Winter’s Gifts: Bikepacking 1,000 Miles on the Iditarod Trail

Share This

Huw Oliver traveled from Scotland to Alaska to ride the 1,000-mile Iditarod Trail last year, and he put together this reflection that links a series of memories from several weeks out on the ephemeral trail across the rugged Alaskan backcountry. Read his story of braving the elements and making unexpected connections here…

Words and photos by Huw Oliver

It’s sometime after 11 p.m., and although we’ve had some protection from the wind since leaving the open coastline, the wind-borne snow still needles me as it sneaks through the gaps around the edge of my hood and goggles. Ever since we left Elim, we’ve been following the trail across the sea ice of Golvin Bay, heading towards the lonely red light of a safety beacon set up on the far side some five miles away, which helps travellers find their way across the ice when ground blizzards obscure the trail and its markers.

I hate to admit it, but I’m flagging. Nearly three weeks of long days on the trail has left me drained and sorely wanting a rest day. A storm is on its way, though, threatening to blow in the trail with drifted snow and reduce our progress to a tortuous trudge. So, with the pace dictated by the weather, we ride on into the final night of the journey, hoping to make White Mountain before we finally set up the tents.

Two extra light sources join the unblinking red beacon. The first is a smudgy aurora that’s been drifting in and out of focus in the inky sky above us all evening. I saw the best display of my life three weeks before, during the first night on a frigid Yentna River. Now it’s back, bookending the journey with a sight I find impossible to tire of. The second lights are a series of floating white pinpricks, picking their way across the ice towards us. After a while, the sound of snowmobile engines is loud enough to be heard over the crunch of tyres and the huff of frozen breath.

There is the smell of petrol fumes as the first machine pulls up beside us, and we see that an entire family is packed onto the seat and into the sled being pulled behind it. They ask us where we’re headed, how the trail is, and how we’re doing. An everyday conversation between travellers, with a surreal tint to it out on the ice a little before midnight. Another sled passes, then another, all packed with families heading back to Golovin.

We learn that the big inter-school basketball match occurred that evening in White Mountain. School basketball is huge in rural Alaska, and we’ve frequently seen their various mascots displayed proudly, from the Wildcats in Kaltag to the nanuq, or polar bear, in Nome. I think with an amazed smile about how these families have travelled across the frozen sea in open sleds behind snow machines to watch the big game and are coming home through the drifting snow to Golovin. I don’t remember who won. After a friendly five minutes on the ice, we were all getting cold, so we went our way, and they went theirs to disappear in the darkness quickly.

If I had to sum up western Alaska in one encounter, I suppose that might be it. Alaska is synonymous with its vast landscapes. At around two-and-a-half times the size of Texas, that reputation is well-earned. Coming from a country where I can comfortably ride coast-to-coast in a day, it was discombobulating. It took two whole days just to cross the 70 miles of frozen swamps and stunted, burnt trees between Rohn and Nikolai, a relative nothingness in the context of the entire trail. Picture the Iditarod Trail like a snowflake, though—one of those big, fluffy ones you get when the temperature is near freezing—and it suddenly becomes fractal, every tiny detail hiding others that were hidden within it, and so on. As I try to distill the whole journey into a measly few thousand words, I get distracted as pieces fragment into different sights, sounds, or feelings until I can’t remember what I was trying to talk about in the first place. There’s too much there, hiding in the folds.

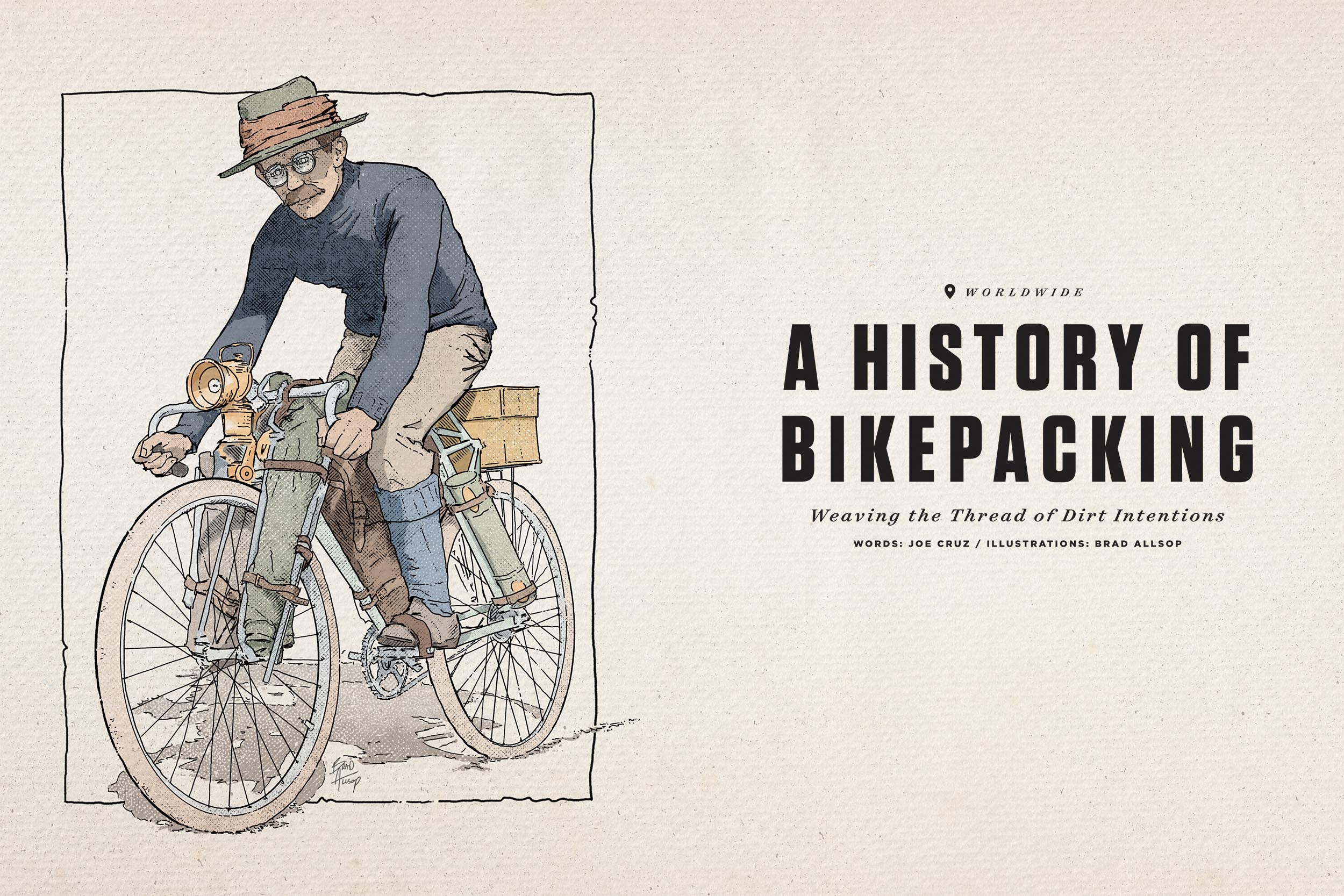

The Iditarod Trail, all 1,000+ miles of it, is, of course, the historic overland route that connected south-central Alaska with the mining camps and gold boomtowns of the interior and beyond the Yukon to the coastal communities of the Norton Sound and Seward Peninsula. Its Western-centric history might be tied to the gold rush of the early 20th century. Iditarod, its namesake, is a mining ghost town that once housed 10,000, but the route it traces has its roots in the trading corridors that have linked interior and coastal native communities for far, far longer.

Air travel might have brought about the decline of the Iditarod Trail as a supply route, but since 1973, the Iditarod Sled Dog Race has revived interest in what is surely one of the most scenic winter journeys anywhere in the world. The trail itself exists only for a few fleeting weeks in late winter when it is broken in for the dog race. When the snow melts, much becomes flowing rivers, open sea, or mushy swamps with the odd trail marker stuck forlornly on a tree. Briefly, though, there is an unbroken trail stretching from Knik Lake, up the great rivers that drain the Alaska Range, and over the Range itself into the interior, across the endless swamps to the Yukon, and through to the Bering Coast, and finally to Nome. It’s a tantalising, sinuous connecting thread that had whispered into my ear since the first time I read about it.

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, as the saying goes. The Iditarod Trail is no exception—and it happens to cover the same distance—but after that first step, or pedal stroke, come countless others. Such a long winter journey will always be an intense experience, demanding a significant downpayment of preparation and exertion to see it through. But just like our snowflake, it’s the sum of a thousand tiny but essential daily actions, all of which bring their own reward.

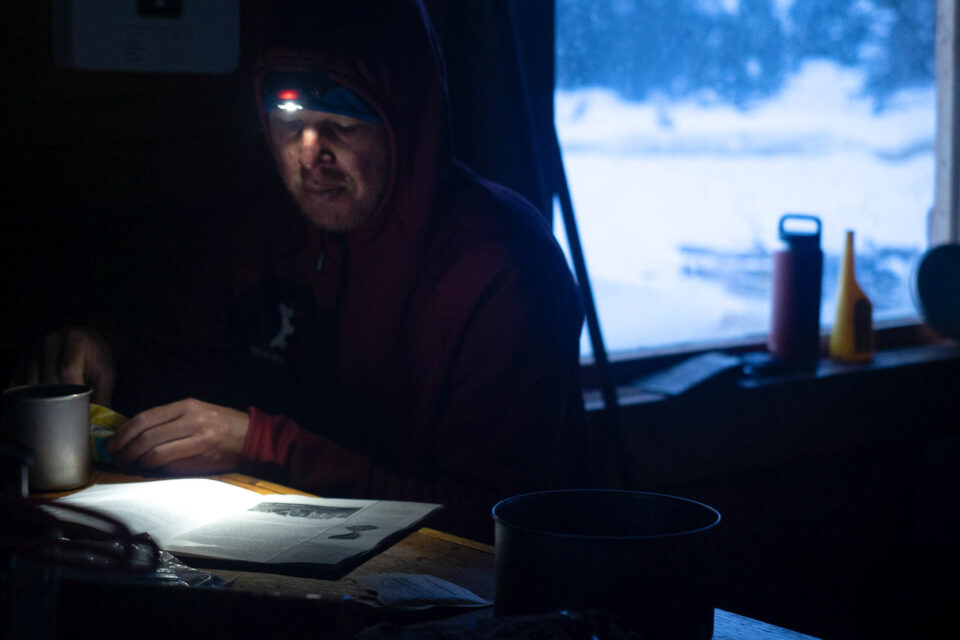

Each day begins with the sting of cold on my nose since it sticks up like a periscope from my sleeping bag and is the only piece of skin left uncovered, except on the coldest nights when a nose-cosy is needed. The next sensation is sound, or hopefully the lack of it. Whether or not I can hear the wind tells me what sort of day is waiting on the other side of my tent’s cosy cocoon. Priority number one is staying warm, but at some point, we have to stir and emerge from hermetically sealed sleeping bags because the need to pee eventually bumps warmth from the top spot. I wait until Kurt and Nick are definitely also getting up before doing this. Our aim, before reality pegs it back a little, is to cover around 50 miles each day. That means a long stint on the trail, which means getting up before the sun can rise to bring light and warmth.

Priority number two, once enough layers of down clothing have been put on, is food and water to fuel those 50 miles. We generally carry four or five days’ worth of food at a time, so everything has to be dry and calorie-dense: plenty of porridge oats, dried mashed potato, or perhaps one of those fancy freeze-dried meals. Food becomes an all-consuming obsession when your body burns recklessly through calories to stay warm. I go to bed thinking about food and wake up looking forward to it. All in all, it takes around two hours from getting up to getting rolling on the trail: priming stoves, melting enough snow to provide a day’s drinking water, eating as much porridge as we can stomach, and getting our gear packed while avoiding hot aches in our fingers. All of it is slowed by the frustrating faff of doing fiddly tasks in big mitts.

No day on the trail is the same as the day before: changing scenery, snow conditions, and weather can make the going slow or swift, dull or dazzling. The exception is the Yukon River. I’ve ridden through big landscapes before, but at the best part of a mile wide, I didn’t ever quite get my head around how a river can be so big, even after riding up it for 130 miles. We were lucky with the weather on the river, too: as the lowest point in the topography of the vast interior, it becomes a sink for chilled air and a funnel for winds, all of which can make it a very unpleasant place to be. Aside from a few miles of pushing near Eagle Island and some sinky snow, we just had to deal with the drudgery of endless flat miles after the ethereal, hilly miles of the Kuskokwim and Innoko drainages.

An ITI racer just behind us was stuck walking his bike for days after a windstorm blew in and obliterated the trail on the Yukon. The river is a good place to meet fellow travellers, though. On a particularly cold night, we’re passed by Jason Mackey, a musher who is instantly recognisable in his red suit, and he stops to chat and compare experiences so far as the light bleeds out of the sky. It’s comforting to know that other folks are out there on the river, even if they’re travelling by dog-power rather than human. We often pass the straw piles that give away a camp spot for the dog teams, and I wonder whether the mushers are lonely or if the dogs are all the company they need.

The race takes over the trail in a way that electrifies the places it touches, with news and rumours passing between lonely checkpoints and villages like the crackle of static. We have already been riding for several days when the first dog team catches us deep in the interior past McGrath. It’s a dull, overcast morning, somewhere around -15°C, and we’re traversing the northern slope of the Beaver Mountains across a series of long rolling hills through bristly black spruce trees that remind me of upturned toilet brushes.

Fat bikes are surprisingly noisy as their tyres spread across the snow, but whenever we stop, the silence of the interior feels deafening. During a snack break, the shushing of runners and whispered pants from many mouths slides gently into earshot through the spruce, followed by the first team to make it through from Knik. After a brief greeting, the musher and his team glide out of sight over the next roller, so quickly and quietly that we’re left in no doubt that the dogs will be leaving us in the dust all the way to Nome.

The buzz of the race is everywhere. In McGrath, the army of volunteers known as the Iditarod Airforce is in constant motion, organising bush flights in and out of remote checkpoints, loading and unloading bales of straw and crates of food for the dogs to fly them out whenever the brief weather windows allow. In Anvik, a village on the Yukon, the schoolkids have hand-drawn posters to gee on their favourite mushers. Every village feels alive and on tenterhooks for news. In fact, the mushers and their teams are the quietest part of the whole thing, passing us like ghost ships in the night while we lie in our sleeping bags. For around a week while the teams move through, I get used to the comforting whisper of sled runners and jingling harnesses when I wake briefly to roll over in the night. In the ghost town of Iditarod itself (an important checkpoint for the dog teams) we’re just a sideshow, hovering around the edge of the action like ravens after scraps.

With their attention given over entirely to caring for their dogs and ticking miles, we’re rarely able to chat with the mushers and satisfy my ever-increasing curiosity. At checkpoints, as soon as the vet checks are completed and the dogs are bedded down, the mushers are quickly unconscious as they try to get some precious sleep, sometimes lying on the straw beside their teams. Our luck changes when, on a mild and sunny day somewhere just east of Shageluk, we pile into the Big Yetna safety cabin to make some lunch at the same time that Mike Williams Jr. decides to stop and feed his team theirs. After an initial awkward silence, we get to talking, asking after his team and how his race is going. He lives in Akiak, a village down the Kuskokwim River, and he tells us proudly how the food he’s brought is from his home, prepared by his family. He insists we take some, saying he has more than he needs.

First, there is dried king salmon, a whole bag of the pungent, dark orange fish caught from the river. Next is ice cream made from crowberries, blueberries, salmonberries, and lingonberries, frozen and mixed with caribou fat. The berries are tart, crisp explosions on my tongue after weeks without much in the fruits and veggies department. Mike saves the best till last, bringing out a small bag of muktuk, or whale blubber and skin. He says his cousins hunted it on the coast, and the small, black-topped white cubes are about as dense a calorie hit as you could imagine. It’s chewy but tastes fresh and satisfying in a way that is outside of my own experience. My body tells me that this is good, exactly what it wants right now, even as my head tells me I’m stupid for having expected it to taste fishy. It’s one of innumerable small reminders that while I feel immersed in the trail, in so many ways, I’m completely ignorant of what it means to be so deeply attached to the land I’m treading on.

Other trailside meetings remind me that rural Alaskan communities are surprisingly diverse. One morning, a day after we left the Yukon behind, we’re traversing the low-lying corridor of the Kaltag portage, which will deliver us to the coast at Unalakleet. I’m perhaps 10 minutes ahead of Nick and Kurt, enjoying the tailwind buffeting us westwards at the same rate as the snow crystals that hiss past at ground level. On a rise, I meet two snowmobiles, ridden by women from Unalakleet, out on an ice-fishing trip for char from a nearby spot. We exchange names, and when I ask about their unusual surnames, it turns out that one of their husbands is Danish, the other German. Both had visited Unalakleet in the past and decided to stay. Looking around in the brittle sunshine, I can see why. To add another unexpectedly European element to the day, when we do eventually reach Unalakleet, I eat the biggest, tastiest, and most expensive pizza of my life at the Peace on Earth pizza joint in town.

The day’s riding is broken up by short breaks and maybe a longer stop to boil water at lunch if we’re feeling decadent or if there’s a cabin. The riding is beautiful and engaging, but every evening, my mind drifts towards dreams of being stationary and well-fed. These daydreams always involve the cosy surroundings of a sleeping bag, and a mug of tea looms larger and larger in my mind. After several long and monotonous days on the Yukon, the village of Kaltag feels like Christmas come early.

As is common, the school there also functions as a community centre and offers a place to sleep for the night for travellers. After finding the principal, paying him a fee, and eating monstrous amounts of food in anticipation of hitting the village shop in the morning, we bed down in the sweltering school gym hall. I’ve begun to notice that I sleep poorly indoors, preferring the quiet of the trail and the snugness of my sleeping bag cinched in tight. Several ITI 1000 racers are also staying at the school, leaving early the next morning. We’re in no great hurry, so we agree to hang out and chat to some of the kids when they arrive for school. My curiosity for new friends on the trail is nothing compared to that of the kids at school in Koyuk. Eleven-year-olds are the same no matter where you are, and I recognise the same cheeky smiles and excitable energy that I see in Scottish kids at work back home.

I can tell, when Nick introduces himself, that Anchorage is a comprehensible but faraway place in the kids’ minds. When it’s my turn, I point out Scotland on a map, but I’m not sure they believe me at all. Fair enough, though—when I was 11, I could only just understand how far away France was, and we’re a lot further than that from Anchorage. The kids get straight to the point and demand to know whether we have Fritos in Scotland. There’s dismay when I say no and real concern when I say we don’t have Chex Mix either. At last, we find some common ground, and there’s relief that we do at least have Pringles in our Scottish culinary desert.

From pogies to Pringles, this might be a disjointed sequence of frozen moments, meetings, and memories, but as with any long journey, the only way to grasp the whole is through the smaller details. Winter demands extra attention to the minutiae since so little is given freely. What strikes me most, though, is the fact that the Iditarod Trail is only passable for a few weeks each year, when snowmobiles, dogs, bikes, skis, and feet create and maintain that ephemeral sliver of snow and ice that stretches from the Knik Arm all the way to the Bering Sea.

Like a snowflake, its beauty is inextricably tied to its impermanence. As I write, so many of the places I’m remembering have transformed into swamps, flowing rivers, and open sea. Jumbled memories they might be, but already they’ve proved to be longer lasting than the trail on which they were made.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.