Red Feather Ramble: Face to Face with the World

New bikepacker Pablo Selman recently joined a few friends for a multi-day ride on the beautiful Red Feather Ramble route in Colorado. In this reflective piece, published in both English and Spanish, he delves into themes of movement, camaraderie, and history and shares an evocative gallery of film photos shot on his 1950s camera. Read it below…

PUBLISHED Nov 18, 2025

Esta historia también está disponible en español. Léala aquí.

This journey began with a text from my friend Jaron: “Justin and I are talking about a Red Feather Ramble trip leaving from town Thursday afternoon, 09/25. Any interest in joining? I’ve got all the gear you might need.”

Of course, I said yes. That message turned into my first multi-day bike trip. I’ve been riding with Jaron and Justin for over a year now. They’ve shown me incredible trails and hidden corners of Colorado, helping me expand my map, both literally and metaphorically. Thanks to them, I’ve learned how far we can go when curiosity leads the way, and I’ve also learned what “Type 2 Fun” really means.

My only previous experience was this past summer, during the Swift Campout here in Boulder, around the solstice. Treehouse Cyclery, our local shop, hosted the event and lent me gear from their “bikepacking library” so I could take part. I had ridden the route before, but never with a fully loaded bike and in such heat. Back then, I was on a late-1980s Gary Fisher. This time, everything would be different: a new bike, more days, more distance.

We finally rolled out on Wednesday, the 24th, just after noon. Justin and I left Boulder, heading toward nearby Longmont, picked up Jaron at his work, and continued north to Fort Collins. The plan was to reach the Horsetooth Reservoir campground by nightfall, but to do it by crossing the Devil’s Backbone, a stretch of rocky singletrack that would deliver us straight to camp. Naturally, it turned into the trip’s hike-a-bike moment. Justin’s main goal was to have fun and not break Roger, his 1984 Stumpjumper. Jaron, who had dreamed up the whole trip, was also riding a 40-year-old Stumpjumper.

There’s something of those bikes’ spirit in this trip—the moment when we decided to leave the efficiency of pavement behind and head for the wild. To trade speed for experience, the city for open terrain. French anthropologist David Le Breton, in The Praise of Walking, reflects on the body, the senses, and the human experience of moving through the landscape. Though he writes about walking, much of what he says applies perfectly to bikepacking. Curiously, the thinkers he cites mostly wrote in the early 1980s—around the same time those two Stumpjumpers were built. Perhaps something in that era sparked the desire to explore less-traveled paths.

After a beautiful sunset across the Devil’s Backbone, we reached our first camp at Horsetooth. That night, Nick joined us, showing up with a broken spoke in his rear wheel but deciding to keep going anyway—it didn’t look too bad. Consensus quickly formed: Horsetooth isn’t an ideal camping spot, especially on a Wednesday. A noisy night, little charm. The experience would shape our decisions later in the trip.

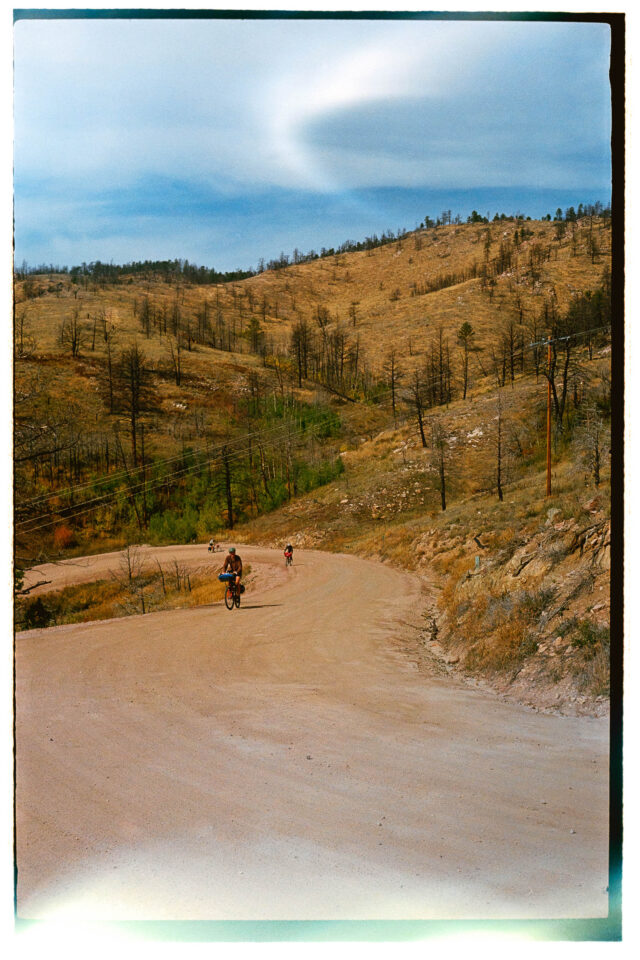

The next morning was frosty but bright. We packed up and headed for the mountains—now a team of four moving at a steady rhythm through the hills. I like to imagine us as a slow train in single file, calm but constant. Our last stop before the dirt roads began was the small Masonville Mercantile, an old gas-station-turned-store that’s been there since 1896. In 129 years, places like this have surely seen countless travelers like us—some maybe on similar 1980s bikes, others on foot, like Le Breton’s wanderers—but all sharing that same urge to step away, even briefly, from the social clock and the paved road. As Le Breton writes, “To move through the world is to suspend social time and rediscover one’s own rhythm.”

Traveling from the city to the countryside helps us find that rhythm again. To inhabit space through the senses, to form a more intimate relationship with the world. Moving slowly through these landscapes reveals layers of history, both human and natural. You can read that history on the cracked walls of old buildings, on the flanks of the hills, and in the burned forests with young trees slowly growing back, their yellow leaves glowing once more.

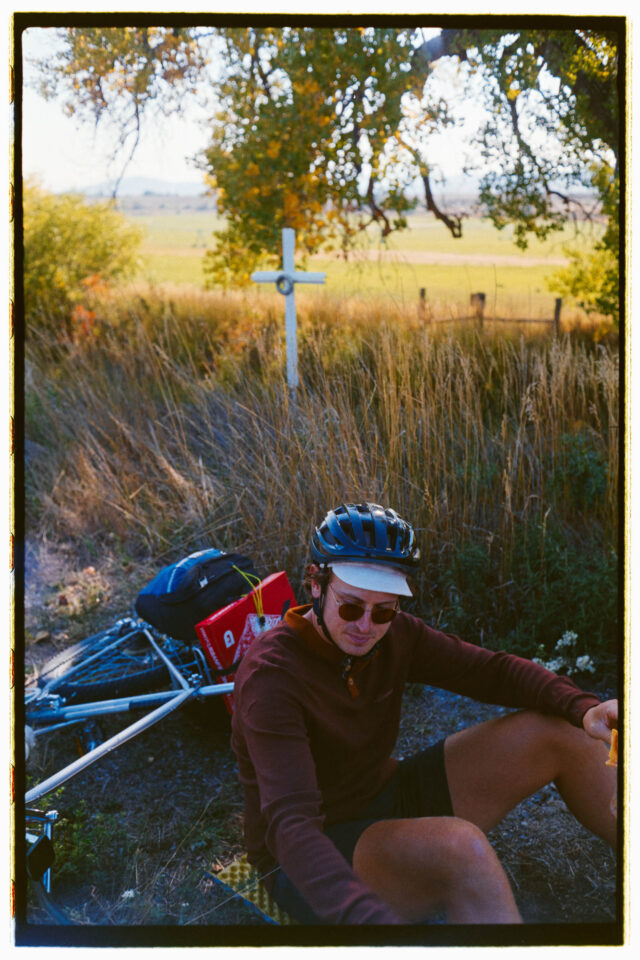

Our rhythm was easygoing. We stopped whenever we wanted—there were always snacks and good humor. It was my first trip like this; for them, it was routine. The atmosphere was familiar and full of laughter, though sometimes my English felt tired, so I listened more than I spoke. Le Breton quotes Töpffer: “When one sets out on a journey, it’s wise to pack, besides the backpack, a good supply of spirit, joy, courage, and good humor.” That courage and good humor defined our trip.

After a long climb up toward Peenock Pass, we were rewarded with a stunning descent. The landscape was brushed with reds and golds. The air was cool, the trail empty. It felt as if the whole route belonged to us. We stopped to take photos at every opportunity, the fatigue in our legs from a full day of climbing fading with every breathtaking view.

Le Breton often emphasizes the relationship between body and environment. Reading his words, I find echoes of what I felt out there on the bike:

“Walking reduces the immensity of the world to the scale of the body. One gives oneself to the resistance of one’s own muscles, to the wisdom of choosing the path that best suits the journey—whether it leads to getting lost, if wandering is one’s philosophy, or to arriving swiftly if one simply seeks to move from one point to another. Like all human endeavors, even thinking, walking is a bodily act, but more than any other it involves breath, fatigue, willpower, courage in the face of hardship and uncertainty, hunger and thirst when no water or shelter is near. It is the body, not the clock, that measures the journey.”

To move through the landscape this way connects us not only to the land and its inhabitants, but to ourselves—to our own bodies and rhythms. We face fatigue and discomfort, both physical and mental. We strip away the pace of daily life and stand body to body with the world. Time slows to the measure of our breath and desire. The only rule is to stay ahead of sunset. The clock becomes cosmic—of nature, of the body—not of culture and its meticulous divisions of time.

Though this is a bike trip, my approach was always photographic. I brought four rolls of film: one half-used from a New York trip, three fresh for the days ahead. A little over a hundred frames to capture it all. One camera, one lens. The camera is older than Justin and Jaron’s bikes—late 1950s, a simple mechanical Canon with a 35mm lens from the same era. It feels right for this kind of journey: simple, compact, fully manual.

We each started from our own homes, which I found meaningful when thinking about how we relate to places. No support vehicles, no shortcuts. Le Breton also writes that walking is a symbolic act of resistance. Traveling through places—urban or wild—means reclaiming them, making them your own, while letting them also claim a part of you. It’s a reciprocal relationship. We move quietly, find presence in the here and now, and subvert the order imposed by maps and urban plans by drawing our own lines across the land.

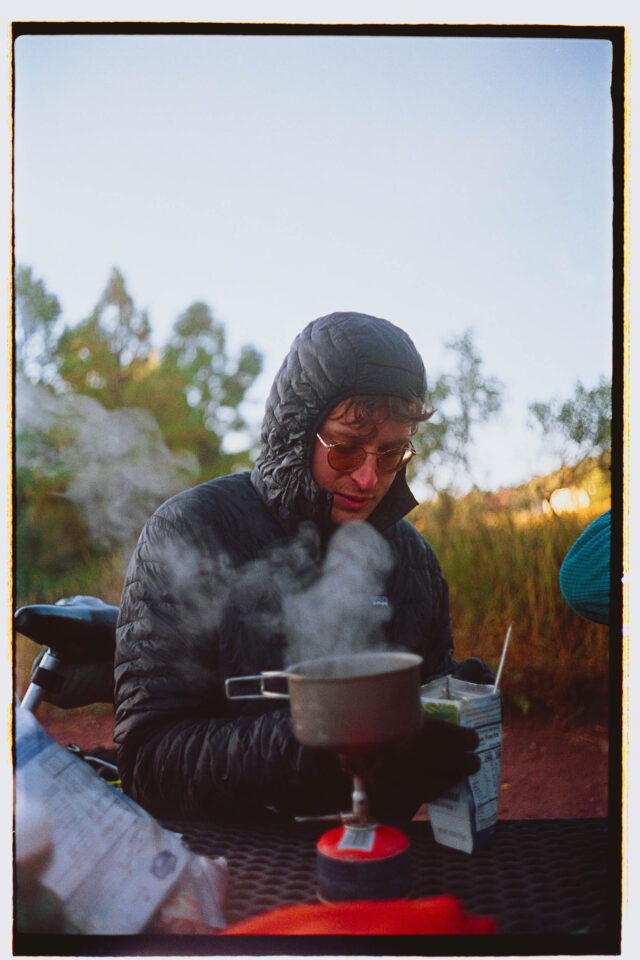

Before sunset, we found a quiet spot to camp—much more peaceful than the last, though colder too. We slept well and continued up the mountain. By then, the feeling of rambling had taken over: wandering, forgetting time, and surrendering to the landscape. The days were perfect—bright and crisp—and the hills around us glowed in reds and yellows. We came in the right season.

The third day ended at Roosevelt National Forest, our final and best campsite. We finally made a fire and warmed our bodies as the sun went down. It had been an easygoing trip overall—steady but relaxed. We didn’t push too hard, though there were moments of effort and quiet challenge. We planned our fourth day, uncertain about routes but sure we’d visit the lookout tower, the highest point of the journey.

In the end, we decided to return by the same route, exploring new side roads along the way. Here again, Le Breton’s idea appears—the need to relearn the territory, to experience it not as empty space to be conquered but as a living body to cross with respect and wonder. Guy Debord captured it perfectly:

“One or more people who surrender to drifting give up, for a time, their usual motivations for moving or acting in their relations, work, or leisure, allowing themselves instead to be drawn by the terrain and by the encounters it brings.”

After some debate about whether to camp again, we decided to end the trip on the fourth day and ride straight home. After three slow, meandering days immersed in the landscape, we returned—almost reluctantly—to the rhythm of the social clock. The same urgency that made us leave home to explore also made us long to return. The hills faded into dusk, the glowing trees disappeared in the dark, and the new roads turned back into familiar ones.

The route itself wasn’t what mattered most, nor the record of it. What mattered was the experience—the encounter with the territory, the act of drifting through space, of trusting the body to lead the way. A body flooded with smells, colors, temperatures, and light—the true engine that carries us forward.

Presented here, the trip might look like just a weekend trip with friends, but it was more than that. It was an act of quiet rebellion against imposed time, a small physical wager between us and our bicycles—but above all, it was a reconnection with the land and with ourselves, through every uphill pedal stroke and every night sleeping out under the stars.

The 40-year-old Stumpjumpers held up beautifully, their riders too—it’s in their spirit. Nick finished the trip despite his broken spoke. I was surprised by how comfortable I felt the whole way. Different languages, different cultures, but many shared points. Friendship grows stronger out there. I took my photos and rediscovered myself in the landscape, and now I can’t help but wonder if David Le Breton might enjoy a bike ride.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.