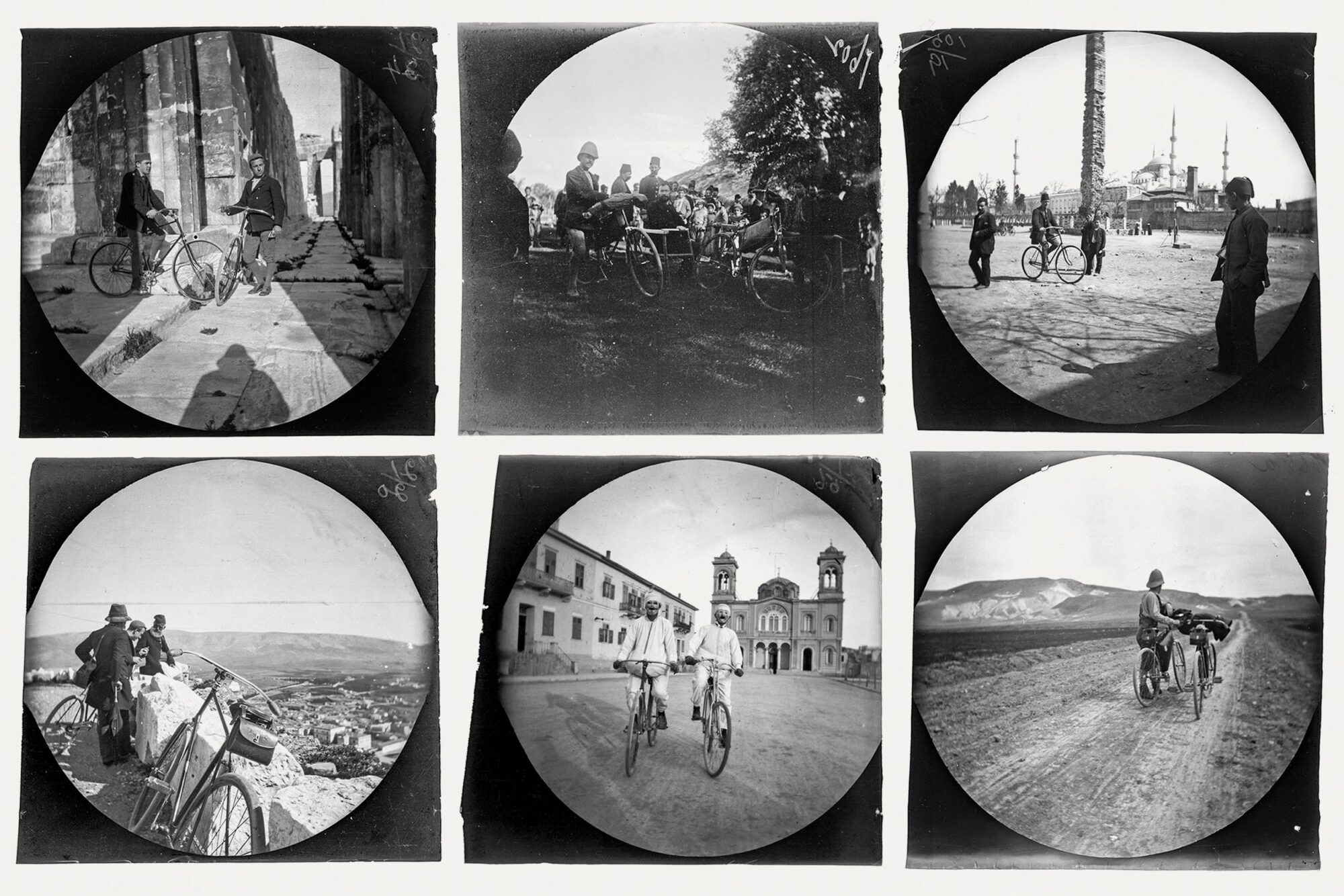

Bicycles concretized uncountable possibilities for movement across landscapes and places, for seeing what could before only be dreamt, for learning about a wider world. And right from the start were conceived the biggest cycling trips. Thomas Stevens, an Englishman living in the United States, set out from San Francisco on a ‘round-the-world pedal on a high-wheeler in 1886. He completed his monumental journey a few years before the ubiquity of safety bicycles, but it was the ascent of bicycles with two equally sized wheels and a rear-wheel chain drive that accelerated and made vivid bicycle travel. Safety bicycles are our bicycles. They don’t merely bear a family resemblance but are nearly the exact machine we ride today.

This beginning of cycling was the era of Thomas Allen and William Sachtleben, who repeated Stevens’s feat (1890-92) but visited places, notably China, that Stevens avoided.1 It was the time of Frank Lenz, who famously went missing during his circumnavigation of the globe, which he started in 1892.2 And of Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, who pedaled around the world in 1894 and was the first woman to become an international sports star.3 She achieved new heights of bikepacking commercial support in that she went by the name Annie Londonderry after being paid $100 USD by one of her sponsors, the Londonderry Lithia Spring Water Company. There was the spectacular 1897 ride of the Black regimen of Buffalo Soldiers from Montana to Missouri, conceived as a demonstration of the strategic possibilities of bicycles.4 The same year, Fanny Bullock Workman and her husband William rode more than 3,700 miles from southern India to the Himalayas.5 The Workmans were already experienced and accomplished riders, having earlier ridden 2,800 miles across Spain.6 These tales merely touch the surface of the long-distance cycling craze that coincided with the coming of the safety bicycle at the end of the 19th century. Bikepacking was recognizably there right from the start.

How, then, are we to make sense of a history of bikepacking that isn’t just the comprehensive, boggling whole of the history of bicycles? Perhaps there’s another way. Stipulate that bikepacking has always existed as long as there have been bicycles. A different approach to the question is, what is bikepacking as pursued with a specific conscious idea of itself?

Logan Watts, the founding editor of BIKEPACKING.com (2012), offers an evocative phrase: he proposes that bikepacking is having a dirt intention on a bicycle.7 What he means is that, to go bikepacking, one departs with a specific mindset. The mindset isn’t composed of specific goals since there can be as many reasons for pedaling further as there are wheelers. The mindset is a broad attitude about what is valuable or meaningful about cycling experiences and how those specific kinds of experiences thrum with resonances of understanding and well-being. Bikepacking is an intention toward the appreciation of landscapes, the chance to interact with strangers, a qualified but genuine self-reliance, a quietude of spirit, an escape from hyper-constructed environments in favor of trees and mountains. Bikepacking is a self-aware contrast with bicycle touring on paved roads or mass-start bicycle racing. Bikepacking is a lucid aesthetic with forthright values, and “dirt” is a metaphor for these values.

Intentions always require enabling potentialities. We need to be able to see the world in a certain way in order to form an intention to be in it with a particular stance. So, the history of bikepacking is the history of those conditions, and that makes it possible to extract specific threads from the overall saga of the bicycle. That’s my aim here. Don’t read this as a comprehensive account of bikepacking, as that would inevitably be fraudulent in its selectiveness. This is instead an invitation to join in unearthing some of the inspirations of our dirt intentions and, ideally, to leave us poised to generate new ones.

PACING TARMAC

Historians mark the 1890s as the first great bicycle boom.8 The legendary tales of a wide world made available come from then. Bicycles were on the minds of everyone in industrialized Western Europe and North America. By around 1920, however, the bicycle was descending from its exalted place in the imagination. Many factors are likely contributors: the natural ebbing of early infatuation, the rise of motorcycles and motor carriages, and—perhaps ironically, given the inventors’ background—the way that the airplane stole the sense of fantasy, even if flying was not in the slightest bit accessible the way cycling was. The role of the bicycle in setting the essential travel ethos of these motorized methods of motion shouldn’t be underestimated.9 Bicycles couldn’t keep up, however. In Europe, bicycles hung on more robustly and longer than in the USA despite the horror and privation of the First World War, yet the siren call of motorized transport was hard to resist, even in the original cycling-mad countries of England and France.

This is not to say that there were no notable bikepacking milestones happening during the first half of the 20th century. Crossings of Australia expressed a new level of rugged determination, given the difficult and remote conditions. Frank Birtles’s exploits started with a ride from Fremantle to Melbourne in 1905, and then extensive ‘round Australia journeying gained him considerable fame and notoriety.10 Tellingly, in 1912, Birtles would shift his attention to automobiles and long-distance driving feats.

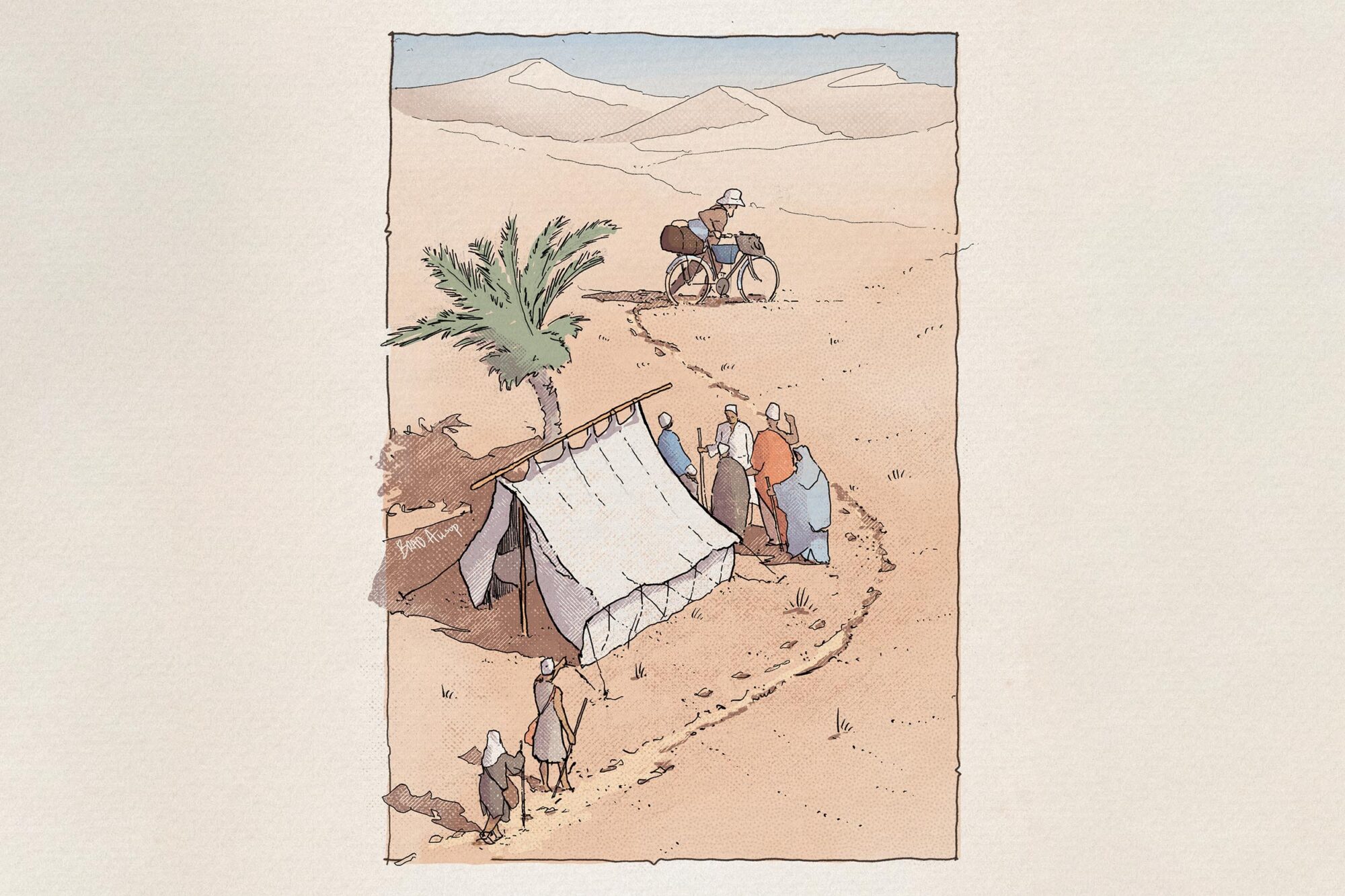

In 1935, Evelyn Hamilton—repeatedly barred from competing in the Tour de France—rode from London to John O’Groats in a little over four days. In 1938, she rode 10,000 miles in 100 days. Fred Birchmore achieved fame for his 1935 ride around the world.11 His bicycle is in the Smithsonian. Also in the 1930s, Kazimierz Nowak from Poland traveled extensively, first in Europe and then in North Africa. His meticulous documentation and striking photography are landmarks of the bicycle travel genre, though they also highlight the othering and exoticizing of the places he visited, implicitly colonialist attitudes.12 That was always present—there’s no reason to believe that Nowak is unusually culpable—and arguably, bikepacking wrestles with the same challenges today.

It’s true, too, that bicycle racing remained an active spectacle in spite of the rise of motorized travel. The 13th Tour de France and the 7th Giro d’Italia were raced mere months after the WWI armistice and continued well after Hitler’s annexation of Austria and the invasion of Poland. Bicycles were powerful sporting symbols, and racing is an indelible aspect of the story of bicycles.

Still, this was a span during which bicycles drifted from their previously central place in technology and culture. In the USA, they were viewed more as children’s toys, while in Europe, they became increasingly invisible as a result of utilitarian familiarity. It wasn’t until the years after the Second World War that bicycles would recover a broader cultural relevance that could gesture at the fever of 50 years prior.

There was a postwar growing sense of leisure and the prosperity of free time in the middle of the 20th century. France saw the heyday of the great constructeurs, bicycle builders who set out to create technically and aesthetically complete functional bicycles with fenders and lights and fittings for long randonées. Such bicycles were also exquisitely suited to more attainable camping trips, and French camping bicycles remain, in the eyes of many, the most beautiful two-wheeled forms ever. This is the era that produced the Rough-Stuff Fellowship in England (1955), a club of riders united by their like-mindedness for riding and carrying their bicycles on farm doubletrack and mountain walking paths.13 Dervla Murphy recorded her incredible exploits on a bicycle, including her 1963 trip from Ireland to India.14 The sense of possibility in riding big distances was once again front and center.

The bicycle resurgence was real and crucial, but it was trailing behind another set of enthusiasms, namely the enthusiasm to pave roads. Paved road building had reached a stride starting in the 1930s in the USA, and in 1956, the Congressional Highway Act provided unprecedented millions of dollars for creating a road network. From the perspective of many cyclists, this was not necessarily unwelcome. At the end of the 19th century, cyclists were the first major political constituency to advocate for better quality roads, and paved ones made for quite excellent cycling.

Probably somewhat to the chagrin of those cyclists, however, once paving roads became widespread, riders more or less immediately came into conflict with car drivers for space and priority on streets and byways. Cycle touring had the interest and material bicycle technology to thrive, but its position was only marginally tenable. Cyclable roads went to many desirable places, but the capacity of these roads and, more importantly, the perception and rhetoric around them, was that they were for cars and trucks.

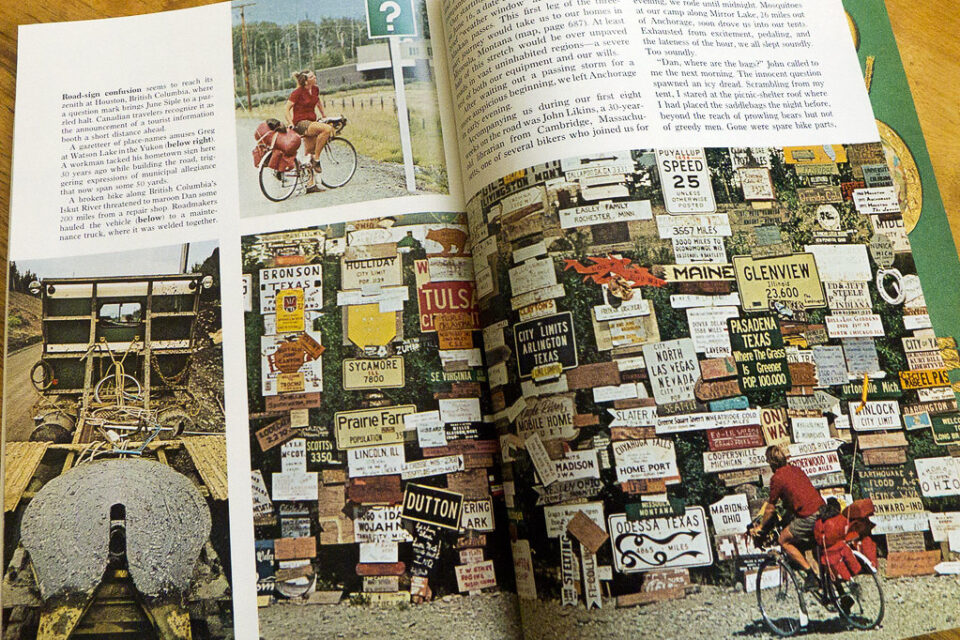

It’s a testament to the appeal of cycling that all disciplines of riding grew in those less-than-ideal conditions. Indeed, by the late 1960s and into the 1970s, bicycling managed to lunge toward a second boom. Touring-wise, this is the time of steel 10-speed bicycles with nylon panniers. It’s the origin of Bikecentennial, which would later become Adventure Cycling Association. Conceived by June and Greg Siple, the audacious Bikecentennial plan was to organize a mass ride across the country in the summer of 1976. The 1970s even originated the word “bikepacking,” which a National Geographic editor coined for a May 1973 article reporting on a trip across Alaska and Canada by the Siples along with Lys and Dan Burden.15 It was the initial leg of their “Hemistour” from Alaska to Ushuaia completed in 1975. Ian Hibell had ridden this journey from south to north from 1971 to 1973,16 and such a ride of the Americas in either direction remains as iconic as any in the world of bikepacking.

Though plenty of people rode their 10-speed bicycles on dirt roads, the imagery of the time referenced open lanes and smooth asphalt. It may not have been a sustainable image, but it provoked and inspired. Around the mid-1970s, it was exciting and meaningful to look at a paper road atlas and trace a finger from end to end across a county or country or continent. Many people gloriously and ambitiously set out on such trips, but a dirt intention hadn’t yet catalyzed.

MOUNTAIN BIKING

Two strands of cycling developed in the late 1970s and 1980s that were essential to modern bikepacking. The first is mountain biking. The second is the stubborn, seemingly reactionary imposition of a road-bike-shaped bicycle onto the landscape of exploration. There’s a pleasing irony and symmetry in the fact that the two strands point 180 degrees away from each other yet would ultimately bend around and rejoin.

Commercially, aesthetically, and socially, mountain bikes arguably rank as the most important set of technical innovations in bicycling since the safety bike itself. From invisibility to commonplace in a matter of a couple of decades, it started to seem as if bicycles simply were mountain bikes. The mythologies and chronicles of the origin of mountain biking seem to foil the chances of a tidy history, but the broad contours are clear enough.17 In the late 1970s, several groups of enthusiastic cyclists pioneered riding their balloon-tire bicycles on steep dirt roads and mountain walking trails. This led to frame building that sought to optimize a bicycle’s handling for more rugged terrain and to fit knobbier tires. All of the knowledge earned in nearly 100 years of bicycle engineering was aimed at the project of making trail-worthy bicycles, with input coming from wherever might help, including motorcycle and BMX technology.

There was also the equally demanding challenge of instigating the production of the essential supporting material like rims and knobbies and strong brakes. This is part of the reason that previous one-off instances of bicycles that are recognizably mountain bikes—John Finley-Scott’s Woodsie in 1953, for example—don’t quite count. Late 1970s mountain bikers had to show off their creations as proofs of the concept to generate a demand so as to be able to manufacture at scale the component innovations required of the sport. Gary Fisher may not be the inventor of the mountain bike, but his company (with co-founder Charlie Kelly) MountainBikes, and then Specialized and a few others, really do deserve credit for making widely available bicycles that rose to a new ambition. All-terrain bikes (ATBs) were a fundamental shift away from accepting the essential morphology and limitations of a road-type bike and were a manufacturing and commercial movement that allowed a new type of bicycling to take root.

The aesthetic side was equally important. Mountain biking was counter-cultural and had a hippie vibe. Riders wore Levi’s jeans and T-shirts and took mid-ride breaks to smoke pot. Less superficially, they had an attitude of finding new paths and viewing the landscape with a presumption of liberty and trespass. That doesn’t mean they weren’t accomplished, fit riders. Racing mountain bikes was there right from the start. In those early days, mountain biking maintained a laudable ambivalence between adrenaline and exploration. The heritage of the Mount Tamalpais Repack racers coexisted with the twinkle-eyed ambition of those who saw mountain bikes as a superior tool for pedaling dirt tracks into the hills.

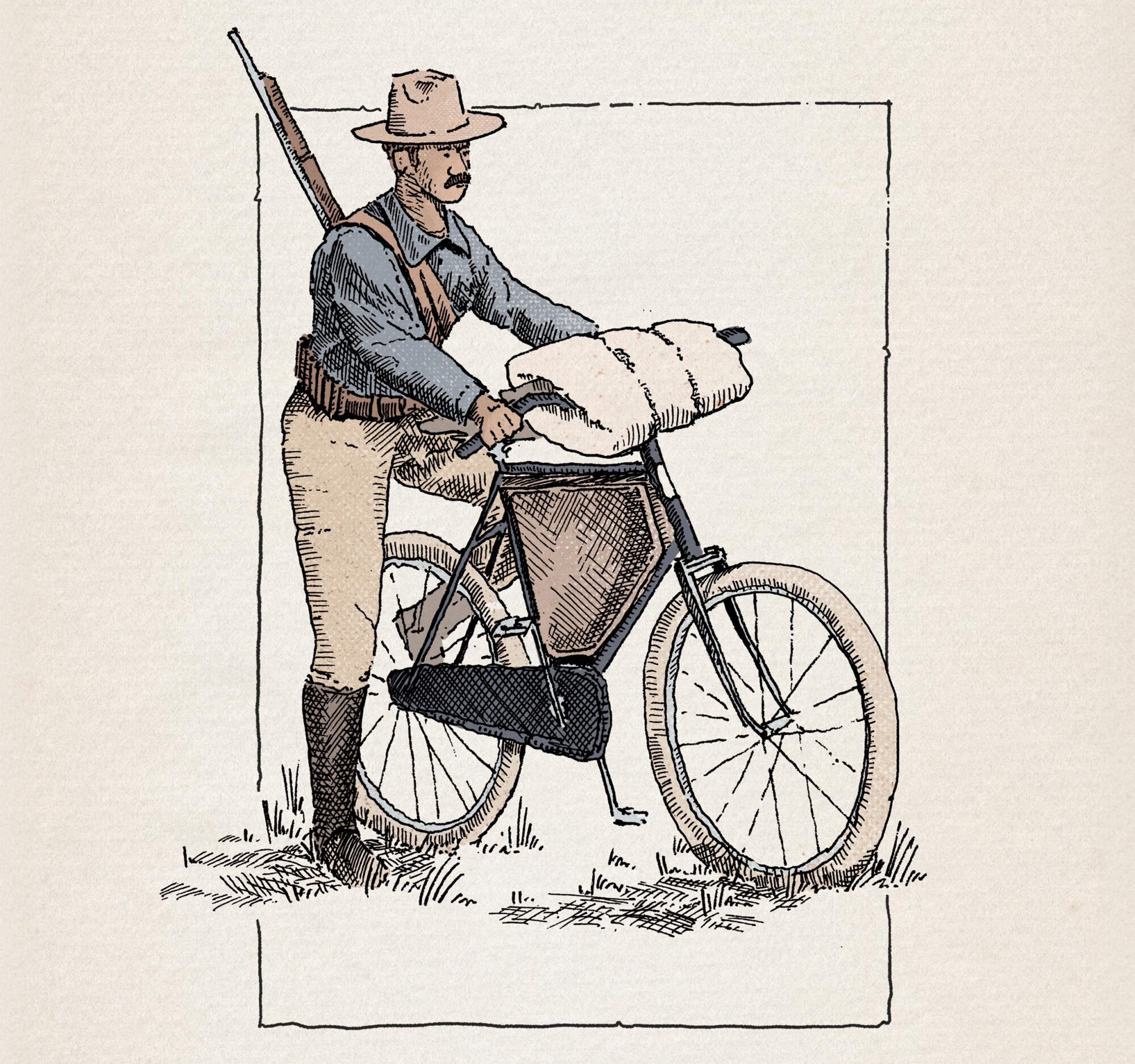

The relevance for bikepacking should be clear enough. Wide gear ranges, flat bars, and knobby tires were a liberation. Within a few years, people pulled off big adventures ranging from Kilimanjaro to the Silk Road to the Balkans on ATBs.18 Mike and Dan Moe from Wyoming rode and hike-a-biked their Diamond Back mountain bikes on the USA’s Continental Divide Trail in 1984, a trip that would serve as inspiration for a dedicated biking route.19 It’s amusing to consider the wild formats then in play. Riders wore rucksacks as if on a hill-walking trip, attached panniers like Bikecentennial road tourists, affixed waxed cotton seat bags supported by rear racks like the Rough-Stuff Fellowship, and even pulled trailers.

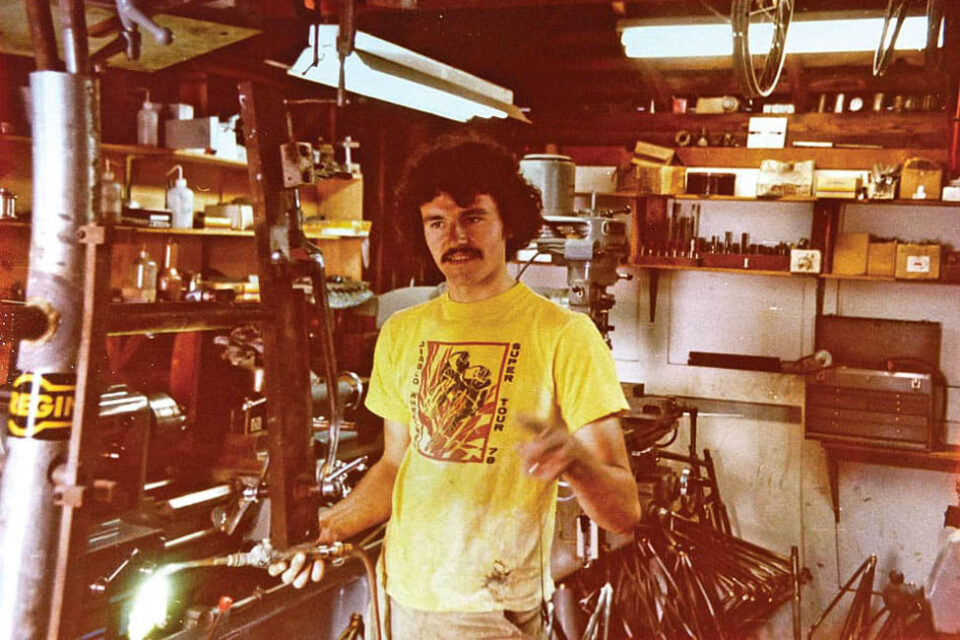

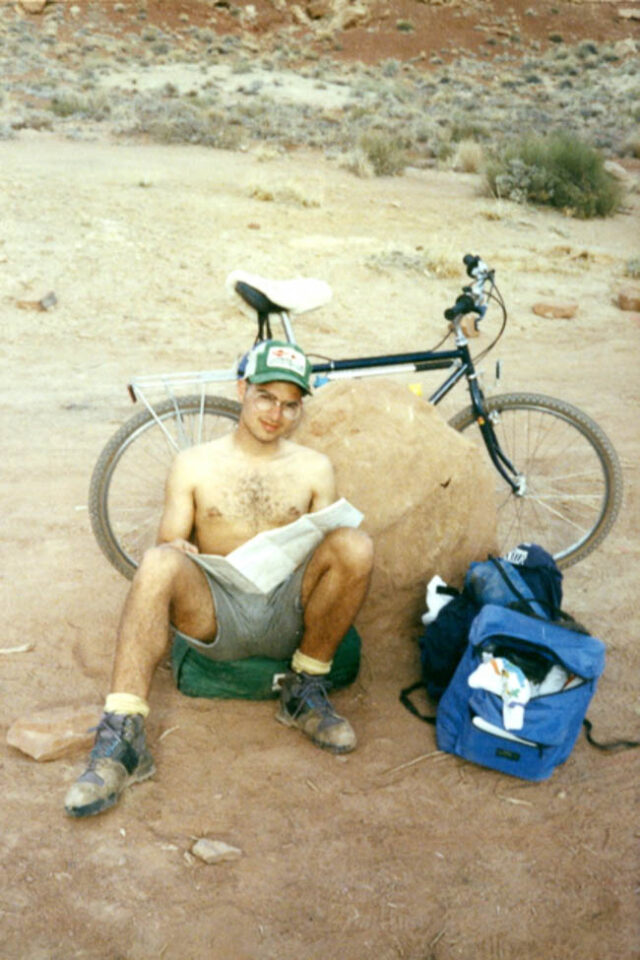

My own early trips were of this era. I had first encountered mountain bikes when I arrived at college and was quickly seduced into day rides in the dells and ridges around campus, sluicing through New England mud wearing cargo shorts, flannel shirts, and gardener’s gloves. At some point, the mechanics at the local bike shop mentioned that they’d read in a magazine about people ATB touring a red dirt off-road vehicle circuit out near Moab in Utah. The sheer legibility and provocation of that image was palpable. At that point, I’d never been on a bike tour, though I’d found the images abstractly compelling. From the sounds of it, one could do the kind of trip that, in my mind, involved a backpack and GORP on a bicycle on the White Rim or Kokopelli’s Trail. I borrowed a rack, panniers, and camping gear and took a train out west during spring break to go bikepacking, though it would be 20 years before I heard it called that.

Mountain bikes exert a heavy influence on 21st-century bikepacking. There was a span in the aughts where in some parts of the world, bikepacking was by definition a mountain biker wearing a technical backpack and taking on the adrenalin-centric endeavor of Colorado Trail-type riding. But I don’t think ATBs are a complete account of the imminence of bikepacking. Throughout the era of the rise of the mountain bike, there remained a parallel world of drop-bar purists who insisted on sticking with their skinny tires for off-piste excursions. They might have seemed like cranks and luddites at the time, but they ultimately played an important role in the current expression of dirt-oriented cycling.

MIXED TERRAIN BEFORE MIXED TERRAIN

Though bicycle touring in the second half of the 20th century implied tarmac, there were always those who sought wilder traces on their drop-bar bikes. Dirt road excursions in Europe and the UK still captured many an imagination. Pass hunting in Japan was in the 1970s and 1980s a lively version of the attitude of taking a well-made touring bike onto tracks that seem more suitable for hiking. The Japanese context is significant as an especially concentrated and self-aware tradition of riding touring bikes on rugged mountain roads that opened high-elevation vistas, with magazines and product lines specifically devoted to the practice.

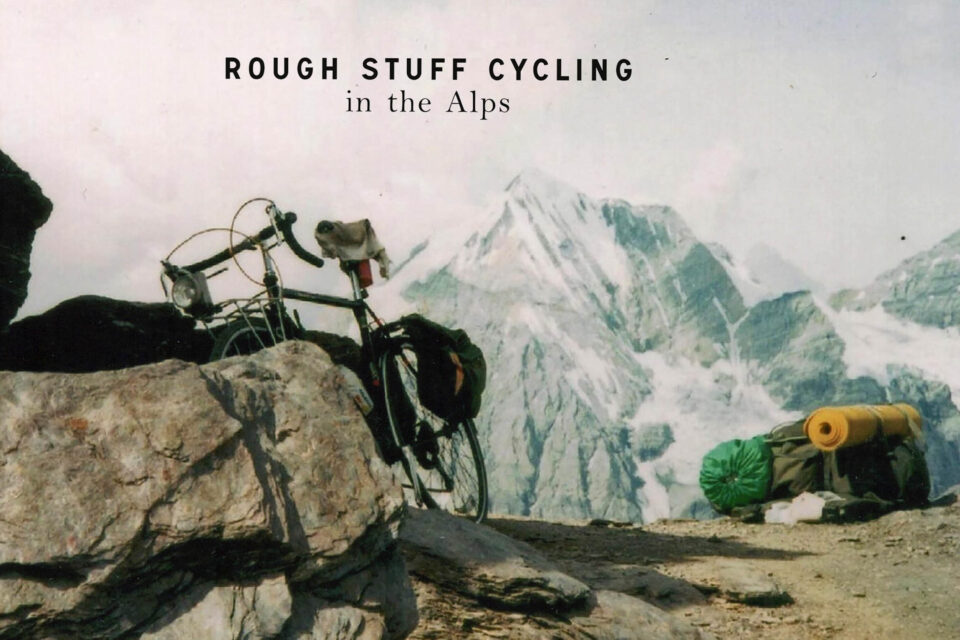

In 1986, cousins Richard and Nicholas Crane achieved a glorious trek from Dhaka, Bangladesh, to the sparse desert in Western China. That latter location they dubbed the “center of the earth” because it is the point most distant from the open ocean. They were veterans of big cycling expeditions on mountain bikes, but for this, they chose bikes with 700c x 35mm tires, what we might call gravel bikes.20 So, riding touring and rando bikes off road didn’t die when mountain bikes came on the scene. Add to that the idea of taking cyclocross bikes off the race course and onto wilder terrain. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, E.D. Clemens circulated among his Rough-Stuff Fellowship friends a series of guides to riding dirt passes in the Alps. These would later be collated and added to by Fred Wright for Rough Stuff Cycling in the Alps (2001). Anne Mustoe’s breathtaking journey around the world on a drop-bar mixte frame must have taken her on an abundance of dirt roads, just as Bernard Magnouloux’s would have, though his drop bars were mounted upside down for comfort!21

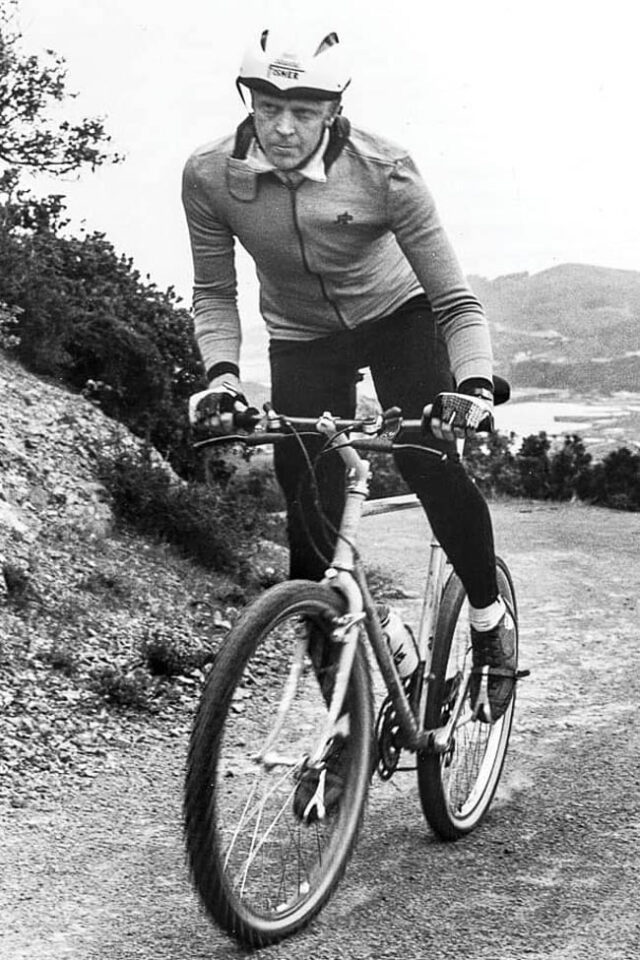

And consider yet another strand of intrepid roadies looking for off-tarmac adventures. In the USA, Jobst Brandt was a fixture of the Northern California roadie community who pursued audacious rides on skinny tires near his home and in Europe during his yearly trips abroad.22 Brandt would gain notoriety by writing the definitive guide to wheel building23 and having a hand in the design of then-groundbreaking Avocet cycling computers. Jobst wasn’t ignorant of mountain bikes and their potential. After all, a young Tom Ritchey was one of the regulars on Jobst’s group rides. He did, however, insist on pushing existing road equipment far into underbiking territory. Chris Kostman of the California Rough Riders offered praises to underbiking that reached a ludicrous shrill. In 1993, he published “Mountain Bikes, Who Needs Them?” in Bicycle Guide. It was hyperbolic and incendiary, proclaiming skill over gear and alleging that he could ride his road bike on any trail faster and better than the average mountain biker. Putting aside the dubiousness of this claim, the spiritual importance of the idea remains.

These are useful placeholders for pre-gravel gravel biking, but it’s plausible to think that there were loads of people all around the world doing the same. There’s a conceptual and cultural significance in riding a bicycle on terrain for which it is suboptimal. It maintains a bridge between the history of cycling, drop bars, elegant mid-20th-century construction, and the poetics of speedy riding. The state of bikepacking 25 years into this century, with the wide range of expressions that increasingly include so-called gravel bikes, owes a direct debt to the holdouts who at the time appeared to be curmudgeons at best.

DIRT ESCAPE

Mountain bikes and off-road drop-bar bikes established the emotional template of what would be bikepacking. The idea was to pedal a big trip or small one riding a dirt-capable bicycle—or having a dirt-forward attitude no matter what the bike—and doing it with curiosity and openness and willingness about landscapes and people and place. Having a dirt intention was not only possible but present. Again, none of it was novel, not the pieces or practices. Hardly anything ever is. Yet the self-consciousness about it, the knowledge sharing, the way individual inspirations and insight get synthesized into shareable lore: That was something new.

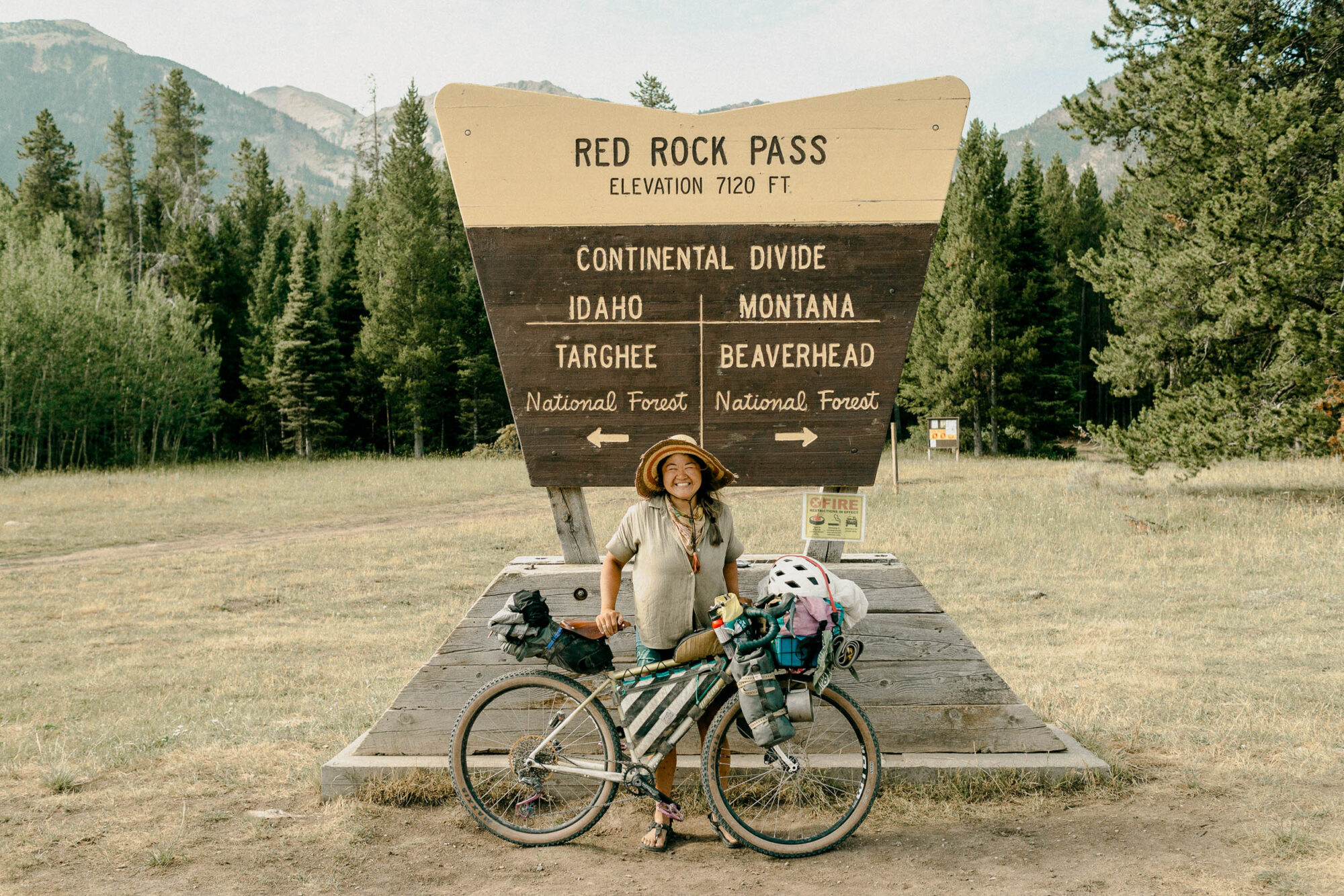

The Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR)—conceived as a dirt trace spanning the USA from its border with Canada in Montana to its border with Mexico in New Mexico—was researched and mapped by Michael McCoy and completed in 1997. The first edition of the guidebook for the route was published in 2000. This work by Adventure Cycling Association is a watershed. It made available the blueprint of how to do something extraordinary, namely how to follow the continental divide on a multi-month journey on a bicycle, seeing vast open spaces but also thereby finding a resonance with the USA’s history, both the glorious parts and the ugly. Actually gathering up the gear and the time off to do it was secondary. It grabbed people by their capacity for fantasy.

It wasn’t long before a race was organized on the route and generated a fan base that avidly followed the action. “Dot watching”—tracking racers online using their GPS-plotted location—was possible because of the right confluence of interest and digital mapping and satellite technology. The Tour Divide race isn’t solely or even mostly about racing and gear and technology, though. What was important was the concretized joy that it could be done. The route served as a metaphorical context within which one could project one’s own cycling. When Jill Homer published Be Brave, Be Strong (2011), she gave voice not only to her moving personal journey but also to an opportunity for catharsis that anyone could aim for.24 The surface of the story was her 2009 Tour Divide race, but the deeper tale was of tenacity, reflection, and raw honesty.

The GDMBR was perhaps the most visible expression of the bikepacking ideal, but that turn-of-the-century era yielded much more, including the Maah Daah Hey Trail (2003) and the Absa Cape Epic racecourse (2004). Within a dozen years, there would be numerous massive rides scouted. Internet sharing and social media undeniably also play a significant role in the origin of bikepacking. With sites like BIKEPACKING.com, riders could share knowledge, admire (or disparage) one another’s equipment, propose new challenges, and therefore solidify a recreational culture around bicycling on dirt tracks. The opportunity for networked reflective self-understanding of bikepacking as something to do finally concretely manifested the dirt intention.

A RETURN TO TRADITIONAL LUGGAGE

These routes and the mass-start events sometimes associated with them pushed the need for better, lighter equipment. It’s in these innovations that we see the more visible expressions of what people associate with bikepacking today. It’s common for people to interpret the origins of bikepacking in terms of the gear used. The spectacle of soft bags strapped hither and thither on a bicycle frame can be jarring and is certainly visually salient. People who grew up seeing touring bikes with panniers affixed to racks can find it tempting to think of that format as “traditional” and to see bikepacking soft bags as new-fangled, or, worse, as one more meaningless way gear manufacturers set out to sell us something.

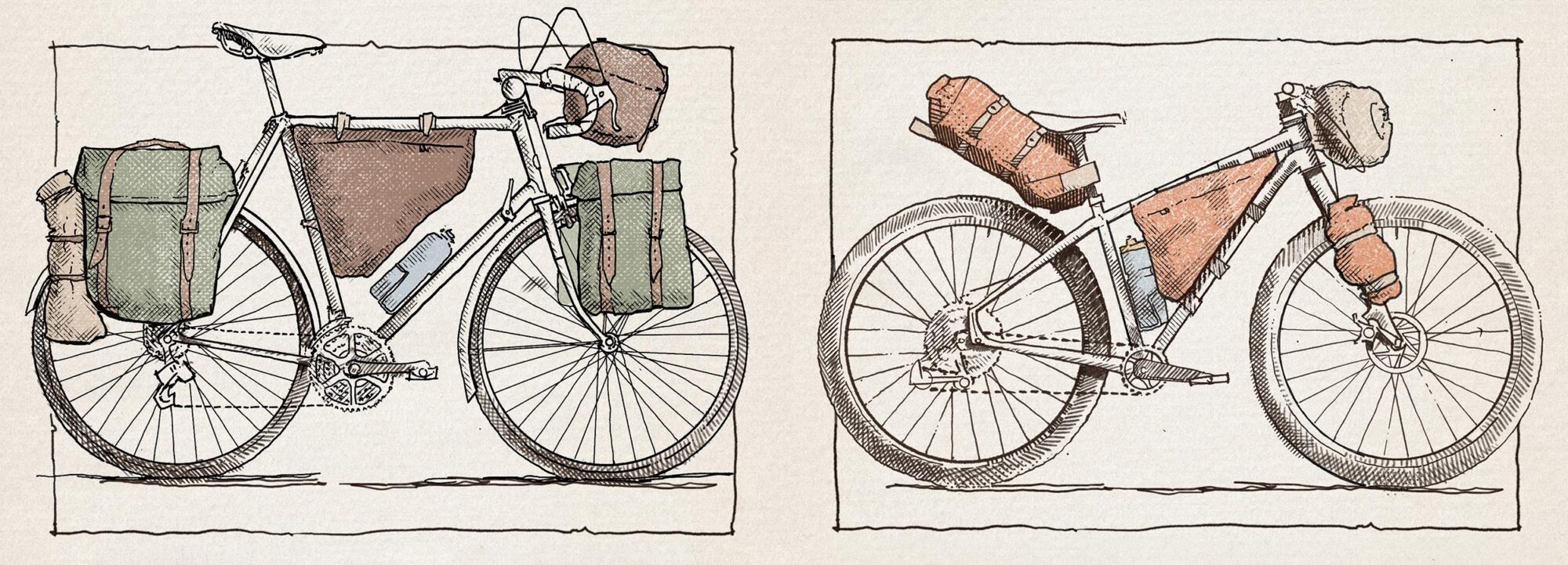

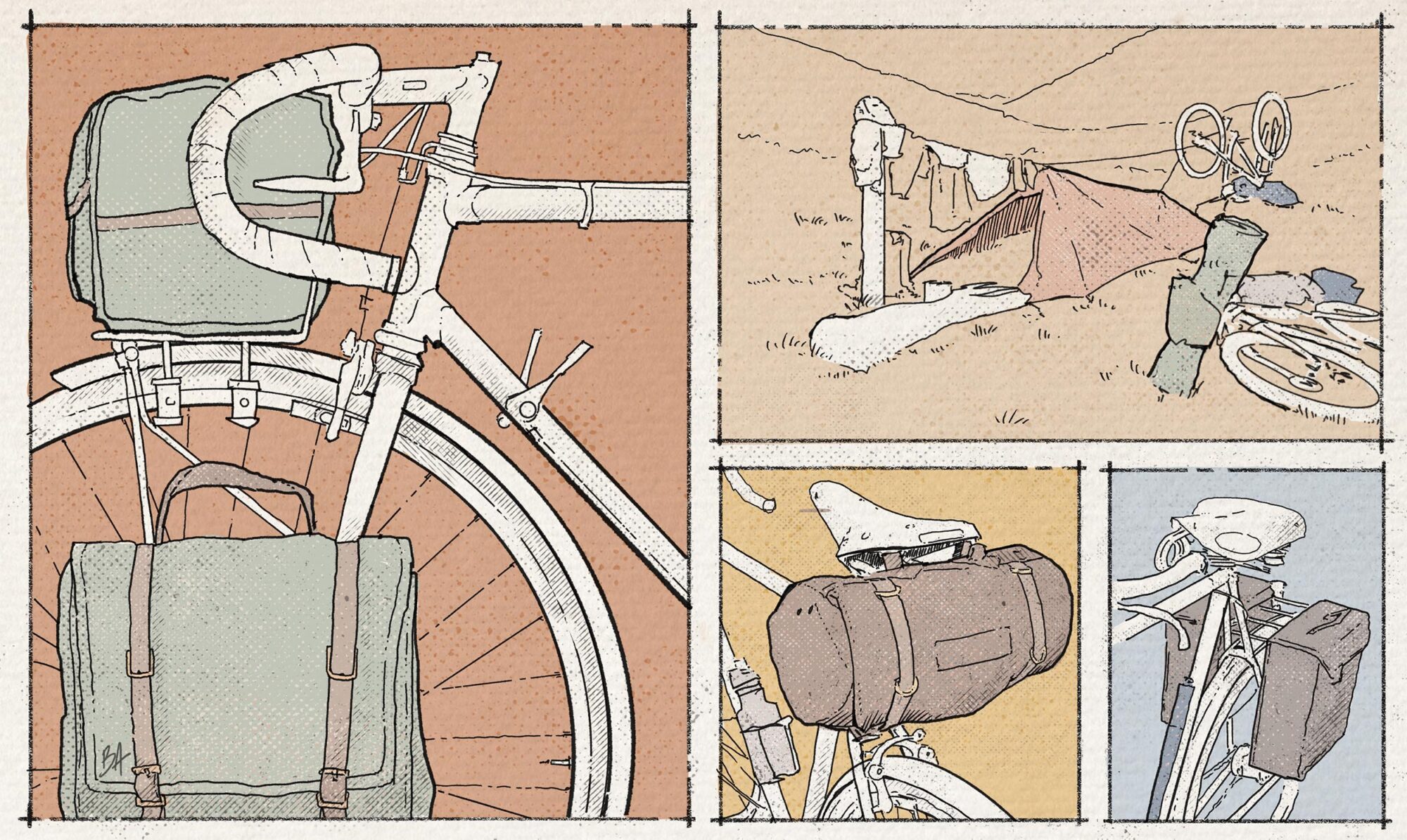

Just to set the record clearly: a bag occupying the space in the main triangle of a bicycle, a roll affixed to the handlebars, and a seat bag without a supporting rack was one of the first formats for carrying supplies on a safety bicycle. This is how Sachtleben and Allen outfitted their bikes for their traverse of the globe,25 as did the Buffalo Soldiers. Paging through the volumes of illustrations and photographs of bicycles from the last decade of the 1800s, these bags are ubiquitous.

Patents for panniers—inspired by horse technology—can be found from the same span. Yet they were vastly less common than a strapped bag setup, and it isn’t until the postwar period that panniers come to dominate the imagery of luggage-carrying capacity on bicycles. Once panniers took over, their popularity was overwhelming. Eugene Sloane’s 1970 Complete Book of Bicycling only talks about panniers in the bicycle camping chapter.26 In it, frame bags have completely disappeared from the carrying arsenal of bicyclists. And this persists through to the “Carrying Your Gear” section in Stephen Lord’s 2006 Adventure Cycle-Touring Handbook.27 No mention is made of the possibility of soft bags that strap onto the bike. The only distant second choice behind panniers is a trailer. Ten years later, in the 2015 third edition (this time with extensive revisions by Neil and Harriet Pike), bikepacking bags stand co-equal with panniers and trailers as a viable gear-carrying method.28 In less than a decade, the traditional soft bags of dirt riding regained pride of place.

They have relatively limited capacity, but bikepacking bags earn a massive advantage in that the elastic properties of the straps make them much more reliable against breaking than a rack-based system. This can be difficult to make sense of in today’s market of well-built racks, but that is a recent phenomenon. There was a time when breaking the weld on a rack or shearing the bolts that affixed the rack to the bike frame was more or less inevitable if one toured on rugged terrain.

Bikepacking bags can also pay off in terms of riding narrow singletrack or walking alongside a bicycle while pushing it up a hike-a-bike section. A bag sewn to the dimensions of the main triangle of a bicycle is fairly straightforward, and both commercial and homemade versions have been available throughout the history of bicycles. Eric Parsons, the founder of Revelate Designs, reports that in 2002, he had a frame bag made because he’d seen one on someone else’s bike at Alaska’s Iditarod. He was dissatisfied with what was available for touring and was seeking new carrying solutions. A few years later, in 2006, Jeff Boatman sewed and marketed a carefully engineered seat bag under his company, Carousel Design Works. Eric was working on one too. The last traditional component, the front roll, was easy to improvise by rolling up one’s sleeping bag and tent in the sleeping pad and strapping it on. But better harness-type solutions would soon be made available. By 2007, Jay Petervary used the rackless bag arrangement to win and set the record for the Tour Divide.

Carrying innovations weren’t the only notable inputs to what we think of as bikepacking these days. The movement toward wider tires has been a significant development in making bikepacking bikes more capable and comfortable. On the more ATB side of the bikepacking spectrum, this includes fat bikes with tires of up to a whopping five inches wide. They might only see use in the most specialized expedition contexts, but the still substantial three-inch “plus” tires of contemporary bikes remain central.

In 2011, I rode the length of South America. The contrast to a year-long ride in Asia I had taken in 2007 was stark. In the earlier trip, I had pulled a trailer behind a full-suspension mountain bike. My reasoning was that I was going to do a number of mountain bike races in India and Nepal, and I wanted the most convenient way of carrying gear that wouldn’t interfere with the race functionality of my bicycle. By 2011, my goals and concept for a months-long dirt trip had changed so much that I ended up making two fateful decisions about equipment.

The first decision was to ride a fat bike, the Surly Pugsley that I used for winter riding but was seeing more and more as not only a viable but an ideal year-round bicycle. I was emboldened by having done a summer fat bike tour in Alaska the year before and by acquaintances like Jacob, Goat, and Sean from the Riding the Spine project from 2006 to 2010.29 The second decision was to abandon the racks and panniers I had tested and instead use Revelate soft bags. In addition to all the advantages of the rackless setup enumerated above, the all-in weight difference was 11 pounds (5 kilograms). I was pushing my envelope of comfort for expedition-style light packing.

On the drop-bar bicycle side, there has been a general movement toward wider tires, even for milder dirt roads or mixed-terrain routes. An important instigator here has been the rise of gravel racing and gravel riding in general. The drop-bar apologists who held out against mountain bikes have, in some sense, been vindicated, though by now, the hybridization of bicycle forms is very far along. And there is also the effort to create more ergonomic and versatile bars. These alternative bars often reflect designs that have existed for a long time, but bikepacking has created a new context for them.

BIKEPACKING NOW

It would be misleading to claim that the rackless bikepacking setup somehow is a necessary or sufficient condition for bikepacking. Likewise, there are no rules on the kind of bicycle that one might use to go bikepacking. In the first quarter of the 21st century, there has been a satisfying proliferation of formats and designs for pursuing dirt intentions.

Bikepacking has changed in even its short, self-conscious history. It has moved away from its full-suspension mountain bike-centric phase to one that emphasizes more accessible dirt touring. This has enabled a much wider range of personal expression—mountain biking fashion and sensibility were quite insular 20 years ago—and ways to incorporate other interests into a bikepacking trip. Photography has been a constant in the history of bicycles, but we can now add fishing, packrafting, and stopping at craft breweries to the repertoire, to name a few.

More substantively, an important element of the crystallization of bikepacking was the increase of new kinds of voices in the lore of dirt pedaling. David Hale Sylvester’s Traveling at the Speed of Life (2012), for example, exemplifies this more inclusive storytelling. Arguably the most famous bikepacking racer in the world right now is Lael Wilcox, a gay woman from Alaska. And some of the most exciting trips and routes are being reported by riders and clubs in India and Thailand and Colombia.

Here is a thought that gives me a positive feeling: If we arbitrarily but not without grounds mark 1890 as the beginning of cycling as we know it, it persisted for about 60 years on dirt before paved roads took over. After that, from recreation to fitness to racing to touring, bicycles were asphalt coinhabitants with cars in the popular imagination. And this is where they remained for another 60 years, marked at 2010. That symmetrical span of time on each side of dirt and tarmac has a certain sense of potential about it.

Bikepacking emerged at a balance point, and however we take it, whatever we do, is correct and open to our sense of invention and ideation. Bikepacking is loading up a bicycle with lunch for a picnic and an afternoon of reading on a blanket in a nearby park. It’s packing for an open-ended trip far from home over mountains and through cultural stories not your own. It’s a long weekend with two nights spent looking up through the crowns of trees to the Milky Way before falling asleep. Bikepacking is riding a bicycle mostly on dirt, sometimes on the inevitable asphalt, sometimes on a track where only feet or two wheels can go. If you had a bicycle that was made in 1890 and was still in running condition, you could most assuredly bikepack on that. More realistically, you can ride your dirt-capable drop-bar bike or mountain bike or bike with a basket or bike with panniers or bike with a frame bag and handlebar roll, or just about any bike, really, and participate in a future history of bikepacking.30

Find all 30 works cited in this piece here.

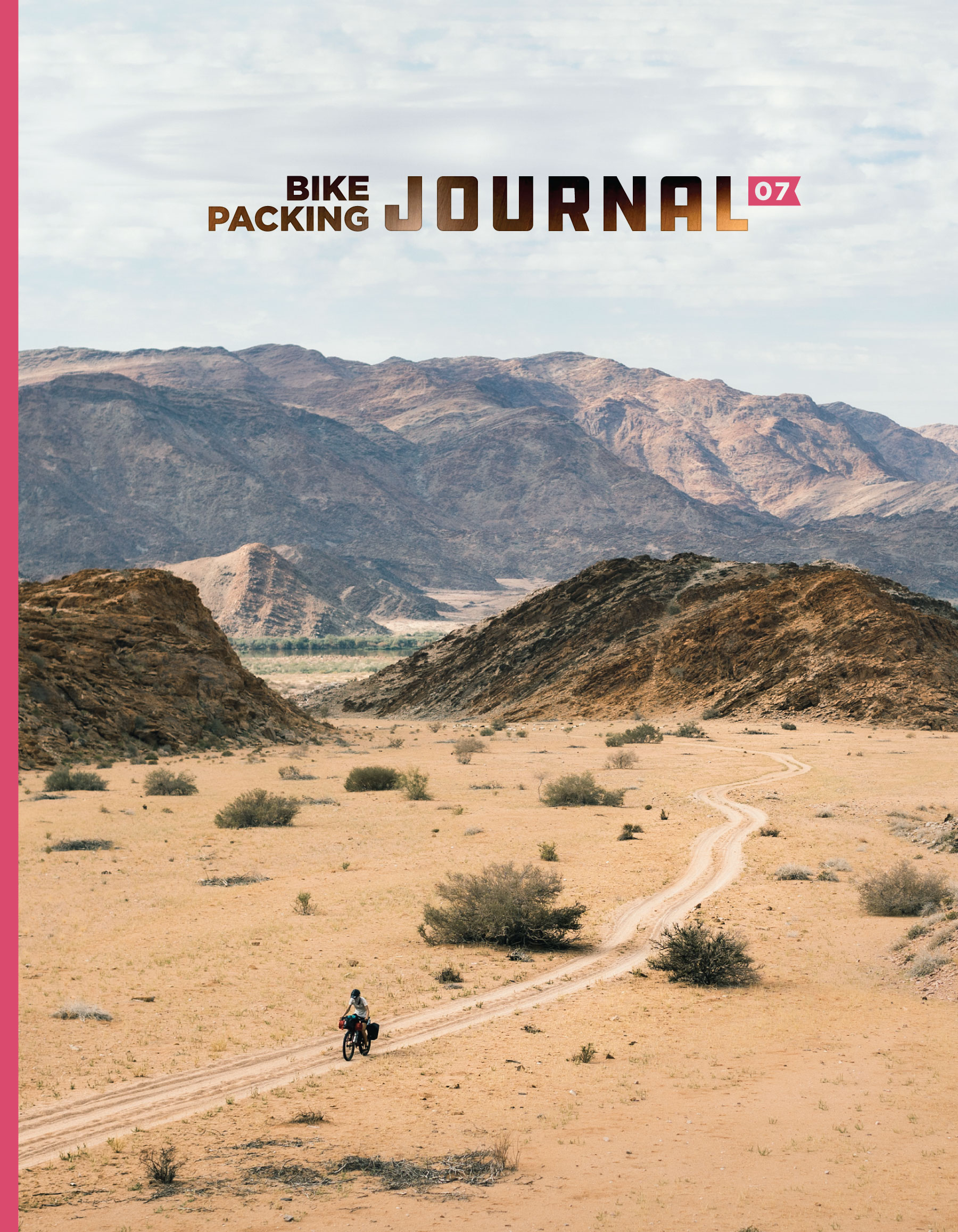

Interested in more stories like this one? Enjoy inspiring writing and breathtaking photographs, all in the full glory of print!

- Twice yearly – New issues are released in April and October of each year.

- Free shipping – Shipping is on us, anywhere in the world.

- Carefully crafted – We've worked hard to create something beautiful and lasting.

- Limited edition – We print one copy for each of our members, and not many beyond that.

- Only in print – There's nothing quite like savoring stories and images on paper.

- Truly independent – This project wouldn't be possible without our members.

- Member Support – Sustains this website and all the content we publish.