A Day with Paul Price of Paul Component Engineering

Last month, Evan Christenson stopped by Paul Component Engineering in Chico, California, to spend time with founder Paul Price and learn about the celebrated company he built from his garage more than three decades ago. Find a look inside the lively manufacturing space and get to know Paul and the fascinating story of his hand-machined parts empire here…

PUBLISHED Jun 28, 2022

You’d think having your name firmly stamped into the annals of cycling history would make someone a bit gruff or floating in space and dancing through the office, but even acknowledging it is hard to get Paul to do. “Nooo, no, it’s not iconic. No, seriously. Okay, maybe.”

Paul Price, turning 60 this year, with his grease-stained shirt and tufts of grey hair, fuzzy felt hat, and big leather boots, has built a company on the outskirts of Chico that has sent waves around the bicycle world in the last 33 years. It now does millions of dollars in business a year using American materials and manufacturing and is still swimming against the tidal wave of overseas production. Paul, the mastermind behind his namesake company, never expected things to be the way they are today. “Pre-COVID, it was already more than I ever imagined, honestly.” Then the pandemic hit, and everything exploded.

Paul’s father was a nuclear engineer working under Reagan and personally set off one of the largest ever nuclear explosions. With big academic shoes to fill, they made him go to college. “I went to college, partied too hard, and flunked out, so that showed them.” He returned home to the Bay Area to pump gas when an old classmate drove up in a new Corvette. “And there I was, pumping his gas, and man… that didn’t feel good.” So, he went back to school.

Paul was always a tinkerer, playing with saws and working in shops, but it wasn’t until college he started getting into designing things. Coincidentally, his rising interest in engineering paralleled his first dabbling in mountain biking, just around the corner in Marin. “I rode those first mountain bikes, and they were just so bad.”

His parents weren’t outside people, “So that added to it. It was rebellious, riding out into the mountains. They had no idea what I was doing.” He started developing parts to make them better, brakes mainly, each solving one small problem at a time. “Joe Breezer came over in college one time, and I spread my blueprints out on the floor, and he sat there and looked at them with me. That really meant the world to me. He was my hero.”

Paul finally graduated from Sacramento State with a degree in mechanical engineering, just a few years before computers became part of the curriculum. He got a job designing tooling in San Mateo and asked his longtime girlfriend to marry him. She said yes, but right before the wedding, she walked out. Paul took it as the final kick in the pants, quit his job, moved to Chico, bought a house for $49,000, and started Paul Components out of his garage in the wake of the heartbreak.

“Those early days, they were magic. I didn’t know if we were ever going to make it. I ate a lot of Top Ramen back then. We had shipping and assembly in my living room, tooling in the garage, and a polisher vibrating all day in the closet. I had to cut a hole in the floor so it didn’t shake the house apart.”

Five people took the first Paul Designs mainstream: first axles, then mostly brakes and levers, almost all anodized purple. “Back then, you could take anything, anodize it purple, and everyone would buy it. My company certainly made some crap back in the day.” Paul started branching out, making seatposts and stems, until he came out with the eight-speed rear derailleur. “And that just rocked my world. I was on the cover of magazines. I was like… famous.”

And then, as fast as the world came together for him, it fell apart. “Shimano, this multi-billion dollar company, came out with XTR in 1991, and that ended us. We had to really grow up fast. I laid off everyone but one person, and we had to weather the storm.”

It wasn’t until the early 2000s that Paul started to find his way again. The anodized fad had died off, and most components being bought were made overseas. “It was changing so fast. 7 speed. 8 speed. 9 speed. There were some people who just said ‘Screw this…’ and started riding single speeds. They were rebelling against this rapid pace of change. I made the first single speed hub mountain bike, and that was what changed it all.”

Paul Components finally found their new niche, and they started gathering momentum. In 2005, they moved from a small rented shop space to this new shop, just down the street. “We immediately had an addition put on, and we outgrew it within a year.” The unassuming space, an old Texaco petroleum distributor, lies on a main artery of Chico, and to passers-by, it’s kinda dumpy. “We like it that way. I don’t like unexpected visitors.”

Paul Components was doing well as a business. Paul was designing and building the parts he’s always wanted to build. They had a dozen employees. They had carved out a small corner of the market and planted themselves firmly in it. Their stuff isn’t the lightest, and it’s not always on-trend. It’s all milled out of aluminum, and the design is strictly utilitarian. But their stuff lasts, and eventually, as their reputation got around, they let the market come to them.

“When COVID hit, we were doing pretty well. We had, luckily, a huge inventory. We sent everyone home and were unsure if we would even survive the pandemic. About a week into it, I got a call from an employee saying, ‘I’m like really overwhelmed right now. Everyone wants to buy bike parts for some reason.’ People were laying their groceries out in the sun so the virus would be killed back then, but we brought a couple of people in, kept them all separated in the office, I got everyone a porta-potty, and we got to work.”

Paul was uniquely positioned to capitalize on the cycling boom during COVID. Unlike most manufacturers, who were struggling to get parts from their factories overseas to fill orders, Paul ramped up production and watched a record number of parts fly off the shelves, seeing a growth of 60% during the pandemic.

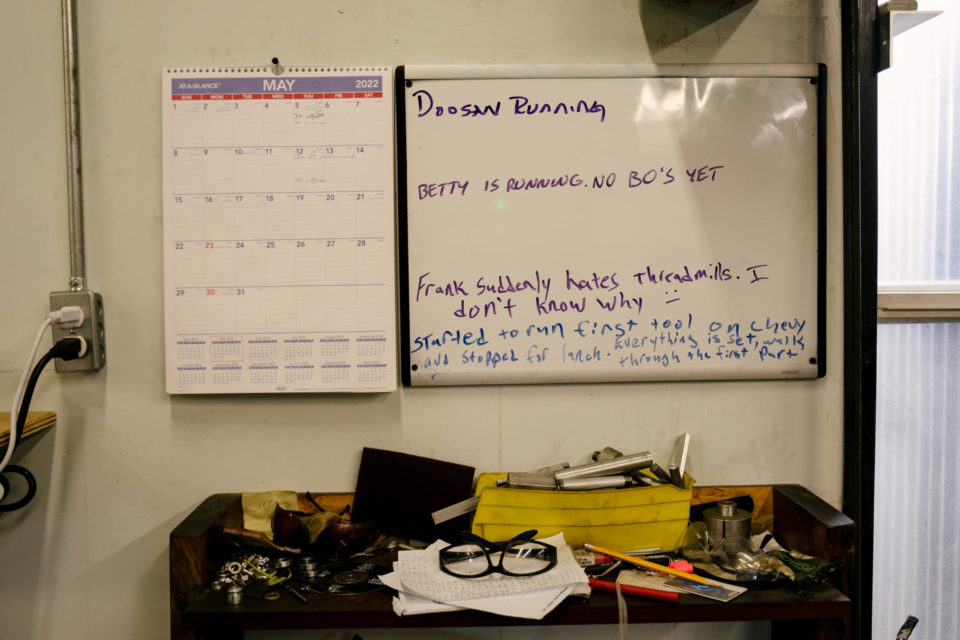

Recently, they added a new machine, a $250,000 fully automated mill/lathe from Doosan. Bars of aluminum go in one end, and a collection bucket is filled with finished parts on the other end. Their other machines, six in total, all require some higher level of interaction to keep them going, but still, they run seven days a week. The Doosan runs 24 hours a day, and the rest of the machines have three shifts, meaning they run about 20 hours a day. Paul is soon adding yet another addition to their small warehouse and immediately adding two more Doosans, hoping to add production capacity to keep up with rising demand. “Our biggest issue now is finding skilled workers who know how to operate these machines.”

It’s a hectic workshop, surprisingly clean, with a jazz cover of Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit playing over the whirring drone of machinery. Old bikes hang from the roof, most adorned with vintage Paul Components bits that would all fetch thousands of dollars of eBay. The layout is pretty simple. Bars of aluminum, made in America largely from recycled beer cans, gather outside where they’re delivered. They come in one door where they’re cut into the right length, categorized, and then brought into the production room, where they go into any one of the machines for milling and/or lathing. Once cut, they’re sanded in the finishing room, then either brought down the street to Ted, who hand polishes them, brought up the street to the anodizer, or straight to assembly in the warehouse.

Ten bars of aluminum put together are longer than the entire warehouse, but in that space, one bar comes in one door, and a dozen finished parts go out the other. They go through about 2,000 pounds of aluminum per week, half of which is machined away and sent back to recycling.

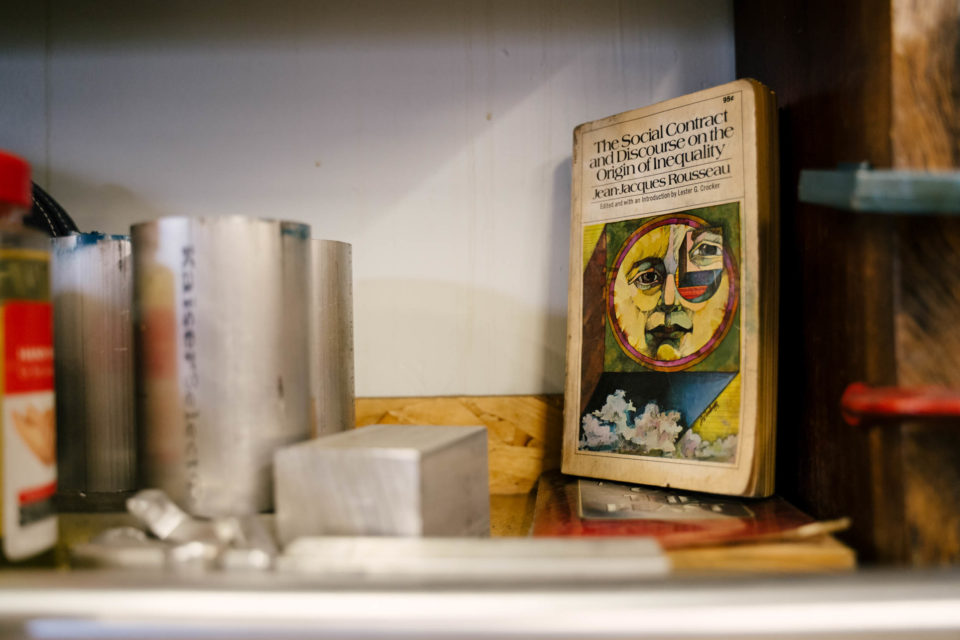

In the final room, separated from the rest of the factory, the size of the first garage the whole company was built out of, is Paul’s playroom. In it are several old machines, from the 1950s and 60s mainly, all American, all analog. Paul comes here to prototype, and he often stays late.

The contrast between these machines, $500 dead relics of American manufacturing found on Craigslist, and the state-of-the-art machinery next door is symbolic of the company today. Paul Components is invested in the future but still playing in the past. “I’m not even allowed to touch the new machines,” Paul chuckles.

He’s happy in here, still screwing around, building things he thinks would make riding a bike a better experience. “Yeah, some people have mentioned moving my production overseas, but why would I do that?” He’s showing me a circular mill from the 1960s, built by Kearney & Trecker. You wind a crank to change the diameter of the circle. It moves like a bank vault, the motor makes a decisive whisper, and Paul sprays WD-40 on it to cool the bit. “I like to make things. I couldn’t do this overseas.”

We take the dune buggy to dinner at the Sierra Nevada Brewery just down the street. He shows me the custom bike rack mounts he machined to mount bikes on top. While there, two people come up to introduce themselves, offer suggestions, and thank him for the excellent customer service during the pandemic. Paul is uncomfortable being recognized in public, a bit awkward, but he’s getting used to it. “Two in one day is also a little out of the ordinary, but I can’t really go to bike shows anymore and just enjoy them.”

Moving forward, he sees his role as increasingly hands-off, working to prototype the parts he wants to bring to market and hiring a manager to keep everything else in line. “The company is finally to a point where I can go away for a month and come back and everything is okay.” Recently, he bought a van, and he wants to go ride his bike.

He’s uncomfortable admitting it, but the pandemic times have been good to Paul in many ways. They’ve given his company a big push to make it sail. He feels stable and secure now, and he even met his new fiancé amid the madness of the past two years. Looking further back, he’s proud of the products he’s made, especially all the ones that are still being ridden. “There’s a quality vibe machined into your parts,” I mention, my mouth full of fries, still buzzing from all the noise in the shop earlier.

“That’s what I’m most proud of,” says Paul.

Related Content

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.