The Whaleback: Riding and Rafting from Wold to Humber

Share This

With his winter travel schedule mostly cleared by the pandemic, photographer Chris McClean headed out for a unique trip right from his front door, using a bike and packraft to rediscover an area in the North East of England that was a playground for him growing up. Read his story of finding joy and gratitude in his backyard here…

Words and photos by Chris McClean (@chrismcclean)

The Whaleback is a sandbank lying inside the Humber Estuary on the east coast of Northern England. As kids, we’d sail out to it and run over the soft sand to the waves on the other side, where we’d surf and gaze at the fort, a relic of the Second World War. On calm days, we’d set out swimming to it and use it as a diving board.

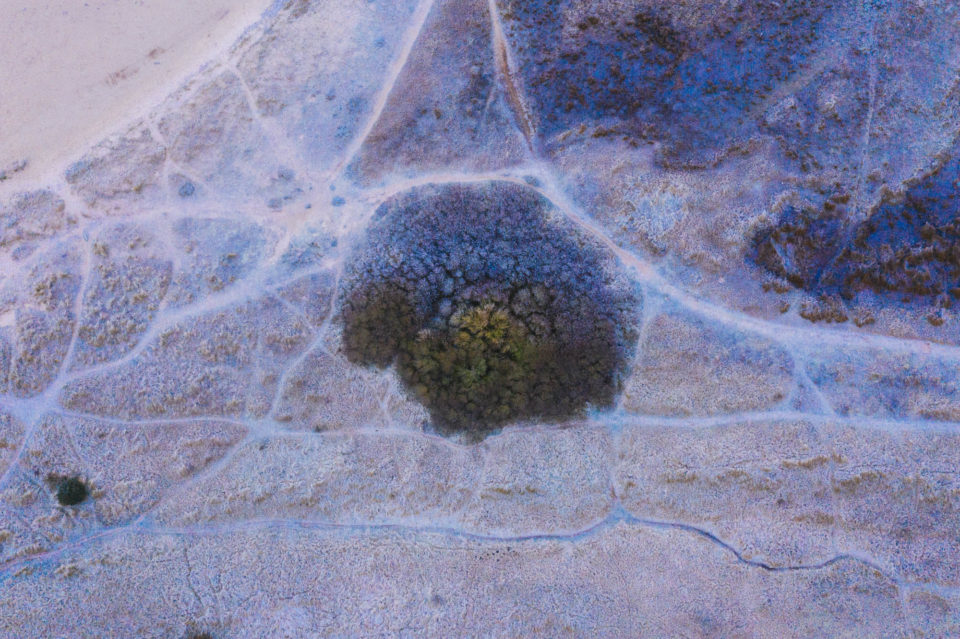

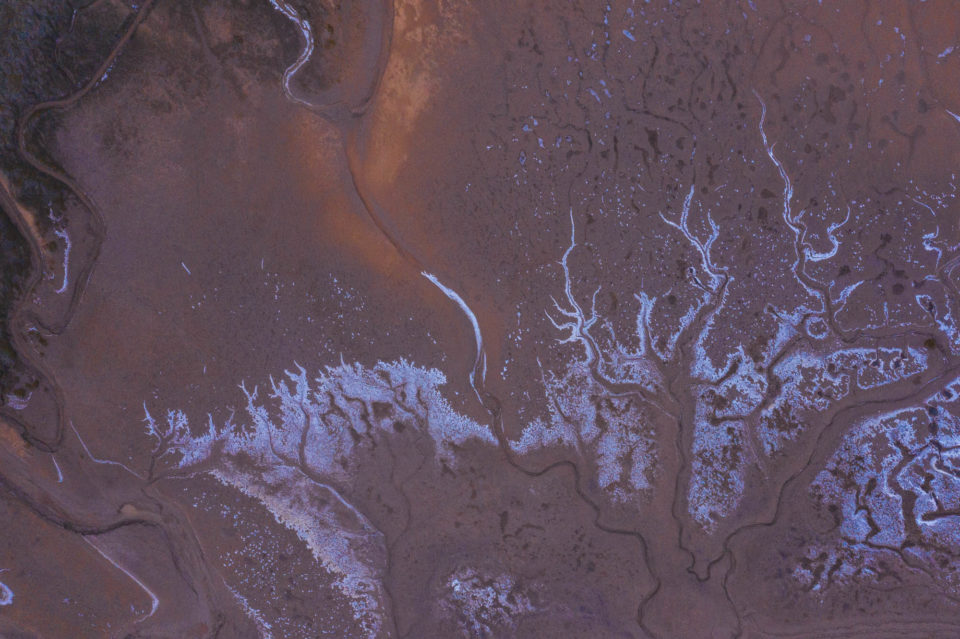

But inside the sandbank was our playground. We’d swim, sail, and canoe on the big tides when the mudflats were underwater. And then on the low tides, we’d ride when channels weaved their way through the marsh, draining into the Humber. We’d swim in the creek and roll in the mud until we got too cold or our parents called us home for tea. Those young teenage summers were the best. We knew the area and its dangers like the backs of our hands. Quicksand (and quick-mud), currents, shifting sands, and mudflats—we navigated them all without serious incident.

The Humber Estuary is the second largest coastal estuary in the UK and the largest coastal estuary on the east coast of Britain. Around 20% of the total land surface of England drains through it. Every tide carries over 1,500 tonnes of sediment through the estuary. The deposited sediments maintain its important habitats, which include mudflats, sandflats, and saltmarsh. A rich variety of species call it home and it’s recognised as one of the most important estuaries in Europe for overwintering birds. Hence, it’s earned many nature conservation designations under UK, European, and international law.

It’s hard to describe how close to my heart this area is. I was born into a house less than a hundred meters from the high tide line. My current home gets covered in salt when an east wind blows. And the sound from the migrating geese, boats, and fog horns wake us in the mornings. Yet it’s an area that I’ve never explored in detail since moving back. Trips away have always been to more exotic locations. The mission out to the sandbanks for surfing is a long paddle, and a dangerous one at that. And the local hills, although fun for cycling, haven’t felt like they warrant overnight camping trips. So, my favoured pastimes have always taken me away from my own backyard.

But the last year has changed all that. My lens has brought the local area into a sharper focus. I’ve spent more time on the sandbank, paddling up the creek and slip-sliding over the mudflats than during any period since my teenage years.

My Alpacka raft had been sitting in my garage waiting for a mission that lockdown had curtailed, so I felt compelled to get it out for some kind of adventure. My plan was simple: ride to the highest point of the Lincolnshire Wolds and back home via the Louth Navigation (or the River Lud before it was canalised). If I timed the tides right, I would join the canal with the tide just off high. And as the tide turned, I would be gently pulled along and out into the Humber Estuary beside the Whaleback before turning for dry land and beaching the pack raft just five minutes from my door.

I set off at dawn on my first-generation Fairlight Faran that has served me well on countless missions, riding through the suburbs en route to the Wolds. The village of Normanby le Wold is around 35 kilometres from my house and I wanted to take a few off-road detours on my way there. The air was fresh and a heavy frost coated everything as I pedalled along. It was a beautiful, crisp morning and I didn’t stop for long to take photos, especially since I had to keep moving to stay warm. When I did stop, my fingers became numb as I fiddled with my camera.

Wold Top is an imposing 168 meters above sea level and marked by a triangulation point hidden in a hedge. Even more imposing is the air traffic control radar that sits close by, looking like a massive golf ball atop a plinth. The sense of the wild is different out there, and the skies are big. It’s empty apart from small villages and smallholdings, and it’s so vast that it makes you feel small by comparison. I’ve been out there many times, but it was the first time I’ve taken the time to properly soak in the surroundings in such a way.

The sun had disappeared and the warmth that had me shedding a layer was gone as I started my way south. A few flakes of snow fluttered in the still air, and as I dropped into a valley around Tealby, the frost was thick on the trees and foliage. It was incredible. I stopped to shoot the crisp white foliage, taking some time to get it just right. Back on the bike and conscious of missing the tide, I made a bee-line east.

At Tetney, I left the road and cycled along the muddy riverbank. The frost was gone but the temperature couldn’t have been much above freezing. The sun never came back out and the day took on a murky, flat, grey tone. I picked my launching point and unpacked my Alpacka Caribou raft. I’d managed to pack it inside my Ortlieb front roll with the oars underneath on my front pizza rack. It didn’t take long to pump up, and soon I was taking wheels off the Faran and strapping them to the raft. The tide had started to ebb out and the muddy bank was starting to show. The tide drops two or three meters there and I knew getting down the steep, muddy banks would be a nightmare if the tide was any lower. I also had no idea how long it’d take me to paddle downstream to my landing point. I’d estimated it to be a seven-kilometre paddle with the tide in my favour, but the wind was picking up. When I turned into the open water of the estuary, I was sure to have a headwind. I had no idea how the raft would handle the chop.

The waterway I paddled on goes back centuries. The River Lud was turned into a canal in 1770 when the market town of Louth became prosperous and the town corporation wanted the opportunities that a link to the North Sea would provide for trade and expansion. It was straightened in places, and eight locks were added to overcome the difference in height, but all this infrastructure has since fallen into disrepair. The locks are now waterfalls and nature is gradually reclaiming the canal.

I paddled past the final sea sluice where the banks are high and I couldn’t see over them. It felt like I was blinkered. The sound was deadened and the calls of the bitterns and oystercatchers rose but I couldn’t work out what direction they were calling from. A merlin circled and bubbles rose from the muddy water. It was disorientating, and I was miles from anywhere or anyone. If anything went wrong there in the middle of the saltmarsh, I’d be a long way from help. I passed “Seal Bridge,” a channel created in the marsh to help lost seals get back to the sea. And then I turned the final corner and paddled down the last long straight into the Humber past the marker of the mouth. I paddled to the Whaleback and then briefly to land to stretch my legs.

From my vantage point, with the fort behind me, I couldn’t quite work out how high up the tide was on the far side. The thought of dragging the raft and bike over the mud scared me. It’s downright dangerous there, and I’ve had to call the coast guard out to help people trapped in the quicksand many times over the years. It was unnerving to think about what was beneath the water I’d be paddling over. I didn’t stay long and dwell on it, so I set off with the headwinds causing a concerning chop.

Thankfully, my raft coped admirably. It sits high on the water, so it didn’t slice through the waves, and every now and then one breached the boat and sprayed me. I had to point further west than I would have liked to keep my nose heading into the wind and over the small choppy waves. Waves to the side would be likely to capsize me, and the thought of swimming in the near-freezing water in my bibs was far from appealing. This part of the journey was a slog, and with the wind strengthening, I was getting cold. Scanning the coastline looking for the best spot to land, I remembered an old slipway that could give me an easy point of exit.

I landed and dragged the raft up onto the beach beside the slipway as the tide was a little too low to get up on the slipway itself. Plus, it has decayed just enough so there is now a big step up. This was the toughest part of the journey. My hands were numb as I removed the bike from the raft, put it back together, and deflated the raft to pack it up. I put all my layers on and worked as quickly as I could to get some heat back into my body. The feeling in my feet and hands had gone so I was rushing. I strapped everything to my bike in double time, not quite as well as I should have, but I only had a five-minute jaunt home.

Those five minutes of riding on my way home were filled with elation. I was cold but I was smiling, knowing I’d almost completed the task. I felt the same feeling that comes with the end of any adventure, even the bigger ones. In this case, it was a kind of lukewarm fuzzy glow.

Back home, as I relaxed in the bath with a cup of hot tea, I contemplated the ride and paddle. It felt like I’d seen my local area through a fresh set of eyes. From the highest point of the Wolds with views towards the Humber, all the way down to sea level in my boat. I’d travelled through the dense suburbs and out into the loneliest place in the vicinity. I’m thankful to have this available to me just a short step from my backdoor. I’m grateful to have such a wild and wonderful place to ride, paddle, cherish, and enjoy, and I can’t wait to get back out and see more of it with this new perspective on my next adventure, however long or short it may be.

More on Bikerafting?

Make sure to dig into these stories, routes, and guides...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.