Mud and Blood

Share This

When Paul Kalifatidi’s sunny solo bikepacking journey through Utah’s Canyon Country took several turns for the worse, he found salvation in the most unexpected of places. Read his story of literally and figuratively digging deep to brave waist-deep snow and bike-stopping mud in hopes of sublime riding just around the next corner here…

Words and photos by Paul Kalifatidi

Jess and Eli dropped me off on the side of the highway in a parking lot next to a cattle grate. There are lots of those in this part of the country—steppes and terraces and cattle grates. Mexican Hat has them in spades. The namesake of the town, the sombrero-like rock structure, was perched above the San Juan River not far away. Jess and Eli took photos and danced to music I can’t quite remember. I was too busy strapping my bags—laden with Idahoan potatoes, salmon packets, and Snickers bars—to my bike to join in the antics. Questions about what my 190-mile route had in store for me swirled in my head.

Like everyone else, I’d spent the past year mostly inside and mostly local. I’m part of that wave of people who found biking during that time. I’d already been bikepacking and had a great rig, but riding wasn’t my primary focus until COVID hit. Over the course of the pandemic, it became my obsession. Being unable to travel for my usual focus, rock climbing, had made me look for other avenues of exploration. Minneapolis is home to an incredible bike scene. I dove in headfirst. Online school and minimal work opportunities provided me with ample time to ride. The network of trails paralleling the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers became my escape. My roommates and I set a metronome of damn-near-daily river bottom laps. Bike repairs occurred just as frequently.

I grew restless. Most did. I desired the discovery and self-exploration that seem to happen best for me in places far from home. Utah wasn’t new; I spent every spring break there, but it was a frequent catalyst for what I sought. My first multi-pitch, my first epic, my first “prepping of the ganj”, my first road trip, my first extended trip as a guide—the Utah desert has all of those firsts. The memories are potent, and I was looking to make more.

I really wasn’t sure what to expect on this trip. I was bull-headed and tired of mind-numbing school work, being inside, and feeling mundane. I was eager for whatever was waiting for me in the 90-degree lowlands, shady hills, endless climbs, and 9,000-foot prairies. I told Jess and Eli that I was planning on meeting them in Indian Creek the following night, aiming to ride 60 miles that day and the rest tomorrow. It was a lofty goal, so I packed food for three days. I told them that if I didn’t show up until the day after, they shouldn’t worry. I had a Spot beacon and could talk to my emergency contact (hey, Mom).

The first 35 miles went by smoothly, it was mostly rolling hills of gravel road and two-track. Camper vans and cows kept me company while horses threw snorts of disdain my way. They didn’t appreciate my struggle through their barbed-wire gates. I ran into an unfortunate mechanical shortly after starting: one of the alloy bolts holding my bottle cage to my fork had snapped and spilled my water all over the desert. I didn’t notice until I stopped for some photos as my handlebar bag obscured the view of water steadily dripping from my bottle. A zip tie and I was off. I ended up needing that water dearly as I pretty much ran out about 20 miles from camp. It was far hotter than expected, and my body wasn’t used to the heat quite yet. It was still prime winter riding back home in Minnesota.

There were two potential water sources en route. Both were dry. I didn’t pee at all that day. Twenty miles of half-walk-half-ride sandy road finished with a punchy highway climb through a slot in a cliff band. I have a vivid memory of pulling over the crest and exclaiming with exuberance at the beautiful downhill before me, only to be slammed in the face by the biggest gust of wind I have ever experienced on a bike. The descent was Type 2 fun at its finest. Even now, I’m feeling my heart quicken at the thought of barreling along that cliff band while battling the wind.

That day was the thirstiest I’ve ever been. Relief was plentiful at camp: a flowing creek filled with beautifully clear water filtered by the roots of tall cottonwoods. I drank a lot. I had potatoes and salmon for dinner while enjoying the silence of that shaded creek bed. It was a stark contrast from the wind and tire buzz-filled highway descent an hour before. As the sun set, I unrolled my bivy into the divot of sand I had cleared. It was comfortable. It was soft. I fell asleep to the sound of burbling water and the breeze on my bag and the boughs above me.

The sun presented itself as I spun my way up a remote stretch of highway. Cars were kind, and the trucks were understanding. Nobody came scarily close. I climbed 4,000 feet over several hours to start the day. The higher I went, the rougher the surface became. Fresh tarmac became rough asphalt became gravel became washboard. I checked off what I thought was the difficult point of the route sometime around noon: the saddle between the Bears Ears Buttes. The land ahead was filled with windswept pines, snowbanks, and wheel-stopping mud. For some reason, I plunged right in. How bad could it get?

It got pretty bad. I thought I had endured the worst possible hike-a-bike on a previous trip to Montana. On that ride, my buddy and I had thwacked through brush and talus fields for 10 miles. The difference was that the temperature had been pleasant and the camaraderie was uplifting. Here in Utah, I had no friends and an excess of cold wind. Snowbanks replaced the talus. You don’t ever swim through talus. I have a vivid memory of making it to the first snowbank and thinking how fun a bit of snow would be compared to yesterday’s sunny-sandy suffering. Ten snowbanks in, and the novelty started to wear off. Twenty snowbanks in, and I was no longer having a good time. Thirty snowbanks in, and my socks were soaked with blood. Pulling my feet out of the snow and through the icy topcoat of the drift had left hundreds of tiny cuts on my shin. Even now, the speckle of scars is still quite clear on my shins.

Wheel-stopping mud made the snowless sections impossible to ride and nearly as difficult to push through. My wheels wouldn’t even turn unless I stopped every 50 feet and cleared them with a stick. A trail of mud and blood marked my passage through that time and space. Some of the drifts were short and (not) sweet, while some dragged on around corners and out of sight. One such corner had me waist-deep in snow with my bike held overhead. I envisioned a soldier fording a river, doing his best to keep his rifle dry. The only way he was getting out of that place was with a dry rifle. I had to keep my rifle dry.

After seven hours of almost no riding, every plunge into snow and every cleaning mud off the tires ended with me falling to the ground in exhaustion. I was low on calories and out of Snickers. I would sit for minutes at a time, no longer needing to catch my breath but unable to lift an arm to push myself back up. My body weighed more than it ever had. Walking felt like those first few moments of pedaling a heavy bike. On this trip, I recorded myself talking on my phone. I’m not quite sure why; I hadn’t done this on previous trips. Maybe it was to fight off the loneliness. Perhaps I thought I could trick myself into talking. I watch those videos from time to time, and even two years later, the emotions roll over me. The breaks in my voice stand out; I was close to tears but too tired to let them go. There I was, sitting in the mud, covered in blood, with nothing but trailside wisdom to discuss. It was a good distraction. It was procrastination.

The only thing that got me up and moving again was trying to run the calculation in my head of whether or not I’d make it to a lower elevation before sunset at the pace I was walking. After seven hours, I had made it only 15 miles and was absolutely destroyed. I was beyond bonked. Fear built after I concluded that I wasn’t going to make it down to warmer elevation before nightfall. I’d be spending the night up here at 9,000 feet. My lizard brain kicked in, and instead of looking for breaks in the snow, I was looking for enough snow or a fallen tree to get me out of the wind that had started picking up in the more exposed stretches. My pace quickened. I wanted as much time as possible to make my shiver bivy as comfortable as possible. Needless to say, when I came around a corner and saw a forest service outhouse perched next to a meadow, my heart nearly leapt out of my chest. Maybe I wasn’t going to be sleeping in the snow.

My life will forever be spent chasing the emotions that washed over me when the door of the outhouse swung open on well-greased—and most importantly—unlocked hinges. I was the richest man in the world. My room for the night overlooked a high alpine meadow. The sunset was lovely. The latrine didn’t even smell like shit, but nobody believes me when I tell this story. A quick inspection of the depths revealed no soul had enjoyed the throne in a while. It was clean as a whistle, probably getting a wash right before the season ended. I was perhaps the first guest in months.

I cooked my Idahoan potatoes and salmon… and could not eat them. After I had stopped moving, I became nauseous from the day’s effort. I made my bed in that windless space under a pine tree air freshener. You know, the one that might hang from the rearview mirror of your Grandma’s Buick? Yeah, that one. But that day, it graced a forest service latrine. Exhaustion quickly pulled me into the depths of my sleeping pad. I fell asleep soon after. I was shattered, but I was sheltered.

Around 3 a.m., I woke up to a growling stomach and intense hunger. My platter of potatoes and salmon, cold and ignored in the dark, felt like a banquet. I scarfed it down and snuggled back into my down cocoon, pleased with myself. I fell asleep with a smile. I remember that. I remember that well.

Morning brought stillness. The wind had calmed. No longer was I listening to the howl rushing over the outhouse chimney. I opened the door to a crisp and clear morning. If air came from a spring, this was that air. I made coffee. After looking at the map, I decided to alter my route. I no longer felt like riding the 40 miles into Canyonlands. I was already a day late to meet my friends. I had done my due diligence and already saved an alternate route (right on Beef Basin, not left) in RWGPS. I was young, still am, and feeling prepared isn’t a frequent feeling. As I write this, a paragraph from the fifth issue of The Bikepacking Journal rings in my ears:

“If planning is an effort to restrict an adventure to expected outcomes, I think there’s a case to be made for sometimes loosening up a bit and sensitizing ourselves to subtle external forces in the environment. If the intent is to appreciate the character of a place, we should also respect its recommendations, or at least update our plan with new information, gleaned as we ride. Although it’s no replacement for appropriate preparation, making room for a dash of serendipity is a guaranteed recipe for memorable travel experiences.” —Josh Meisner, “Slower”

I listened to the route’s recommendation. This counsel led to what might be the most enjoyable descent of my life. After finishing my coffee, I quickly packed my bike. I was hoping for free passage over frozen mud and snow from the cold of the morning. Regardless, I taped my socks to my leg warmers before setting off. My shins were raw and tenderized, and I was hoping to avoid more damage.

My early start paid off, I did no post-holing and enjoyed riding over snow banks many feet thick. I reveled in the sunshine, fully aware that I would be enjoying a 30-mile descent into Indian Creek in five short, firm miles. I took my time. Coming up on the intersection of Beef Basin Road marked the end of many things. It was the end of mud, but most importantly, the end of the hardest 20 miles of my life. It had been a lesson in digging deep, and I felt emotional at that little intersection of dirt. The next 30 miles went by incredibly smoothly; it was the most pleasant ride of my life. Clean, wide roads let me enjoy the surroundings. It was canyon country at its finest.

This day was pure Type 1 fun. It was in-the-moment joy. I spent my pauses at overlooks listening to raven calls. They’re my favorite birds, and I tend to only see them in these potent places. Their calls tell me that I’m not at home, and that makes them special. They’re comrades in adventure. I love them dearly. They also signaled that the end of my ride was near as they weren’t hanging out in the cold up high. At this time of year, they stuck to canyon bottoms where there’s water and warmth. That, too, was my goal.

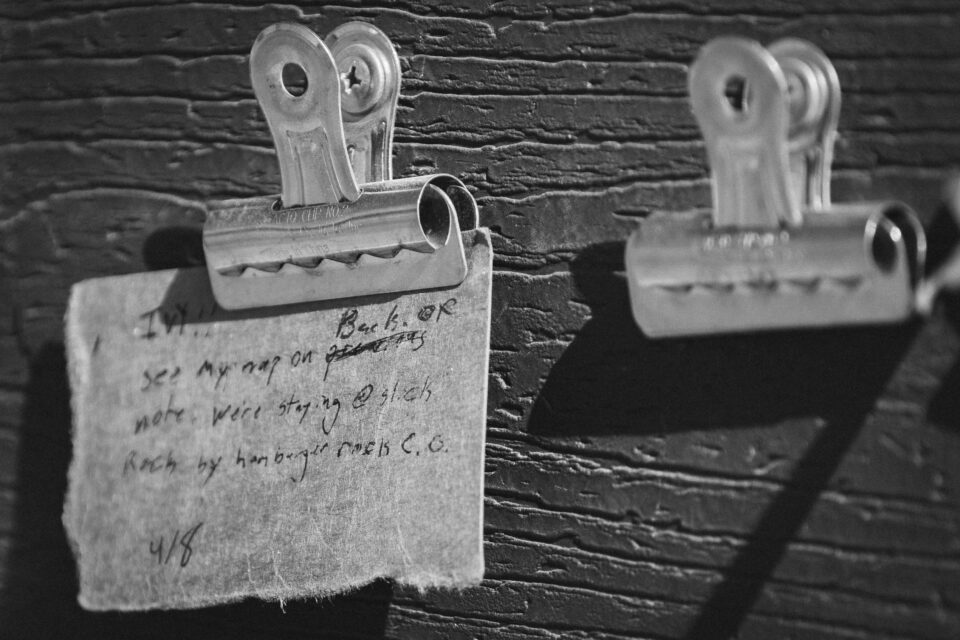

I made it to the message board at the end of Beef Basin Road. Indian Creek is home to my favorite form of communication. There, notes and hand-drawn maps replace the phone signals kept at bay by steep walls and isolation. A message scrawled on the back of a grocery receipt told me that Eli and Jess were climbing at Optimator Crag. I turned around and pedaled back up to the parking area, dropped my bike at the car, and hiked up to where they were climbing.

Jess tells me she will never forget the blood and mud-covered creature that came around the corner that day. I ended up napping back down at the car for much of the day. We decided not to throw my bike in the trunk and instead strapped it to the roof of a new friend’s truck to get to camp. Per usual in Utah, this trip was a first for many things. Haphazardly strapping my bike to the roof of a stranger’s car is one of those firsts.

When I think back on this trip, there’s one last thing that stands out: I listened to very little music and thought of even less. In the months leading up to it, my rides were filled with music. My commutes to work at Angry Catfish bike shop were filled with music. My river bottom rides after work were filled with music. I curated playlists simply to ride and listen to them. I did lots of processing and listening on my rides, but not this one. To this day, I’m not entirely sure why. I recall not thinking about many things, not about school or friends or the multitude of things my brain chaotically jumbles through at a violent velocity. I brought headphones and remember looking forward to podcasts and music, but on that ride, they didn’t seem appetizing. For some reason, tire buzz, the crunch of snow, and squelching mud proved the only soundtrack needed.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.