Life on Mars

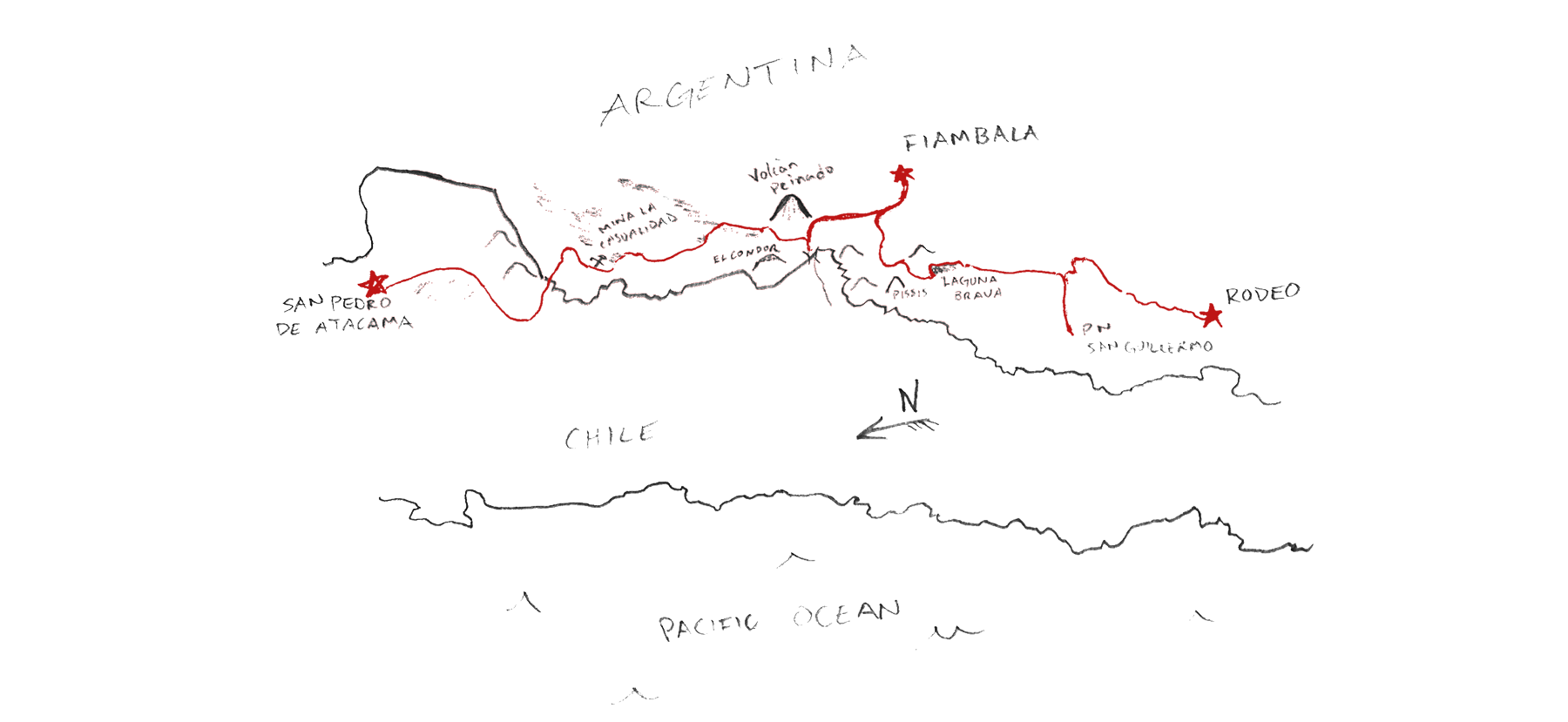

Skyler, Scott, and Rick set out to ride a 1300 kilometer route in the sublimely harsh Puna de Atacama desert along the Chile-Argentina border. Here’s Skyler’s tale of mental starvation, dizzying winds, mind-boggling scenery, and a harrowing river crossing.

I correctly identified Volcán Socompa on the horizon three days before we rounded its base and crossed the border. The going was easy at first, though it felt very hard at the time. Along a stretch of rough road, a beat-up Toyota pickup—the first vehicle we’d seen in a day—caught us while we rested at the top of a rise. Leaning out, a man asked where we were headed on this empty road.

“We’re going to cross into Argentina.”

Looking us up and down, he laughed incredulously through his sparsely toothed grin and made a series of exclamations that were beyond my Spanish comprehension. But the gist of his outburst was familiar:

“Well, god damn!”

The Border

Even though it’s remote and rarely used, this pass is relatively well-known to cyclists and is gaining popularity as the confusion about it diffuses. On the Argentine side, we were casually stamped in by a man in sweatpants and white Crocs. He allowed us to sleep out of the wind in an empty building that reeked from a barrel of used motor oil.

It wasn’t until a day later that we turned off the known route, now riding perpendicular to the gales that had pushed us up to 4,300 meters above sea level on that lumpy, narrow-gauge railway. From there on, the wind was a nuisance at best. At its worst, it was a heavy pack, a swarm of wasps inside our heads, driving us mad, a draining sickness. The first nights of our journey were calmer, with the gales building by noon and lasting until dark. But even this pattern gave up as we moved higher, passing between salt-bottomed basins and lifeless passes. Then the noise rarely relented. In gusts, it carried gravel to eye height. In lulls, it howled on in our ears, a deafening white noise. It wouldn’t let us forget that consciousness exists on the brink of insanity.

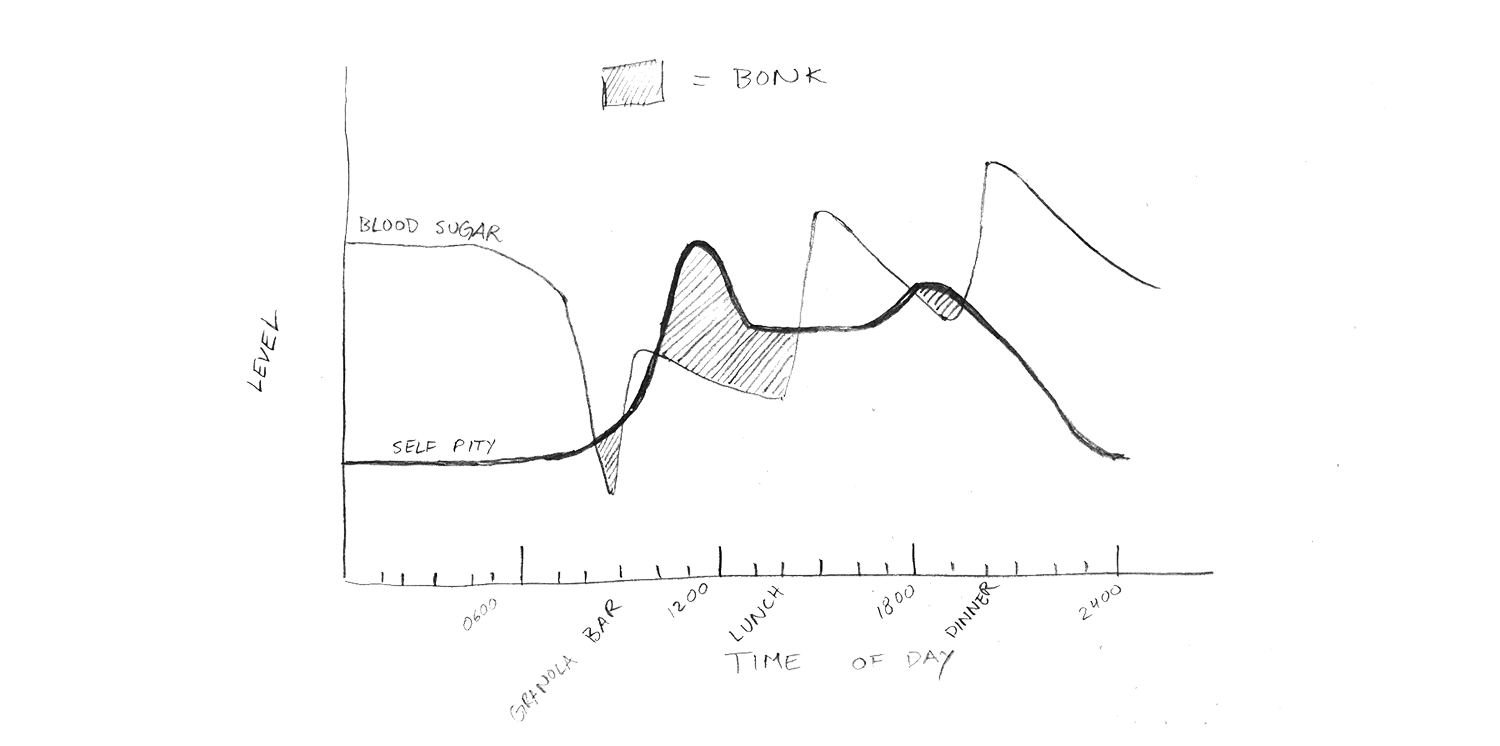

Ritual Morning Bonking

We got up with the sun each morning. I somehow failed to plan breakfasts, so I’d sip on a mug of coffee—instant Nescafé with powdered milk, of course—and pack my things. We were rolling before nine, and I was ravenous by half past. Most mornings, I managed another half hour or 100 meters up the first climb before stopping to smear a spoonful of peanut butter on one of Chile’s reliably disappointing budget granola bars.

Excursions deep into deserts and other austere places are said to inspire philosophical contemplation and divine epiphanies. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the world’s largest religions all spawned out of desert civilizations. But not this time. Not for me. Even my crippling existential terror was unusually quiet behind the din of the Puna’s eternal wind and my own self-pity.

Nope. I only thought about food. Specifically: how I could ration my food more sensibly, what I would eat next, all the things I really wish I’d bought a week earlier when there were stores, and how many cookies I could allow myself that day.

I’d been woefully casual and disorganized in the supermarkets of Calama, the modern mining city we’d flown into to begin our journey. Only through this constant food anxiety was I able to stretch my already lean 10-day supply to two weeks. The weight of the hunger slowed me down more than the weight of the food might have.

I don’t know what my companions Scott and Rick thought about all day. I doubt it was food, though. Scott seems to run all day on last night’s dinner. Rick is too cool to worry about such primal needs. He operates at some higher, Nirvanic level (and also lost more than six kilograms on this trip).

Thirst

When I wasn’t worrying about food, I thought about water, incessantly peering down at the scratched screen of my GPS to estimate how far we were from the next suspected source. Water scarcity was the real danger of our chosen route, which overlapped bits of Harriet and Neil Pike’s impressive and unparalleled ride through the region when they climbed nine of the Western Hemisphere’s 25 highest peaks on a single pedal-powered journey. But our routes were sufficiently different that, once in Argentina, only one of their water sources was of any use to us. Beyond that, we depended on rare freshwater springs (spotted from Google Earth by their greenery), snow found up high, and carrying a lot of water.

Leaving one of these oases, we were loaded up not with the spring water we’d expected but with bottled water from a mineral exploration camp we encountered beside it. This spring, which they called Vega La Brea, flowed warm and stinky, and we heeded the miners’ advice to avoid it. With the politeness demanded of the encounter, we accepted less water than we wanted and departed with only 10 liters each. We hoped to arrive at the paved highway at Paso San Francisco, some 130 kilometers away, the next day. From there, we’d leave our high desert route and hitchhike down to Fiambalá to rest and resupply.

Two nights later, we found ourselves halfway up a climb past the perfect cone of Volcán Peinado, still a long way from any pavement. We wandered between dunes and old lava flows, looking for a sheltered place to set up camp, eventually settling for the bottom of a sand-filled trough where the wind was imperceptibly lighter. In other words: still a full gale. In the 45 minutes it took to pitch our tents, we lost a few stakes that were catapulted by a flying tent. One gust threw Scott’s tent into his bike, tearing a hole in its side.

Finally cocooned inside my little tent, I looked over at my remaining water: one half of a bike bottle that I desperately wanted to drink. Through an itchy throat, I called into the wind, “I hope we don’t die.”

After a long pause, Scott replied from his tent, “I’m going to kill you if we do.”

Back on the bikes after a long and waterless morning, we finally found snow. Wrecked from dehydration, we made another windy camp at 4,950 meters, having only traveled 25 kilometers in a full day. The next day, our fourth out of Vega La Brea, we reached the paved road at Paso San Francisco, already two days behind schedule. We didn’t find any cars, however. The border crossing to Chile was still closed for winter, and our hopes of hitching a lift to Fiambalá, around 200 kilometers away, were dashed.

Easy Living

“So tough,” he nodded with his uniquely Californian intonation.

On one corner of Fiambalá’s town square sits the tourist information office and municipal building. On the next corner is the region’s police station. On a third corner of the square, you’ll find the unmarked office of Jonson Reynoso. You’ll know he’s in when there’s a battered Toyota Hilux parked nearby.

Jonson has several obscure official titles in addition to running his own guiding outfit, but he’s more or less the mayor of the Argentine Puna. His wealth of knowledge of the region is sought by mountaineers, the planners of the Dakar Rally, the government, mining companies, and, on occasion, cyclists. He’s the only person we spoke to who knew all the place names from the start of our trip, 700 kilometers north of Fiambalá, and all the names until its end, continuing south over the mountains to places that were several days away by 4×4 truck.

His office is stacked with mountaineering supplies and binders of documents. The walls are adorned with summit photos, gifts from the world over, and signed foreign flags. Amid the stacks, Jonson, dressed in unlaced work boots and an equally unlaced lumbar belt, sat down to give me a flyover on Google Earth. He had the rare generosity to patiently and politely correct my Spanish. Rarest of all, unlike what I’ve typically found to be the case in my travels, he didn’t conflate that which is difficult with that which is impossible. He didn’t try to talk us out of anything.

“Take this pass, east of Monte Pissis,” he said. “I walked it in 1986, and it’s less steep than what you had in mind.” Pointing at the screen, he continued, “The Pikes went here. It’s much higher, about 5,650 meters. Take the lower pass. It will be very hard, but you will do it.”

When we rode into Fiambalá, I was ready to quit the trip, hop on a bus, and get away from the Puna region. We weren’t prepared for a repeat of those first 14 days. The combination of tough riding, heavily laden bikes, high altitude, hunger, thirst, and constant wind added up to something demanding more mettle than I possess. But, after a bit of rest down in warm, thick air, we felt ready to head back into the mountains. This time, we were prepared for shorter days with food to spare. We left Fiambalá in Jonson’s pickup and were dropped off 3,000 meters above town at 4,600 meters, cutting out a few days of climbing and 100 kilometers of our intended route.

Los Seismiles

The corridor that extends from Paso San Francisco southward to the next road at Paso Pircas Negras is home to a concentration of high peaks, Los Seismiles. On top lies Ojos del Salado. At 6,892 meters, it’s the world’s highest volcano and the second-highest peak outside the Himalayas. Pissis, Bonete Chico, Tres Cruces, Cazadero, and Incahuasi are all above 6,600 meters.

I first visited this area in 2011 when I traveled around South America with a bag of mountaineering equipment. I hitchhiked to climb Ojos del Salado alone from the less-traveled Argentinian side. Arriving at the trailhead, I stared across the 80-kilometer void of wind-battered desert that lay between me and the peak. My pack was loaded with nine days of food, though I suspected a trip to the summit and back might take me 10. The next morning, I hitchhiked back to town, wondering if I lacked the courage or simply the desire to keep suffering. I never stopped thinking, “If I only had a mountain bike, this might be fun.”

Over the next six years, I periodically returned to gazing at Los Seismiles on Google Earth. In time, I mapped out many scraps of what looked like rideable 4×4 track. Over a din of sewing machines and many days spent together making bike bags in Scott’s shop in Calgary, I heard about his previous fat bike exploits in the Australian desert. These desert fat-biking stories gave the requisite spark of curiosity and belief to transform that cluster of cartographic tracings into a solid vision: a month-long route across the highest, driest region in the Western Hemisphere. Rick, it seems, had been down in his own shop in California, stewing with the same curiosity ever since he built Scott a long-tail fat bike fit for crossing Australia.

The next section, from Pissis’ base camp southward, was the longest stretch that followed no road or track at all. We simply chose the lowest pass, first to 5,250 meters, then along the edge of the glacier-filled crater Corona del Inca to a height of 5,530 meters. Of course, we mostly pushed our bikes up to that height while pedaling over flatter alluvial fields.

A general rule of high-altitude mountaineering is to climb high and sleep low, but we found ourselves setting up camp a few meters below the highest point of our trip at day’s end, hammering tent stakes into rock-hard permafrost while the wind wailed as usual. Or perhaps we were on a sand-topped glacier.

I got up to water the wind at some point after dark. It probably wasn’t late, as the sun sets quickly at lower latitudes. There was no moon, but I could see clearly under the unfiltered light of the stars. I looked for the Southern Cross in vain. The stars were too bright, in fact, to make out constellations. Innumerable dots of light filled the sky in a near-solid mass, and only our own galaxy painted a distinguishable shape across the sky in a great glowing streak. Perhaps I would have spotted our neighbor Andromeda had I dallied in the bitterly cold wind a little longer. But, after casting a quick glance at Rick’s flapping tent, pitched to half its usual height, I hurried back into my sleeping bag. We were so alone. We are so alone, chained to a star with a finite life, trapped by uncrossable expanses in a universe destined to go dark. Rick must have been freezing in his three-season sleeping bag on a thin foam pad.

Falling off the Map

More than two vertical kilometers below that frigid night, we reached the Rio Blanco, where we planned to enter Parque Nacional San Guillermo and continue south. Unexpectedly, we found a park gate. In a typically perplexing display of Argentinian policy, we were informed that we needed official authorization to enter the park, and the authorities at the gate lacked the authority to authorize our entry. They could only do so at the southern end of the park. After a half-hour stand-off, I finally accepted the futility of reasoning with a crew who were more interested in bureaucratizing the desert than the fact that they were leaving cyclists in a bit of a pickle. Instead, we leveraged our finite food supply to ask for a ride back up the massive climb we’d bombed down that morning.

I’ve long argued that the speed of a bicycle is a perfect pace for travel: it’s a human pace, yet not so slow that you can’t still cover some ground and see many places. But, while ripping up that washboard climb with our bikes clattering in the back of a pickup, it occurred to me that the Puna was an exception to this rule. The Puna is far beyond a human scale, and I suspect its greatest treasures and most otherworldly landscapes remain out of reach to those traveling without the aid of a motor. Even relatively short detours cost too much on a bike.

We were dropped at a faint junction back at the top of our morning’s descent. To our left, a wide gravel road would take us quickly to the end of our trip, a day’s descent until we reached a paved highway in a populated valley. To our right was a faint machine track that didn’t appear on any map. It looked as though a bulldozer had cut a road there once, in a single pass, many years ago, and it hadn’t been touched since. The park rangers had told us they knew where it came out—right back on track to our destination, Rodeo—but none of them knew anyone who’d ever traveled it.

The River

The dozer track was in worse shape than we’d expected. After hours of descent peppered with constant washouts, runnels, and thorn shrubs, we arrived at the river. Despite the fear of riding down an unmapped road, I felt relief at the sight of vegetation and the sound of rushing water. It was warm, the air was rich below 3,000 meters, the wind came in short-lived gusts, and I was suddenly reminded that bike touring could be fun. I had enough energy to enjoy myself. Our trail remained faintly visible even as we oscillated between ankle-deep marshes and exuberant off-trail mountain biking in the bottom of this monumental canyon.

Though I’ve forded many rivers on bike trips, I’d never considered how one might cross a river that’s too deep to wade. After two days of following the river, we’d already waded across it several times, and since hitting a graded, named road, we assumed that we had this trip in the bag.

Not so.

The road entered the river on a paved ford that formed a head-high weir on its downriver side. This far downstream, a confluence of valleys had more than doubled the size of the river. Though less than knee-deep until midstream, the water was moving fast. Another footstep would put me into deeper and faster water, and a slip would have sent me over the weir into a churning froth of river and rock. Scott and Rick hiked up and down the river, searching for a place to cross. I waited with the bikes, hoping a truck would come. One of Argentina’s ubiquitous four-cylinder pickups wouldn’t suffice, though. It would have to be a dump truck to avoid being washed off the weir.

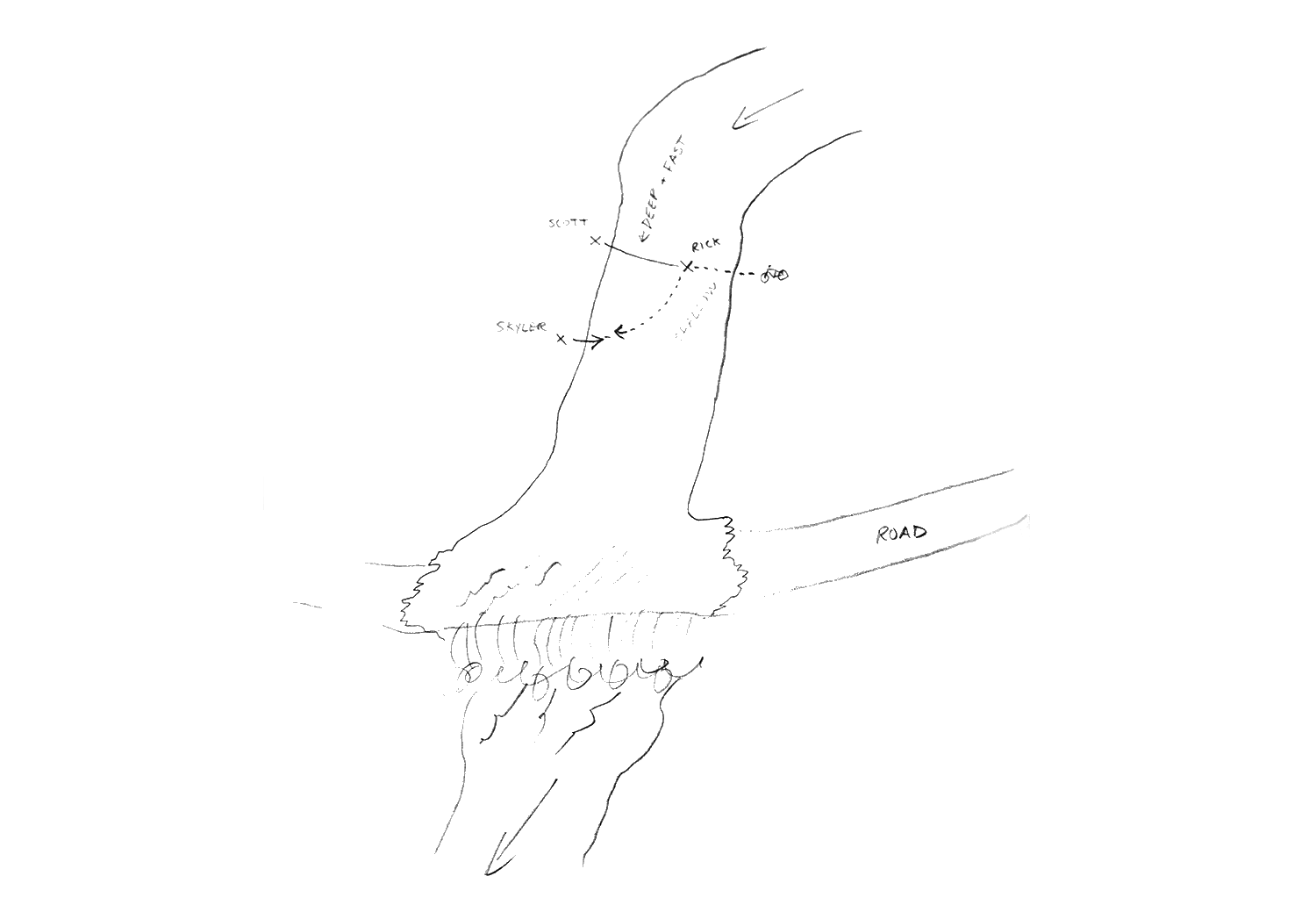

An hour later, Rick and Scott were back, having found nothing. But there remained an option worth pursuing if we only had enough rope: swimming. I traced out the play in the sand. Three players: a pitcher, a catcher, a human anchor, and a bike on a string.

“Swim for it, Rick!” I yelled over the current as his tent and sleeping pad sped down the river in a neat roll.

Rick hesitated, grabbing his hair in his fists. “Ahhhhhh, shit! It’s gone!”

But I was already running. It’s one thing to lose a tent, but it’s another to lose the one and only tent ever made by Scott, a project I’d been told would never be repeated. Slowed by the hole below the weir, I caught up after a short sprint and rescued the roll. Eventually, all the luggage made it safely across.

Scott stretched his arm over the current, leaving Rick just enough slack to tie one end of our rope around one of the bike’s headtubes. When Rick pushed the bike into the current, it would pendulum downstream, with Scott as its axis, moving toward the far riverbank. Each time, as the bike reached the apex of the arc, the front wheel flopped into the current, and Scott started cussing as the force on the bike multiplied. Meanwhile, I jumped into the stream, up to my navel, grabbing at the bike to help it to shore. Rick followed the third bike and emerged from the current grinning, reaching for a hug. Home free.

We reached a small village at 10 a.m. on our last day of pedaling.

“Is it okay to drink beer in the plaza?” Rick asked the woman behind the counter of a dimly lit, low-roofed store.

“Yes, but maybe only one. The police don’t like it when people get drunk in the plaza.”

Laughing, we filled our mugs with cold, pale lager and sat in the shade of big eucalyptus trees. We ate ham sandwiches for lunch.

Skyler Des Roches is a full-time troublemaker at Porcelain Rocket, and occasional contributor here at Bikepacking.com. For this trip, he assembled a Fatback Rhino FLT with support from Fatback Bikes. He was stoked to also be decked out in Canadian-made Westcomb Outerwear clothing, and Only What’s Necessary riding shoes. He lives in Calgary, Alberta.

Scott Felter is the owner and supreme leader of Porcelain Rocket. He’s into cats, home renovations, mountain biking, and big fatbike expeditions. His previous cycling trips of note include a self-supported completion of the Canning Stock route, and trips in Tasmania and Newfoundland. He lives in Calgary.

Rick Hunter is the mind and maker behind Hunter Cycles. He started making custom bicycle frames 25 years ago. He obviously built the frame and racks he used in Argentina. This was the longest “vacation” he’s ever been on. He lives in Santa Cruz, California.